Photography: The Lingua Franca of Performance Art?

As Michelle Henning points out in her book Photography: The Unfettered Image (2018), “from its inception, photography was a means to set images free, to allow them to go traveling, to transfer, to be projected, translated, fragmented, reconstituted and reversed, to be reimagined and re-embodied.”(Michelle Henning, Photography: The Unfettered Image (New York: Routledge, 2018), p. xi.) How does this perspective contribute to understanding the medium beyond its treatment in art museums, which usually emphasize uniqueness and authorship? How does highlighting the concept of images as “migratory, journeying, wandering and vagabond”(Henning, p. 8.) alter our approach towards photographs documenting the performance art of the late 1970s, when photography served as a common tool, a lingua franca, and a medium that allowed artists to communicate their ideas?(This article is based on a presentation I prepared for a conference organized within “Resonances: Regional and Transregional Cultural Transfer in the Art of the 1970s.” It provided an opportunity to rethink and revise my previous publications on the topic. See Hana Buddeus, Zobrazení bez reprodukce? Fotografie a performance v českém umění sedmdesátých let 20. století [Representation without Reproduction? Photography and Performance in Czech Art of the 1970s] (Prague: UMPRUM, 2017); “Infiltrating the Art World through Photography. Petr Štembera’s 1970s Networks,” in “Actually Existing Artworlds of Socialism,” ed. Reuben Fowkes, special issue, Third Text 32, no. 153 (2018): pp. 468–484; “The Photographic Conditions of the Happening,” in The Sešit Reader. The First Ten Years of Notebook for Art, Theory and Related Zones 2007–2017 (Praha: AVU, 2020), pp. 228–245.) Finally, how does this view align or contrast with approaches that emphasize the materiality of photography?

Drawing upon the premise that performance documentation constitutes an integral component of performance art, this essay suggests that emphasizing its diverse material manifestations may enhance our understanding of the contextual conditions that shaped cultural transfers during the era of the Iron Curtain, as well as the reception of performance art. It specifically deals with several examples of performance art documentation produced in Czechoslovakia in the 1970s that are relevant in this regard.

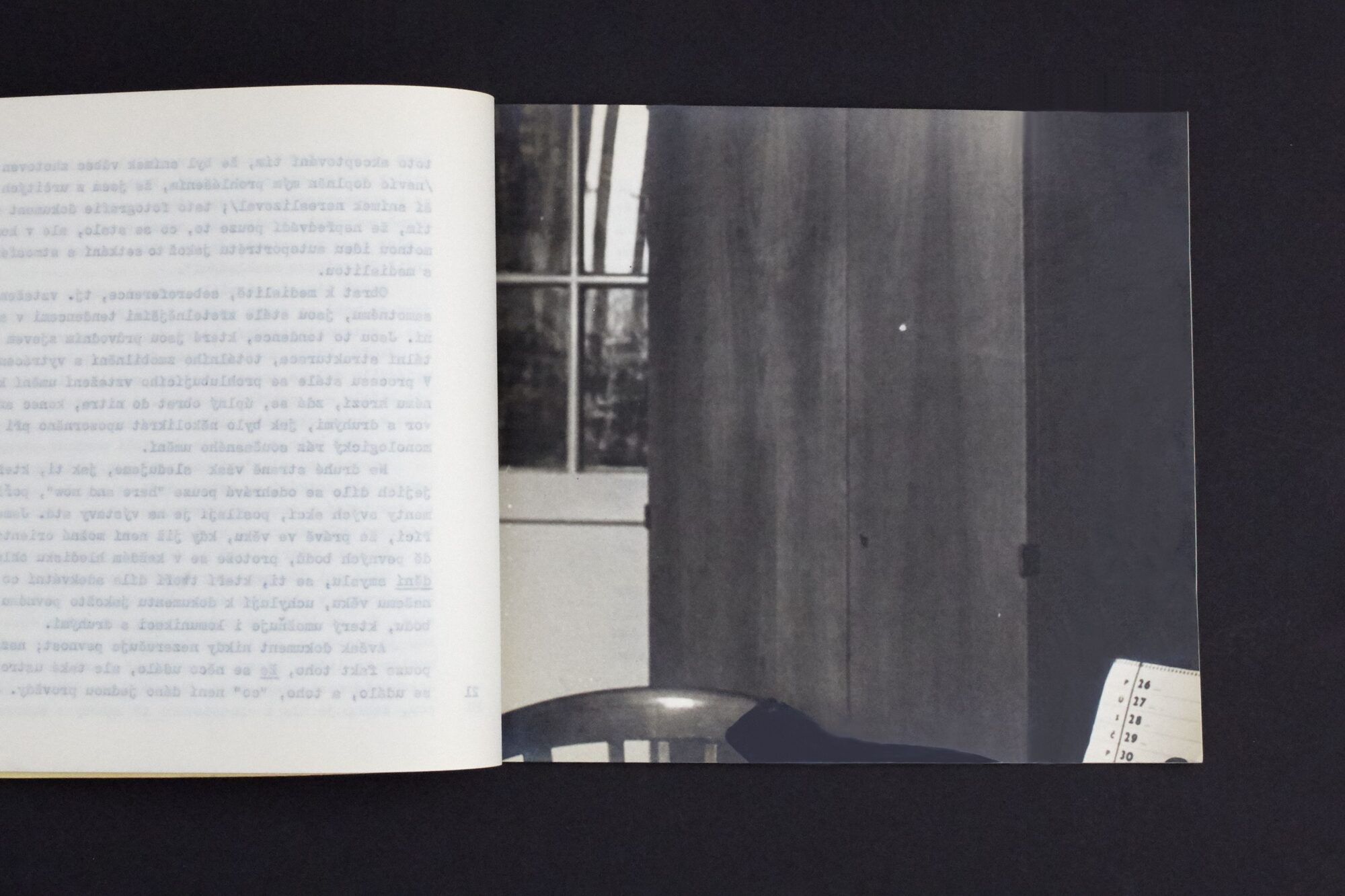

Petr Rezek. Narcisovo neshledání (Narcissus’s Non-Encounter), 1970s. Black and white photograph in an undated samizdat publication on performance. Private collection. Photograph by Anežka Pithartová, Institute of Art History of the Czech Academy of Sciences.

Documentation as a Constituent of Meaning

In an essay from 1977, “Dokumentované umění” (Documented Art), Petr Rezek, a Czech philosopher and active participant of 1970’s performances in Prague, described his attempt to make a photograph of himself, a self-portrait. Although—or perhaps, because—this attempt failed, he published the resulting picture in one of the samizdat collections of his texts. He intended to create a portrait, but no person was captured in the black-and-white photograph. Instead, the foreground shows the top rail of an empty chair with draped fabric, possibly a piece of clothing, and a fragment of a desk calendar. The desk itself lies outside the frame, suggesting that the camera was placed upon it. In the background, we observe a wardrobe, a white wall, and a window. According to Rezek’s account of the event, this picture was taken unintentionally, due to a mistaken self-timer setting. Nevertheless, he embraced this photo as his self-portrait instead of retaking it and he decided to name it Narcisovo neshledání (Narcissus’s non-encounter), referring to Petr Štembera’s seminal performance Narcissus, realized in several different versions in the 1970s. In a way, this choice validated Rezek’s argument that “rather than the document merely testifying to an action taking place, it itself constitutes the meaning of such an action.”(“Dokumentované umění,” in: Petr Rezek, Performance (undated samizdat), p. 21. Revised version of the text reprinted in: Petr Rezek, Tělo, věc a skutečnost (Prague: Ztichlá klika, 2010).) According to Rezek, a document not only records what happened but is an event in itself, something that happens (sám se děje); it helps create the meaning and acts as a fixed point that allows communication with others.

By asserting that photographic documentation serves not only as evidence but also as a constituent of meaning, Rezek addresses the most critical issues encountered when dealing with photographic documentation of performance art from that period, created in the areas under the communist rule. This argumentation actually connects the samizdat publication by the Czech philosopher with scholarly writings by Philip Auslander, who has also challenged the binary opposition or antagonism between live performance and its image that has traditionally determined the discourse on performance art. Auslander argues against liveness as an ontological condition and as a site of resistance, demonstrating that the relationship between the live and the mediatized is characterized more by mutual dependence, influenced by cultural and historical contingencies.(See Philip Auslander, Liveness: Performance in a Mediatized Culture (London: Routledge, 1999).)

Circulation of Performance Art through Photography

If performance art found fertile ground in the then communist Czechoslovakia, its success went hand in hand with its ability to spread easily through informal channels via photography, regardless of the unavailability of institutional backing. It is a well-known fact that in the 1970s, the art world in Czechoslovakia operated in challenging conditions, even when compared with Poland or Hungary. There was almost no possibility of performing in gallery spaces or public institutions. Typically, these events were organized informally and held in private settings or even outdoors. On occasion, they found a venue within art museums, where some of the participants held positions that allowed them to arrange informal gatherings inaccessible to the general public.

Exchanging photographic documentation was therefore often the only possible way for this type of art to circulate both on a local and international scale. The conveyance of photographs within ordinary postal envelopes among artists, curators, and collectors rarely attracted the attention of censors, facilitating their dissemination and presentation beyond the confines of Czechoslovakia. To mitigate the risk of interception, documentation might have been sent in special packages separate from the letters in which the artists explained their artistic intentions or wishes regarding the layout or installation.(That was the case of Petr Štembera’s preserved correspondence with Roger D’Hondt in his archive.)

The absence of formal institutional support found a partial substitute in the circulation of images through foreign publications and the distribution of prints for exhibitions abroad. The material traces of this circulation can be found in various collections of artists and curators, either in the form of photographic prints or as photomechanical reproductions printed in art magazines and exhibition catalogues. They witness the actual use of images during times when photographs representing the live performances often traveled worldwide on behalf of the artists.

Petr Štembera, one of the prominent Czech performance artists based in Prague, was among the most successful in gaining his reputation through sending photographic documentation to artists and curators abroad. Among the recipients of his intense correspondence were Klaus Groh, who included Štembera in his book Aktuelle Kunst in Osteuropa (Contemporary Art in Eastern Europe) in 1972, Tom Marioni, who published a special issue of the magazine Vision dedicated to Eastern Europe, and Henryk Gajewski who ran Remont Gallery, associated with a student club at the Warsaw Technical University.

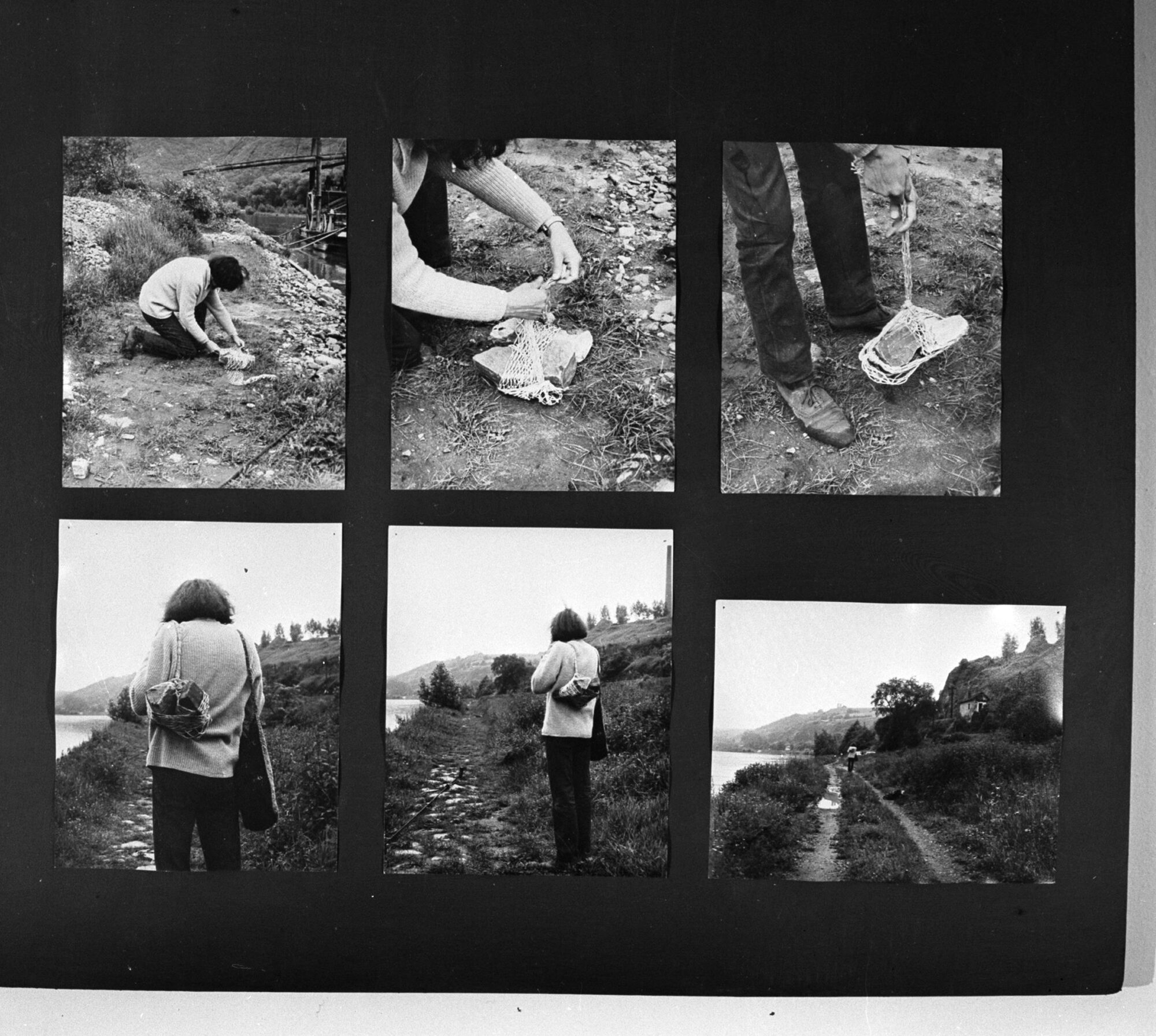

Petr Štembera. Transposition of Two Stones, 1971. Black and white photograph. From Štembera’s solo exhibition at the Remont Gallery in 1974. Private collection. Image courtesy of Petr Štembera and Henryk Gajewski.

In addition to well-known transnational events, such as I AM, the International Artists Meeting in 1978 (a week-long gathering that included lectures and performances and featured artists and curators from all over the world) Gajewski organized Štembera’s solo exhibition in 1974, as well as a 1976 group show featuring three Prague-based performance artists—in addition to Štembera, Jan Mlčoch and Karel Miler. In Gajewski’s archive, there are several photographs documenting Štembera’s solo exhibition, providing a rare glimpse of the display. Each piece was represented by several photographs mounted on a black board and hanging from the ceiling.(For more about Gajewski and Štembera see Buddeus, “Infiltrating the Art World,” pp. 480–482. See also Katarzyna Urbańska, Henryk Gajewski. Od konceptualizmu do sztuki interpersonalnej (Warsaw: Instytut Sztuki PAN, 2022).)

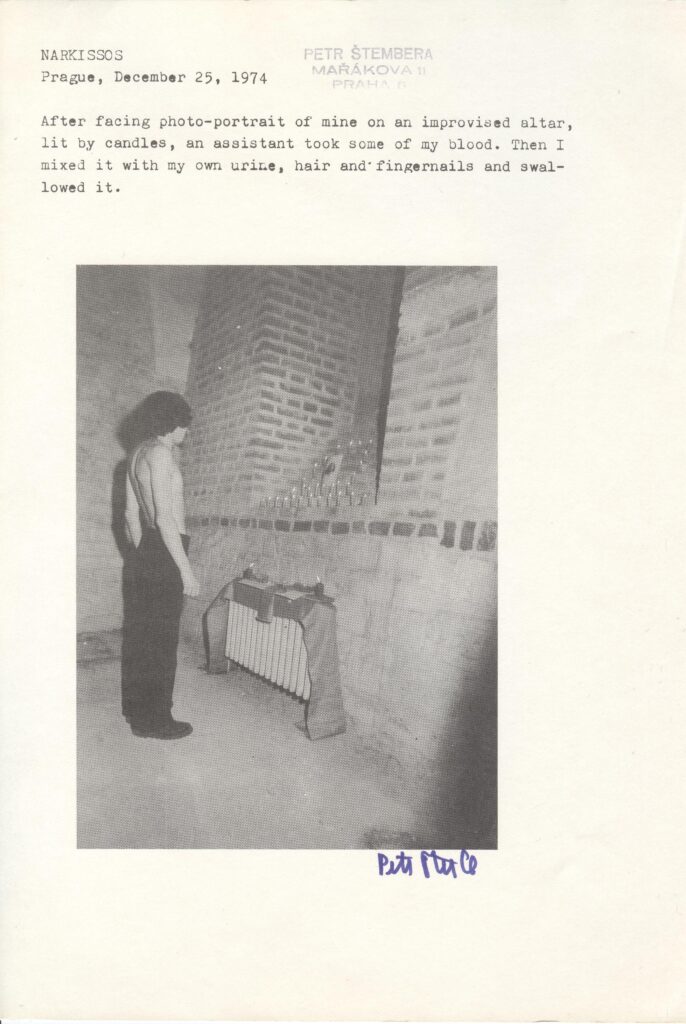

It was only later, in the second half of the 1970s, that Štembera began to create live performances (though still photographically documented) for an audience present on-site. The breakthrough event in this respect was the performance Narcissus, mentioned above as an inspiration for Rezek, first realized in Prague in 1974 and presented in various modified versions in the years that followed. In this performance, Štembera explored the possibilities of self-encounter by looking at his portrait photography, examining the image of himself in the mirror, and by consuming his own bodily fluids and cells. He described the first Narcissus performed in Prague as the following: “After looking at my portrait (photograph) on an improvised altar lit by candles, my assistant took some blood from my vein with a syringe. This I mixed with my urine, hair, and nails which I had cut off. I then drank this potion, again my eyes fixed on the altar.”(These textual descriptions might have also undergone some changes over time. In the signed A4 piece reproduced here, the text differs slightly from the one I quoted from the Artlist database: https://www.artlist.cz/en/works/narcissus-no-1-103594/, accessed February 17, 2024.)

Petr Štembera. Transposition of Two Stones, 1971. Five black and white photographs. New Reform Archive, collection Roger and Marie Hélène D’Hondt, Belgium. Image courtesy of Petr Štembera and Roger D’Hondt.

His Daily Activities, a series of performances for a camera from the early 1970s, dealing with routine actions, such as rolling up sleeves, typewriting, tying shoelaces, or fastening buttons are mainly found in collections outside Czechoslovakia and, thus, virtually absent from Czech collections, as the artist stopped displaying his photographic works after he turned to live performance in 1974. The most important of these early works is probably Transposition of Two Stones from 1971, which involved enveloping the stones in netting, effectively creating a DIY mesh bag, and then carrying them on the shoulder along a path on the outskirts of Prague. The documentation of this piece can be found in various forms and may include different numbers of photographs, accompanied by typed description, and may or may not include a map. Through Belgian collector and gallerist Roger D’Hondt, who ran New Reform, a non-profit art center in Aalst, I learned that Štembera not only sent him the photos of Transposition of Two Stones with the intention to exhibit them but that he also aimed to sell a signed, limited edition of five black-and-white photographs documenting his action. According to the preserved correspondence, the purpose of this initiative was more about spreading awareness and bringing the artwork to the audience, rather than making money, thus this attempt to enter the art market may be considered rather exceptional.(Buddeus, “Infiltrating the Art World,” pp. 475–477. )

Rezek wrote about photographic documentation as a basis for communication. Speaking about the Czech context and leaving aside the different financial and technical possibilities, Štembera’s use of photographic documentation was not especially innovative. Photography served for many as an easily reproducible medium, as the lingua franca of performance art. Its importance was rooted in its utility rather than its aesthetics. However, the specific form of the use of this almost universally understood language depended on many factors. If we look more closely at its uses and direct our focus towards the various dialects, idiolects, and sociolects it encompasses, we can also learn more about the nature of the art it transmitted.

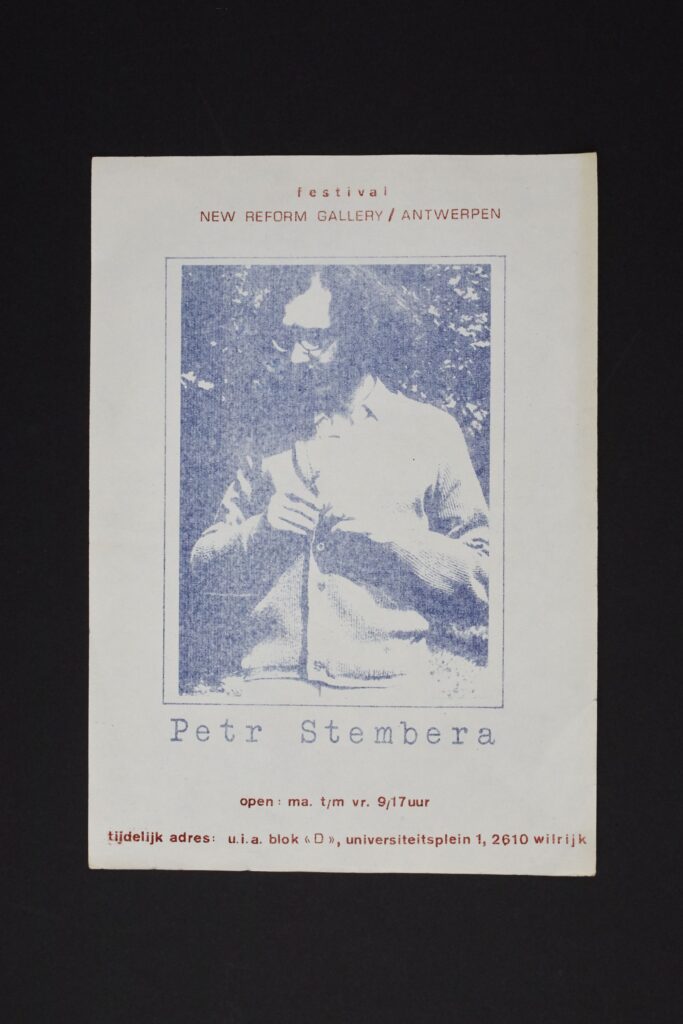

Exhibition poster for Petr Štembera’s solo exhibition in Antwerp in 1974. Photomechanical reproduction on paper. Private collection. Image courtesy of Petr Štembera and Roger D’Hondt. Photograph by: Anežka Pithartová, Institute of Art History of the Czech Academy of Sciences.

The fact that the Daily Activities series was crucial for Štembera at the time is confirmed, for example, by a reproduction of a photograph showing him buttoning his shirt, which was used on the poster for his solo exhibition in Antwerp organized by D’Hondt in 1974. Such low-quality reproductions, which appeared in non-profit publications in the West as well as in unofficial and semi-official publications in the East were one of the typical outputs of these exchanges. In addition to gelatin silver prints, photomechanical reproductions played a crucial role in facilitating international transfers. Besides the posters and invitation cards, the reproductions in exhibition catalogues and in foreign magazines were seminal in distributing the original art piece to a wide audience. Through the catalogs, some of the exhibited works reached a secondary audience but also returned to the archives of the authors and to libraries, where they continue to serve as a source of information to this day. It is evident, that the possibility of putting their work in an international context, as was the case with Karel Miler’s Measuring (1974) reproduced next to Douglas Huebler’s Piece #31 in Flash Art no. 52–53, 1975, was vital for artists who aimed to network internationally.

However, the lack of direct communication has led to many misunderstandings, which might be seen as a very practical reason why the performance artists started to put the photographic documentation together with a typewritten description of the event.

Petr Štembera. Narcissus, 1974. A4 paper, photograph, typewritten text, stamp, handwritten signature. New Reform Archive, collection Roger and Marie Hélène D’Hondt, Belgium. Image courtesy of Petr Štembera and Roger D’Hondt.

In the case of Štembera’s Narcissus, among many different manifestations of the documentation, we find the following format: an A4-sized sheet of paper featuring a selected photograph capturing the performance, along with a typewritten text, signed by the artist. More than any later prints, enlargements, or digitally converted scans from the negatives, these documents provide the most comprehensive view of the given work, as they reflect the artist’s own selection, unlike the myriad of film frames that someone captured during the event.

From Documentary Evidence to Socio-Cultural Object

Based on the developments in the field of history of photography, there are three levels of approaching the photographic documentation of performance art. While each has its historical justification, and at some point, the theoretical discussion may have favored one, it is also a matter of context, and each can still be encountered until now. First, the photograph is used as documentary evidence, functioning merely as a window to a captured reality and not intended to garner substantial attention. Second, the photograph is regarded as an aesthetic artifact, fostering an awareness of its intrinsic qualities, encompassing visual composition, framing, and authorship. Third and finally, the photograph is understood as a socio-cultural object that assumes distinct agencies based on particular geographic and historical coordinates.

In this perspective, which acknowledges the evolving materiality of photography in relation to its circulation, photography histories can move beyond the pictorial and singular.(Costanza Caraffa, ed., Photo Archives and the Photographic Memory of Art History, (Berlin: Deutscher Kunstverlag, 2011) or Julia Bärnighausen, Costanza Caraffa, Stefanie Klamm, Franka Schneider, and Petra Wodtke, eds., Photo-Objects: On the Materiality of Photographs and Photo Archives, (Edition Open Access, 2019), https://www.mprl-series.mpg.de/studies/12/2/index.html.) Thus, studying photography means untangling complex networks of agents, works, objects, and their various relationships and functions, always with a view to the use and “social lives” in specific times and places. As Elizabeth Edwards puts it, “an object cannot be fully understood at any single point in its existence but should be understood as belonging in a continuing process of production, exchange, usage, and meaning.”(Elizabeth Edwards and Janice Hart, “Introduction: Photographs as Objects,” in Photographs, Objects, Histories, eds. Elizabeth Edwards and Janice Hart, (London / New York: Routledge, 2004), p. 4.)

Reclaiming Materiality and Pursuing Concrete Uses

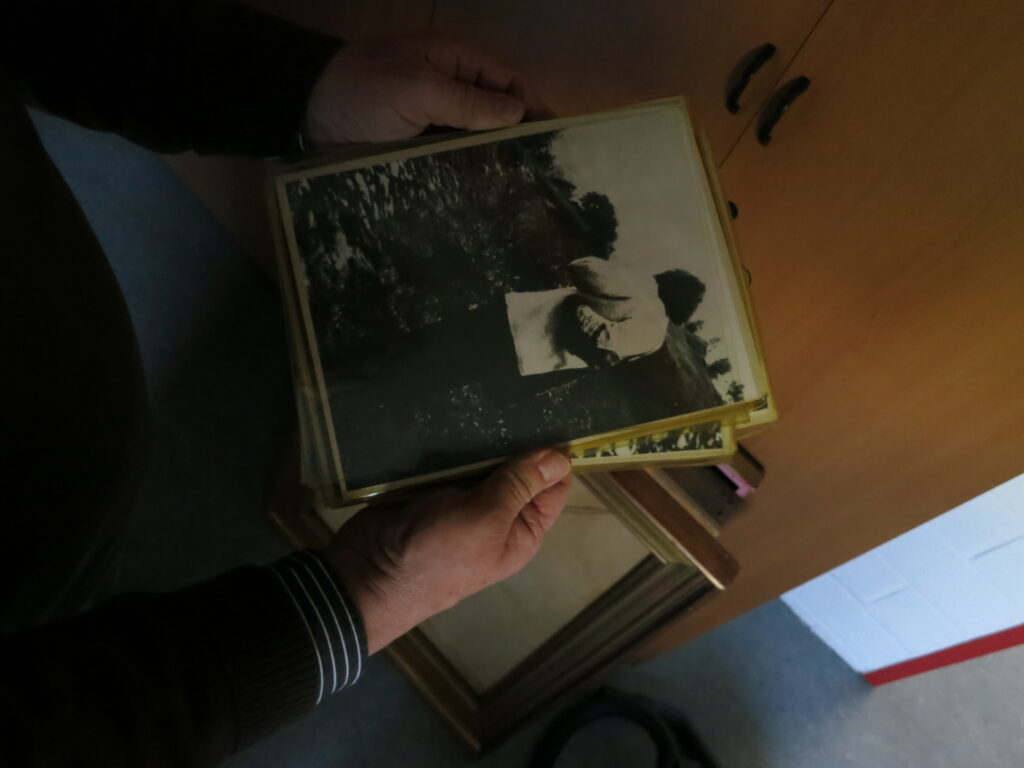

When considering the materiality of photographic documentation, a researcher focusing on 1970s Czech performance art (and fortunate enough to access archival materials) typically encounters a variety of black-and-white photographs differing in quality. These photographs may bear signatures or stamps, sometimes added retrospectively to authorize the prints. At times, negatives, 35mm or medium-format films, transparencies, or a few color slides are found in the archives. There may be a specific photograph chosen by the performance’s author or the photographer, often indicated by markings on the corresponding negative. Sometimes the photographer receives credit, other times they are known but uncredited due to being perceived as mere agents of the author’s original intent. Many situations are further complicated because these photographs were often taken spontaneously, with the assistance of friends, rather than as professional commissions. If, in general, the artists themselves have not paid much attention to the form of the photographs, whether due to practical reasons, lack of funds, or other considerations, it does not mean that it is not important in the retrospective analysis of those works. Sometimes, the form itself is telling, especially when it was the artist who chose a representative photograph of the event and signed either the photograph itself or a paper on which the photograph was glued or printed.

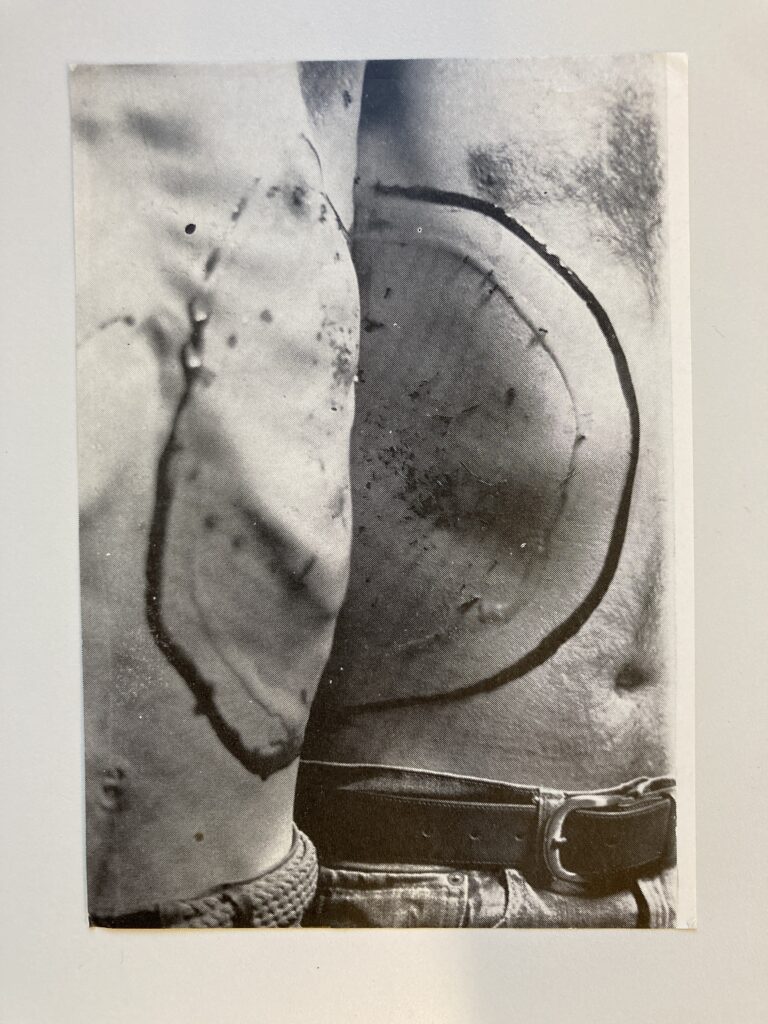

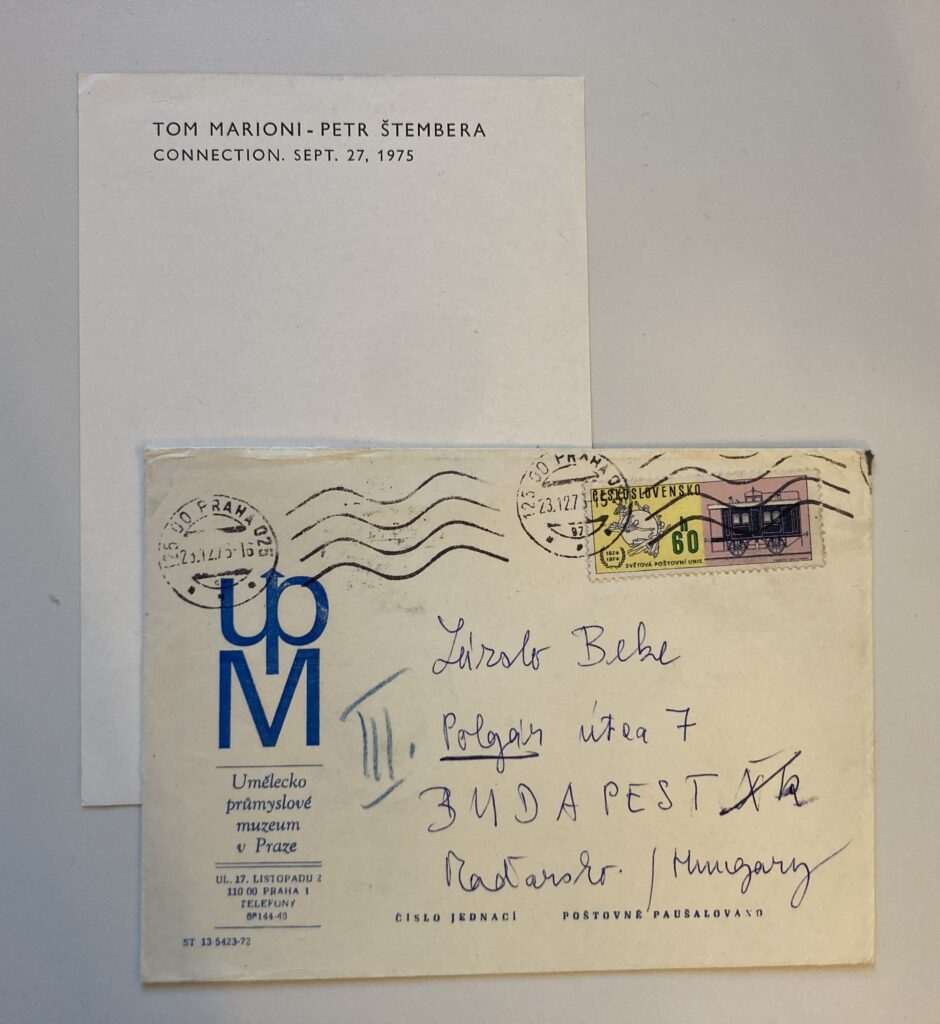

Petr Štembera and Tom Marioni. Connection, 1975. Photomechanical reproduction on a card. László Beke’s Archive, Museum of Fine Arts-KEMKI, Budapest. Image courtesy of Petr Štembera and Museum of Fine Arts-KEMKI.

Postcard in envelope sent by Petr Štembera to László Beke in 1975. László Beke’s Archive, Museum of Fine Arts-KEMKI, Budapest. Image courtesy of Petr Štembera and Museum of Fine Arts-KEMKI.

As previously mentioned, photographic documentation also encompasses photomechanical reproductions, and only in rare instances, the printing plate from which these reproductions were printed has been preserved. This was the case with Petr Štembera’s Connection, a joint performance realized in 1975 in Prague together with American performer Tom Marioni. Štembera addressed the discomfort associated with the meeting of the West and the East by creating a double circle on the performers’ bodies using two different types of condensed milk—white and cocoa, both available delicacies of the time—and placing hungry ants into this trap.(For more on this, see Buddeus, “Infiltrating the Art World,” p. 473.) From a selected photograph (a respective film field was marked on one of the film strips documenting the event) Štembera had a plate made and printed a postcard with a photomechanical reproduction. This shows that, in terms of documentation, he was primarily concerned with mass dissemination and with sending information about the work to as many people as possible. Although, in the conditions of Normalization-era Czechoslovakia, he likely had to risk encounters with the police when acquiring such printed material. One of the postcards printed from this plate that he subsequently mailed out in many copies may be found in László Beke’s correspondence. In this case, Štembera had to cut off three of the four white margins of the postcard so that it would fit in the envelope with the header of the Museum of Decorative Arts in Prague. His position as an employee at the institution allowed him to enjoy this advantage, which he said reduced the risk of the letter being intercepted.

Photography, exhibition copy

What then, does it mean when one discovers that within the long-awaited permanent exhibition “1939–2021: The End of the Black and White Era,” installed in 2023 in the National Gallery in Prague, all the above-indicated aspects are neglected and the photographic documentation of performance art is presented merely as a window into the events? The show aimed to complicate the prevailing narrative determining our understanding of Czech art from the Second World War to our present times, including the long era of Communist Party rule. Although the question of photographic documentation is a minor topic of this exhibition, the chosen form of presentation stimulates further discussion on the topic.

Jiří Kovanda, Contact (1977), and other Czech performance art documentation on display in the permanent exhibition “1939–2021: The End of the Black-and-White Era” at the National Gallery in Prague. Photograph by Hana Buddeus.

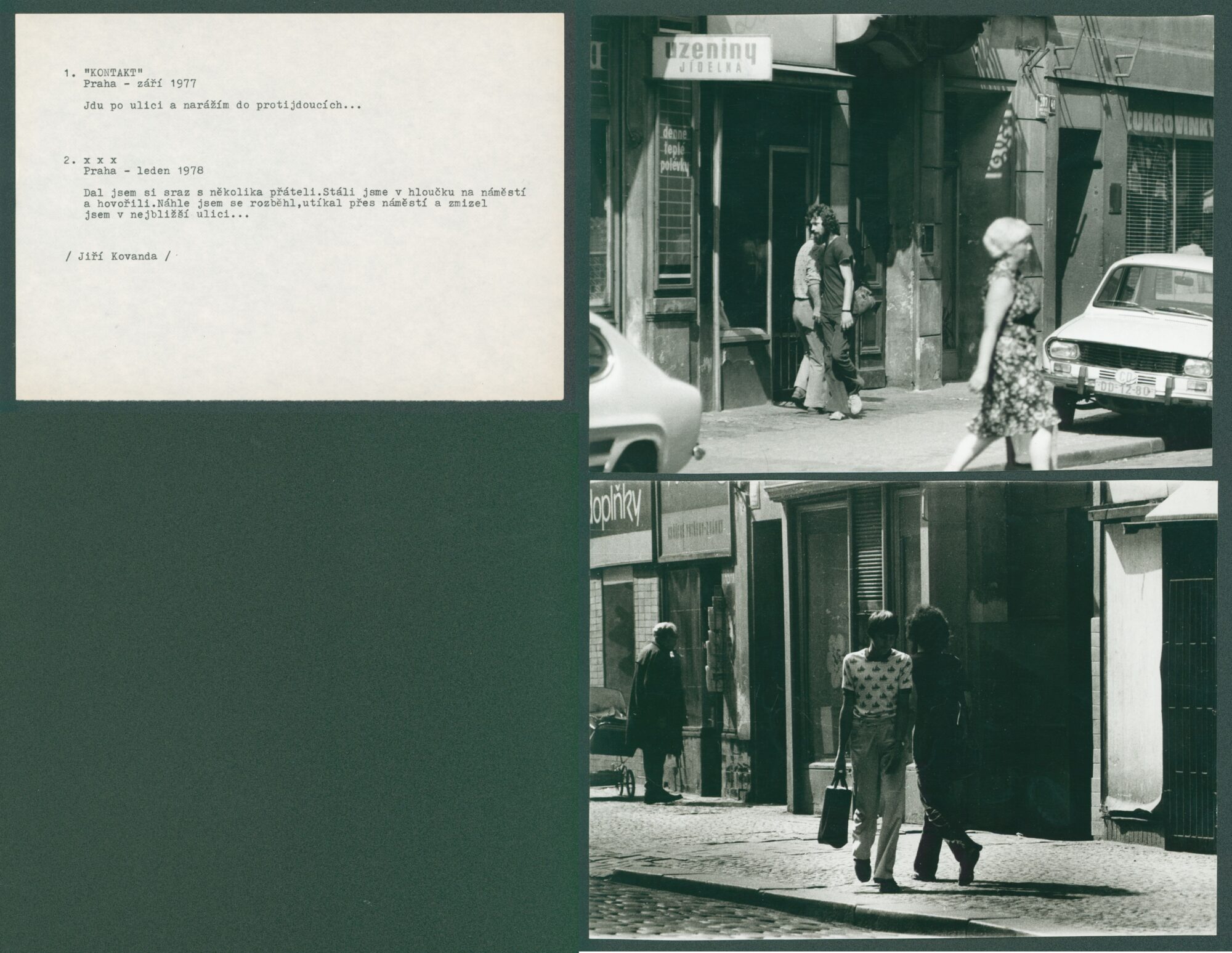

I assume that for reasons of protection, the curators could not have displayed the original photographs in the permanent exhibit, and they decided to present the photographic documentation in the form of digital prints glued on the wall. Moreover, only “photography, exhibition copy” has been indicated in the captions, without any reference to the real objects held in the collection. The same applies, for instance, to the display of Jiří Kovanda’s 1977 performance Contact, which consisted of walking the streets of Prague and bumping into passers-by, a work present in several collections worldwide. Even those “originals” that have become collection objects, often exist in multiple copies and may vary in the number of chosen photographs and/or their size.

For example, the copy of Contact owned by the Museum of Modern Art in New York shows just one square photograph, whereas the documentation of the same performance in Kontakt collection in Vienna includes four rectangular photographs documenting four interactions performed within the same event.(Jiří Kovanda’s Contact in the MoMA, Kontakt and Moravian Gallery in Brno collections is accessible online at https://moma.org/collection/works/178207; https://www.kontakt-collection.org/objects/325/contact-september-3rd-1977-prague-spalena-street-vodi?ctx=8c222155acd9f62319ccf152c78febbd6b1f0c0c&idx=8; https://sbirky.moravska-galerie.cz/dilo/CZE:MG.MGA_4283, accessed February 7, 2024. ) The latter, or the “original,” if we can speak in such categories, is on heavier A4 paper with a typewritten note and four photographs. It bears the traces of former use: it has been not only viewed but also touched. Kovanda recalls that together with other documentation in this format, he used to have such sheets in a folder, which served as his portfolio, and which he showed in private to people interested in his work. It wasn’t until the 1990s that he first exhibited such portfolio pages. Before that, he always created new prints from negatives for exhibition (and publication) purposes, which were shown separately, without being fixated on an A4 paper, and the text appeared only in the captions.(Personal meeting with Jiří Kovanda, March 1, 2024.) Such documentation of Contact can be found, for example, in the Moravian Gallery in Brno.(Interestingly, they have acquired it twice for their collections. It appears in the archive and collection of Jiří Valoch (an artist, curator, and important networker in the 1970s), which has recently also become part of the Moravian Gallery’s holdings and it is also held in the Gallery’s photography collection: https://sbirky.moravska-galerie.cz/dilo/CZE:MG.MGA_4283, accessed February 17, 2024. )

Jiří Kovanda. Contact, 1977. Two black and white photographs, typewritten text on paper. Archive and Collection of Jiří Valoch, Moravian Gallery in Brno. Image courtesy of Jiří Kovanda and the Moravian Gallery in Brno.

The captions accompanying the exhibition copies of Contact on display at the National Gallery in Prague do not provide any details about the material or size of the original. To clarify, I viewed the six photographs held in the collection, which actually appear to be authorized prints. On the reverse, there is a stamp from the Photographic Studio of the National Gallery with the note “supplied negative,” and Kovanda’s signature. The collection curator, Monika Čejková, states that the photographs likely date from the 1990s when the then-permanent exhibition was prepared.(E-mail correspondence with Monika Čejková.) Kovanda has confirmed that he may have lent the negatives to the National Gallery to make prints of their own. The point here is not to criticize this acquisition but to discuss the significance of different formats that goes hand in hand with the specific uses and circulation, so characteristic of photographic documentation of these performances. Because, to recall Rezek again, the document “itself constitutes the meaning.”

In the context of photography histories, attention to materiality is always accompanied by consideration of the intended use of each photograph. There is a certain paradox unique to photography, highlighted by Olivier Lugon: “Before photography, any image had its own permanent scale set by the time of its production,” whereas with the advent of photography, each reproduction may show the same image, yet it might have a significantly different impact depending on its specific use. This paradox underscores the importance of factors such as “planned function, audience, and mode of display,”(Olivier Lugon, “Photography and Scale: Projection, Exhibition, Collection,” Art History 38, no. 2 (April 2015), pp. 387–388.) which inevitably influence the size, number, and quality of prints, the photographic documentation of performance art included. Photography is not just a carrier of information or a language used for its universally acknowledged credibility and veracity, allowing us to communicate, nor is it simply a unique, signed artwork. It can easily travel; it can be bought, scanned, printed, or glued to the wall. It is definitely something produced—to use Timothy J. Clark’s description of an artwork—“a material and historical object, tugged and shaped by a field of conflicting voices, practices, wishes, perspectives, and powers.”(Timothy J. Clark, “Art History in an Age of Image-Machines,” EurAmerica 38, no. 1 (March 2008): pp. 3–4.)

It might seem paradoxical that it was my research in the so-called dematerialized art, that brought me to thinking about the material aspects of photography. In most cases, these documents were primarily created to convey the represented ideas and events. Yet, my aim was to show that gaining an understanding of their material characteristics and examining their social trajectories can shed light on the nature and distinctive operational mode of performance art and helps to understand the mechanisms of both East-West and East-East artistic transfers in their complexity.

This article is part of a Special Issue on Regional Resonances. You can read other articles from this Special Issue published on ARTMargins Online below: