In Search of Parallel Worlds: A Portrait of Ilija Šoškić

Ilija Šoškić, born in 1935 in present-day Kosovo (then part of Yugoslavia), and raised in present-day Montenegro, became the most known representative of the Montenegrin neo-avant-garde, although the artist would never call himself that. Rejecting any nationalist aspirations of the post-Yugoslav states, he sees himself instead as a nomad or a pilgrim(1)—somebody constantly on the road. Nevertheless, he has returned on several occasions to Montenegro and currently is based in neighboring Croatia.

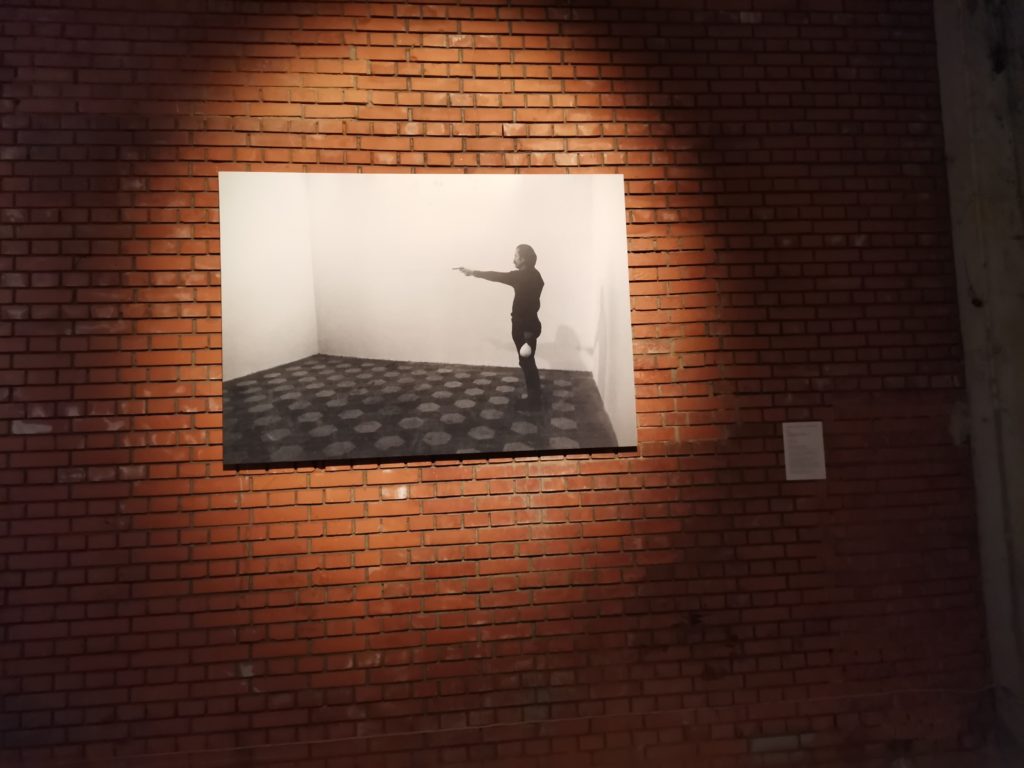

Exhibition view, “Microcosm of Ilija Šoškić” at the Kolector art venue, curated by Nela Gligorović, Podgorica, June 2021, Photo: Karolina Majewska-Güde

Šoškić’s actions, installations, and objects have been exhibited since the 1970s at many group and individual exhibitions, mainly in Italy (in the 1970s) and in the former Yugoslavia.(2) In recent years several articles and interviews have been published by regional critics and art historians of different generations, such as Ješa Denegri and Marina Gržinić, exploring all different aspects of the artist’s work.(3) Particular interest in Šoškić’s practice also came from Montenegro, his place (country) of origin. In 2011 the artist represented the country at the Venice Biennale,(4) and recently he has been granted a retrospective exhibition, The Microcosm of Ilia Šoškić, organized by the Department of Culture of Podgorica and accompanied by a bilingual catalog.(5) The recent exhibition in Podgorica has been preceded by a large retrospective in Serbia, Action Forms, organized jointly by the Museums of Contemporary Art in Belgrade and Novi Sad.(6) All these exhibitions offered various versions of the multi-threaded history of the artist’s work.

I met with the artist at the occasion of the recent retrospective exhibition The Microcosm of Ilia Šoškić, at the Kolektor art venue in Podgorica (May–June 2021) to talk with him about his work and ideas. It was, on the one hand, an opportunity to revisit his oeuvre and look at the concepts and narratives that have been spun around his practice in recent years. On the other hand, it was an opportunity to initiate a conversation inspired by the artist’s more recent works and concerns. My conversation with Šoškić and art historian Dragica Čakić, his archivist and partner of 30 years, focused on so far less-discussed and quite specific questions: the meaning of documentation in Šoškić’s practice; his gendered aesthetics; how he perceives the issue of collaboration; and how he understands the role and the position of the artist—today, in the post-Yugoslav space and in Montenegro in particular.(7)

This article, which partially summarizes our conversation, addresses these questions while aiming to shed light on Šoškić’s practice and the path that led him from a militant anarchist practice to radical ecology. In his practice, Šoškić redefines what socially engaged art may mean and how it can operate. Against the image of the artist as a unique and unfitting individual, which is revealed from the existing literature on his practice (“it is not that Šoškić does not fit into the art system—rather, he neither wants nor attempts to fit in anywhere”).(8) I want to reflect rather on the distinctiveness of Šoškić’s work in the face of contemporary eco-political concerns. Thus, I propose to look at Šoškić’s work entangled in the notions of so-called nature, energy, life, and liveness from an eco-posthumanist perspective emphasizing the process in which he reconsiders the actual and potential role that art can play in facilitating and fostering alternative ways of being in the world.

Maximum Energy in Minimum Time

Šoškić’s best-known work—and the one that introduced his practice to an international audience after 1989—is a photograph Milk and Silk, also known by the catchier title Maximum Energy in Minimum Time. A black and white photograph depicts a man holding a bottle of milk in one hand and a revolver aimed at something or somebody in the other. He stands in the right corner of the frame aiming his weapon at the edge of the picture as if opening it violently. The milk is an attribute of a shaman, but he looks rather militant in a Red Army uniform: a revolutionary who believes that “the point of art is rebellion and subversion”(9) and that the avant-garde is underway to change the world. The photograph is reproduced in the catalog of the exhibition The Body and the East, one of the first collective surveys of the performance and action art scenes in former socialist Europe from the 1960s to the late 90s curated by Zdenka Badovinac in 1998. It is also an indication of the artist’s interest in the “smart aesthetics”(10) of photographic documentation, which not only conveys the original idea of the artistic action but also expands it.

Exhibition view, “Microcosm of Ilija Šoškić” at the Kolector art venue, curated by Nela Gligorović, Podgorica, June 2021, Photo: Karolina Majewska-Güde

The photograph was taken during the performance, realized by Šoškić in January 1975 at Fabio Sargentin’s Gallery L’Attico in Rome within the framework of the “24 Hours a Day Project”: a series of actions continuously performed during seven days and nights by several neo-avant-garde artists including, in addition to Šoškić, Tano Festa, Jannis Kunnelis, Emilio Prini, Mimmo Germana, Alighiero Boetti, Vettor Pisani, Eliseo Mattiacci, Sandro Chia, Luigi Ontani, Francesco Clemente, Luca Patella, and Gino De Dominicis. The action shown in the photograph was preceded by three stages, or, as Šoškić has it, “live-images,” “tableaux vivants,” or “transformas”—performed for both the primary audience and for the camera. The first tableau, “Silk Cushion (Conversation),” consists of the artist sitting on a red silk cushion and talking to the audience. In Šoškić’s words, the artist performed a “verbal sculpture” that consisted of a polemical dialogue with a member of the audience, a journalist from the Vatican newspaper L’Osservatore Romano. During the second tableau, “Knife Stuck into the Wall (Controversy)” the artist placed a knife in the geometric center of the gallery wall. The third tableau, “Arm-wrestling (Demystification),” was arranged as a wrestling competition between Šoškić and the American painter, John Ranter, performed on a chest table. The fourth tableau, “Firing a Bullet from a Revolver into the Gallery Wall (Non-Act),” resulted in the mentioned photograph that became the artist’s trademark and a kind of tool for the institutional distribution of his practice.

The image of Šoškić firing a gun at one of the walls of Galleria L’Attico can be seen as an instant introduction to his early practice. On the one hand, according to Montenegrin art historian Petar Čuković, the image captures all dominant and connected streams of Šoškić’s work, defined by Čuković as a critique of Western values (such as heroism, etc.), the anarcho-libertarian critique of the art system, and paramilitary actions aimed against capitalist (dis)order.(11) Moreover, it problematizes the concept of energy relating to the Spinozian undercurrent of Šoškić’s practice, his interest in a materialist conception of life (zoe), and liveness understood as the expansion of energies. This being said, the photograph fails to represent the complexity of the performative event that took place in the L’Attico gallery. It says almost nothing about the dramaturgy of the event and its reception. For this reason, however, this photo is very representative of Šoškić’s practice. It introduces the anti-documentary impulse present in Šoškić’s work, who uses the camera very sparingly, creating laconic images of complex choreographies.(12) It also speaks about certain absences related to the fact that Šoškić often makes artistic works not for an exhibition or for distribution within the institutionalized art world but just for his own experience. He argues that art helps him “to work on his own obstacles,” which should be understood in a broader context of his approach of “overcoming all possible obstacles and limitation—political and cultural—in the given context.”(13) This authorial narrative is a version of a neo-avant-garde story about merging art and life, which aims to reconfigure the relationship between artistic practice and non-art. It is also a modification of this narrative by placing life at the center of the story. Existing interpretations of Šoškić’s practice more or less follow this authorial tendency and aim to reconstruct Šoškić’s life and work continuum.

Exhibition view, “Microcosm of Ilija Šoškić” at the Kolector art venue, curated by Nela Gligorović, Podgorica, June 2021, Photo: Karolina Majewska-Güde

Genealogies of Šoškić’s Art

Since the early 1970s, Šoškić has worked and exhibited transnationally, due to the fact that he emigrated and worked between several countries. He took part in student protests at the Belgrade Art Academy in 1968, and after the protests collapsed in 1969, he went to Paris to help the revolution. On his way, he stayed in Bologna and later in Rome, where he worked in the circles of the Italian new left and became friends with Giangiacomo Feltrinelli, Antonio Negri, Oreste Scalzone, and others “whose intellectual activity gave positive affirmation to a life worthy of principles beyond profit and greed.”(14) In 1970 he enrolled at the Bologna Academy of Fine Arts. His artistic practice developed in relation to both the circles of the radical Left in Italy—in Bologna (Gallery GAP) and from 1972 on in Rome (Galley L’Attico) —and to the New Art Practice in Belgrade, where he exhibited at the Students’ Cultural Centre.

One way to tell a story about Šoškić’s artistic practice is to see his work as closely related to his left-wing political activism, his life as an uncompromising critique of political power, and him as someone trying to take a certain autonomous position within and through the realm of art. Keeping in touch with his socialist country of origin, always engaged in left-wing anarchist politics and the critique of social injustice: Šoškić became a professional revolutionary. In her essay in The Body and the East catalogue, Bojana Pejić defines his work through the notion of the Anarchist Body.(15) This idealistic or even utopian attitude led him to leave Italy in 1981, where he refused to enter the commercialized art world. Disillusionment with the developments in art embodied by the trans-avant-garde made him return to the Yugoslav region and partly to Greece. Yet, in 1995 he returned to Rome at the invitation of his friend Jannis Kounellis, where he stayed until 2017.

Despite his nomadic life, he remained in close contact with his country. This was confirmed by the invitation to represent Montenegro at the Venice Biennale in 2011 (together with an artist of the younger generation, Natalia Vujoševic, and in collaboration with Marina Abramović’s Community Center Obod). Already a couple of years earlier in 1986 at the Forum Gallery in Nikšić (repeated in 2013 in Cetinje), Šoškić’s installation Mourning and Drought intended “to express mathematically an axiom that would evoke Montenegrin traditional dramaturgy (mourning) and scarcity (drought),” referring to local material practices. He aimed “to find one of those old stone barriers that peasants in Montenegro built to prevent landslides in the same way that beavers do, and then to transfer this wall into a gallery.”(16) The picture of this installation is on the cover of the catalog of the recent Podgorica retrospective as a way to demonstrate Šoškić’s special bond with the country, which was certainly one of the goals of the exhibition. The artist himself often emphasizes the origin of his artistic practice as a result of regional artistic influences and personal crises experienced in the early ’60s, prior to which he was studying sculpture at a Montenegrin art college in Herceg Novi(17): “This time, out of desperation, I cut the pieces of wood, just to keep me busy, do something. From 1962 to 1966 my ‘carpentry’ was born, which later began to be more and more conceptualized. I thought of ‘poverty,’ of which I knew through Grotowski’s ‘poor theater,’ (18) and the ‘things’ of art that took place in the 1960s (especially in Yugoslav cinema, known as ‘the black wave’).” (19)

The sculptural lineage can be traced in several of the artist’s performative works realized in the 1970s. In the camera performance, Sisyphus (1975, Tubingen), for example, we can see Šoškić in the quarry as he struggles to move a large piece of stone, touching it and helplessly pushing without being able to alter either the position or the shape of the stone. However, every artistic practice has multiple genealogies. In the case of Šoškić’s work, the most spectacular narrative is certainly the one that connects his performative gestural work with his career as an Olympic athlete. In the early ‘60s, Šoškić joined Red Star Slavonia, the senior national team of Yugoslavia, and in 1962 he set a Montenegrin record (still held) in hammer-throw. In 1970 he also joined the Virtus Bologna Club to continue his passion for sports. At the time, however, he was already describing his participation in a hammer-throwing competition in terms of artistic action—as a tautological performance that included an informed audience made up of artist friends: Corrado Costa and Luigi Ontani.(20)

Bojana Pejić has argued that in his work Šoškić merely uses and comments on the energy of the human body, which is “a power which is in our culture either suppressed, wasted, or even remained unfound.”(21) She continues that the artist “tries to re-create this energy in himself in the course of the performance and therefore each of his performances implies usually long periods of body’s quiescence. The action in a performance piece is reduced either to one simple artistic gesture, a slow movement of arms, or by an abrupt act.” (22) This description seems to be adequate also to the sporting feat, and it also aptly describes sports photography.

Several of Šoškić’s camera performances refer directly to the concept of training the body and a sport-related vocabulary. In Physical Exercise No. 9: Absence as Presence (1976, Lucio Amelio Gallery, Naples) the artist follows the army’s exercise routine. In addition, Šoškić decided at some point to maintain a sporty image and not to be represented visually as an “artist.” (“My image is already by then no longer aesthetic but sporty”).(23) But the iconography produced by Šoškić is not only full of muscles, gymnastics, and stones, which the artist heroically carries through the city—as in the performance A Rock on the Shoulder, realized at the art fair in Basel 1974 (Galerie GAP, Rome)—but also with weapons, Red Army uniforms, mustaches, and motorcycles, some of which have been the object of the critique. In the camera action Hero (1976, Ostia), for example, Šoškić marches senselessly along the coast in a Red Army uniform. Likewise, his Sisyphus, which demonstrated failure, it is not a glorification, but criticism of male heroism. It is more of a “ruptured machoism,” a kind of drag-macho aesthetic that is now and then accompanied by painted nails or pink ribbons, as in his camera performance Pilgrimage (Hero’s Walk) (1975, Hohenzollern Castle, Tubingen). Nonetheless, Šoškić uses metaphorical military language in his self-narrative, that reveals a certain fascination for stereotypical masculinity: “When it comes to the moment of the making of an actual piece, action—then I am freeing myself from what I have learned. I implement an idea directly, without thinking—like a bullet from a gun.”(24)

Exhibition view, “Microcosm of Ilija Šoškić” at the Kolector art venue, curated by Nela Gligorović, Podgorica, June 2021, Photo: Karolina Majewska-Güde

In this context, it is worth mentioning Šoškić’s interest in radical feminism and his collaboration (1976–79) with an anarcho-feminist group co-organized by the Italian actress Nicoletta Machiavelli. Šoškić explains that what attracted him to feminist activists was not so much feminist postulates but the fact that “they were very radical and revolutionary.”(25) It is also important to mention in this context his close collaboration with his partner and archivist Dragica Čakić and with his daughter Stefanija Šoškić, with whom he realized a series of performances. When asked about his working relationship and collaboration with Dragica Čakić, Šoškić speaks about the concept of connectedness, which goes beyond stereotypical gender roles and hierarchies that are inscribed in the artist-archivist relationship. He also strongly associates the question of emancipation with the idea of thinking beyond binarism.(26) Dragica Čakić even goes so far as to describe Šoškić as an artist of a feminist orientation, emphasizing that he is “an individual artist and was neither interested in a particular system nor in belonging to the group.” Šoškić resolutely opposes any suggestions of contextualizing his art in terms of collaboration or influence in relation to Belgrade or Bologna artistic circles. He insists that what brought him together with fellow artists was never a particular way of making art or working together, but rather his Left-wing beliefs.

“Star bene”: Šoškić’s Radical Ecology

Despite Šoškić’s self-historicization—which emphasizes artistic autonomy and independence—“dependency” and “collaboration” are key terms for approaching his works dealing with nature, which he conceives as a zone removed from any social conventions or institutional framing(27) but not as radically separated from culture. Šoškić avoids the depoliticization of nature, and does not ascribe to the ecological discourse—where “nature ends up objectified as an ontology divorced from social, political and technological processes.”(28)

One aspect of his preoccupation with the redefinition of the human relationship to so-called nature relates to his early performative works from the 1970s, which he realized together with non-human others. From the zoocentric perspective, Šoškić can be accused of an instrumental use of animals in his art—of employing them as peculiar “signs” and not as sentient subjects. The best example of this practice is a performance with a living python (Coexistence, IV April Meetings, 1975, SKC Belgrade) that was brought to a gallery space from the Belgrade Zoo and which the artist “accompanied” for several hours. Although this was a risky and daring action, today we think about it, above all, in terms of animal cruelty and human arrogance. At the same time, the title of the work suggests the artist’s intention of getting connected with and establishing a relationship with the animal. In his earlier work Icarus (Sparrow on the Shoulder), Šoškić wanted to become “part of a flight”(29) but he also problematized the idea of human ignorance and megalomania: “it is my attempt at being Icarus, to be also a part of that flight myself. The myth tells the story about Icarus as a typological sign of the human mentality; obsession, megalomania, even also bravery.”(30)

The presence of the companion species—a snake and a sparrow—evokes a posthumanist ontology of connectivity, but at the same time, we can say that Šoškić’s practice is far from the contemporary concepts of trans-species solidarity. While it represents a departure from the focus on the individual subject, it does not establish a community, but rather a constellation that is still based on the symbolic meaning of non-human others. Nevertheless, his work has been critical of the hierarchical relationship between “man and nature.” A year before working with the python, during the same event of the April Meeting at SKC in Belgrade, Šoškić realized a camera performance Sewing the Ficus, in which he sewed leaves of the ficus plant, indicating that the so-called cultivation of nature implies a violent relationship with the world around us.

If in his earlier works non-human others appeared mainly as symbols and objects of his interaction, today the artist makes collaborative works together with non-human persons and elements of the environment, establishing relations between them that aim to exclude violence and promote a symbiotic view of life. For example, in his works from the series The Dream of the Pagan Priest (1977–1980 actions, installations), Šoškić takes various positions and exercises in the water and on the beach with animal horns, proposing vitalist body art rituals for reconnecting with the world.

In 1980 the artist also moved towards actual politics and participated in launching the Green Party in Italy. At the same time, Šoškić’s artistic projects are hard to reconcile with the eco-activist paradigms of “ecovention”(31) or “restorationist eco-aesthetics,” which refer to “art that attempts to repair damaged habitats or to revive degraded ecosystems.”(32) His ecologically informed art is more intimate and contemplational. It deals with his physical presence in the material world or organic and not organic nature. Šoškić’s works gravitate towards recreating an affective connection between himself and the environment in which he is present through self-designed ritual acts. He also identifies and makes visible zones of contact between different living organisms. As Marina Gržinić put it, Šoškić is “interested in Life, not as in getting by—but as in act/deed/event.”(33) In his early performances, he studies life through the study of energy flows in his own body. In more recent works he creates laboratories of life or observation points from which he can experience the common state of vitality.

Such a work is the video-essay Zygote (2011), which consists of five parts shot at different locations in Montenegro: “The Hawk,” with a mountain peak in the background; “The Serpent,” in front of a wooden hat; “The Bleak” (an endemic fish found in Lake Skadar) on a boat. In the fourth image, “The Sparking,” the artist sits on a stone in the middle of a riverbed, with his back to the camera, while in the final image, Šoškić is located in a white cube, perhaps a gallery space, as he methodically and slowly peels an apple.

Petar Ćuković has interpreted this work in terms of visualizing a Nietzschean vitalism and points out to the proliferation of Nietzschean themes such as Zarathustra’s eagle-serpent pairing.(34) He also referred to Gaston Bachelard’s Water and Dreams, in which the French author develops his idea about material imagination, as a reference point for Šoškić’s statements about water made in the film.(35) But if we look at this work from the contemporary posthumanist perspective, we can argue that Šoškić became a practitioner of trans-species solidarity, that he exercises here thinking-with, storytelling, or wording (36) together with non-human others. In one of his interviews, he explicitly comments on this evolution in his practice: “We all saw that the capitalist-bourgeois system could not change, that even when overthrown, it still had the power to quickly regenerate itself. We realized that one should explore new worlds, parallel worlds.”(37)

Šoškić advocates today through his practice ethical care for the shared world—“assuming maximum responsibility and commitment.”(38) It is important to ask: what is the ability of art to cultivate responsibility for the world? While working with animals and exploring parallel worlds of terrestrial- and hydro-commons, Šoškić remains very much attached to the political and social reality of today, arguing that an artist shouldn’t distance himself too much from it, that she has to keep track and be aware of what is going on in the world. At the same time, an artist, according to Šoškić, “should try not to be touched by political turbulences and dynamic balances of power” in order not to be instrumentalized by political and commercial players.(39) This approach does not rule out being disillusioned, and it even proposes a certain ethics of failure (“If you accept the system you will get rich, if you disagree you are on the verge, hanging out like me.”)(40) The question remains open as to how critical Šoškić’s vision of parallel worlds is. And to what extent is his transition from an anti-capitalist revolutionary into a practitioner of environmental storytelling a question of escaping into the vitalistic imaginary world in which he can maintain the secure position of the artist-philosopher? Taking seriously these skepticisms does not prevent us from observing that Šoškić successfully occupies an ambivalent position of attachment and detachment, a position from which he can express himself with commitment.

FOOTNOTES

- I refer to the title of Šoškić’s performance Pilgrimage (Hero’s Walk), from a 1975 performance realized at the Hohenzollern Castle, in Tubingen, Germany. [back]

- Šoškić exhibitions are listed in Biography prepared by Dragica Čakić in Ilija Šoškić: Action Forms, [Ilija Šoškić: Akcione Forme], ed. Zoran Erić, Nebojša Milenković (Novi Sad and Belgrade: Museum of Contemporary Art Vojvodina, Novi Sad, and Museum of Contemporary Art, Belgrade, October 13 – December 24, 2018), exhibition catalog, p. 203. The publication is available online: https://www.academia.edu/39967555/Ilija_%C5%A0O%C5%A0KI%C4%86_Akcione_Forme_Action_Forms _Exhibition_catalog_MSUb_MOCAB_MSUV_MOCAV_Belgrade_Novi_Sad_2018. [back]

- See Bibliography prepared by Dragica Čakić in Erić and Milenković, Ilija Šoškić: Action Forms, pp. 208–212. [back]

- See footnote 2. [back]

- Mikrokozmi Ilije Šoškića [Microcosm of Ilija Šoškić] ed. Dragica Čakić and Nela Gligorović (Podgorica: Secretarioat za Kulturu i Sport Glavnog Grada—Podgorica, Maj 2021), exhibition catalog. [back]

- Erić and Milenković, Ilija Šoškić: Action Forms. Milenković’s text “Ilija Šoškić—An Artist of Living Images” not only captures Šoškić’s work in a comprehensive and interesting way but also provides detailed biographical and bibliographic information. [back]

- An Interview with Ilija Šoškić and Dragica Čakić was conducted in Podgorica on June 4, 2021. This interview would not have been possible without the generous help of Irena Lagator Pejović (https://www.irenalagator.net/) a Podgorica-based artist and scholar who not only helped me organize the meeting but also acted as a translator. All quotes in the text that are not referenced in the footnotes are from this interview. [back]

- Milenković concludes his essay in this tone: “His performances, actions, installations, sculptures, ambiances, concepts, drawings, sketches, objects, events, video and photo essays are all part of a unique authorial procedure whereby Šoškić himself becomes the subject and material of his own art, approximating the situation that Beuys had proclaimed in the early 1970s: To turn oneself into an event—to be a living sculpture. A nomad in life as much as in art, simultaneously belonging to and acting in different cultures (European, Italian, Yugoslav, Montenegrin, Croatian, Serbian), Ilija Šoškić has managed to remain what he always was: unfitting. Consistent. Radical. His own.” Erić and Milenković, Ilija Šoškić: Action Forms, p. 136. [back]

- From the letter to Jannis Kounellis published in Erić and Milenković, Ilija Šoškić: Action Forms, p. 112. [back]

- Author’s interview with the artist, June 4, 2021 (Podgorica). [back]

- Petar Čuković, “Zygote”, in The Fridge Factory and Clear Waters: Marina Abramović Community Center Obod Presents: Ilija Šoškić, Natalija Vujoševic (Podgorica: Contemporary Art Centre, 2011), exhibition catalog, pp. 78–89, p. 81. [back]

- Nebojša Milenković writes about this aspect of Šoškić’s work that “Upon realization, his actions and gestures were by and large not properly documented, but continued to last only as mental facts.” “Ilija Šoškić—An Artist of Living Images” in Erić and Milenković, Ilija Šoškić: Action Forms, pp. 123–139, p. 126. [back]

- Author’s interview with the artist, June 4, 2021 (Podgorica). [back]

- Milenković, “Ilija Šoškić,” in Erić and Milenković, Ilija Šoškić, p. 128. [back]

- Bojana Pejić, “Body-Based Art: Serbia and Montenegro,” in Body and The East: From the 1960s to the Present, ed. Zdenka Badovinac (Ljubljana: Museum of Modern Art, 7 July–27 September 1998), exhibition catalog, pp. 72–80, p. 77. [back]

- Milenković, “Ilija Šoškić,” p. 134. [back]

- The School of Fine Arts at Herceg Novi (1946–1967) was a very influential institution for two generations of local artists who otherwise educated themselves abroad. More information at http://www.webport.cloud/montenegro-en/art-school-cetinje-herceg-novi/?lang=en [back]

- The 1964 Jerzy Grotowski’s article “Towards a Poor Theater,” was published in 1965 in the magazine Scena of Novi Sad. [back]

- Artist’s statement made in 2019 was published on Gandy Gallery’s website. See: https://www.gandy-gallery.com/exhibitions/bratislava/2019-ilija-soskic-exhibition/ [back]

- Milenković, “Ilija Šoškić,” p. 143. [back]

- Pejić, “Body-Based Art,” p. 77. [back]

- Ibid. [back]

- Artist’s statement in Erić and Milenković, Ilija Šoškić, p. 118. [back]

- Author’s interview with the artist, June 4, 2021 (Podgorica). [back]

- Ibid. [back]

- Ibid. [back]

- Statement made in the letter to Jannis Kounellis, in Erić and Milenković, Ilija Šoškić, p. 113. [back]

- T. J. Demos, “The Politics of Sustainability: Contemporary Art and Ecology,” in Radical Nature: Art and Architecture for a Changing Planet 1969–2009, ed. F. Manacorda, (London: Barbican Art Gallery, 2009), p. 20. http://www.environmentandsociety.org/sites/default/files/key_docs/Demos_Art_and_Ecology.pdf. [back]

- Artist’s statement in Erić and Milenković, Ilija Šoškić, p. 28. [back]

- Ibid. [back]

- See Sue Spaid, Ecovention: Current Art to Transform Ecologies (Cincinnati: Contemporary Arts Center, 2002). [back]

- Demos, p. 19. [back]

- Marina Gržinić, “Ilija Šoškić: Ostati živ,” Art centrala—Časopis za savremenu umjetnost 5 (June 2011): pp. 14–17. Quoted in Milenković, “Ilija Šoškić,” in Erić and Milenković, Ilija Šoškić, p. 136. [back]

- Čuković, Zygote, p. 89. [back]

- Ibid. [back]

- Donna Haraway, Staying with the Trouble: Making Kin in the Chthulucene (Durham: Duke University Press, 2016). [back]

- Quoted in Milenković, “Ilija Šoškić,” in Erić and Milenković, Ilija Šoškić, p. 129. [back]

- Milenković, “Ilija Šoškić,” in Erić and Milenković, Ilija Šoškić, p. 129. [back]

- Author’s interview with the artist, June 4, 2021 (Podgorica). [back]

- Ibid. [back]