The Paintbrush Factory: A Changing Ecosystem of Labor, Fragility, and Community

The Paintbrush Factory, Cluj-Napoca. Image courtesy of The Paintbrush Factory. Photograph by Șerban Bonciocat.

As I write this piece, numerous narratives are being produced and reproduced in relation to the history of Fabrica de Pensule / The Paintbrush Factory, a collective space devoted to contemporary art and performing arts founded in 2009 in Cluj-Napoca, Romania. Known for being the most ambitious independent art space in Romania, the Paintbrush Factory functioned between 2009 and 2019 in a rented industrial building that inspired its name – a former paintbrush factory. In the autumn of 2019, the private owners of the space decided to raise the rent and search for business tenants, following the trends of gentrification happening in the area. This moment was marked by members of the Paintbrush Factory through a series of exhibitions, performances, and debates about what it means to work independently and how can art engage with issues of the present. The series, under the title The Paintbrush Factory – Ten Years, ended one chapter and pointed to the beginning of a new one.

Artist Răzvan Anton in his studio at The Paintbrush Factory. Image courtesy of The Paintbrush Factory. Photograph by Roland Vaczi.

For ten years the Paintbrush Factory was a generator of creative energy for the local art scene and a “community-built institution” that received international acknowledgement quite quickly after its launch. It was structured as a federation of different cultural organizations and art galleries (AltArt Foundation, Plan B Gallery, Sabot Gallery, Lateral Art Space, ColectivA, GroundFloor Group, and many others), as well as independent artists (among them, Răzavna Anton, Marius Bercea, Radu Cioca, Oana Fărcaș, Cristina Gagiu, Mihai Iepure Gorski, Adrian Ghenie, Ciprian Mureșan, Cristian Rusu, Șerban Savu). After the closing of the physical space and a series of internal ruptures, a few of the initial members together with new collaborators reinvented the Paintbrush Factory, transforming it into a nomadic project oriented towards networks and research. (The current team of the Paintbrush Factory is Simina Corlat, Helga Thies, Theia Golea, Alexandra Chițu, Cristian Iacob, Răzvan Anton, Mihai Iepure-Górski, Kinga Kelemen, Istvan Szakáts, and Rarița Zbranca. ) Both the building’s closing and division of its members occasioned many discussions and debates on the role, mission, accomplishments, and failures of the Paintbrush Factory during its history. With this in mind and my involvement as an active member (2012-2018), I will not attempt to rewrite its history or retrace its glorious moments in a nostalgic effort to bring back the Paintbrush Factory’s importance. Rather, I wish to reflect on some of its strengths and weaknesses regarding labor, fragility and community that I believe might go deeper into the various discourses built around it. Thus, this text is not an obituary for the Paintbrush Factory, but rather a personal account focused on its first ten years (2009-2019) – what triggered the creation of this project, the stages it went through, and the ideas one can distill from a project that defined the contemporary art scene in Cluj for a decade.

The Paintbrush Factory was the first project in Romania to convert an industrial building into a contemporary art center, and to bring together a large community of artists and cultural workers – at one point around eighty members. As such, it started as a collective of art spaces, commercial galleries, artist-run spaces, studios, and performing arts organizations (From 2009 to 2019 members included: visual arts NGOs (AltArt Foundation, Cluj Est, Plan B Foundation, Intact), for-profit galleries (Plan B Gallery, Sabot Gallery); artist-run spaces (Bazis, Baril, Lateral Art Space, Superliquidato, Peles Empire, Pilot, Raft), performing arts organizations (ColectivA, GroundFloor Group, Arta Capoeira, Grupa Mică Association, Art-hoc, Balla & Vajna Projects); artists’ studios (Smaranda Almășan, Răzvan Anton, Dragoș Bădiță, Maria Balea, Dan Beudean, Marius Bercea, Maria Brudașcă, Andreea Ciobîcă, Radu Cioca, Istvan Cîmpan, George Crîngașu, Radu Comșa, Cristina Curcan, Denisa Curte, Oana Fărcaș, Robert Fekete, Cristina Gagiu, Adrian Ghenie, Attila Gräff, Simon Cantemir Hauși, Mihaela Hudrea, Ioana Iacob, Mihai Iepure-Gòrski, Lucian Indrei, Hortensia Mi Kafchin, Gabriel Marian, Irina Măgurean, Ciprian Mureșan, Flaviu Rogojan, Eugen Roșca, Cristian Rusu, Șerban Savu, Mircea Suciu); cultural managers (Corina Bucea, Miki Braniște, Cristina Bodnărescu, Simina Corlaț, Florin Caracala, Alexandra Chițu, Kinga Kelemen, Mădălina Stănescu, Istvan Szakáts, Rarița Zbranca, and many others) – all active within an old paintbrush factory in an off-center area in Cluj-Napoca, a university city located in the northwestern part of the country. (The original Paintbrush Factory on 59-61 Henri Barbusse street, in the Mărăști neighborhood, functioned until 2005 in two stages: first as a state factory between the 1970s and 1991, and then as a private company.) Since there was no previous model in Romania to follow, it had to learn as it went along, constantly defining and redefining what constitutes the “common good,” while finding the resources, both financial and human, to keep going.

From 2009, when it first opened its doors, until 2019, when the industrial space closed, a large number of shows, festivals, exhibitions, and workshops took place in a very dynamic rhythm, with more than fifty events per year, involving more than 100 artists, cultural workers, managers, and curators during each season. The lively, creative spirit of the Paintbrush Factory has been recognized not only on a national level (more than 1,000 people participated in its inaugural events), but also internationally, with a number of articles and exhibitions that put Cluj-Napoca on the global map. (See various articles in the international press: Zeke Turner, “Art Matters | A Medieval Romanian City with Major Art Talent,” New York Times, T Magazine, November 12, 2013, https://tmagazine.blogs.nytimes.com/2013/11/12/art-matters-a-medieval-romanian-city-with-major-art-talent/; Marie Maertens, “L’ecole de Cluj,” Art Press, no. 365 (2010): pp. 58-64; Jane Neal, “The Two Art Centers of Romania: Cluj and Bucharest,” Res magazine, no. 5 (2010): pp. 52-69; “Here Are The 12 Cities That Will Shake Up the Art World in The 21st Century,” HuffPost, September 1., 2013, https://www.huffpost.com/entry/art-cities-of-the-future_n_3949998.) By the time the international press had “discovered” Cluj-Napoca, some artists – those hastily branded as the Cluj School of Painting in the commercial manner of the marketing machine – already made a name for themselves on the global art scene, many on behalf of the tireless efforts of Plan B Gallery in Cluj and Berlin to promote a new generation of artists. Alongside such well-known artists as Adrian Ghenie, Șerban Savu, Victor Man, Marius Bercea, and Mircea Suciu, new generations of neo-conceptual artists emerged from this exceptional moment, including Ciprian Mureșan, Mihai Iepure Gòrski or later on Flaviu Rogojan.

Narrating images / Imagining stories, group exhibition with: Adorjáni Márta, Flaviu Cacoveanu, Norbert Costin, Oana Hodade, Lucian Indrei, Nita Mocanu, Adela Muntean, Esra Oezen. Galeria Plan B Cluj. Image courtesy of The Paintbrush Factory. Photograph by Roland Vaczi.

Building a New Ecosystem

When the Paintbrush Factory was formed, it brought together established artists and newcomers, known galleries and emerging ones, experienced managers and their younger peers. This mix came with a certain risk and unpredictability, but also shaped a strong sense of community. The fundamental need that the Paintbrush Factory was built upon came from members’ desire to have proper exhibition spaces and studios as well as share expenses at an affordable price (in a city where rents have become some of the most expensive in Romania). Later on, the idea of building community became more consciously integrated into its mission statement, which took an interdisciplinary approach by bringing together the visual and performing arts. The former paintbrush factory seemed the right place for this, and its history became the subject of future projects, recast in creative ways and integrated into a larger cultural discourse about the reconversion of industrial patrimony, while giving back to the city a piece of its history. The Paintbrush Factory was also a lesson in how bottom-up initiatives can radically change the anachronic status-quo of the city of Cluj. At that time, the city was struggling with a “tired” artists’ union, an uninteresting art museum, and a conventional art university. However, there were also initiatives and models that activated the experimental and critical side of the art scene long before the birth of the Paintbrush Factory, including Casa Tranzit, Studio Protokoll, Balkon journal turned into IDEA arts + society, Galeria Ataș.

The original structure of the Paintbrush Factory was simple and important to note: everybody was welcomed to become a member as long as spaces were available for rent and as long the board of directors confirmed them. Each member had a vote in the General Assembly regarding the main decisions of the federation, while a board of directors was elected annually on a representative base. All of the various disciplines and factions of the federation – artists, art galleries, performing arts NGOs – were part of the decision-making process in weekly meetings dedicated to administrative issues, programming, and community related events. The Paintbrush Factory’s elected president had a diplomatic role, acting as a mediator and registrar of official documents. The decision-making process was nonhierarchical, and this collectively run institution supported itself and its members through grant applications and other fundraising strategies. (One of the most successful strategies of fundraising was the auction at Tajan in Paris with works donated by artists-members of the Paintbrush Factory sold with the purpose of creating a common fund.) The building itself was initially rented from a private company for a reasonable price then later for a much higher price, until the predictable gentrification process occurred, and the building was transformed by the owner at the end of 2019 into an IT business site.

The programming of the Paintbrush Factory tried to synchronize at least twice a year, and the gallery openings, theater shows, open studios, and other events were promoted as three-day marathons at the beginning of the season in October, and then in June to run concurrently with the Transylvania Film Festival opening. Some of the most visible and important projects included, for example, the organization of Cluj Art Weekend in 2014, a full program of events that extended into the city and involved a large number of exhibitions, such as the exhibition Future Fabulators organized by AltArt Foundation and including the group Times’Up (AT) and other artists in a dystopic setting that explored fictional stories, day-dreaming and oneiric worlds. Other noteworthy exhibitions include: Between the Lines at Plan B Foundation, with works by artists Ion Bitzan, Andreea Ciobîcă, Mihai Olos, Miklós Onucsán, Sorin Vreme, and others, who use drawing as a conceptual tool, and the solo shows of Nicolás Lamas, subREAL group, Arantxa Etcheverria, Szilárd Gáspár, at galleries Sabot, Baril, Bazis, and Intact, respectively. The artist-run spaces Lateral and Superliquidato highlighted the young art scene through experimental and edgy exhibitions. It is also worth mentioning the many significant editions of the TEMPS D’IMAGES Festival, and various performance shows, such as the awarded-winning Parallel, produced by GroundFloor Group.

X Centimeters Out of Y Kilometers, directed by Gianina Cărbunariu. Temps d’Images, 2011. Image courtesy of ColectivA. Photograph by Voicu Bojan.

Good marketing, press reviews, alongside exhibitions abroad dedicated to the Cluj art scene – usually placed in continuity with a tendency, going back to the 1990s, of bringing the so-called “periphery” closer to the “center” of the international art scene (A selection of the exhibitions focused on the Romanian art, and Cluj-Napoca in particular, includes: Cluj Connection, Haunch of Venison Gallery, Zurich, CH (2006); Hotspot Cluj – New Romanian Art, ARKEN Museum of Modern Art, DK (2013);Scènes Roumaines, Espace Culturel Louis Vuitton, Paris, FR (2013); A Few Grams of Red, Yellow, Blue. New Romanian Art, Centre for Contemporary Art Ujazdowski Castle, Warsaw, PL (2014).) – created a myth around Paintbrush Factory, although it was born spontaneously from a collective set of needs rather than from an actual rigorous institutional planning. This myth had also created some backlash, as artist Ciprian Mureșan cynically observed in 2010: “You can only resign to the thought that, probably, in the Romanian context a ‘successful’ unusual history, though absolutely contingent, [the Paintbrush Factory] could not have been assimilated but in terms of some clichés.” (Ciprian Mureșan, “The Paintbrush Factory: Snapshot. Diapositives from One Year of Existence,” IDEA arts + society, no. 36–37 (2010), p. 51.) The outcome of this “aura” that started to appear around the cultural production coming from Cluj-Napoca was twofold. On one hand, it generated pressure and a competitive atmosphere inside the members of the Paintbrush Factory because, of course, there is no democratic way of being represented in a subjective account in the press nor equal visibility anyone could control. On the other hand, the success brought forward by these “confirmations” triggered bigger financial ambitions and grants to be managed, divided, prioritized, and customized according to the diverse profiles of its members.

Besides these dual issues spawned by international success, there is also a subject worth mentioning, one that has rarely been addressed in the various analyses dedicated to the Paintbrush Factory: the conflicting politics and visions that ultimately led to division in 2016 when some members left and created another art “factory” called Center of Interest. The political affinities of each member, their aspirations and visions concerning the mission of the arts and cultural community contributed to the division that took place in 2016, when part of the Paintbrush Factory members left after unleashing a quite unworthy series of press denigrations targeting their former colleagues. In my opinion, the initial conflicts had their source in the vision each member projected onto the Paintbrush Factory – community versus individualism. Some members considered this project an alternative, independent institutional structure capable of representing a cultural community created by its members that advocates for artists and their sociopolitical role. For them, the Paintbrush Factory functioned as a nonhierarchical and flexible platform for all its members, one based in collectively and on interdisciplinary models that created intersections between the performing and visual arts. Other members considered this unique aggregation of diverse members as an opportunistic strategy of being together while being apart, while taking advantage of the prestige gained over time by the overarching structure and having access to the financial resources that the Paintbrush Factory distributed amongst its members. “In reality, we are a constant work in progress, negotiating with the external and internal pressures of an organization that fills in the gaps left out by institutions,” stated Corina Bucea, the Paintbrush Factory’s first and most longeval manager, in 2018. “It is something we took responsibility for, but partly it has also been transferred upon us from a community and from an audience which would otherwise have the same expectations towards institutions. The answer to this pressure is a constant negotiation inside our community of members which vary greatly in terms of background, experience, political views – a diversity directly proportional to the number of internal conflicts or at least dilemmas we have been facing constantly since the inception of the Paintbrush Factory.” (Corina Bucea, presentation in tandem with Diana Marincu, at the conference “Art and political space in Europe,” 2018, organized by Kunstenpunt / Flanders Arts Institute in Brussels.)

The fact that no selection criteria was applied for newcomers and that the key trait of the collective identity was so much related to the autonomous position of each member had its consequences. While some colleagues were preparing their next exhibition of internationally acclaimed artists, others were doing community interventions in the Mănăștur neighborhood and Pata-Rât area. While some members were expanding or renovating their spaces, others were being threatened with eviction because of their delay in paying the rent. While some galleries were producing popular and visible exhibitions, others turned towards educational projects. While some artists identified with the community, others considered themselves simply tenants. This lack of a solid base of common goals, I think, in the end, had its impact.

István Szakáts, cultural worker and founder together with Rarița Zbranca of AltArt Foundation, noticed quite as early as 2010, that “the plurality of voices existing in the Paintbrush Factory turns the effort of finding an ideological common denominator superfluous and even a bit intruding. There is no Big Ideology that the members will adhere to. As an example, key words such as Responsibility and Development can be and are understood at times radically different by the members of the Paintbrush Factory, and in that case, the factory looks more like a shoal whose trajectory you can predict collectively, but not individually, in each fish’s case. Thus, the whole process of repurposing the existing patrimony should be seen on a practical level, based on practice, having the value of praxis.” (István Szakáts, “Între sus și jos [Between up and down],” in Fabrica de Pensule, eds. Corina Bucea and Székely Sebéstyen György (Cluj-Napoca: Fundația AltArt and Fabrica de Pensule, 2010), pp.12-13. English translation by the author of this text.)

Labor

Privileging praxis over any kind of common institutional and political discourse is understandable from the point of view of the plurality and horizontality proposed by the federation. However, the different types of praxis created another clash between the various kinds of labor and the types of “intelligences” that contributed to the activities of the Paintbrush Factory. In truth, the different expertise that the members brought forth were never acknowledged as equal with the artistic creativity that the artists were building their careers on. A myth of the magnetic power of the artist outran many other qualifications that were equally important and vital for the Paintbrush Factory. Cultural managers were hardly rewarded properly for their efforts, educators were always seen as marginal in the whole structure, and technicians were never considered as members with equal rights. This reality was both projected from the outside and perpetuated from the inside, triggering a paradoxical situation: the Paintbrush Factory neither showed a constant solidarity with the precariat, nor did it display a self-conscious alliance with the art market.

Theorist Andrea Phillips tackles the issue of these diverse instances of intelligences and multiple authorships in her recent text, “Critical production and the intelligence of collective technicity,” where she looks at “an alternative mode of understanding cultural production that is based on the equality of value of intelligences.” (Andrea Phillips, “Critical production and the intelligence of collective technicity,” in Art Encounters Biennial 2019, eds. Maria Lind and Anca Rujoiu (Timișoara: Editura Fundația Art Encounters, 2019), p. 299.) The different, but equal intelligences that Phillips is committed to bringing forward while talking about the decentralization of art labor, rarely correspond to the production of equality: “So often in contemporary art, collaboration is fantasized, fetishized and misconstrued. Collaboration in art production takes place on a constant basis but is not named as such. How does the work of managing and organizing produce unaccounted value, and how could a committed investigation of production―of organization―help to proliferate and expand the ways in which we might recognize each other, communicate, fund and work together?” (A. Phillips, “Critical production…”, p. 302.)

If we were to understand the importance of equality of the knowledges earlier, perhaps the internal unbalances of the Paintbrush Factory could have been addressed, corrected, and repurposed in a more progressive way, even contributing fundamentally to the definition of the cultural worker today. Visibility and prestige do not always faithfully reflect all the facets of a space of production such as the Paintbrush Factory. Still, some of the members felt deprived of reputation or fame, in the eyes of the critical apparatus, that only reflects a superficial surface out of the many to be analyzed. The late Marion von Osten, one of the most vocal promoters of collaborative practices in the sphere of cultural production, states: “A start would be to conceive new trans-institutional structures in our work lives. That would be to take the situation with which we began—knowledge is being produced everywhere and by many actors, not just academics or artists—a lot more seriously. To my mind, this also means that we call the existing binary and hierarchical opposition between intra-institutional and extra-institutional knowledge-production into question, in the existing public institutions and in our self-organized production.” (Fahim Amir, Eva Egermann, Marion von Osten, and Peter Spillman, “What Shall We Do…?,” e-flux Journal no. 17, June-August 2010, https://www.e-flux.com/journal/17/67397/what-shall-we-do/.)

Fragility

The identity of the Paintbrush Factory integrated in a natural way the fragility of the context it was embedded in – a context marked by the lack of a public policies protecting the arts and cultural sector (in terms of wages and fiscal laws), and of a consistent financial support dedicated to the development of the cultural scene in the long term. But besides the Paintbrush Factory’s heroic existence within this external fragility, I believe there is much more to be discussed in relation to internal fragility. The concept of fragility, in the words of researchers and writers Jesús Carrillo and Francisco Godoy Vega, “allows for creating a diagnosis about the unstable balance in which contemporary society is built and its process of subjectivisation, functioning, from a materialistic point of view, beyond the threat of strictly symbolic instability.” (Jesús Carrillo, Francisco Godoy Vega, “Fragility,” in Glossary of Common Knowledge, 2015, http://glossary.mg-lj.si/referential-fields/subjectivisation/fragility#_ftn1.)

This idea of fragility is integrated in the “Glossary of Common Knowledge” (http://glossary.mg-lj.si/about-gck.), an alternative compilation of art terminology created in the frame of L’Internationale confederation. It stands as a possibility of alliances between different “ecologies,” such as those invoked by Carrillo and Vega and in continuation with Félix Guattari’s proposal for three ecologies: the environment, social relations and subjectivity. Fragility is seen here as a revolutionary vehicle, a “war machine,” and as a way of dismantling the existing mainstream structures of the state and the market, by intertwining the three ecologies mentioned and acting simultaneously on all three levels. The process of fragilization has the potential to build the “common” from scratch and to create alliances capable of “weaving new ecologies for creation and cohabitation.” (Jesús Carrillo, Francisco Godoy Vega, “Fragility,” http://glossary.mg-lj.si/referential-fields/subjectivisation/fragility#_ftn1.). In my view, the theorization and implementation of the fine balance and assumed fragility that a new discursive format of the Paintbrush Factory could build upon would create a meaningful agency for this institutional structure.

At this moment, the Paintbrush Factory is no longer a space, but a set of ideas and projects derived from the process of dematerialization that occurred. The partnerships and networks that the new version of the Paintbrush Factory started to build are actually the main focus of artistic activity – cooperation, research, production, and dissemination programs about contemporary art in the fields of visual arts, performing arts, cultural formation, and audience development.

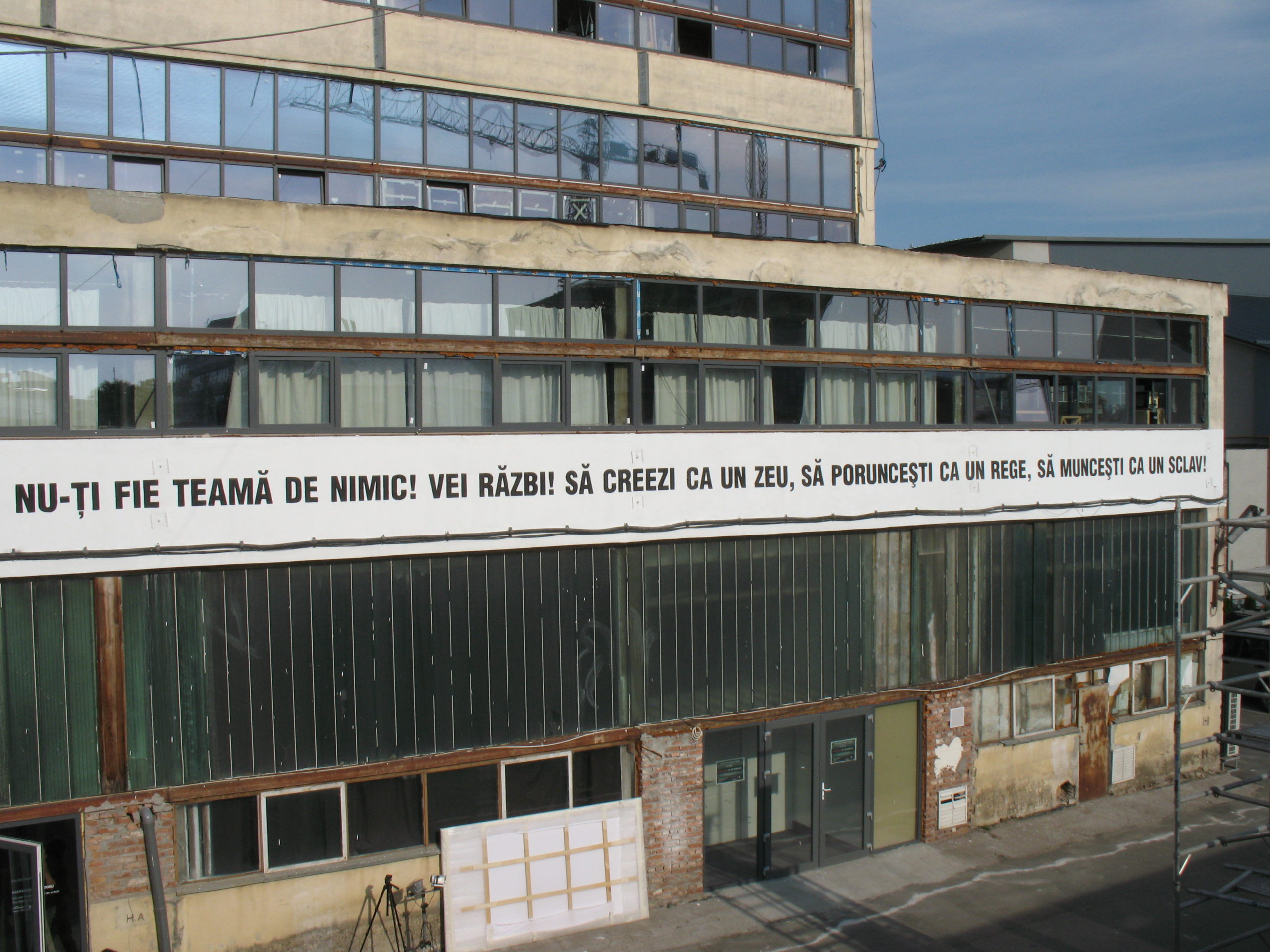

Alexandra Croitoru. Do not forget you are an artist! Do not be discouraged, do not be afraid, you will make it! Create like a God, order like a king, work like a slave!, 2012. Intervention on the the façade of The Paintbrush Factory. Image courtesy of Galeria Plan B Cluj / Berlin.

Community

Building common ground is the most difficult task to take. According to theorist Pablo Martinez, community is related to an attempt to repair the fragmentation of today’s individualized society: “Community does not mean an immediate identification between lookalikes, but a continuous work of negotiation and collective struggle; a wager for time that is shared.” (Pablo Martinez, “Community,” in Cluster: Dialectionary, eds. Binna Choi, Maria Lind, Emily Pethick, Nataša Petrešin-Bachelez (Berlin: Sternberg Press, 2014), p. 77.) The task of building a community became part of the mission of many art institutions in the nineties, which were expected to develop working methodologies that would respond to the crisis of the museum and art institutions in general. Art historian Alina Șerban frames the activity of the Paintbrush Factory within the New Institutionalism model of organization defined as the “interaction with its own social context, based on an alternative value system.” (Alina Șerban, “Individual, group, community,” in The Paintbrush Factory, eds. Corina Bucea and Diana Marincu, 2016.) Nevertheless, the transition from an institution to a community center, according to Charles Esche focuses entirely on the shift of the arts towards a social framework, a process that happened partially in the case of the Paintbrush Factory, but which can become a future goal for its future incarnation. The main ambition of working with communities and engaging different audiences ideally turns the audience into collaborators and the public into “active shapers of the institutional message.” (We were learning by doing’ An Interview with Charles Esche,” ONCURATING.org (New) Institution(alism), Issue 21 (December 2013), p. 26.)

Many things have changed since the first gains made by New Institutionalism, or Experimental Institutionalism, as Esche refers to this tendency to engage new audiences and connect deeper to the social and political fabric of a certain context. I believe there are still several steps to take in order to rethink art’s potential in the struggle between localism and internationalism. The new mission that the Paintbrush Factory adopted after the closing of its industrial space in 2019 and the shrinking of the team engages a different paradigm that might prove stronger in the long term, particularly if it focuses on networks, collaborations, and professional formation. However, it is also perpetuating an amnesic look at its own past and collective memory. What the Paintbrush Factory missed, as many other institutions in Romania did, is the “self-historicization” process, a self-analysis of the many layers of its current identity and an acknowledgment of all the individual contributions that created this complex institution that for ten years was regarded as a model for the Romanian art scene.

When curator Zdenka Badovinac talks about self-historicization in relation to East European art during the socialist times, she defines it as “an informal system practiced by artists who, in the absence of any suitable collective history, were compelled to search for their own historical and interpretative contexts.” (Zdenka Badovinac, Curating, Art, and Politics in a Post-Socialist Europe (New York: Independent Curators International, 2019), p. 319.) Although today we have the tools and expertise to invest in the histories of the institutions created by artists and independent art professionals in Romania in the last thirty years, we rarely reflect on how “alternative” institutions shape the art scene and how they influence the critical perspective needed to enact, react, and transform “official” structures.

As a parallel, one might look to the autonomous art institutions in Hungary between 1989 and 2009, as reflected in the book We are not ducks on a pond but ships at sea,” a context which, similarly to the Paintbrush Factory case, “begins and ends with a void.” In Katarina Šević’s words: “Most often referred to as ‘artist-run,’ ‘independent,’ ‘alternative,’ ‘grass-roots,’ ‘collective.’ ‘bottom-up,’ and the like, these temporary spaces and initiatives in fact elude definition. Such projects are set in non-bureaucratic structures, appearing, disappearing, and transforming? themselves by using a wide range of tactics. To top it all, they only rarely leave traces of documentation.” (Katarina Šević, “Introduction: Between the Theater and the Museum,” in We are not ducks on a pond but ships at sea, eds. Kálmán Rita, Katarina Šević (Budapest: Impex, 2010), p. 5.)

The “traces” of the Painbrush Factory may be fragmented, hidden, suppressed, or diverse in their interpretation. However, I think that an assumed view from the inside out could strongly counter all the various narratives projected from a distance and privilege first-hand knowledge of the key players, those “ships” that dared to go out on the sea eleven years ago.

For an update on the status of the Paintbrush Factory and its closing, please see the following statement: https://www.facebook.com/FabricaDePensule/