Building Up and Breaking Down Walls of Our Own: An Interview with Paul M. Farber

This interview unpacks the making of Paul M. Farber’s book A Wall of Our Own: An American History of the Berlin Wall (University of North Carolina Press, 2020). More than just a Cold War travelogue shadowing the times spent by legendary American cultural figures Leonard Freed, Angela Davis, Shinkichi Tajiri, and Audre Lorde in Berlin during the second half of the twentieth century, the book interweaves history with critical visual analyses to draw comparisons and contrasts across national borders. The Berlin Wall itself becomes a protagonist in the book, which is a thoughtful meditation on physical, often monumental, manifestations of division in the past as well as today.

Ksenia Nouril: Your book A Wall of Our Own: An American History of the Berlin Wall presents a history of a specific time and place—a divided Berlin during the Cold War—through the lives of major American cultural producers. It does this primarily through the close analysis of images—photographs by the artists or of works by the artists, photojournalism, as well as personal snapshots. Can you take us back to the start of your journey in writing this book?

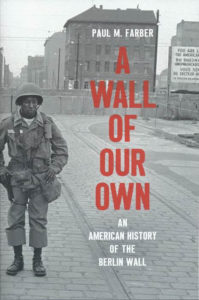

Cover of Paul M. Farber, A Wall of Our Own: An American History of the Berlin Wall (Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 2020)

Paul Farber: This book is an outgrowth of my dissertation in American Culture, which I completed at the University of Michigan. I went to graduate school in order to teach, write, and engage publics in social issues, especially confronting legacies of racism, sexism, and homophobia. A few weeks after I arrived on campus, I realized that I didn’t know what my topic was going to be but that I had to leave Michigan so I could get critical distance. In summer 2008, I went to Berlin and ended up living in Prenzlauer Berg, a few blocks away from Mauerpark, which was the unofficial memorial to the Berlin Wall and a site of memory. Coincidentally, a Leonard Freed retrospective had just opened at the C/O Museum in Berlin. At the same time, President Barak Obama, then a candidate, came to Berlin. Those two events set off all kinds of possibilities and questions. I realized that of all the artists and writers I wanted to think about—who had critically engaged American identity, American history, and American freedom—the one thing they all had in common was that they spent time in Berlin. Then I pondered that Berlin wasn’t firmly a trip “outside” of the United States, given the geopolitical history, the legacy of military occupation, and even the cultural afterlife of the Cold War. What I needed to do was follow in the footsteps of the artists and writers whose stories I was stumbling upon in the streets of Berlin.

KN: How would you characterize this book?

PF: I first thought about writing a book just about photographers, but then I thought about what it would be like to come up with like a roundtable for democracy and art. Whom do I want at that table? Leonard Freed, Angela Davis, Shinkichi Tajiri, and Audre Lorde. They happen to have a common experience of being American Berliners—in addition to so much more. But that table just keeps growing, in part because of the ongoing endurance of walls of division, but also because artists continue to resist and find ways to do so, with grace, with the force of reckoning, and with a renewed sense of the spirit of history at their fingertips.

Leonard Freed, Berlin, 1989/1990 (Estate of Leonard Freed/Magnum Photos)

KN: What is your relationship to the book’s main protagonists—your interlocutors, if I may?

PF: The grammar of belonging and location, social division and displacement are fundamental themes in this book. I wanted to play with that in part because I saw the protagonists of the book playing with it as well. And sometimes that was wordplay, but oftentimes, that was sincerely them coming to grips with what it meant to be American and the other intersectional identities that they embody. The book focuses on motion and movement, in part because I have found those themes to be ways of confronting and pushing against the status quo. But the book is also in opposition to the Berlin Wall. It’s in opposition to the heavy weights of history. It’s in opposition to binary thinking about the Cold War and the notion that history is linear.

Klaus Franke, “Angela Davis, East Berlin: Visits East German Border with West Berlin,” September 1972 (BArch, Bild 183-L0912-412)

KN: You are clearly bringing together two contexts that are disparate yet connected: that of Berlin and the United States in the Cold War period as well as that of race in the United States and abroad during this time.

PF: I wrote this book as a Jewish, queer, and white person, as a curator and a historian. I felt that in order to continue in the work that I do, which is around confronting the walls of division in the United States, physical and social, I had to go to the place that is among the heaviest in history for Jewish people, for queer people. I had to be able to see how trauma and transformation live side by side. The first time I went to Berlin was in 2004, when I was college student studying abroad.

KN: And what was that first encounter like?

PF: I grew up in a Jewish community that valued Old World roots. I knew several people who had gone back to Europe to try to find their family who had either perished in the Holocaust or had left to escape pogroms, but Germany was off-limits. Yet in Germany, I felt more comfortable being Jewish and queer there than I did anywhere else in Europe. And I thought, “If I’m feeling this as a Jewish and queer person here, what would one feel if one were Native American or Black American in what we now call the United States? Where would you go that isn’t tainted with as heavy a history for their people?” So, perhaps it’s not a question of rhetoric but a question of belonging. People from all around the world have found home in Berlin, a city once itself divided and in an identity crisis. While the protagonists I wrote about are thought of as some of the greatest thinkers on identity, they did not have fixed notions of identity. They had to, over time, understand the ways that identity formation is part of mass state projects, of violence and marginalization, and sources of self-actualization, growth, and care.

Dagmar Schultz, “Audre Lorde, Ika Hügel-Marshall und Dagmar Schultz vor der zerstörten Berliner Mauer [Audre Lorde, Ika Hügel-Marshall, and Dagmar Schultz in front of the destroyed Berlin Wall],” Audre Lorde Archive, John-F.-Kennedy-Institut für Nordamerikastudien, Freie Universität Berlin Archives

PF: I wanted to talk about the cultural history of Americans in divided Berlin. I wanted to see it from their eyes and understand their footwork as well. Each of the protagonists in the book are not simply living in an isolated level of West Berlin. In fact, all of them are interacting with the border Wall and the border system, more broadly. And for them and other people who come up in the book, like Paul Robeson or Nan Goldin, they are actually moving through East and West Berlin. I thought a lot about language, and so I try to refer to divided Berlin. At times I talk about this geographic area that had once been Berlin and would later become Berlin while other times I am talking about East or West Berlin as political entities. This kind of specificity of language is very important. In addition, I wanted to be aware of racial struggle in ways that I didn’t often see in American accounts of the Cold War, which make it seem like there was a good side and a bad side, a right side and a wrong side, without accounting for narratives of the U.S. as a hegemonic power with its own practices of racial apartheid. For example, while most of Leonard Freed’s photographs were taken in West Germany, including West Berlin, he had to drive through part of East Germany in order to get there, so I wanted to understand that process. In the early days of the Wall, he still was a foreigner from the West who has access to drive through East Berlin. I only found this out through the papers of his friend, the Dutch journalist Willem Oltmans. This was profoundly important in understanding what Freed was seeing. His single shot of a Black GI guarding the edge of the American Sector of West Berlin, days after the Wall first went up, at a time when he would be denied full citizenship rights in the U.S., beckoned Freed to seek stories of segregation through his work. (The image also is on the cover of the book.)

Leonard Freed, Berlin, 1961 (Estate of Leonard Freed/Magnum Photos)

KN: On multiple occasions, you talk about the East’s relationship to that Wall as a form of protection—a protection against West German Christianity, a protection against the saccharine corruption of capitalism and products like Coca-Cola. That’s a refreshing perspective when it’s usually the East that is demonized by the West. You reference Reagan-era politics and programs, such as the Strategic Defense Initiative known as Star Wars, aimed at protecting the United States with ballistic missiles. In the case of Berlin, you book draws out the signs, like when you recount Tom Brokaw’s telecast from the Wall on November 9, 1989, when Mauerpeckers (wall peckers) lost no time in chiseling away chunks of the Wall. It became very popular to own “memorabilia” —bits of the Wall—on proud display in one’s home or office.

PF: That’s a question I ask when I do public talks, like, “Who has a piece of the Berlin Wall? Where is it in your house?” Most people say, “It’s on the shelf or in the basement or I don’t know.” If you counted all those pieces up, you’d have enough to rebuild the Wall 10 times over.

KN: I imagine that most of the people who have pieces of the Wall today did not literally live in proximity of the Wall but figuratively lived on one side or the other, so the Wall for them became a symbol of something—oppression, freedom, etc. The pieces, thusly, become auratic, as if having a piece of the Wall can bring you closer to that authentic experience.

PF: Part of the goal of this book is to not treat the history as static but to understand its living force. The way to do that was to not merely rely on American narratives, and to really push against triumphalism. A great source for me was writing about the former Soviet Bloc, especially the work of Svetlana Boym in the book The Future of Nostalgia, which has a chapter on Berlin. For her, the goal of the researcher or the artist, or the engaged resident for that matter, is not to try to rebuild the city in any one way that claims authority over another, but to make sense of the gaps. From the first time I went to Berlin, I experienced a city full of presence and absence.

Leonard Freed, Berlin, 1961 (Estate of Leonard Freed/Magnum Photos)

As we’re talking about the notion of something being forever until it’s lost, it makes me think about the artist Adrian Piper, whom I met when I did the exhibition The Wall In Our Heads: American Artists and the Berlin Wall at the John B. Hurford ’60 Center at Haverford College in 2015. Piper left the United States and currently lives and works in Berlin. Her “Everything” series uses the phrase, “Everything will be taken away,” as a reminder that this is not forever, that the experience of loss is actually deeply a part of American history. Over the course of 2020—in the stories of the gaps, erasures, active dispossession, and displacement of narratives that don’t just celebrate White supremacy—you hear the echoes of people like Piper, who have been saying that for the better part of two decades.

KN: Agreed! Right now, every field, including Russian and Slavic Studies, is trying to reckon with history. Everyone is asking, how are we supposed to talk about race in the Soviet space? Stereotypically, it’s a very white field about a very white region, but it’s actually much more diverse—in the Soviet Union alone, 15 republics each with their own ethnicities and languages. Berlin, too, is quite the melting pot—I think the Germans describe it as “multikulti” or multicultural. In your book, Berlin is clearly a utopic, diaspora place—a nexus for transnationalism or non-alignment. How would you describe it?

PF: During the Cold War, Berlin was a place of refuge, an outpost, a center for culture. While I was interested in official state visits, those that were sponsored by the German Academic Exchange Service DAAD and by the US State Department, I was much more interested by those who went on detours, who went on their own volition, who turned physically in their own directions and lines of sight. I wanted to know what impact they had on a knowledge of the Cold War. Because I think the story of the Cold War and arguably other kinds of prominent chapters of history are so often told from the points of view of presidential and diplomatic papers, with art and culture as the background or the flourish. And I wanted to flip that, which is, in a way, to understand borders, separations.

KN: Let’s go back to borders. How did more recent border issues, like Trump’s wall at the US-Mexico border, factor into your thinking?

PF: I wanted the book to help readers understand borders, separation, as well as geopolitics from the point of view of the very people who are able to navigate the kind of rocky terrain of democracy and world progress. To see what barriers they faced, physically and socially, in their journeys. I hope that can offer insights on the larger structures that bind and block those who cannot move so freely, and on those who punish people seeking refuge rather than welcoming them.

KN: Speaking of progress, what are your next steps for the book, for your work moving forward?

PF: My work, in general, centers on walls and monuments. When I began this journey a decade and a half ago, I didn’t know that both were so intertwined—symbols within the same system. This process has also been bittersweet because for figures like Freed, Tajiri, Davis, and Lorde, vision and vulnerability were parts of their Berlin history. They were fascinated by the layers of history that lived in Berlin, and it gave them kind of a cipher to understand other sites of geopolitics. So I found myself toward the end of writing this book really wanting to know what they would say about contemporary Germany.

Through the course of my research, a new generation of artists, including Stephanie Syjuco, picked up the mantle, which I explored in The Wall in Our Heads. Their work was already pivoting to think about the legacy of Berlin vis-à-vis other sites of division, such as the US-Mexico border. So I ended this book also wondering whether that’s a book I would like to write, or a book I hope someone else will write. I’m really open to that latter fact. It would have to speak to the work of artists like Michelle Angela Ortiz or Ana Teresa Fernandez as well as the countless other figures who have pointed out through their work that walls are not natural. Walls are hateful and racist structures, which, one day, will be monuments to their own demise. Art helps us understand that and dismantle them, at least in our heads first.

Shinkichi Tajiri, The Berlin Wall, 1969–1970 (Shinkichi Tajiri Estate).

KN: How have you come to redefine “monument” as a result of this book?

PF: The first summer I lived in Berlin, a friend came to visit. One of the first things he asked was, “Can you take me to the Berlin Wall?” I immediately thought, “That’s a ridiculous statement. Here we are, nearly 25 years after the Wall has been dismantled. No, I cannot take you to the Wall.” But then I said, “Aha! Here are the places I could take you. I could take you a few steps from our apartment to Mauerpark, where there is a piece of the Hinter Wall. I can walk you a few steps further to Bernauer Strasse along the Cobblestone Trail that moves in and out of the city, that comes into existence throughout the city, marking the path of the former Wall. We could go for a bike ride on the Mauerweg, which is a bike trail throughout the city. And if we keep going, I can keep taking you to those places where the physical wall, or its kind of long shadow, still exists.” I realized that the question “Where is the Berlin Wall?” really sparked this whole project. That question also led me to the pieces of the Wall that had been displaced from Germany and replaced in American contexts as monumental structures, like the ones in the collection of the Smithsonian in Washington, DC. It’s not enough just look at a monument and ask what is represented. One must understand all of the forces that brought it there and what it either sheds light on or obscures. Pieces of the Wall that celebrate freedom and unconstrained movement of the Cold War are an interesting mirror through which to see or not see our own history. Rather than writing about it in the book, I taught a class about this idea in relation to monuments at the University of Pennsylvania, when I moved back to Philadelphia in 2012. This was the class that inspired my work on Monument Lab. So, in the end, the Wall—with all its constituent pieces stew across the world—is not a structure that could ever be put back together again but an assemblage that is pointing towards something entirely different.

KN: That’s very prescient.

PF: For me, that was the warning call for the moment we find ourselves in now, where there’s a large-scale reckoning and reimagining of monuments. For me, my first understanding of that came from seeing the legacy of the Berlin Wall represented in American public spaces. It’s not to say that we didn’t have a stake in it, or their important stories, right? It’s just that it was an emphasis. I’ll put it like this, in the city where was writing my dissertation—Washington DC—there were more pieces of the Berlin wall than there were statues to abolitionists.

KN: Could you share a final thought about this book within the context of your overall practice, as a historian, a public intellectual, a curator?

PF: I think of my work also as an assemblage. It’s, of course, about what I read, what I write, what I create. But it’s more so about relationships. It’s encountering spaces, people. It’s following in the footsteps, to use that word again, of others who I encounter and build with. So for me, the fundamental part of the way I see history and the way I see art is that it’s not something that can be thought of as isolated or even as personal. They’re fundamentally social and constantly evolving. Part of the way that I try to put that into play is to think of my work with artists or as an artist as part of the way to see the world and sense the world. It’s not art as ornamentation or artistic decoration. It’s art as the vital force to interact with the world. And, likewise, I think of history in the same way, situating my work in artists’ archives, filling the gaps between their public work and inner thoughts. I’m fascinated by what you can see through the perspective of artists asking some of the toughest questions that we have and will continue to ask about how we live with one another, how we deal with the weight of history, and how we can find pathways toward transformation. Deep down in all of this is a desire to balance the forces of what we’ve inherited, whether as knowledge, systems, or symbols, and understand how we leave our own imprint.