Thinking Pictures: Conceptual Art from Moscow and the Baltics

Although fewer than two decades have passed since its opening, the Kumu Art Museum, located in Estonia’s capital city Tallinn, is widely acknowledged for its critical exhibitions that often highlight the nation’s traumatic past. Earlier this year, the museum showed Thinking Pictures: Conceptual Art from Moscow and the Baltics, curated by Anu Allas (professor at the Institute of Art History and Visual Culture of the Estonian Academy of Arts), Liisa Kaljula (curator at the Kumu Art Museum), and Jane A. Sharp (curator at the Zimmerli Art Museum and professor in the Department of Art History at Rutgers University, New Jersey, USA). The exhibition focused on the dialogue between conceptual art from Moscow and the Baltic countries in the 1970s and 1980s—when Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania were still part of the Soviet Union—and on how this dialogue might affect the way we think about the phenomenon known as “Moscow Conceptualism,” a now globally recognized tendency whose best-known representatives include Ilya Kabakov, Viktor Pivovarov, Vitaly Komar & Alexander Melamid, Erik Bulatov, and Andrei Monastyrski.(The Kumu exhibition was a development of an earlier show curated by Jane A. Sharp, entitled Thinking Pictures: Moscow Conceptual Art from the Norton and Nancy Dodge Collection that was shown in 2016 at the Zimmerli Art Museum at Rutgers State University. See: https://zimmerli.emuseum.com/exhibitions/32/thinking-pictures-moscow-conceptual-art-from-the-norton-and)

The opening of Thinking Pictures was scheduled for early March 2022, just a few days after the beginning of the Russian invasion of Ukraine. These horrifying political events put the show’s curators in a difficult position: should they open the exhibition as planned, or cancel it in solidarity with Ukraine? They finally decided to open the show, but without any artwork visible. The works were then gradually installed over the following few weeks until all of the works were visible in the exhibition space. To see the (almost) empty exhibition was an intense and ultimately rewarding experience, and the curators’ decision was an impressive act of critical curatorship that is cognizant of the way in which art is impacted by events beyond its control.

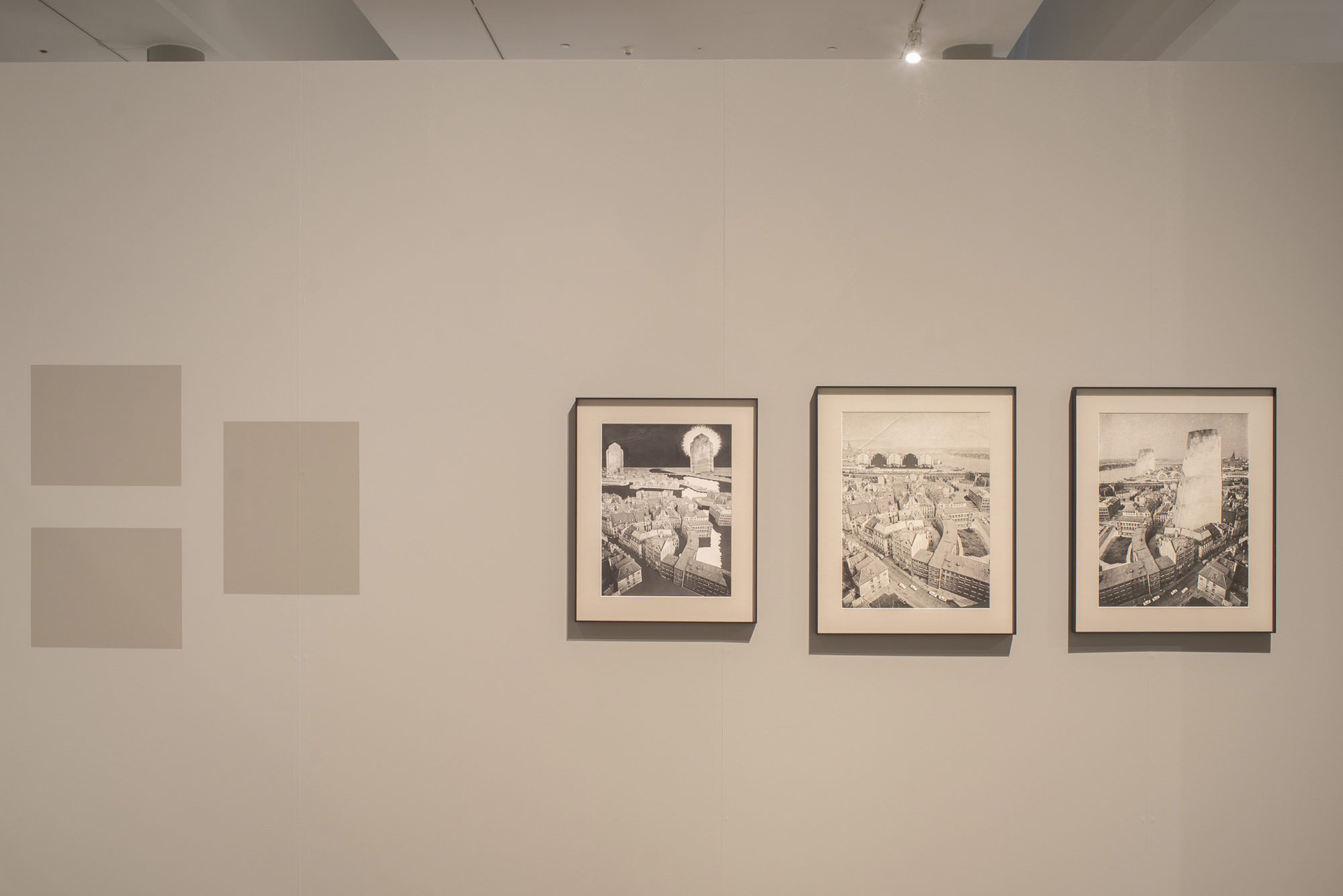

Thinking Pictures: Conceptual Art from Moscow and the Baltics, exhibition view. Photo by Paco Ulman, courtesy of Kumu Art Museum.

The curatorial concept is explained in more detail in the exhibition catalog.(Thinking Pictures. Conceptual Art from Moscow and the Baltics. Eds. Anu Allas, Liisa Kaljula, Jane A. Sharp. Tallinn: Kumu Art Museum, 2022.) As stated in the introduction, the project ambitiously aimed to “broaden the understanding of conceptual art created in the late Soviet environment, to break through the narrow confines of national art history narratives, and to disrupt the hierarchy between the center and the periphery (…).”(Allas, “Introduction,” Ibid, 8.) The curators used the exhibition as a tool for writing a history of conceptual art of the Baltic region. Relying on Piotr Piotrowski’s concept of horizontal art history, they considered the phenomenon of Moscow Conceptualism as hegemonic and hierarchical within the discourse of East European conceptual art—due to the global acknowledgment of the term, as well as its inherent unifying art historical narrative, written from the center of the former Eastern Bloc, Moscow. Therefore, they decided to use diverse narratives, told from their position located in the Baltics, on the edge of the former Soviet Union.

The exhibition was well-grounded in Piotrowski’s ideas on how to write East European art history, adopting his approach that included transnationality, critical revision, hybridization, pluralization, heterogeneity, discursivity, and deconstruction of the center.(Anu Allas was a co-editor of the publication Globalizing East European Art Histories, which emerged from a conference in Lublin, Poland, convened by Piotr Piotrowski in 2014. See Globalizing East European Art Histories: Past and Present. eds. Beata Hock, Anu Allas. New York/London: Routledge, 2018.) Based on the artistic material from Soviet Russia, Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania, the exhibition manifested the writing of art history which is “polyphonic, multi-dimensional, devoid of geographic hierarchies.”(Piotr Piotrowski, “1989: The Spatial Turn,” in Piotr Piotrwowski, Art and Democracy in Post-Communist Europe. (London: Reaktion Books, 2012), 39.) This diversified nature was emphasized by the selection of various artists from different environments or contexts, using variable artistic media and approaches.

Thinking Pictures consisted of twelve thematic groups designed to express the heterogenous, plural, or fluid character of conceptual art in late-Soviet Moscow and the Baltics. Each of the groups comprised works by conceptual artists from Moscow, as well as Soviet Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania, with all the works being displayed with equal status, and none held in any way superior to the others. Each topic was labeled and briefly explained by the wall texts. Considering the limitations of the exhibition space, there were perhaps too many topics covered by the show, which could result in the viewer’s confusion. However, this also confirmed the discursive body of the exhibition with a multi-layered, fluid think tank. Several topics intertwine with one another, and, as stated in the catalog, the show is divided into three main blocks.(Allas, “Introduction,” 11.)

The first section comprised themes including The Soviet Universe, Sots Art, City Interventions, and Travelling into the Green, all focusing on various aspects of everyday Soviet life. For instance, one can witness the motif of social isolation in two paintings from Viktor Pivovarov’s series Project for a Lonely Man (1975). These flat paintings, each combining an image with a word, recall posters in the field of graphic arts. The depiction of a small Soviet flat’s floor plan or a simple room with ordinary things that have bizarre labels attached to them is reminiscent of Soviet instruction manuals. Meanwhile, the painting My Passport (1979) by Latvian artist Bruno Vasiļevskis captured the Soviet passport in precise, photorealistic detail. This display of such a travel document given the travel restrictions for citizens of the USSR evokes the harshness of Soviet reality. Another photorealistic work, Victory’s Interior (1984-1985) by Lithuanian Romanas Vilkauskas, shows a wall covered with old, yellowed newspapers. At the center of the wall, there is a photograph of a smiling Stalin, highlighting the contradiction between the shiny, optimistic state propaganda and the actual poverty of the Soviet people.

The ironic representation of Soviet propaganda and visual culture more generally dominates the works by the Russian artistic duo Vitaly Komar and Alexander Melamid. Both are key figures in the conceptual tendency of Sots Art. Their work Our Goal is Communism! (1972) uses a well-known Soviet propaganda slogan that the artists signed. By appropriating officialdom’s visual language, Komar & Melamid attempt to disrupt the seriousness of Soviet iconography. Iconic Soviet symbols were also creatively used by Estonian artist Leonhard Lapin. His four silkscreens Stalinism and Abstractionism, Stalinism and Satanism, Suprematism and Socialism, and Surrealism and Socialism (1990) show how Lapin transformed these emblems into pure geometric forms in an effort to undermine the authority of the state.

The Kumu exhibition also pointed to the city and to nature as important sources of inspiration for Soviet conceptualist artists. The series of photomontages Vilnius Notebook I. (1988) by Lithuanian Mindaugas Navakas, for instance, depicts typical Soviet apartment blocks altered with various monumental designs that disrupt the monotony of the banal Soviet reality. Similarly, the Latvian artist group The Emissionists (Pollucionisti), in their photomontage series Bizarred Riga (1978), comments ironically and critically on the problems and the failures of the Soviet urban environment. Taking a different approach, other artists chose to abandon the urban environment altogether. Thus, the performance Action 33: The Russian World (1985)—a phrase that rings very differently to us today than it did back then—by Collective Actions shows group members in a wintery landscape locked in observation. Rather than offering a strong narrative, Collective Actions is interested in the process of observation itself, and in the relationship between the audience and the performers. This is also reflected in the happening Conceptual Games (1978) by Lithuanian artists Kaze Zimblytė, Gediminas Karalius, Petras Mazuras, and Vladas Vildžiunas, who created improvised site-specific installations on the outskirts of the Lithuanian capital Vilnius.

The show’s second part united the themes of Text and Image; Fundamental Lexicons: Circle, Square, Triangle; and Objective Art, and expressed the Soviet conceptual artists’ affinity for working with words, texts, books, poetry, geometric forms, and the ideas of the Russian avant-garde. The exhibition included examples of visual poetry, such as Raul Meel’s subtle series of drawings created on a typewriter, or Dmitri Prigov’s spiral text collages. Some works used various elements of the Soviet world as a universal visual language, reflecting the influence of French structuralism and its use of language as a model for understanding reality.

Thinking Pictures: Conceptual Art from Moscow and the Baltics, exhibition view. Photo by Paco Ulman, courtesy of Kumu Art Museum.

Leonhard Lapin’s Self-Portrait (1979) shows the artist’s head in profile and in red, reminding the viewer of familiar portraits of Lenin. Meanwhile, Russian artist Alexander Kosolapov, in the photographic series Gesticulations. Language of the Masses (1978-1979) imitates the strict gestures and expressions of members of the Soviet armed forces, and Russian artist Leonid Sokov’s Project to Construct Glasses for Every Soviet Citizen (1975) is a pair of carved brown wooden spectacles with lenses in the shape of a red communist star, which satirically offers a way to see a bright, happy Soviet reality.

Thinking Pictures: Conceptual Art from Moscow and the Baltics, exhibition view. Photo by Paco Ulman, courtesy of Kumu Art Museum.

Soviet conceptual artists often worked with geometric shapes reminiscent of the Russian avant-garde, and with Kazimir Malevich’s idea of art as a spiritual substance. The exhibition included several examples of this trend, such as Latvian Sirje Runge’s series Geometry (1976-1977) in which she uses basic geometric structures and colors to create dynamic compositions and illusory spaces. Likewise, Estonian artist Silver Vahtre, in the series Blue Skies (1983), transforms banal landscapes into energetic spiritual images through the use of elementary geometric forms. “Thinking Pictures” also included Komar and Melamid’s ironic deconstruction of avant-garde symbols in the project Circle, Square, Triangle (1975) where the artist duo presented Suprematist geometric designs as commodified home decorations.

The last section of the exhibition focused on the themes of Picture as Critique, Body and Space, Fading Images, and Existential Questions. Compared with previous sections, this one dealt with more theoretical, philosophical, or even existential problems, including the artist’s identity. In his Self-Portrait in a Vermeer Painting (1985), for example, Latvian artist Miervaldis Polis tried to join the history of Western art by painting himself into a reproduction of a famous work by Vermeer. Two black and white photographs from the series Signatures (1976) by Leonid Sokov capture a typographical sign with the artist’s surname. While the first photo depicts the artist’s signature being thrown out in the yard like a piece of trash, the second one shows that the typographical object is already being taken away by an excavator. The artist’s name is also the subject of Composition (1960s-1970s) by Lithuanian Kaze Zimblytė, who collaged newspaper scraps to spell her own name.

Unofficial neo-avant-garde artists in Eastern Europe regularly faced harassment by the state; they were frequently interrogated by secret agents, their exhibitions were closed, and their art often remained invisible to a larger audience. These circumstances were reflected in several artworks in the show, including a series of photographic nudes by Lithuanian artist Violeta Bubelytė (1982-1985) that captures a naked female body in a fluid space between reality and abstraction. Moscow conceptualist Irina Nakhova, for her part, explores the fragile relations between the body and its environment. Her photograph Room no. 3 (1986) shows a figure sitting in an interior where all other objects are wrapped up. A work by second-generation Moscow conceptualist Vadim Zakharov, V. A. Zakharov Conducts an Information Exchange with the Sun (1978), shows the photographic documentation of the artist’s performance in the middle of an ensemble of gray Socialist housing blocks. Using a small pocket mirror, Zakharov creates a reflection of the sun, and thereby he seems to be holding a bright beam of light in his hand. One can see this gesture as a symbolic attempt to disrupt the grayness of Soviet everyday life or the artist’s exit from the closed world of the Iron Curtain.

Basic existential questions are also raised in Viktor Pivovarov’s series Face (1975), which shows the portrait of a woman whose face we cannot fully see because it is covered by the representation of her thoughts. As the series progresses, the portrait gradually falls apart until it finally disappears completely. The blue background may be suggestive of the artist’s “blue” mood. Similarly, Lithuanian artist Kaze Zimblytė, in the paintings Moods (1985), expresses her dark feelings. The black rectangles surrounded by monochromatic areas of color recall Mark Rothko’s method of expressing emotions through color in painting. Finally, Latvian painter Bruno Vasiļevskis signals his immediate surroundings in his photorealist paintings Books (1984) and White Wall (1984) whose titles are a precise reflection of the works’ content.

Just like the exhibition, the catalog is also heterogeneous and discursive in its nature. The Estonian-English publication brings various, pluralistic perspectives on the topic of the late-Soviet conceptual art, with four articles focused on issues relating to the exhibition. The first one, “Inside the Picture: Moscow Conceptualism Revisited,” by Jane A. Sharp, provides the author’s analyses of Moscow Conceptualism and some of its key works; Liisa Kaljula’s article “Baltic Sots Art: Appropriation Art from the Western Periphery,” acquaints us with the tendency of Sots Art in the Baltic countries; Janis Taurens interprets two Latvian artistic groups: the Workshop for the Restoration of Unfelt Feelings (NSRD) and the Emissionists, as well as Latvian conceptual art through the lens of postcolonial theory; and Skaidra Trilupaitytė outlines the situation of the late Soviet era and contemporary art institutions in Lithuanian art in her text, “Lithuanian Semi-non-conformism, ‘Classical’ Rebel Art and Contemporary Art Institutional Quandaries.”

One can recognize three main aspects which make the exhibition Thinking Pictures a significant contribution to contemporary art theory and practice, and especially to the field of East European art history. Firstly, it showed the possible ways of creating art historical narratives and writing regional art history. The second point was a notion of the exhibition as a fluid, flexible and heterogeneous structure, which offers multiple voices and perspectives on the subject matter, and asks more questions than it gives straight answers. Thinking Pictures included numerous artworks and artists; however, one notable absence was the important Estonian artist Ülo Sooster, a close associate of Ilya Kabakov’s whose work provides a key link between the Russian and the Estonian unofficial art scene.

The last distinguished feature was the implementation of critical institutional and curatorial practices. Since the exhibition opened during the first weeks of the Russian war in Ukraine, the curators decided to open an empty exhibition, gradually filling it up with artworks as a sign of their disagreement with the war. All of this resonates with the notions of “critical curating,” a form of curatorial activism, with curators expanding their usual role;(Marie Fraser and Alice Jim Wai Ming, “Introduction. What is Critical Curating?,” RACAR: Revue d’art Canadienne/Canadian Art Review 43/2 (2018) 5-10.) and “post-representational curating,” which is what art historian Nora Sternfeld describes as “the conscious involvement in public debates in solidarity with existing social struggles.”(Nora Sternfeld, “Involvements – A short introduction to curating between entanglement and solidarity,” Mustekala, 14. 10. 2013. https://mustekala.info/teemanumerot/kuratointi-3-13/involvements-a-short-introduction-to-curating-between-entanglement-and-solidarity/ (accessed January 29, 2023)) Similarly, one can recognize in the Kumu exhibition Piotr Piotrowski’s theory of the “critical museum,” which he considered the ideal form of a museum for contemporary society. It is such a museum that reacts to the ongoing changes or challenges of the present world, is aware of its social responsibility, and uses its cultural authority and space to take an active role towards the public, helping to protect human rights and democratic processes.(Katarzyna Murawska-Muthesius and Piotr Piotrowski, “Introduction,” in From Museum Critique to the Critical Museum. eds. Katarzyna Murawska-Muthesius and Piotr Piotrowski. (Vermont: Ashgate, 2015), 1.) And this is precisely what Thinking Pictures has accomplished.

Thinking Pictures: Conceptual Art from Moscow and the Baltics, exhibition view. Photo by Paco Ulman, courtesy of Kumu Art Museum.