Focus Issue on Serbian Art in the 2000s

I was invited by ARTMargins editorial team to write a text and edit a special issue about the art scene that has developed in the past ten years in Serbia. For those readers who are not familiar with the local, political, artistic, and cultural context of Serbian art, I will first point out the historical circumstances that determined the development of the scene, and then I will sketch the theoretical framework that is relevant for the understanding and interpretation of contemporary Serbian art. I will also write about the institutional context in which this art is produced and, finally, I would like to point out concrete authors whose work is relevant for the local art scene.

Historical context

The Serbian art scene of the last ten years developed in a specific social and political context: the fall of the Berlin wall in 1989; the collapse of the Eastern bloc; the fall of the communist political and economic system; the disintegration of former Yugoslavia; the violent civil wars of the 1990s; the international isolation of the country in the same decade; and finally, after 2000, the process of social democratization and the neo-liberal transition. These circumstances were not characteristic for the rest of the Eastern European countries, at least not in such a dramatic way, and they left a lasting influence on local artistic and cultural practices in Serbia.

A few historical events should be pointed out in particular: in 1989, Slobodan Miloševi? became the country’s leader, and he stayed in that position until 2000. It was a period when the “democratic” parliamentary system was introduced, at least on paper. But in reality, this decade was remembered as the period of Miloševi?’s “soft” dictatorship, the disintegration of former Yugoslavia, and bloody civil wars between 1991 and 1995 in Slovenia, Bosnia, Herzegovina, and Croatia. This was also the period of the international isolation of the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia, (consisting of Serbia and Montenegro, after the split of other former Yugoslav republics), because of their involvement in the war. At the end of the decade, the war conflict also occurred in Kosovo, a former southern Serbian province that provoked a military intervention of the NATO pact in 1999.

In 2000, Miloševi?’s quasi-totalitarian regime was overthrown by peaceful, democratic demonstrations when oppositional, democratic parties formed a new, pro-European government. Since then Serbia has started a process of neo-liberal transition that has included radical changes made to its foreign policy that have moved the country from nationalistic self-isolation to the politics of European integration (Serbia officially applied for the EU membership in December, 2009).After the 2006 referendum in Montenegro, theFederal Republic of Yugoslavia disintegrated and Serbia and Montenegro became independent states. In 2003 the first democratic prime minister of Serbia, Zoran ?in?i?, was assassinated, and in 2008 the former autonomous province of Kosovo declared independence from Serbia. This is an issue that is still not resolved (until now, 69 UN members have recognized Kosovo’s independence).

The year 2000 can be considered crucial both for Serbian society and for the local art scene (the “democratic revolution” and the overthrow of Milosevi?’s regime mark a shift from the nationalistic 90s to the neo-liberal, transitional 2000s). The importance of these changes is also indicated by the critical formulas that are used for the interpretation of these decades: “art in a closed society” is a phrase commonly used for to explain the art scene of the 1990s, while “art in an age of globalism” is used for the interpretation of art and culture in the transitional 2000s.

One critic, Dejan Sretenovi?, coined the phrase “art in a closed society.” According to him, the 1990s in Serbia cannot be interpreted in a context of Fredric Jameson’s thesis concerning postmodernism as the “cultural logic of late capitalism”; nor can they be interpreted in the context of post-communist transition, where by the communist model of economic production was replaced by the neo-liberal economic model (postmodernism in consumer society did not exist in Serbia at that time). In fact, Yugoslavia stood apart from all global streams and process-art that emerged inside the society, which had been marked by wars; a general economic crisis; the destruction of social values; aggressive nationalism, and international isolation.Dejan Sretenovi?, „Umetnost u zatvorenom društvu“, Art in Yugoslavia 1992-1995, Fond za otvoreno društvo-Centar za savremenu umetnost, Belgrade, 1996.

On the other hand, “art in an age of globalism” is a phrase commonly used for the interpretation of art after 2000. Critic and art theoretician Miško Šuvakovi? understands this notion to mean that art that is produced inside a “planetary” process of networking on a social, political, economic, cultural and artistic level.Miško Šuvakovi?, „Umetnost u epohi globalizma“, group of authors, Istorija umetnosti u Srbiji, XX vek. I: radikalne umetni?ke prakse 1913-2008, Orion Art, Belgarde, 2010.

Theoretical context

The next problem when it comes to Serbian art in the 2000s is the analysis of the relationship between the local art scene and international artistic practices, i.e. the art of our time in general. Art practices in an age of global networking often transcend local frameworks and the category of “national” specifics has lost its relevance for the interpretation and valorization of art. At the same time, the main characteristic of art in both the global and local framework is the absence of any mainstream, much less dominant style, school, or movement (these are all categories characteristic of the modernism).Contemporary art, rather, emerges in an epoch of general artistic “immenseness.”

According to the art historian and critic, Ješa Denegri, inside the contemporary global artistic situation, the canonized methodological approaches of traditional art history are no longer adequate for understanding actual artistic practices; what is necessary, according to Denegri, are approaches that are, “based on interdisciplinary and inter-textual discussions that are used for reading and interpreting the aspects of contemporary art as cultural phenomena typical for reality [sic!] of contemporary mass consumerism and media society.”Jesa Denegri, “Symptoms of the Serbian Art Scene After the Year 2000”, Remont Art Files 01, Belgrade, 2009, 10.

Among the numerous theoretical theses that could be applied to understanding Serbian art in the 2000s are the following: Nicolas Bourriaud’s “relational art,” an art practice that uses inter-subjectivity as its basic artistic “material,” i.e. art that is no more interested in the artistic object but rather in social relations and in communication; Boris Groys’ take on art in the age of bio-politics – contemporary life is transformed under the influence of technology to the extent that it is impossible to make a clear distinction between organic and inorganic, natural and artificial. While classical art as an autonomous, artificial form tends to reproduce the “reality” of everyday life, contemporary art is a practice of documentation of the differences between live and artificial. Then there is Miško Suvakovi?’s suggestion concerning art in an age of culture. According to him, artistic work in the 1990s and 2000s is produced according to the media structure of late postmodernism, which includes the expectation of a positive, micro social transformation (ecological environment; local customs; the logic or repression of everyday life; questions of identity). This actually means that the art of multi-cultural Europe emerges in the context of the projected possibility of a united European identity and political space.

I have argued for a post-post conceptual art that accepts the basic heritage of 1970s conceptualism (dematerialization of the art object, the need to establish a connection between art theory and art practice). It also accepts post-conceptual art from the 1980s, (intertextuality; irony; ideological critique). But, in opposition to the previous decades, art from the end of the 20th and the beginning of the 21st century deals with social relations and attempts to bring about a “positive” transformation of local communities, i.e. a change in cultural signifying practices (from the museum and art system to the mass-media). Cultural studies are the referent framework for this type of art.

Institutional context

According to Denegri, the contemporary art scene emerges in an institutional context that is inherited from the past, but which at the same time includes “changes [that] typically resulted from the total change in social, political and cultural circumstances in the last decade.”ibid. In an institutional sense, the following models are characteristic of this:

1. Official state institutions, among which the Museum of Contemporary Art in Belgrade, and the Museum of Contemporary Art of Vojvodina in Novi Sad are the most important;

2. Independent artistic associations that function as non-governmental organizations, (with regard to exhibitions and production, this kind of model was the most important in the previous decade, when official cultural institutions, because of their ideological orientation, did not follow current and relevant art trends. Some examples of this are ex Center for Contemporary Art, Cinema Rex, and the Center for Cultural Decontamination. These institutions were founded during the 1990s and some are as recent as the Remont Association; the Center for New Media kuda.org (Novi Sad); Dez.org; Kontekst gallery; TKH: Walking Theory; Second Scene; O3one gallery; Prelom collective; Art Clinic; etc.);

3. Private artistic collections became more widespread only during the 2000s. Some of them collect only recent artistic practices, (Telenor collection), while others specialize in all of 20th century Serbian art, (including the most recent Vuji?i? collection). New trends are also the basis of private museums. Examples include the Macura Museum located between Belgrade and Novi Sad, and the Zepter Museum in Belgrade. Private initiatives and the creation of private cultural centers should also be mentioned here, including ITS-Z1 (International Test Site) in Ritopek (near Belgrade), founded by New York-Belgrade based artist Dragan Ili?,, and also Third Belgrade (under construction),founded by Belgrade based artist Selman Trtovac.

The Museum of Contemporary Art in Belgrade is one of the oldest and most important institutions for contemporary art in the country. It was founded in the 1960s. A crucial turn in the museum’s politics occurred in 2000, when Branislava An?elkovi?, a former director of the Center, became a director of the Museum. A new permanent exposition installed at that time constituted a break with the traditional, modernist, linear, and historicist interpretation and presentation of modern art, ushering in the incorporation of contextual and cultural interpretations. During the 2000s the museum realized important historizations of Serbian art in the 20th century through retrospectives of important artists such as Petar Dobrovi?, Ivan Tabakovi?, Petar Lubarda, Dušan Otaševi?, Bora Iljovski, Raša Todosijevi?, Neša Paripovi?. This included also conceptual art of the 1970s and artistic practices from the 1990s (On Normality: Art in Serbia 1989-2001 [2005]). The museum also restored international cooperations (Conversation[2001 ]; or The Last East European Show[2003]). Unfortunately Museum is closed at the moment because of reconstruction and it contributes to recent art activities through separate gallery named the Salon of Museum of Contemporary Art.

The Museum of Contemporary Art in Belgrade is one of the oldest and most important institutions for contemporary art in the country. It was founded in the 1960s. A crucial turn in the museum’s politics occurred in 2000, when Branislava An?elkovi?, a former director of the Center, became a director of the Museum. A new permanent exposition installed at that time constituted a break with the traditional, modernist, linear, and historicist interpretation and presentation of modern art, ushering in the incorporation of contextual and cultural interpretations. During the 2000s the museum realized important historizations of Serbian art in the 20th century through retrospectives of important artists such as Petar Dobrovi?, Ivan Tabakovi?, Petar Lubarda, Dušan Otaševi?, Bora Iljovski, Raša Todosijevi?, Neša Paripovi?. This included also conceptual art of the 1970s and artistic practices from the 1990s (On Normality: Art in Serbia 1989-2001 [2005]). The museum also restored international cooperations (Conversation[2001 ]; or The Last East European Show[2003]). Unfortunately Museum is closed at the moment because of reconstruction and it contributes to recent art activities through separate gallery named the Salon of Museum of Contemporary Art.

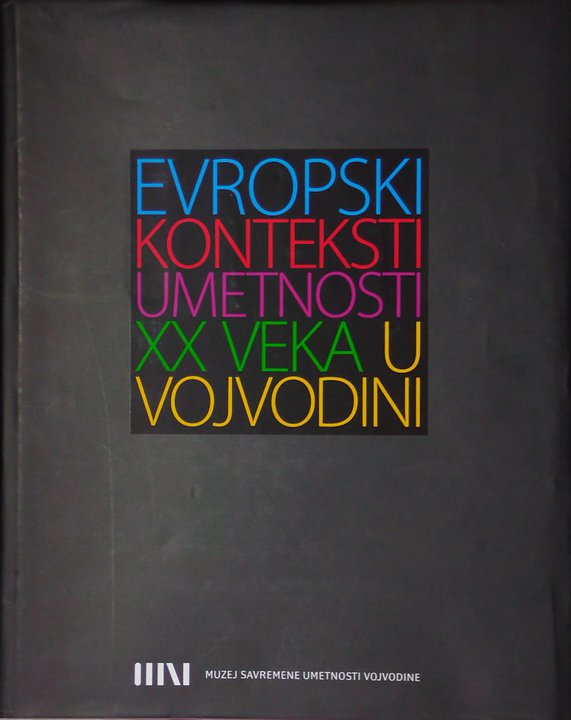

The Museum of Contemporary Art of Vojvodina in Novi Sad emerged from a series of institutional changes and transformations, from being a simple gallery for the presentation of recent art in the northern province of Vojvodina to being a real museum, (the museum directors Dragomir Ugren and later Živko Grozdani? were responsible for those important changes). In the 2000s the Museum organized several important retrospective exhibitions of artists who were protagonists of the so-called New Artistic Practices in Vojvodina during the 1970s (Slavko Matkovi?, Balint Sombati, Vladimir Kopicl, the groups KôD, (? and Verbumprogram), presentations of private collections, and most importantly, historical surveys of 20th century art in Vojvodina, (Central European Aspects of the Avant-Gardes in Vojvodina, 1920-2000; European Contexts of Art in Vojvodina in the 20th Century).

Remont was founded as an independent artistic association in 1999, while the gallery was opened a year later. The Association was founded by a group of artists who were active in the local and international art scenes during the 1990s.Today the members of the curatorial team are Darka Radosavljevi?, Saša Janji?, Miroslav Kari? and Marija Radoš.

Remont was founded as an independent artistic association in 1999, while the gallery was opened a year later. The Association was founded by a group of artists who were active in the local and international art scenes during the 1990s.Today the members of the curatorial team are Darka Radosavljevi?, Saša Janji?, Miroslav Kari? and Marija Radoš.

The Center for New Media, kuda.org, is an independent art association from Novi Sad that works in the field of the production and promotion of digital technologies and new media art. As the program of the organization states: “New Media Center_kuda.org is an independent organization which brings together artists, theoreticians, media activists, researchers and wider public in the field of Information and Communication Technologies. In this respect, kuda.org is dedicated to the research of new cultural relations, contemporary artistic practice, and social issues.”

Kontekst gallery was founded as a self-organized, alternative exhibition space in Belgrade in 2006.The aims of the organization and the gallery is to promote young artists and, through art activism, discuss recent and actual phenomena in contemporary art, culture and society. The members of the curatorial team are Vida Kneževi?, Ivana Marjanovi?, Marko Mileti?, and numerous volunteers. The work of the gallery became particularly visible after the exhibition Exception-Contemporary art scene from Priština in 2008 (the curators were Vida Kneževi?, Ivana Marjanovi?, Kristijan Luki? and Gordana Nikoli?). The exhibition was closed as a result of aggressive demonstrations by right wing hooligans.

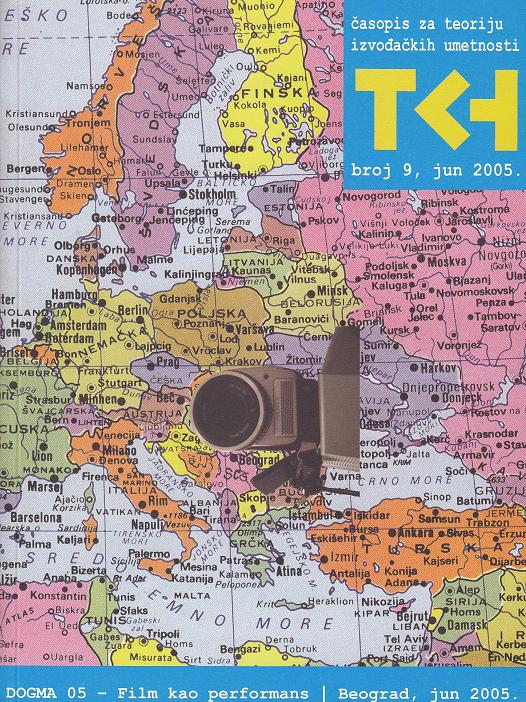

TKH: Walking Theory is an organization that was founded in 2000, first together with the Center for New Theatre and Dance, and later as an independent NGO. The main aim of the organization is the production, promotion, and theorization of the performing arts (performance, alternative theatre, etc.). Another important aspect of its work is the theoretical magazine,TKH (the organization is founded by Bojana Cveji?, Bojan ?or?ev, Sinisa Ili?, Jelena Novak, Ksenija Stevanovi?, Miško Šuvakovi?, Jasna Veli?kovi? and Ana Vujanovi?).

TKH: Walking Theory is an organization that was founded in 2000, first together with the Center for New Theatre and Dance, and later as an independent NGO. The main aim of the organization is the production, promotion, and theorization of the performing arts (performance, alternative theatre, etc.). Another important aspect of its work is the theoretical magazine,TKH (the organization is founded by Bojana Cveji?, Bojan ?or?ev, Sinisa Ili?, Jelena Novak, Ksenija Stevanovi?, Miško Šuvakovi?, Jasna Veli?kovi? and Ana Vujanovi?).

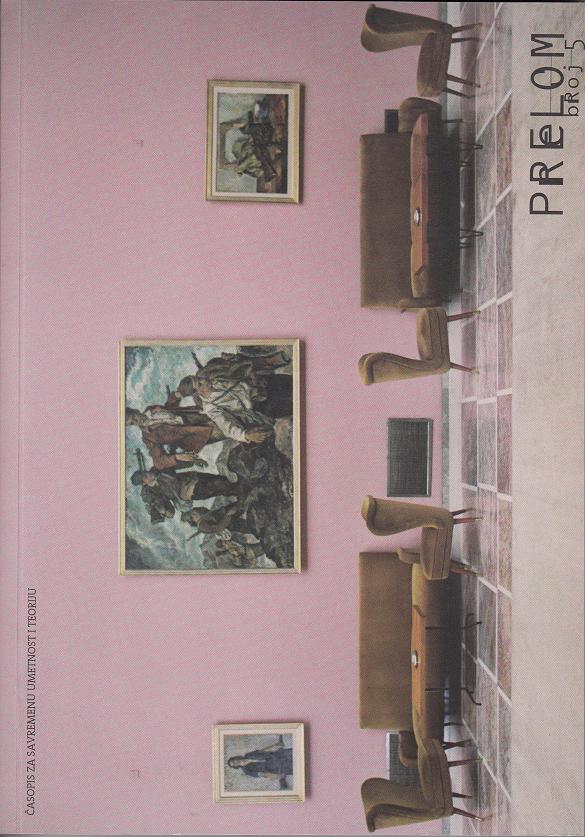

Prelom collective emerged from the theoretical magazine Prelom that has been published since 2000. The magazine was founded as a project by the School for History and Theory of Image inside the Center for Contemporary Art Belgrade. The aim of the magazine is the post-Marxist rethinking of pluralistic emancipatory politics: “The emphasis is placed on the proper understanding of the importance and power of representation and, especially, its role in the formation of ideological and political constructs of society.” The members of Prelom collective were younger theoreticians and curators: Jelena Vesi?, Dušan Grlja, Zorana Doji?, Dragana Kitanovi?, Vladimir Markovi?, Siniša Mitrovi?, Ozren Pupovac and Milan Rakita.

Dez.org is an independent association of artists, including Gordana Beli?, Dragan ?or?evi?, Tijana Kneževi?, Maja Radanovi?, Jelena Radi?, Dragan Rajši?, Maja Rako?evi? Cvijanov, Milica Ruži?i?, Ivana Smiljani?, Boba Mirjana Stojadinovi? and Boris Šribar. Its main aim is, “looking for a way to relate one’s own artistic practice with the practice of other artists; creativity in the local context, recognition of the ‘local’ in the wider frame and letting go of that ‘local’; examining the ways in which one can operate in the sphere of enriching opinions and ways of thinking; examining the possibility of knowledge distribution; communicating to the public and the private, and examining the borders between the one who ‘offers’ and the one who ‘receives’ art(…).”

Second scene is a project by numerous individuals and art organizations that are part of the alternative, independent, and unofficial art scene in Serbia (started in 2006). Originally, the project was composed of the following organizations: Prelom kolektiv, Stanica, TkH, Dez.org, Nova drama, Tehne, Stanipanikolektiv and Queer Beograd. The projects of Second scene are mostly presented in the alternative exhibition space Magacin in Belgrade.

Art Clinic is an alternative, utopian project of the informal artistic group Led Art from Novi Sad. It was founded by artist Nikola Džafo. Art Clinic tries to define an answer to the “sick society we live in, with the belief that art can cure and change the world.”

Art Clinic is an alternative, utopian project of the informal artistic group Led Art from Novi Sad. It was founded by artist Nikola Džafo. Art Clinic tries to define an answer to the “sick society we live in, with the belief that art can cure and change the world.”

Considering the numerous private projects in the field of art and culture, the Museum Macura, the first private museum in Serbia (the founder is Vladimir Macura), opened to the public in 2008 in Novi Banovci near Belgrade. It houses internationally oriented collection of 20th century art, with particular emphasis on the art of the historical avant-gardes of the 1920s, as well as later neo-avant-gardes and conceptual art from the 1970s.

The Zepter Museum, foundedby Madlena Zepter, in Belgrade with the collection oriented toward Serbian art of the 20th century, should also be mentioned here.

The Vujicic collection, owned by Zoran Vujicic, is the first private collection that undertook projects in the field of art publishing.

Other Belgrade institutions that promote and present contemporary art includet he Student Cultural Center; the Cultural Center Grad; the galleries Zvono and Haos; the Cultural Center at the University Library. There is also the October Salon; Belef; Mixer in Belgrade; the Nadežda Petrovi? Memorial in ?a?ak.. The Youth Bienale in Vršac that was active in the first half of the decade was also important for the local art scene.

The phenomenon that is crucial for understanding the art scene in Serbia is its evident internationalization after 2000. The participation of Serbian artists in important international art manifestations and exhibitions during the 1990s was sporadic. In this way, Serbian art over the last decade was produced in isolation, within a society that manifested antagonistic relations towards international “high” art. After 2000, however, the participation of domestic artists became more regular, and art from this part of Europe became internationally recognized within curatorial concepts of “Balkan,” i.e. “Eastern European” art.

Manifesta was particularly important in this regard, a biennial conceived as a mobile and fluid artistic platform whose aim is not the presentation of Western masterpieces but rather the horizontal networking of regional and local cultural identities with the projected vision of a united European cultural and artistic space.

At the same time, the creation of the international biennial and triennial network was also important. The series of “Balkan” exhibitions in the middle of the 2000s was particularly symptomatic for the break through of art from South East Europe and ex-Yugoslavia: In Search of Balkania 2002 in Graz, curated by Peter Weibel; Blut und Honig-Die Zukunft ist im Balkan in 2003 in Vienna, curated by Harald Szemann; and Inder Schluchten des Balkans 2003 in Kassel, curated by Rene Block. The beginning of the international contextualization of domestic art happened with the exhibition After the Wall-Art and Culture in Postcommunist Europeat the Museum of Modern Art in Stockholm, curated by Bojana Peji? and David Elliot in 1999-2000.

An example of internationalization of local art scene is October Salon, the most important annual art event in Serbia. Itwas established in 1960 and has functioned as a review of recent local artistic production, (in the beginning it represented the ideology of socialist modernism as semi official art style in communist Yugoslavia, and it functioned similarly to the traditional Paris salons). From 2000 onward, October Salon became an international event that is now being organized in a similar way to international biennials and triennials, and frequently with international curatorial teams, (the selectors of the Salon, from 2002 onward, were Lidija Merenik, Milanka Todi?, Anda Rottenberg, Darka Radosavljevi?, Rene Block, Lorand Hegyi, Bojana Peji?, and Branislava An?elkovi?).

When considering relations between the local and international art scene, the Dimitrije Baši?evi? Mangelos’ award for the best young artist should also be mentioned. The award is part of the Young Visual Artist Awards network that, in the last ten years, has produced some of the best new and young artists from Eastern Europe. The winners from Serbia from 2002 to 2011were Bob Miloševi?, Vladimir Nikoli?, Milica Ruži?i?, Milena Gordi?, Siniša Ili?, Katarina Zdjelar, Ivan Petrovi?, Ivana Smiljani?, Dušica Draži?, and Marina Markovi?, most of whom now have successful and internationally recognized careers.

When considering relations between the local and international art scene, the Dimitrije Baši?evi? Mangelos’ award for the best young artist should also be mentioned. The award is part of the Young Visual Artist Awards network that, in the last ten years, has produced some of the best new and young artists from Eastern Europe. The winners from Serbia from 2002 to 2011were Bob Miloševi?, Vladimir Nikoli?, Milica Ruži?i?, Milena Gordi?, Siniša Ili?, Katarina Zdjelar, Ivan Petrovi?, Ivana Smiljani?, Dušica Draži?, and Marina Markovi?, most of whom now have successful and internationally recognized careers.

Art in Serbia in the 2000s

I already mentioned that one of the central characteristics of the art scene in the 2000s in Serbia, but also within a more global framework, has been the absence of any mainstream that could be described by straightforward art historical categories such as style, school, or movement. This plurality and “immenseness” of recent Serbian art is evident on two levels:

1.On the level of art and media practices contemporary artists use equally and freely both traditional media (painting, sculpture) and media procedures that were inherited from post-conceptual practices.

2. Contemporary artists very often act and work within local contexts, but they also present their work within global, internationally oriented and networked art systems. This plurality, dispersion and horizontality makes it difficult to provide a precise historicization and categorization of artistic phenomena that emerge on the local art scene. Because of that, in the following remarks I will not try to give a precise, comprehensive classification of the “dominant trends” in Serbian art in the 2000s. Instead I will outline some problems that seem dominant in the work of some artists, and I will do so in full recognition of the fact that my remarks betray my own subjective perspective on events and activities in which I have myself often participated.

The most valuable and provocative aspects of the Serbian art scene in 2000 are, in my mind:

The problem of art’s politicization – thanks to the heritage of historical avant-gardes, neo-avant-gardes and conceptual art, the politicization of contemporary art means the transformation of aesthetic creation as a form of research of culture and society through art.

After the historical avant-gardes and conceptualism destroyed the idea of the autonomous art work, the “content” of art is not more aesthetic but social. This is a global trend in contemporary art: artists in their work investigate social power relations, systems of signification, as well as cultural and political and ideological practices within contemporary neo-liberal societies. Artistic work is thus restructured from being a work or masterpiece to a project; in other words,the practice of the creation of a an artwork is transformed into “research of art, culture and society.”Miško Šuvakovi?, „Umetnost u epohi globalizma“, grupa autora, Istorija umetnosti u Srbiji, XX vek. I: radikalne umetni?ke prakse 1913-2008, Orion Art, Belgrade, 2010.

On one hand, the politization of art in Serbia is a consequence of a specific context within which contemporary artists live and work. It is a society marked by turbulent historical and social changes that are the object of artistic thinking. On the other hand, international, neo-liberal art systems have a need to integrate only those artistic phenomena from Eastern and South-Eastern Europe that are recognized as “authentic”; as representations and manifestations of the specific cultural and political European “Other”. In this way, the politicization of art is also a specific “tactic” of local artists in their attempt to be recognized and integrated within the international art market.

In the field of “political” art practice we find artists such as Milica Tomi?, Zoran Todorovi?, Katarina Zdjelar, group Škart, Vladimir Nikoli?, Dragoljub Raša Todosijevi?, Živko Grozdani?, Ivan Petrovi?, Darinka Pop Miti?, Bojan Fajfri?, Goran Despotovski, Dušica Draži? and many others. One of the recent exhibitions that problematized the question of political engagement in art, i.e. the rethinking of emancipatory social politics through art, was Political Practices of Post-Yugoslav Artin Museums(Belgrade, 2009), but also the 49th October Salon, titled Artist-Citizen, which analyzed the relations between politics and contemporary art.

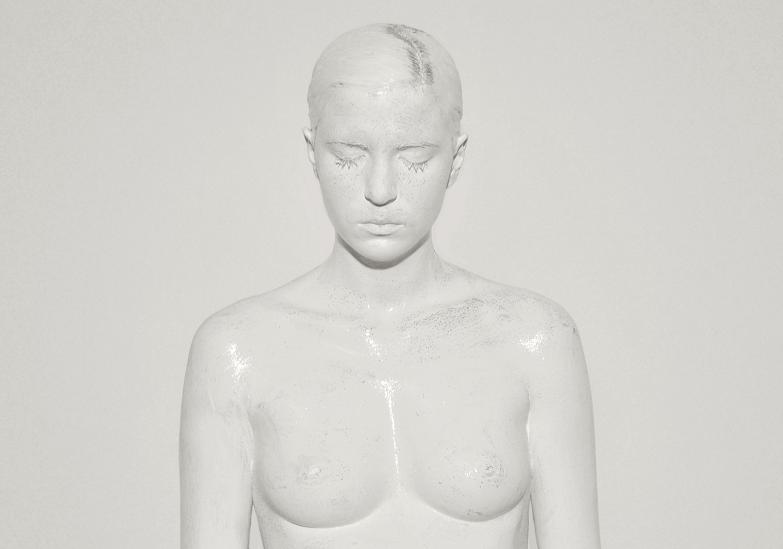

Art practices that directly problematize the phenomena of identity in art (feminist, gay, and queer strategies).- Closely related to the problem of engagement in art is also the question of identity, both personal and collective. Many artists work in the field of feminist or queer positions and they deal very often with the problems of gender. The notion of feminist art means that certain women artists mostly work with the assumption that gender identity is a cultural construction. Those practices question the notions of representation, power distribution, and gender selection within the process of the constitution of social hierarchies and signifying codes. The notion of queer means, “extinct, unconventional, eccentric, weird or behavior that is different from usual sexual, erotic or gender behavior”. Within contemporary cultural theory, particularly gender studies, the notion of queer marks different unusual ways of sexual behavior and unconventional identities: “ male homosexuality (gay), female homosexuality (lesbian), bisexuality, trans-sexuality, masochistic, sadistic, sadomasochistic, exhibitionistic, fetishistic, sodomy,transvestite, autoerotic, poli-sexual and cyber identity.”ibid.

In the field of feminine, feminist, gay or queer art practices we find artists such as Tanja Ostoji?, Ranko Travanj, Boris Šribar, Marina Markovi?, Siniša Ili?, Queer kolektiv, Marta Popivoda, Danilo Prnjat, Ivana Smiljani?, and others.

In the field of feminine, feminist, gay or queer art practices we find artists such as Tanja Ostoji?, Ranko Travanj, Boris Šribar, Marina Markovi?, Siniša Ili?, Queer kolektiv, Marta Popivoda, Danilo Prnjat, Ivana Smiljani?, and others.

The use of new, digital, and mass media technologies in art–I already mentioned that contemporary artists work in an extremely dispersive and hybrid space when it comes to media. Contemporary art deals not any more with the traditional category of the art work, object, but rather with data bases, archives, signifying cultural practices, mass media systems, and new digital technologies. Artists from Serbia who work in the field of digital media are Dejan Grba, Jovan ?eki?, Žana Poliakov, Rastko ?iri?, Nikola Pilipovi?, Marija Vauda, Marica Preši?, Vladan Radovanovi?, and numerous others. New media art has a significant tradition in ex-Yugoslavia, especially considering the New Tendencies movement that developed in Zagreb during the 1960s. The first experiments with new digital media were made by Zoran Radovi?, Koloman Novak, and Miroljub Todorovi?. Organizations that promote and produce art projects in the field of digital technologies are the Center for new media kuda.org from Novi Sad, and Cinema Rex from Belgrade (project KEF-Short Electronic Form is particularly significant; it was organized and initiated by the artist and activist Nebojša Miliki?).

The problem of contemporary painting – contemporary painting is characterized by a broad spectrum of practices that are defined by radical post-formalist or neo-informal abstraction, or by figuration inspired by post-pop art and the culture of contemporary mass media. Painting is here not treated as a space of expression, originality and the progressive development of an image through procedures of reduction, but rather as a space of inter-textual and visual simulation. Typical representatives of these new tendencies in painting in the in 2000s are Dragomir Ugren, Perica Donkov, Biljana ?ur?evi?, Sr?an ?ile Markovi?, Rada Selakovi?, Vladislav Š?epanovi?, Siniša Ili?, Dejan Grba, and numerous others.

[su_menu name=”Serbia Focus”]