ŠTO TE NEMA – A Living Monument: An Interview with Aida Šehović

ŠTO TE NEMA (Where have you been?) by Bosnian-born artist Aida Šehović is an annual nomadic monument to the victims of the 1995 Srebrenica genocide that has traveled internationally to 15 different cities from 2006 to 2020. This participatory public monument, consisting of more than 8,372 fildžani (small porcelain coffee cups) that have been collected and donated by Bosnian families from all over the world, addresses issues of trauma, healing, and remembrance. The first in a series of articles that make up our Special Issue Contemporary Approaches to Monuments in Central and Eastern Europe, this interview is occasioned by Šehović’s recent solo exhibition ŠTO TE NEMA (September 25-December 19, 2021) at the Laumeier Sculpture Park in St. Louis, which includes an archive of the project, alongside related works.

Susan Snodgrass: ŠTO TE NEMA began in 2006, 11 years after the Srebrenica genocide. Although the last iteration of this nomadic monument took place last year in Srebrenica-Potočari, your current exhibition at the Laumeier Sculpture Park in St. Louis is an archival survey of the work. What was the impetus for this 15-year project?

Aida Šehović: The impetus for the project actually came from my own personal relationship, not necessarily to Srebrenica – because I’m not from there, and my father and family are alive – but to Bosnia. We didn’t experience the magnitude of loss that many people from that area have experienced, but I was a refugee. We were displaced and forced to leave my hometown of Banja Luka. As a teenager, I lived with my family as a refugee in Turkey and Germany before immigrating to the United States in 1997. And so the questions about how this could happen, in the twentieth century, in Europe after World War II, after we said never again remained with me.

Art became a way for me to continue asking these central questions that drive me. I refuse as both a human being and an artist to live in a world where violence is normal. In the case of the 1995 Srebrenica genocide specifically, it happened within the United Nations safe area, which meant that the world reassured the Muslim population there that they were safe and protected before they were killed. The crimes were not hidden nor unexpected; they were visible. The United Nations soldiers on the ground opened their gates to allow the military, paramilitary units, and army to go in. I would say that the world was not just a witness or bystander, but complicit to an extent. And because it was so brutal and so clearly about eradicating a group of people based on their name, religion, and ethnicity, it was undeniable. When I began ŠTO TE NEMA, my motivation really came from a place of anger and disappointment at the world and humanity.

SS: Had you always envisioned ŠTO TE NEMA as something temporary?

AS: I had never imagined the work as a monument. It was actually conceived as a one-time performance. I never predicted that I would continue repeating this ritual on an annual basis, and that it would become this ephemeral, participatory, temporary monument. But that’s actually the beauty of it; that it continued to evolve and grow, even though the last iteration of it as a living monument was last year. Right now, it’s in this transition or transformation because I’m creating a permanent version of ŠTO TE NEMA at the Srebrenica Memorial Center, the site of the atrocities.

ŠTO TE NEMA nomadic monument on July 11, 2018 in Zurich, Switzerland. Photo: Sabine Rock © Aida Šehović.

SS: The monument consists of 8,372 porcelain coffee cups, which represent the number of Muslims who were systemically killed. Unlike traditional monuments that are static and permanent, each iteration of ŠTO TE NEMA takes place annually on July 11 (the anniversary of the Srebrenica genocide) in a public space of a different city, where the public is invited to fill the collected cups with coffee. How will this participatory, ritualistic monument be transformed in a permanent work?

AS: ŠTO TE NEMA began with 923 collected cups, and the collection of cups has been growing gradually every year. The question was always, what’s going to happen when we collect 8,372 cups, which is the number of confirmed deaths of people who were killed. Of course, the number is much larger, but this is the number that we use as a reference, because it was proven in courts legally. When the monument returned to Bosnia last year – it began in Sarajevo, but this was the first time it came to Srebrenica – we surpassed the number of cups. And because the cups were touching the ground for the first time, where men and women were separated and the atrocities began to take place, I felt that something had to change. It didn’t make sense to place those cups on any other ground afterwards.

I’m honored to be working on the permanent version at the Srebrenica Memorial Center and to give this work to them. The Srebrenica Memorial Center is founded by survivors, so it’s a very unique place and has a direct connection to people’s experiences and memories. They are building a museum there that will become a research center, not just for the Srebrenica genocide, but for all atrocities committed in Bosnia. It’s such a privilege to have ŠTO TE NEMA as part of their collection. Finally after 15 years, I have actually gotten comfortable with the fact that we’re dealing with a living work of art and with very difficult subject matter, so it’s okay not to know right away what it is going to look like and what it will be. Right now, I’m interested in simply going through this process collectively and deciding how to hand it over to the next generation, how to make a permanent monument that can still be relevant and, like ŠTO TE NEMA, really move and unite people regardless of their background.

ŠTO TE NEMA nomadic monument on July 11, 2017 in Chicago, USA. Photo: Manka Rabiye © Aida Šehović.

SS: What is the significance of coffee to Bosnian culture and to the issues of trauma, memory, and displacement that ŠTO TE NEMA addresses?

AS: Coffee drinking, or I would say, coffee sharing, is probably the most symbolic of Bosnian culture and tradition. The emphasis is on sharing, not on coffee. The cups that we use to drink coffee have a special name, fildžan; they are small porcelain cups without handles, similar to teacups. The majority of them are actually from China. The ritual of coffee was brought to us during the Ottoman Empire, then we took ownership of it and made it our own. It’s something that people do every day and it’s always a shared experience. Actually, when we make coffee in Bosnia, we oftentimes set aside a cup for an unexpected guest or somebody who might show up.

When I was doing research about Srebrenica, what struck me the most was a story that I came across about a woman who said that she missed her husband the most when she didn’t have anybody to share coffee with. I was interested in exploring through this work what loss means on a daily basis. How does it feel? What does genocide feel like after it has occurred? We often pay attention to such tragedies as they unfold, then we move on. But how does loss actually manifest itself in daily life? And so, a cup of coffee waiting for somebody became a clear, simple gesture that said so much.

Using collected cups as a material for the monument had its significance because it was clear to me from the beginning that genocide happened to all of us, not just the people of Srebrenica. The collective aspect is so crucial in how to approach the subject matter and discuss it. We have the Declaration of Human Rights. We defined genocide. We agreed on what it is. I don’t see how we can actually talk about preventing violence on a small scale, if we haven’t figured out how to stop genocide, the most organized form of violence. It’s literally thousands of people gathering together and making plans and strategies on how to kill thousands of other people.

SS: The coffee cups are donated by the public, then filled by the public at the site where the cups are gathered. Can you talk more about the participatory aspects of the monument?

AS: The first 923 cups were donated by the families from Srebrenica, by women of Srebrenica. Since then, the cups have been collected by people in each of the cities where the monument traveled to, as well as throughout the year by people who would send them to me. That gesture was expanded when the public was invited to participate in the construction of the monument, not just those who knew about it and were invited, but also passersby who just happened to be in the public space, which is why the location is so important to each installment of the work. The monument was always set up in a public square, a historical or significant place of gathering for each specific city. It had to be visible and truly open, because often when we talk about public art there’s almost a romantic idea of what that is. But how do you actually make the work truly public and inclusive?

After the first few years of installing ŠTO TE NEMA, it was clear to me that in order to really include people and make them feel welcome, we had to remove all signs and symbols of identity. What that meant was if you were to show up at a public square where we were building the monument, there was no visible information about it on site. You had no idea what was happening. You just saw cups, the making and pouring of coffee, and people gathering.

SS: What is the meaning of the monument’s title, which translates in English to Where have you been? Obviously, it’s about those that have been lost, but isn’t there a connection to a Bosnian folk song?

AS: Yes, there is. ŠTO TE NEMA can also mean “why are you not here?” or “why are you not returning?” The title is taken from a famous poem written by Aleksa Šantić. It’s a love song about longing for a loved one, a loved one who’s not returning. The poem then became a song made famous by the singer Jadranka Stojaković.

SS: What is the length of the piece — a few hours, a few days? Is the whole process recorded, and does the documentation become an aspect of the work?

AS: At the beginning, each iteration always took a whole day. We then had to move at a different speed as the number of cups kept growing. We would begin early in the morning and end in the evening, then spend several hours washing everything because the monument would be deconstructed. The central idea is that the monument is alive while the gesture of remembrance is being performed. After that, the monument sort of sleeps, or the cups go back into boxes. If we think about time in linear terms, then yes ŠTO TE NEMA is temporary and ephemeral. But if we think of time differently, everyone who holds a cup is forever connected to it because of their specific memory and unique relationship to the monument.

I knew from the beginning that it was impossible to document each iteration of the monument objectively. Yes, I would document it in video form, and of course there are photographic images, but I was under no illusion that I could recreate that feeling for you if you weren’t there. Also, my memory of the experience can be very different than yours, even though we were at the same place, because you spoke to different people than I did and have a different relationship to the work. It’s impossible to embody all of that.

I spent a long time thinking, of course, and there were opportunities to present ŠTO TE NEMA outside of the July 11th marker of the genocide, however I refused to do it. Then in 2019, I was invited by the Auschwitz Institute for Genocide Prevention to be included in something called the ARTIVISM Pavilion that was organized during the 2019 Venice Biennale. The Biennale invited the Auschwitz Institute to create this pavilion, then the curator actually ended up uninviting or excluding us. We were not part of the official Biennale in the end, but we presented the archive of the monument at ARTIVISM Pavilion anyway. That was a unique opportunity because by then I had had 14 years to think about how to show the monument in an exhibition setting; we had time and resources to come up with the best solution for the space. And then on July 11 we set up ŠTO TE NEMA in a public square in Venice just like all the previous years.

Aida Šehović, ŠTO TE NEMA (Spatium Memoriae), ongoing since 2006. 8,372+ collected porcelain coffee cups, metal shelving unit. Courtesy of the artist, New York. Photo by ProPhotoSTL.

SS: So the work’s presentation at Venice, even if somewhat interventionist, marked a shift in how you thought about the durational life of ŠTO TE NEMA?

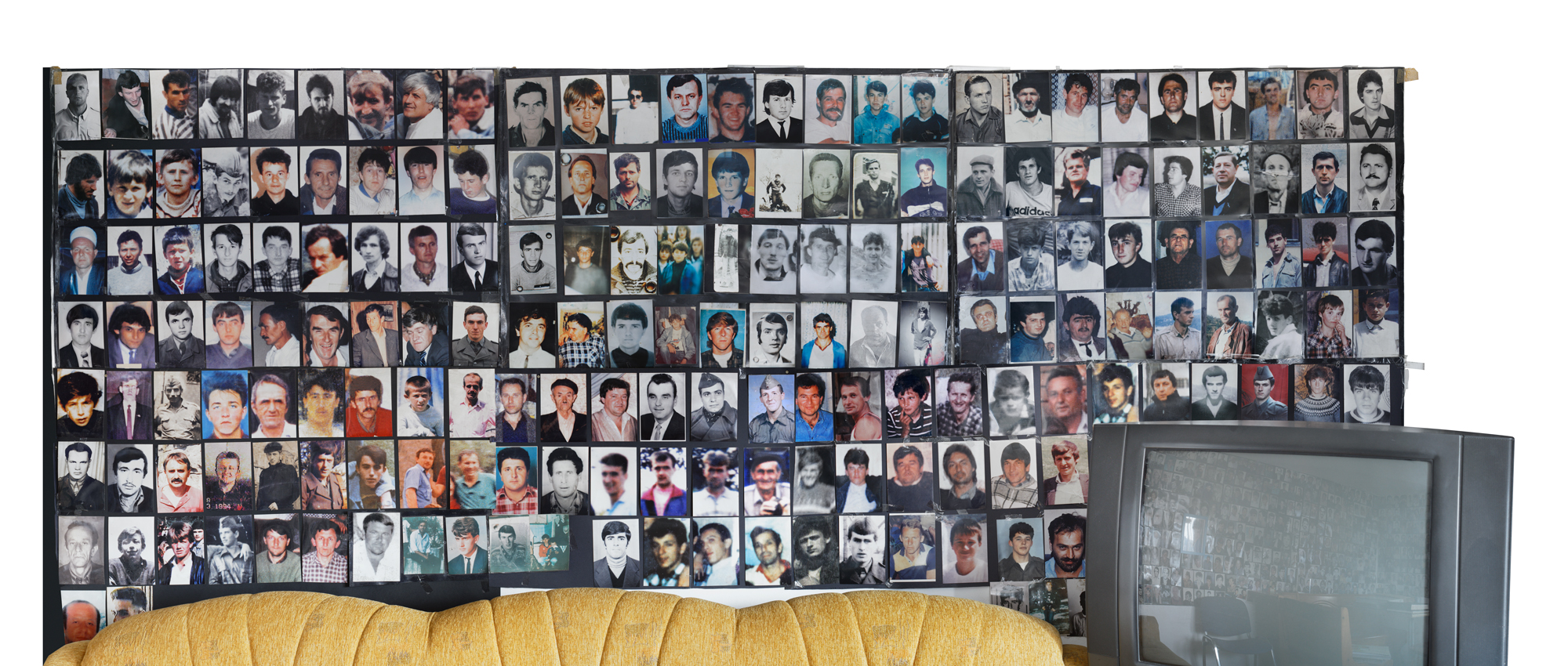

AS: Yes. I worked with the Auschwitz Institute to build an archive of ŠTO TE NEMA consisting of a series of shelving units to house the cups or display the monument in its dormant state. The design of the shelving units is based on the storage system used by the International Commission for Missing Persons, where they store and identify human remains before they are buried. The complete Archive is currently being presented at Laumeier. It’s the shelving units with the drawers filled with 8,372 plus cups, as well as posters from all the past iterations in the official language spoken in the country hosting the monument. Also on view is a related body of work called Family Album, a photo installation as a replica of the office walls of the Women of Srebrenica Association, one of the survivor groups. Each wall of Family Album consists of copies of portraits of family members lost in the genocide that the association has been collecting and taping to their office walls for a long time.

Family Album photo Andres Ramirez © Aida Šehović:

SS: What do you envision for the exhibition in St. Louis? It seems like a perfect site, not only because of Laumeier’s long-standing commitment to public art, but also because St. Louis has the largest Bosnian immigrant community in the United States. But there is also a public who is probably unfamiliar with this history. So you have two publics.

AS: Yes, the work has always been inclusive even though it speaks to a specific time and place, and to a specific atrocity, it is ultimately about loss on a human level. Including and reaching out to these different publics has been important from the beginning. The context is ideal because the exhibition is not being hosted by a Bosnian organization or the Bosnian community, but by a public sculpture park that’s part of St. Louis with its own history. That’s already meaningful. We have worked really hard to make the Bosnian diaspora community feel included and a part of the exhibition. For example, all the literature and social media announcements related to exhibition are bilingual.

Another challenge specific to this context is that we are not building the living monument, but rather exhibiting the Archive of the project, so the real question was how to create space for Bosnian families, especially the population from the area of Srebrenica, who are living here in St. Louis. There are more than 300 families whose members have survived the genocide, so they are directly impacted. We held a private event for the Bosnian community who came and spent the whole day placing the cups inside the shelving units instead of me doing this alone with the installation team.

SS: I see a lot of connections, for instance, between the horrific events symbolically raised in ŠTO TE NEMA and the anger and loss surrounding the shooting of Michael Brown by a white police officer in 2014 in North Saint Louis County, which incited social unrest and brought worldwide attention to this predominately black community. The key challenge is how to make visible those lost to the abuses of power.

AS: For the wider St. Louis community, remembering that we are human first and foremost is the most important. Because I think anybody can understand loss; it’s part of being alive. But unnatural death, death by an act of violence, that’s where we connect. So hopefully we are able to speak about loss through the work and the exhibition in that way.

In conjunction with the exhibition, we are also organizing a conversation about monuments. The discussion about public monuments specifically in the United States is finally becoming relevant and is happening, even though it’s long overdue. I’m inspired that I live here and can witness and take part in America confronting its problematic and painful history and being the driving force in this conversation about monuments. Hopefully we can put ŠTO TE NEMA into that context, because the work actually precedes this conversation that’s unraveling now.

Also, I think it is important to note that making monuments or using public art as a way to remember our collective history is really complicated. It’s very hard for the work to fulfill all the different roles. Also, if you’re telling other people’s history, there’s accountability, right? There are ethical values that you need to maintain and follow and respect. Speaking about ŠTO TE NEMA on a conceptual level, I’ve always been interested in deconstructing the idea of a public monument. Yes, I had the idea. But it’s not my work, it’s our work. I’m just a caretaker. There are so many people who have contributed to it in so many different ways. It all has value and is all part of its fabric. That’s what it means to make a truly collective and public monument.

ŠTO TE NEMA nomadic monument on July 11, 2019 in Venice, Italy. Photo by Adnan Šaćiragić © Aida Šehović.

SS: We’ve talked a lot about the presentation in St. Louis and the ways in which local communities have been and will continue to be engaged throughout the exhibition. ŠTO TE NEMA has been staged in cities such as Chicago, Venice, and Zurich, but can you talk some more about the monument’s reception in Bosnia?

AS: I’m glad you were asking that question, because one thing that we haven’t discussed is that ŠTO TE NEMA has two different functions here (abroad) and at home. We briefly mentioned Michael Brown and some of the conversations that are unfolding in this country. To me, it’s so important to remember when talking about systemic racism or homophobia or genocide as an example, that they’re all related things. That’s why the conversation about intersectionality is so important, because these are all different forms of mass violence and oppression against groups of people.

It’s crucial to keep that in mind and stay connected, and not get lost while focused on whatever you’re fighting for. I say that because half of Bosnia’s population was displaced, which means that half of the country still lives abroad, mainly in Western Europe and North America, so we’re a fairly young immigrant population in many countries. One thing that we often forget is that the majority of us are Muslims, and the Western world has very little tolerance for Muslims owning their identity or taking up public space in such a way. This is a monument to Muslims, and it’s a big deal to have it occupy a place like Daley Plaza in Chicago, or Copley Square in Boston, or Washington Square Park in New York. Thus, its function and role become much more important abroad than at home. In Bosnia, it is a reversal of that – it’s a reminder to the people who have remained and live there of the solidarity and empathy the world has for them.

SS: You began ŠTO TE NEMA 15 years ago as a one-time performance and it has evolved into something else. It’s amazing how much the work anticipated current conversations around monuments, commemoration, and transitional justice. How do such participatory monuments offer counternarratives to the traumas of history that traditional monuments cannot?

AS: I’ve been thinking about that clearly a lot. Because to me, the problem with permanence – and I’m not saying that nothing should be permanent or that the monument shouldn’t be permanent – is that the conversation sort of stops. The beauty and strength and power of an ephemeral temporary work, and of course I’m thinking of ŠTO TE NEMA here, is that this has been an ongoing conversation. And like I said, at the beginning I didn’t wake up with some perfect idea of what it was going to be; no human can do that. It’s an ongoing conversation that you have with the public and the community, that the work has, and that I have with the people I work with. That is the work’s main strength.

But now I’m at the stage where I have to and want to think about permanence. What I’m grateful for in the case of ŠTO TE NEMA is that it feels natural to bring it to Srebrenica and create a permanent version because it has earned its place. This was so clear last year when it arrived or “returned” to Srebrenica. People kept saying, “The cups are coming home.” I got goosebumps from that. It’s like, this is beyond me and anybody else. The cups have earned their place and they are returning home. This is where they belong.

This interview took place over Zoom in September 2021. It has been edited for length and clarity.

This article is part of the Special Issue Contemporary Approaches to Monuments in Central and Eastern Europe. You can find links to the other articles in the special issue below: