The Wayland Rudd Collection and the Network of Mutuality: An Interview with Yevgeniy Fiks

In this interview, artist Yevgeniy Fiks speaks with art historian and curator Ksenia Nouril about The Wayland Rudd Collection, the artist’s ongoing project that brings together a wide range of Soviet images depicting Africans and African Americans. Established as a collaborative project that incorporates contemporary interventions, the Rudd Collection nuances what is typically projected as a monolithic Soviet culture while also enhancing our understanding of race in and beyond contemporary Russian society.

Ksenia Nouril: What is The Wayland Rudd Collection?

Yevgeniy Fiks: The Wayland Rudd Collection is a participatory, conceptual art project at the center of which is an archive of by now over 300 digitized images of Soviet-era depictions of Africans and African Americans. The collection spans the entire Soviet period from the 1920s to the 1980s, with images ranging from racially problematic New Economic Policy advertisements to anti-racism and internationalism propaganda materials to private, intimate portraits. I assembled most of the archival images between 2010 and 2012, then “activated” them by enlisting others – artists and academics – to reflect on this complicated and contradictory body of historical images, reckoning with the history of the twentieth century, specifically the legacies of Soviet art. The Wayland Rudd Collection is an ongoing work, and a book dedicated to the project will be published by Ugly Duckling Presse in late 2020.

KN: What made you begin collecting these images?

YF: The Wayland Rudd Collection began in Summer 2010. I had just read the essay “W. E. B. Du Bois and Soviet Communism: The Black Flame as Socialist Realism” by Lily Wiatrowski Phillips in the collected volume Socialist Realism without Shores. It’s about Du Bois’s The Black Flame trilogy and his other late writings and their relationship to the Soviet literary canon. I think this was my first exposure to scholarship on the connection been twentieth-century Soviet and African-American aesthetics as part of a broader idea of communist aesthetics, traversing national borders and ethnic predicaments.

I immediately saw connections between this scholarship and my pervious art projects, such as Communist Party USA, a series of portraits of today’s members of the American Communist party that I made in 2005-2007. While working on these portraits and learning more about the history of the Communist Party USA (CPUSA), the prominent presence of the African-American story within the larger story of American communist activism in the twentieth century was absolutely clear to me. By the way, the story of Du Bois joining the CPUSA at age 93 was part of my project Communist Guide to New York City (2007), which documented sites of American communism in Manhattan.

Around 2008, my work changed. I felt the need to complicate my relationship with the Soviet Union, specifically its positions on race, gender, and sexuality. I wanted to take apart the purported universality of Soviet and communist narratives. And so The Wayland Rudd Collection was born.

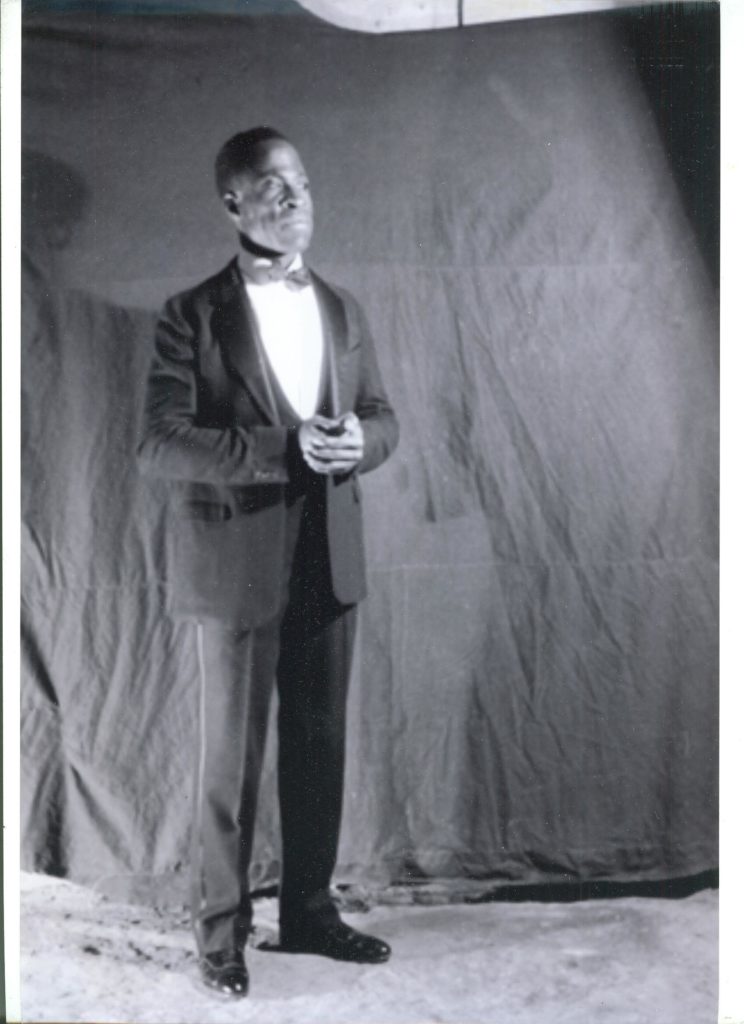

American Actor Wayland Rudd in the Role of Singer Johnston on Stage of V. Meyerhold’s Theater. Image courtesy of the Russian State Film and Photo Archive.

KN: What is your relationship to Wayland Rudd (1900-1952), the African-American actor who left the United States for the Soviet Union in 1932 and remained there until death?

YF: I wanted to name my fictitious “collection” after a person, to personify it as a body of images. I specifically wanted to name my project after a Black person in the Soviet Union whose visual image was present in Soviet visual culture.

While I was searching for and collecting images, I was reading a lot of stories about African-American expatriates in the Soviet Union – about their experiences in the Soviet Union, about their relationship to America before and during their (self-) imposed exile. There is a lot written on the subject, including personal memoirs, including one by engineer Robert Robinson. One of the stories was about a group of African-American intelligentsia who came to the Soviet Union in 1932 to work on the Soviet movie BIack and White, which actually was never made. Among this group was a young African-American actor Wayland Rudd. Most of the group returned to the United States, including poet Langston Hughes, but Rudd remained.

Rudd is an African-American Soviet actor who has been largely forgotten and who was never as popular as the larger-than-life actor and singer Paul Robeson, who was a household name in the Soviet Union. But I think Rudd, more than Robeson, embodied the real bond between the African-American story and the Soviet story. Rudd stayed in the Soviet Union until the end of his life, including through the war years, which means a lot. I wanted Rudd to be remembered somehow. I don’t have a direct personal connection to him, apart from seeing him as a fellow Soviet and a believer in the Soviet experiment, whom I’m was compelled to commemorate as a type of Soviet kaddish. There also happens to be several images of Rudd himself in The Wayland Rudd Collection, including portraits of him and propaganda posters for which he served as a model.

KN: So, is it fair to say that The Wayland Rudd Collection is a parafictional project? I am using the term “parafiction” as defined by scholar Carrie Lambert-Beatty as something “related to but not quite a member of the category of fiction…in which real and/or imaginary personages and stories intersect with the world as it is being lived.”(Carrie Lambert-Beatty, “Make-Believe: Parafiction and Plausibility,” October 129 (Summer 2009): 54.) In this way, the parafictional achieves the degree of trust typically reserved only for the real.

YF: Yes, the Rudd Collection is not a real collection nor is it a real archive. It’s my art project. Rudd didn’t collect these images, so attaching his name to this project is a conceptual gesture of commemoration, acknowledgment, and respect. Some of the items in the collection are original objects while others are either facsimiles or merely exist as digital files. At the same time, the collection is grounded in research. All images in the collection are historical – created by real Soviet artists of the time. I did not create or manipulate any of the images. However, by naming the project The Wayland Rudd Collection and making it sound legitimate as well as seeing others treating it as such – I often get inquiries from scholars – it, perhaps, becomes parafunctional.

KN: When it came to race relations, the Soviet Union saw itself as superior to the United States. This was expressed in Soviet propaganda, including the 1936 film Circus that tells the story of a white American circus performer who finds acceptance for herself and her mixed-race baby in the USSR. However, this was not always the case. This fraught juxtaposition between the benevolent Soviets and racist Americans is also seen in The Wayland Rudd Collection. Could you talk about how race relations are depicted in a few keys work from the collection? How did that depiction change over the course of the Soviet Union, especially in relation to its development of Socialist Realism?

YF: Most images in The Wayland Rudd Collection were often very crude in their rhetoric because they were made as propaganda, which circulated in the Soviet media. The most common tropes are depictions of proletarian internationalism, usually represented by groups of different races shoulder-to-shoulder in a struggle against oppression, looking towards a better future. These include images of dignified fighters breaking chains of oppression and images of suffering under imperialist and colonial oppression.

There are also themes that perhaps can only be noticed through our contemporary view. For instance, the dominance of Slavic-looking figures even when the intention is to depict equality or the struggle for equality, such as in a poster by E. Artsrunyan. The blue-and-white banner in the background says, “Let the sky be clear!” while the red text striking out of the mushroom cloud in the foreground says “Ban!” The ethnic and racial makeup of the Soviet Union was extremely diverse. However, in the context of international visual representation of peoples from different countries and nations, the USSR would always be represented by a Slavic-looking man (in this image with the hammer and sickle on his chest) leading peoples of other nations.

Similarly in an earlier poster by Gustav Klutsis, a large Caucasian/Slavic-looking worker holds a red banner that says, “The USSR Is the Shock Brigade of the World Proletariat,” while the text along the pole says, “Proletarians of the World, Defend your Socialist Homeland.” The faces of other non-Caucasian peoples representing other nations and races are looking up at the Caucasian giant, who is the communist leader of the international working class.

And in another poster from the 1960s by Viktor Koretsky and Yevegeny Abezgus, a white hand is placed more prominently among a group of brotherly hands of equals, despite a message that states, “Communism affirms peace, labor, freedom, equality, brotherhood, happiness on the entire Earth!”

KN: What are some of the other themes that emerge from these images?

YF: Another strange theme is the proliferation of grotesque racial stereotyping. This occurs when the depicted person of color is perceived as an ideological enemy of the Soviet Union, such as in the collaborative Kukrynisky’s poster that reads “’Civilization’ the British Style.” The display of racist stereotyping of this image produced by the supposedly Soviet internationalist artists and commissioned by the supposedly internationalist state is striking. It looks like not a single trace of anti-racism is left in Soviet propaganda art if the African in the picture is the enemy of Communism. Racist depictions are instrumentalized in Soviet propaganda and are seemingly okay if it’s politically advantageous.

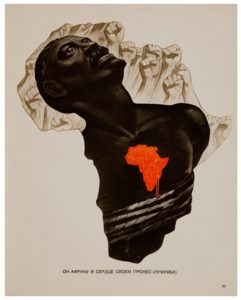

Such images of stereotyping are in stark contrast to images of absolute dignity, such as Viktor Koretsky’s homage to Patrice Lumumba (1925-1961), a Congolese politician and independence leader who served as the first prime minister of the independent Democratic Republic of the Congo, and played a crucial role in the transformation of Congo from a Belgium colony to an independent nation before being assassinated in 1961.

Viktor Borisovich Koretsky, He Carried Africa in His Heart (Lumumba), 1962. © 2020 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / UPRAVIS, Moscow. Image courtesy of the Ne boltai! Collection.

KN: How do works in the Rudd Collection address the intersection of gender and race?

YF: Another point of note is the visible lack of images of women as compared to those of men. Although there are images of three female figures of different races representing internationalism and friendship of people, women are most often portrayed in the context of motherhood or objects of liberation as opposed to activists and leaders of independence struggle.

KN: How else does the Rudd Collection reflect Soviet society?

YF: Another theme that appears starting in the 1970s is what I would call the “depoliticization” of Soviet propaganda. This is when the ideological rhetoric becomes less communist and more universalist, and no longer driven by the words of Lenin, Stalin, and other Soviet leaders.

In the late-Soviet era, Soviet visual propaganda began to appear more aestheticized. As a result, political messages became less direct. As if a commission to produce a propaganda poster became an occasion for the late-Soviet artist to experiment with artistic form or create “art for art’s sake.” This is true in V. Karakashev’s poster “Peace to the World” realized in the Russian “lubok” folk-art style. The artist employs the metaphor of weather (sun and clouds), rather than using literal political imagery of geopolitical confrontations and threat of war.

KN: What is the effect of contemporary interventions into the Rudd Collection? How have they reframed issues of race and racism in the USSR and in Russia for contemporary audiences?

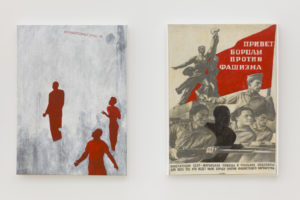

Dread Scott, Greetings to the Fighters Against Fascism and A Song of Peace: Paul Robeson in the Pickskills, 2014. Mixed-media installation. Image courtesy of the artist. Photograph by Etienne Frossard.

YF: Since the beginning of this project, it has always been important for me to enlist others, including contemporary artists and scholars coming from diverse American, post-colonial, and post-Soviet perspectives because I felt that the legacy of these historical Soviet images were just too complex for me to properly handle on my own. Because of the weight of this material, I enlisted contemporary artists, including Ivan Brazhkin, Maria Buyondo, Natalia Pershina-Yakimanskaya (Gluklya), Dread Scott, and Haim Sokol, to intervene in the collection, responding to its objects. While the work of these artists may be disparate, they are united by interests in multiculturalism, American and Soviet history, revolutionary art, and race representations. Their works were first exhibited by Winkleman Gallery in New York in Spring 2014 and later the same year at First Floor Gallery in Harare, Zimbabwe.

One of the major themes these artists addressed through the collection was mourning solidarity. For example, the Moscow-based artist Ivan Brazhkin contributed a video work called Tito Romalio (2014) Born in 1951, Romalio was a Black Brazilian-Soviet child star, who became famous in the 1960s for his roles in Soviet propaganda films geared toward children and teens about internationalism and friendship between peoples of different races. Romalio was murdered in 2010 by a supermarket security guard in St. Petersburg. His murder was captured by security camera footage, which is interwoven in Brazhkin’s video with incongruously idealistic scenes from Romalio’s 1960s Soviet films.

Personal history was another important theme explored by these artists. New York-based artist Maria Buyondo’s photo-video work Pushkin, Winter Morning (2011) is a reflection on the artist’s personal encounters growing up as a bi-racial person in the Soviet era. Buyondo uses photography and video to recite a poem by Alexander Pushkin that the artist had to memorize in the first grade in Moscow in 1989. In the video, Buyondo fails to get the lines right and is agonizingly forced to start over again repeatedly.

KN: Could you talk about your forthcoming book The Wayland Rudd Collection: Exploring Racial Imaginaries in Soviet Visual Culture? How did you approach translating this collection of three-dimensional objects into a book?

YF: Because The Wayland Rudd Collection is so expansive, the book is limited to only two-dimensional images that circulated in the mass media, like propaganda posters, stamps, and book illustrations. The book will include hundreds of these images and several texts, including two of my own.

For example, Raquel Greene writes about the representation of black bodies in Soviet children book illustration. Maxim Matusevich looks at Paul Robeson and the Soviet context, and Christina Kiaer examines the representation of African Americans in works by Aleksandr Deineka. Jonathan Shandell is writing about Rudd’s early career as an actor in the United States prior to his move to the Soviet Union.

KN: What are your hopes for the project as we continue to face racial inequality and social injustice in the United States and globally?

YF: Speaking historically, I would like to see the forthcoming book as a step in having the Soviet legacy of militant anti-racism acknowledged in the United States – not only in artistic and intellectual circles but also within mainstream public knowledge. The fact that the Soviet Union stood unequivocally on the right side of history in the twentieth century as far as its stance against anti-Black racism internationally is something that must be made known. I say this with full knowledge and acknowledgement of the Soviet Union’s own problematic record of human rights abuses, including the treatment of its own ethnic and minority groups.

From an internationalist or universalist perspective, The Wayland Rudd Collection shows that racism is never just a national issue, an embarrassing secret that a particular nation state could try to hide and sweep under the rug. It testifies to the fact that racism in the United States or colonial oppression in Africa are international, global issues, and also highlights national or local expressions of injustice on the global stage, where they affect humanity at large. The Wayland Rudd Collection is about this mutual network that traverses national borders.

This article is part of the Special Issue Art and Race in Contemporary Central and Eastern Europe. You can find links to the other articles in the special issue below: