The 3rd Moscow Biennale of Contemporary Art (Exhib. Review)

The 3rd Moscow Biennale of Contemporary Art, Garage, Center for Contemporary Culture, September 24, 2009 – October 23, 2009

Over the last four years, Moscow’s audience has become accustomed to an extended range of international art exhibitions. These shows generally present a rather disorganized – often even misleading – view of current art production outside of Russia. The 3rd Moscow Biennale of Contemporary Art, with its mixed bag of works drawn from other international exhibitions, was no exception. With some 80 artists represented – among them Anish Kapoor, El Anatsui, Wim Delvoye, Sun Yuan and Peng Yu – , visitors recognized pieces that had appeared at many other recent international shows. As far as established Russian artists were concerned, the curator’s preference was for materiality, craft, and aesthetic enjoyment – criteria that were in perfect sync with the Russian national taste for collectible objets d’art.

Dmitry Tsvetkov’s elaborate installation Ice Age consisted of ironic taxidermy—including a stuffed bear, fox, and rabbit. All the animals were larger than life and each was dressed in elaborate fur coats, led by a blind mouse. The humanized poses of Tsvetkov’s animals brought to mind Bruegel’s, The Parable of the Blind Leading the Blind, which illustrates the noted parable phrase “And if the blind lead the blind, both shall fall into the ditch.” Tsvetkov’s reference seems appropriate, as the curator of the Moscow Biennale seems to have chosen artworks which work in contradistinction to the show’s theme. His inability to properly illuminate the exhibit’s ideology strands the patron, making it difficult for a visitor to understand the show’s underlying concerns.

Tsvetkov’s animals were displayed in the hangar of the Garage, along with artists from Europe, like Koen Vanmechelen. Vanmechelen brought several live chickens as part of his ongoing project Cosmopolitan Chicken, which is based on the cross breeding of hens. Celesté Boursier-Mougenot’s thirty stuffed sparrows were part of the installation, from here to ear -version .8 (2000). Bousier-Mougenot’s display also included guitar cases and amplifiers, brought together by the artist’s ambiguous logic. Here, too, Berlinde de Bruyckere showcased one of her signature works – a sculptural hybrid of a horse and a vegetable. In this company, Tsvetkov’s installation did not seem out of place and only added to the zoo-like scene on the floor. Whether such use of nature can be considered to be a valid trend inspired by Damien Hirst’s animal mummies, or merely just an attempt on the part of the curator to initiate a new vogue, is debatable. But whatever the reason, such a hodge-podge layout of gallery space felt over-loaded with objects, and seemed to go against coherent viewing.

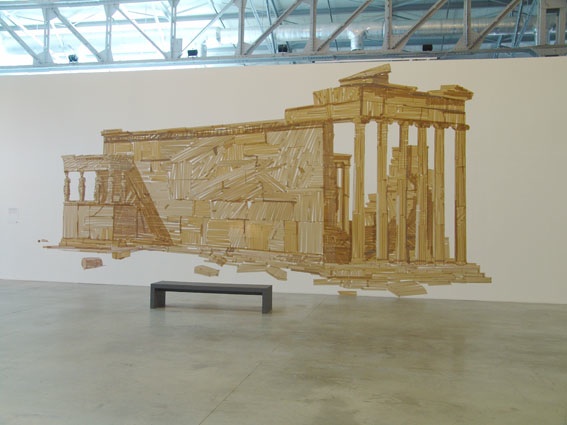

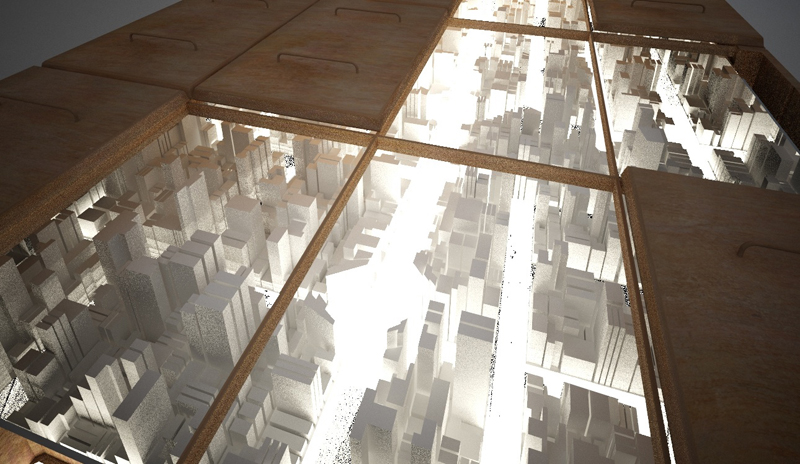

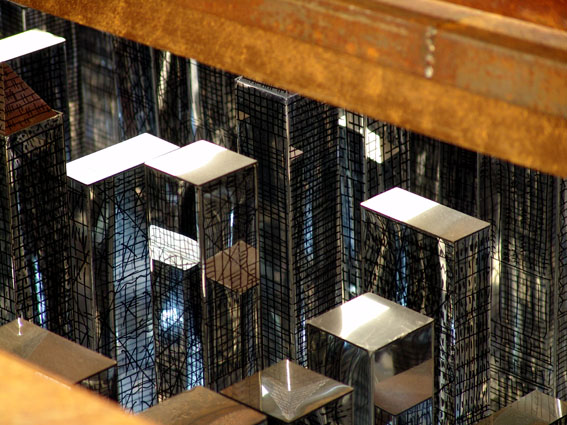

But perhaps curator Jean-Hubert Martin intentionally favored sculptural monumentality, as he knows Russia well, having curated the exhibitions, “Paris-Moscow” (1979) and Ilya Kabakov’s exhibition in 1985. After surveying the beginning of Moscow conceptualism with Kabakov in the 3rd Moscow Biennale, Martin focused on the second-generation of Moscow Conceptualists, such as Brodsky, Gutov, Osmolovsky, etc, by displaying their sculptural and painterly endeavors. On first appearance, Alexander Brodsky’s eight-meter long installation of a rusty welded mass of garbage containers looked awkward against the other carefully crafted exhibits. But his work also had a trick to it: inside the artist had placed a model of an entire city made out of mirrors. By playing on the contrast of the materials – ‘a pearl inside a casket’ effect – this installation entertained the viewers through its crafty and magical guise.

If Brodsky’s piece pulled towards the sublime, then the younger Russian artists pushed towards the ridiculous. An amateur artist Stas Volazlovsky, who is based in Kherson, Ukraine, and outsider-artist Alexander Lobanov, presented paintings that traded in a combination of current political comments and urban criminal folklore. Painted on fabric or dirty bed-sheets and stained with strong tea, the artists appropriated motifs derived from Russian folk pictures (lubok). By bringing together vulgar inscriptions, ornaments and images culled from newspapers, these works were intended to contest the glossiness of the rest of the show. Yet, themselves equally kitsch, these underground confessions only added to the all-embracive mood of the exhibition.

The biennial’s theme, “Against Exclusions”, was devised to introduce artistic geographies that Moscow had never seen before. Martin said that by taking this title he was able to present artists from Australia, Africa and India in an effort to counter the side effects of globalization such as racism and xenophobic violence that have contaminated Moscow.(Interview with Jean-Hubert Martin, by Max Seddon: https://www.artmargins.com/index.php/interviews/508-jean-hubert-martin-on-his-upcoming-moscow-biennale-interview) Martin was adventurous enough to introduce art from the African continent to Europe in 1979 during his exhibition “Magiciens de la terre”, but the art milieu has changed since then and the naïve paintings of Cyprien Tokoudagba, Chéri Chérin and Chéri Samba are no longer avant-garde. In fact, the works needed reinforcement that came from the sickly gilded three-meter tall head of an Indian goddess by Ravinder G. Reddy, which looked esoteric in contrast to other works. From a standpoint of exhibition logic these fusions between mass and traditional cultures clashed with the minimalist installation Silence of Images, by Alfredo Jaar, based on a political investigation. Pushing hard against exclusion, the curator seemed to pick a multicultural survey of Western ‘favorites’.

The biennial’s theme, “Against Exclusions”, was devised to introduce artistic geographies that Moscow had never seen before. Martin said that by taking this title he was able to present artists from Australia, Africa and India in an effort to counter the side effects of globalization such as racism and xenophobic violence that have contaminated Moscow.(Interview with Jean-Hubert Martin, by Max Seddon: https://www.artmargins.com/index.php/interviews/508-jean-hubert-martin-on-his-upcoming-moscow-biennale-interview) Martin was adventurous enough to introduce art from the African continent to Europe in 1979 during his exhibition “Magiciens de la terre”, but the art milieu has changed since then and the naïve paintings of Cyprien Tokoudagba, Chéri Chérin and Chéri Samba are no longer avant-garde. In fact, the works needed reinforcement that came from the sickly gilded three-meter tall head of an Indian goddess by Ravinder G. Reddy, which looked esoteric in contrast to other works. From a standpoint of exhibition logic these fusions between mass and traditional cultures clashed with the minimalist installation Silence of Images, by Alfredo Jaar, based on a political investigation. Pushing hard against exclusion, the curator seemed to pick a multicultural survey of Western ‘favorites’.

What was on par with usual Western standards was the biennial’s installation display and technical support. There was no question that “Against Exclusions” was most professionally installed within white walls and adjustable lighting. But this had a duplicitous effect. The sparkling light and the cased objects produced another meaning when they brought to mind an atmosphere of a big shopping mall. The cross-cultural fusion displayed on its floor reminded me of MALLticulturalism, a word used to describe both a shopping mall and a sweeping appropriation of other cultures, brought together to boost the local market. For the Moscow Biennale occasion, these objets de jure added flavor to a national vinaigrette of controversies–a conflict between the circle of Moscow conceptualists and those who follow neo-liberal trends last flared up when the Kandinsky Prize was awarded in December 2008.

If the Moscow Biennale exhibition failed to present a rigorous perspective on contemporary art, it fulfilled the role of an entertaining outlet. Younger spectators (the first post-Soviet generation) lined up outside the Garage, waiting ‘to taste’ a big international exhibition. (They would not remember that their parents queued outside the Pushkin Museum only two or three decades earlier to see the exhibitions from abroad). Hence, a general interest in art has not surpassed this generation, but the substance of the art has changed: it is now an object and a product of mass culture, engaging visual pleasures, and tantalizing emotions.

Not to complicate the viewing experience, Martin left out works that might provoke thoughts about political or social problems, and favored attractiveness and exoticism. Perhaps the lure of Reddy’s richly gleaming sculpture disturbed the Russian art critic David Riff, who described the whole exhibition as a paean to the magical side of art, its timeless essence, and an example of the neo-conservatism that has contaminated the Russian art scene. Riff also admonished the pursuit of craft and the emptying out of the conceptual stakes Russian artists, Osmolovsky and Gutov.

Not to complicate the viewing experience, Martin left out works that might provoke thoughts about political or social problems, and favored attractiveness and exoticism. Perhaps the lure of Reddy’s richly gleaming sculpture disturbed the Russian art critic David Riff, who described the whole exhibition as a paean to the magical side of art, its timeless essence, and an example of the neo-conservatism that has contaminated the Russian art scene. Riff also admonished the pursuit of craft and the emptying out of the conceptual stakes Russian artists, Osmolovsky and Gutov.

Not only did Russian artists take tactile qualities seriously, but others followed the demand for the attractiveness of objects. In reference to the thirteen, life-size wax figure installation Old Persons Home, by Chinese artists Sun Yuan and Peng Yu, Martin said “We are probably ruled by too many old people.” The installation featured the aged dopplegangers of world leaders, such as Yasser Arafat, Churchill or Mao, endlessly swinging in wheelchairs. They are long crippled and impotent, left to spend their last days in true geriatric style. The installation instantly echoed Tsvetkov’s grotesque animal procession by its hyper-realistic presentation and irony. Where did you lead your viewer, I ask this celebrated curator? Entertained with surfaces and scale, and with so many works crowded inside the Garage, Martin’s exhibition felt ironically empty.

For related texts, please see: Moscow Diary: What to Make of this Year’s Biennale (Article) and Jean-Hubert Martin on His Upcoming Moscow Biennale (Interview)