Color–blind and Color–coded Racism: Angela Davis, the New Left in Hungary, and “Acting Images”

Race is a social construct based on images of “otherness.” In Eastern Europe, where self–identification relies on “whiteness”(See also: “Historicizing ‘Whiteness’ in Eastern Europe and Russia,” Socialism Goes Global, last modified June 26, 2010, http://socialismgoesglobal.exeter.ac.uk/conferences/.) as a construct, systemic racism along color–codes has been, and still is, experienced as irrelevant, “far away,” and without any actual real impact on society.(Ian Lew, Nikolay Zakharov, “Race and Racism in Eastern Europe: Becoming White, Becoming Western,” in Relating Worlds of Racism. Dehumanisation, Belonging, and the Normativity of European Whiteness, eds. Philomena Essed, Karen Farquharson, Kathryn Pillay, Elisa Joy White, (Cham: Palgrave Macmillan, 2018), 113–139.) Representations of race in art in Eastern Europe under state socialism may therefore offer new insights into the trajectories of constructions of race in the supposedly homogeneous Eastern European societies.

For instance, by analyzing the racism behind the images of a supposedly anti–racist campaign, we have a chance to examine the evolution, impact, and consequences of race–constructions in the very midst of state–ordered anti–racism. The following analysis focuses on images of Angela Davis created by two small groups of the “New Left” in Hungary during the 1970s. I examine how these groups’ theoretical and ideological objectives diverge from their actual representation of Davis, thus overwriting the groups’ intended ideological goals and exposing not only the supposed color–blindness of these leftist intellectuals and artists, but also their covert racism.

During the period of socialism in the countries of the former Eastern Europe, class and race were interlocked issues: race was seen as a consequence of capitalism. Meanwhile anti–racism was used by official propaganda to highlight the moral and social hegemony of the socialist states in contrast with capitalist Western societies. Dorota Sosnowska argues that “to criticize the race one needs to criticize class at the same time, and the other way around, to criticize class one needs to criticizes race [sic].”(Dorota Sosnowska, “Halka/Haiti – White Archive, Black Body? Reenactment and Repetition in the Polish-Colonial Context,” re-sources.uw.edu.September 22, 2016, http://re-sources.uw.edu.pl/reader/halkahaiti-white-archive-black-body-reenactment-and-repetition-in-the-polish-colonial-context/.) If we think about racism in the social sphere, “the majority of Polish society was black for a very long time.”(Sosnowska, Halka/Haiti.) In this sense, Eastern European societies were racist in a color–blind way. For example, they routinely segregated underprivileged and vulnerable parts of society, including minorities, who were systemically disadvantaged. This hypocritical distortion of the ruling ideology of Marxism–Leninism with its promise of social equality cemented existing inequalities and triggered new ones, and it was the key disillusionment that resulted in the emergence of New Left ideologies among young intellectuals and artists in Eastern Europe after 1968 and during the 1970s. Searching for an “original,” “clean” form of Marxism, these critics appropriated non–Western political figures such as Che Guevara, Hồ Chí Minh, and Mao. Angela Davis also became one of these figures of identification—and the focus of a mural painting in a private apartment in Budapest conceptualized and initiated by a group of young Lukács-followers who identified themselves with the ideas of the New Left.

Angela Davis in Color

In 1970, Hungarian intellectuals claiming to be “Marxists,” “Trotskyites,” or “Maoists” gathered in a splendid apartment in the city center of Budapest. The apartment was the home of Ferenc Kőszeg, at that time editor of the publishing house “Szépirodalmi Kényvkiadó,” who later became a central figure in the democratic opposition and the founder and first director of the Helsinki Committee. (He still lives in the same flat.) These young intellectuals saw the writings of young Marx as a medicine that would heal the wounds of real-existing socialism.(See also for Maoism and Trotskyism in Hungary: György Dalos, “Éhségsztrájk anno 1971,” Mozgó Világ, March 26, 2000, https://epa.oszk.hu/01300/01326/00003/marciu2.htm. István Pap Szilárd, “‘1968 forró nyarán a magyar biliben mi voltunk a vihar’ – 50 éve zajlott a ‘maoista összeesküvők’ pere,” mérce.hu. July 14, 2018, https://merce.hu/2018/07/14/1968-forro-nyaran-a-magyar-biliben-mi-voltunk-a-vihar-50-eve-zajlott-a-maoista-osszeeskuvok-pere/.) However, the scope of these Maoist intellectuals’ actions was in fact very limited and they were hardly noticed in Hungarian society.(István Pap Szilárd, 1968 nyarán.) Nevertheless, theirs was the only youth movement worth mentioning in the country around 1968. Meanwhile, the government identified Maoism as an ideology hostile to the state, to the point that in 1968 a handful of young intellectuals were accused of “Maoist conspiracy” and tried.(György Dalos, one of the defendants in the 1968 Maoist trial, explains his interest in Maoism with the desire to show his solidarity with Vietnam, against the United States, more vigorously than did the official youth organization of the Hungarian Communist Party (KISZ). By contrast, solidarity with the Black Panther Party or the Black Power Movement was not at the forefront of solidarization in the Hungarian Left, see also: Dalos, Éhségsztrájk.)

Mao vehemently supported Black Liberation and the Black Power movement in the US and called for international solidarity against systemic racism, which he saw as directly linked with capitalism and “imperialism.” As he wrote in 1963, “I call on the workers, peasants, revolutionary intellectuals, enlightened elements of the bourgeoisie and other enlightened persons of all colors in the world, whether white, black, yellow or brown, to unite to oppose the racial discrimination practiced by U.S. imperialism and support the American Negroes [sic] in their struggle against racial discrimination.”(Mao Tse-Tung, Statement Supporting the American Negroes [sic] in Their Just Struggle Against Racial Discrimination by U.S. Imperialism (1963) marxist.org, https://www.marxists.org/subject/china/peking-review/1966/PR1966-33h.htm.) Black Maoism positioned Black Liberation movements “in relation to the larger colonial world—a world that included African Americans.”(Alexander Cook (ed): Mao`s Little Red Book. A Global History, (Cambridge, New York: Cambridge University Press, 2014); Robeson Taj P. Frazier, The East is Black. Cold War China in the Black Radical Imagination, Durham: Duke University Press, 2015); Robert Gildea, James Mark, Niek Pas, “European Radicals and the ‘Third World’. Imagined Solidarities and Radical Networks 1958-1973,” Cultural and Social History, 8, no. 4 (2011), p. 449–471. https://doi.org/10.2752/147800411X13105523597733.) This strategy was in line both with the Soviet embrace of Black Liberation and the Black Power movement. Mao Tse-tung’s appeal to solidarize with the black population in the United States was well-received by the US-American Black community. The “Little Red Book,” as the Quotations from the Chairman Ma Tse-Tung was called, was omnipresent in Harlem, and it also circulated in Budapest Maoist circles.

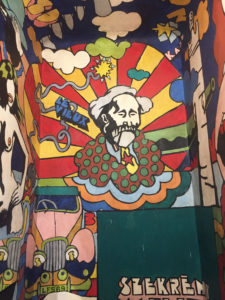

György Kemény. Secco, Detail view from the entrance, 1970–71, paint on dry plaster, flat of Ferenc Kőszeg in Budapest. Image courtesy of György Kemény/Ferenc Kőszeg. Photograph by the author.

Between Summer 1970 and April 1971, György Bence, a student of György Lukács’, and János Kenedi, an editor at the publishing house Magvető, rented a small room in Kőszeg’s apartment. They came up with the idea to create a mural on the walls—and Kőszeg agreed to paint the walls based on sketches by György Kemény, an artist and graphic designer. The mural’s iconography was an issue of heated debates during the design process. Kemény used the concepts decided on by the group, outlining the mural’s structure with black lines, and leaving it to the intellectuals to color it by hand. What did the mural look like? As you entered the room, the first thing you saw was a senile Marx with his eyes closed, with a pipe, in a polka-dot housecoat and with a five-pointed red star on his yellow scarf. Bombarded by LSD-missiles, Marx is hovering above a flower-power cloud and surrounded by a red and yellow rainbow. To his right, the barrel of a cannon is protruding. On the left, a bomb appears above a hammer and sickle, its fuse (above Marx’s head) on fire. The fuse says, “Le Vieux,” and in the right corner, we read the name “Karl.” To the bottom left, a colorful old-timer car juts into Marx’s field of vision, looking out from behind a naked figure cut off at the hips who is resting on all fours.

György Kemény. Secco, Detail with Karl Marx, 1970–71, paint on dry plaster, flat of Ferenc Kőszeg in Budapest. Image courtesy of György Kemény/Ferenc Kőszeg. Photograph by the author.

In stark contrast to Marx, on the front wall we see the US activist Angela Davis, with wide-open eyes and a bright gaze, depicted as an active, revolutionary philosopher in a characteristic “thinker`s pose” painted after a photograph dated November 27, 1969. Davis is positioned above a painted white screen (the result of a volcanic eruption) next to sexist comic-strip-like film scenes, and surrounded by a green, organic halo. Behind her, to her left, a red star or comet shoots out, while to her right there is a giant yellow flower. Above her head—with the characteristic Afro hairstyle—is written the German word “Rassenbewusstsein” (race consciousness), with a wide red arrow sticking out from it, while above the white screen we find the words “cine-eye” in Cyrillic letters, clearly a reference to Dziga Vertov’s kino-glas.

Presenting Angela Davis and Karl Marx as key protagonists of the mural combines class and race, an alliance of “black and red”(See also: Kate A. Baldwin, Beyond the Color Line and the Iron Curtain. Reading Encounters between Black and Red, 1922–1963, (Durham: Duke University Press, 2002); Joy G. Carew: Blacks, Reds, and Russians: Sojourners in Search of the Soviet Promise, (New Brunswick N.J.: Rutgers University Press, 2010) and for the East German context: Sophie Lorenz, “Schwarze Schwester Angela” – Die DDR und Angela Davis Kalter Krieg, Rassismus und Black Power 1965-1975. (Bielefeld: Transcript, 2020).)[x] that already appeared with Lenin.(Vladimir I. Lenin: Draft Theses on National and Colonial Questions. For the Second Congress of the Communist International, (June 5, 1920), marxist.org, https://www.marxists.org/archive/lenin/works/1920/jun/05.htm.) Race was a central element in Soviet propaganda, reaching its high point during the trial against Davis in the US.(The FBI put the twenty-six year old Angela Davis on the “Most-Wanted-Terrorists” list as a “possibly armed and dangerous” terrorist on August 19, 1970. She is the third woman ever to appear in this context. October 13, 1970, the FBI proudly presented Angela Davis in chains caught in a Manhattan hotel after a nationwide hunt.) The state-orchestrated solidarity action for Davis inside the Soviet Union and Eastern Europe targeted what it identified as pervasive racism in the US. On the pictorial level, however, we see an old, senile Marx—representing the past— being flanked by a young revolutionary, black female philosopher, Angela Davis, an icon of the future. The Budapest mural does not victimizes Davis, as the official Soviet propaganda did, circulating images like “Davis in chains” or the FBI’s “Ten-Most-Wanted” poster, but presenting her instead as a thinker, as a philosopher.

György Kemény. Secco, Detail with Angela Davis, 1970–71, paint on dry plaster, flat of Ferenc Kőszeg in Budapest. Image courtesy of György Kemény/Ferenc Kőszeg. Photograph by the author.

The term Rassenbewusstsein above Davis’ head was added by Ferenc Kőszeg. Davis herself never used the word in her work, but it clearly links her to the “godfather” of the New Left, György Lukács. A red arrow, starting at the inscription Rassenbewusstsein is connected with a red arrow starting at Klassenbewusstsein above Lukács’s portrait on the another wall, colliding on the ceiling in a huge explosion. Here the phrase “Klassenbewusstsein für sich” (“class-consciousness in itself”) hints at Lukács’s seminal book History and Class-consciousness. Lukács appears in the mural like Mephisto, an old man with wrinkles, above his student, György Bence. Behind Lukács, New York City, the capital of US-imperialism, is going up in flames. Like Marx, Lukács is part of a squad of old white men that leans on institutionalized forms of Marxism. Interestingly, Herbert Marcuse, the third “M” in the 1968-student protest movement (along with Mao and Marx) did not make it onto the mural. Instead, it is Marcuse’s most prominent student, Angela Davis, who hovers above Marx and Lukács, connecting the Frankfurt School with Lukács, representing a new generation of radical philosophers.

György Kemény. Secco, Detail with György Lukács and György Bence, 1970–71, paint on dry plaster, flat of Ferenc Kőszeg in Budapest. Image courtesy of György Kemény/Ferenc Kőszeg. Photograph by the author.

The wall where Davis would be added was the last to be painted when a heated debate broke out among the artists about who should fill the central position in the overall composition. Kőszeg recalls that there was no consensus: “One argument against her was the vigor with which the socialist Bloc supported the campaign for ‘Freedom for Angela Davis,’ while her mentor, Herbert Marcuse, was referred to as a ‘wolf in sheep’s fur.’ What spoke in her favor was that a year earlier, under pressure from the Governor of California, Ronald Reagan—as if this had happened in a socialist country—she had been relieved of her teaching position at the University of California.”(Ferenc Kőszeg, “Secco,” Magyar Narancs, November 5, 2009, https://magyarnarancs.hu/egotripp/secco-72555.) These opinions about Davis’ representation had precious little to do with her political philosophy or with her struggle against race and class injustice. Kőszeg comments: “Finally, feminism put aside, what also spoke for her that at that time, with her 26 years of age and a huge Afro hairstyle, she was exotic and sexy.”(Kőszeg, Secco.) In other words, including Davis in the mural was ultimately a decision that was motivated by her looks, highlighting the latent racism in many anti–racist efforts. The artists needed an exotic, powerful female icon that corresponded to the imaginary and iconography we associate with 1968. Despite this, Davis’ presence in the mural wields a theoretical, philosophical, and political power that disconnects it from the patriarchal, racist assumptions, becoming the representation of a heroine of black revolutionary Marxist philosophy in a genuine and universal sense.(See also: Kristóf Nagy, “Angela Davis Goes East? White Skin and Black Masks in the Art of Socialist Hungary,” World Literature Studies 8:4 (2016), http://www.wls.sav.sk/wp-content/uploads/07-Nagy-compressed.pdf.) As Kőszeg wrote with hindsight, “Perhaps without Angela Davis, Barack Obama would not have become president of the USA.”(Kőszeg, Secco.)

Interestingly, in contrast with the official solidarity campaigns in the GDR, the Hungary youth did not follow their government’s solidarity campaign for Davis with the same degree of enthusiasm. Although Davis was at the core of the “New–Left Chapel,” when Ferenc Kőszeg was asked by the author if he or his friends would have joined an official solidarity demonstration for Angela Davis, his answer was: never.(Interview by the author with Ferenc Kőszeg, October 20, 2020 in Budapest.) This might be surprising, given the open letter György Lukács had published in February 1971 in different European newspapers, and his further efforts calling for solidarity with Davis and demanding her immediate release from prison. The letter was signed by prominent writers and intellectuals such as Ernst Bloch, Martin Walser, Heinrich Böll, and Agnes Heller. However, in Davis’ case, the members of “Lukács’s nursery,” as his young followers were known, did not follow their master, even though Lukács’s protest letter was also published in Hungary.(Lukács, György, “Angela Davis ügyéért,” Nagyvilág, 16:6 (1971): 949-950.)

We can explain the resistance to open solidarity with Davis on the part of Bence, Kenedi, and Kőszeg with reference to the ambiguous nature of Davis’ image as both a black Marxist revolutionary (this is what catapulted her onto their mural) and as an official propaganda–icon that was used as such by the Communist governments.(See more on the ambiguity of Davis` image between state propaganda and subversion and the interrelation with the state security in Hungary, in: Kata Krasznahorkai, “Black Power in Eastern Europe: Angela Davis Between Socialist Heads of State and Artists,” in 1 Million Roses for Angela Davis, eds. Kathleen Reinhardt, Hilke Wagner, (Milano: Mousse Publishing, 2020), 83–87.) As Kőszeg told me an interview, they even considered removing Davis’ image shortly after its completion in April 1971, when her trial had come to an end and she was released from prison.(Interview by the author with Ferenc Kőszeg, October 20, 2020 in Budapest.) The release was celebrated by official state propaganda across the Eastern Bloc as a victory for the Soviet Union and its allies throughout the Communist world. Davis then started a tour across the Eastern Bloc, inviting high-ranking officials to celebrate her in mass rallies as their “sister.”(See also: Kata Krasznahorkai, “Black or White? Angela Davis, Bobby Seale und Black Power in den Akten der Staatssicherheit in den 1970er Jahren, in Aktionskunst jenseits des Eisernen Vorhangs, ed. Ádám Czirák, (Bielefeld: Transcript, 2019), pp. 157–182; Kata Krasznahorkai, “Von ‘Freiheit für Angela Davis’ bis Black Lives Matter. Interview mit Kata Krasznahorkai über Black Power in Osteuropa, Angela Davis und ihre Rezeption heute,” lisa.gerda-henkel-stiftung. October 6, 2020, https://lisa.gerda-henkel-stiftung.de/angela_davis.) At that point, her image on the walls of the Budapest apartment seemed to finally contradict its creator’s anti–state policy. However, Kőszeg added that now, fifty years later, Davis’ presence in the mural is in fact more appropriate there than ever: the struggle she was fighting has not come to an end, and her demand for race consciousness without black nationalism is still a valid and compelling one.

Angela Davis in Black and White

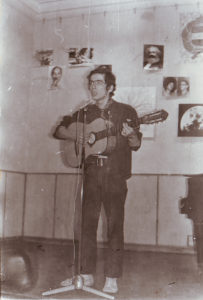

Davis’s representation as a pop art icon stands in stark contrast to the depictions of her made by another group of artists who were also sympathizers of the New Left and Mao. Its founder, István Malgot, was sentenced in the abovementioned Maoist trial. The artists belonging to this collective, later known as the Orfeo Group, evolved out of a group of art students at the Budapest Academy of Fine Arts and founded the puppet theater group Orfeo Studio in 1969. Later, a music group called Orfeo Band, as well a studio of photography and graphic art, were added. It was a leftist group of artists who wanted to reform existing socialism by merging Maoist ideals, praising Hồ Chí Minh, Che Guevara, and Marx’s ideas with their art.(Márton Szarvas, “Orfeo’s Maoist Utopia. The Emergence of the Cultural Critique of Existing Socialism,” MA thesis, 2016, ceu,http://www.etd.ceu.hu/2016/szarvas_marton.pdf.)

Members of the Orfeo Group at the Angela Davis Club, 1971, black and white photograph, Budapest, Kinizsi utca 1/b. Image courtesy of Anna Komjáthy. Photographer unknown.

Initially, Orfeo was tolerated by Party officials, and the state even supported them by allowing them to use the locations of the Hungarian Young Communist League (KISZ) and the Patriotic Popular Front (HNF).(The Patriotic Popular Front was a special social organization between 1954 and 1990, whose goal was “to unite all classes and strata of Hungarian society.” It had no individual membership, it functioned as a mass movement. It united all the elements of the political system of the time, the ruling Communist Party MSZMP, mass organizations, and social and cultural organizations.) They appeared in official media and held public appearances until 1972.(In 1972, the Orfeo group was labeled officially as “radical,” which meant it had crossed the line of the state’s tolerance. After a scandalous newspaper review, Orfeo was banned and prohibited from any public appearances, see also: Szarvas, Orfeo`s Maoist Utopia.) Initially, Orfeo had permission to hold their events at the Youth Club in Budapest’s IX district, naming it the “Angela Davis Club.” As Tamás Fodor, one of the group members, recalls, the name was chosen more out of necessity than conviction, and for a familiar reason: “What we would have chosen according to our hearts, we were not allowed to, because Che Guevara’s name was taboo. Therefore we named the club after Angela Davis. But the choice of name was tricky because the civil rights activist had declared herself a militant communist, so she was officially presentable; but at the same time, she sympathized with the Black Panther movement, so she was also accepted by enthusiasts of the New Left.”(Orsolya Ring, “A színjátszás harmadik útja és a hatalom. Az alternatív Orfeo Együttes kálváriája az 1970-es években,” Múltunk. Politikatörténeti Folyóirat 53:3 (2008): 224–240, 244.) Another Orfeo member, István Malgot, adds that exoticization played a role, too: “The Third World had its own myth and metaphorical content anyway. It had something romantic, naive, and revolutionary about it.”(Ring, A színjátszás harmadik útja, 244.) Such romanticization of course is in itself racist, and all the more so since Davis was not in fact a “Third World” heroine at all, but an African-American US citizen who had actually resisted being mobilized for the Pan-African Movement, or for any nationalistic Black Liberation agenda for that matter.(Zsuzsa László, “Limits of Solidarity. Hungarian Intelligentsia and the Middle East in the Cold War,” mezosfera.org, May, 2018, http://mezosfera.org/limits-of-solidarity/.)

Orfeo Studio. Orfeo`s Love, with “Panyiga” (János Vas) in the background with two images of Angela Davis, 1969, Kőbányai Ifjúsági Klub, Budapest. Image courtesy of Anna Komjáthy. Photographer unknown.

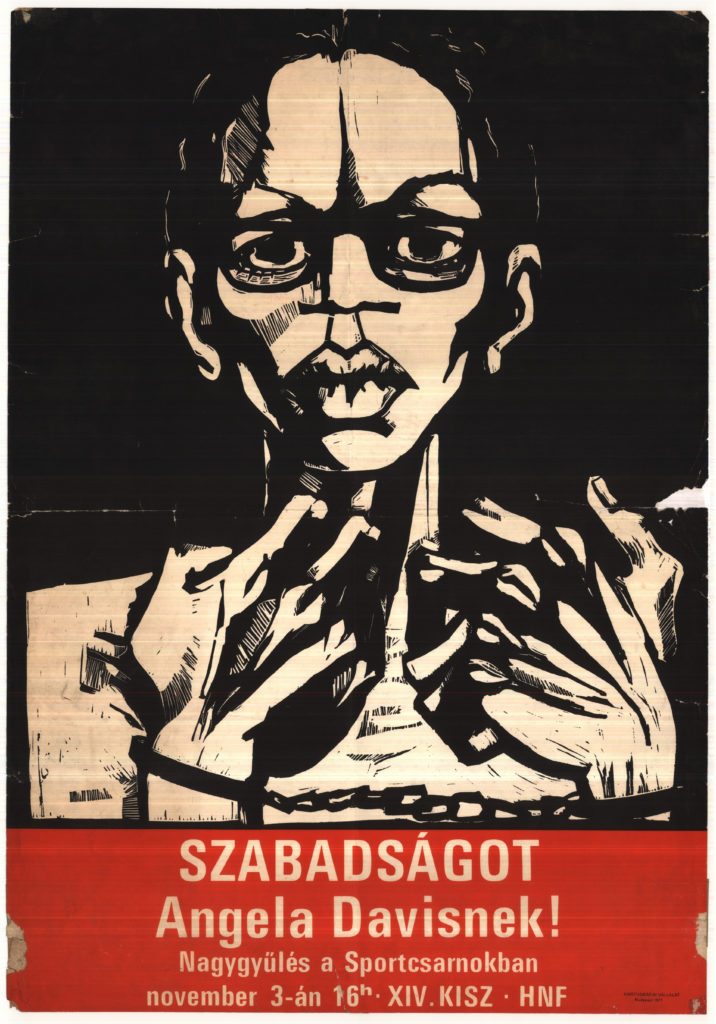

Davis’ image also appeared as part of the set design for one of Orfeo’s puppetry productions, Orfeo’s Love, a play about Che Guevara. But also as a poster on one of the walls in the Angela Davis Club. When the Patriotic Popular Front received a request to organize a large-scale solidarity event in Budapest with Fania Davis, Angela Davis’ sister, in March 1971, they commissioned Orfeo to organize a solidarity rally in the Budapest Sports Arena. The artist Anna Komjáthy, at that time Malgot’s wife, was responsible for Davis’s visual presence on posters, flyers, wristbands, and invitations during the event. The image Komjáthy chose for a lithograph and also in an ink drawing was based on the famous press photo that showed Davis in handcuffs after her arrest in New York, her hands in the air with a stern, admonishing expression on her face. Davis’ hair is strictly combed backwards as she demonstratively holds her chains in front of her. Komjáthy’s lithograph became the official poster displayed on Budapest’s streets in 1971, inviting the population to the mass rally with Fania Davis as a sign of solidarity with Angela Davis.

Anna Komjáthy. Poster for the Solidarity Event for Angela Davis, November 3, 1971, litography, Budapest Sportcsarnok. Image courtesy of Anna Komjáthy.

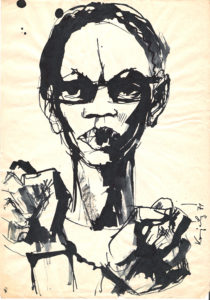

There is no trace, in Komjáthy’s image of Davis, of the 1960s pop aesthetic, no Afro hairstyle, and none of the sexualized or eroticizing representation we witnessed in the aforementioned mural. Instead in the black and white lithograph in the style of a wood-cut, there is no place for romanticization or exoticization. Komjáthy does not present Davis as a pop star, a thinker, or a philosopher, but as a political activist, and as the victim of racialized capitalist repression deriving from slavery. More than anything, Komjáthy’s image of David recalls a series of outstanding wood-cuts depicting a 1514 Hungarian peasants’ uprising by the widely-known socialist artist, Gyula Derkovits, that was commissioned by György Lukács in 1928. In her own work, Komjáthy depicts Davis in the style of one Derkovits’ peasant revolutionaries, emphasizing the social misery that accompanies the fight against the ruling class. For Komjáthy, Davis is primarily a victim of racism and capitalism who fights for a socially oppressed minority. Komjáthy universalizes this fight and extends its radius from the suppression of Black people to the repression of the “proletariat” and socially vulnerable minorities. In this way she gives Davis’s anti–racist agenda and political fight a strong social dimension that reflects on the ongoing struggle of the economically disadvantaged parts of society.

Clearly, Komjáthy does not foreground Davis’ race, and when I asked her whether she or the Orfeo Group members had thought about applying Davis’ anti–racist struggle to the systemic problems and inequalities in their own, Hungarian, society, Komjáthy was surprised.(Interview by the author with Anna Komjáthy, September 28, 2020 in Budapest.) As she recalled, no such use of the image was ever discussed in the group. In fact, she went on, the issue of racism in their own society was not a topic they even considered important, despite the fact that solidarity with Davis was at the core of their activities at that time. The only engagement with racial issues she remembered had to do with Orfeo’s activities in the area of social photography, which involved taking pictures of Roma villages and their inhabitants. But otherwise the question of race or ethnicity, especially along color-codes, was for them an issue that belonged to the relatively distant United States.

Anna Komjáthy. Angela Davis, 1971, ink drawing, Budapest. Image courtesy of Anna Komjáthy.

However, I want to suggest that also in this case, Davis’ image has overwritten its creators’ agenda. As we saw, and despite Malgot’s claims to the contrary, Komjáthy’s lithograph did not incarnate Davis as a romantic revolutionary with an exotic aura, or as a pop-star. Instead her image becomes what I would call an autonomous “acting image.” This is an image that unfolds its radius in its own way, unintended by its creators and their calls to action. Angela Davis’ images radiate in this sense until today, and calls for a struggle against systemic racism and for the universality of Human Rights and equality before the Law.

This analysis of the “acting images” of Angela Davis appropriated by the New Left in Hungary has shown the divergence inherent in ideological and visual representation, and how it can lay bare different forms of racism. On the one hand, we have “Angela Davis in color”: color–coded, with her racialized image exoticized, revealing inherent racism (and sexism). On the other, we have “Davis in black and white”: negating color, being color–blind on the racisms that target socially vulnerable parts of (Hungarian) society. But these two images of Davis also act autonomously in both examples, overwriting their creators’ ideological intentions and unveiling inherent structural racisms. The consequences of these structural racisms are still felt (not only) in Hungary today, where images of “otherness” are instrumentalized by right-wing, xenophobic, racist anti–migration state–propaganda once again. But this time, not in the name of solidarity, but fostering racism in the name of the “saviours” of so-called “European, Christian values”—giving Angela Davis` slogan renewed relevance also in Eastern Europe: “In a racist society, it is not enough to be non-racist. We must be anti-racist.”

Research for this article at the University of Zurich is funded by the Gerda Henkel Foundation.

This article is part of the Special Issue Art and Race in Contemporary Central and Eastern Europe. You can find links to the other articles in the special issue below: