Ljubljana Biennial of Graphic Arts (Exhib. Review)

The 28th Biennial of Graphic Arts, International Centre of Graphic Arts (MGLC), Ljubljana, Slovenia, September 4, 2009 – October 25, 2009

The 24th Biennial of Graphic Arts (2001) was marked by important changes to the event’s concept and content. Specifically, it introduced the curatorial system and abolished the traditional understanding of graphic arts. This allowed the Ljubljana Biennial to catch up with current trends in the strongly diversified field of contemporary arts. As a result, the Ljubljana Biennial was entirely open; the only criterion used was that the works represented be reproducible, which is of course an extremely flexible criterion.

For its 28th edition – due to the specifics of the Slovenian cultural space as well as financial and spatial ‘starvation’ – the biennial was able to rely only on local curatorial powers, seeking partnership with several exhibition spaces in Ljubljana. It should be emphasized that partner galleries were completely free and independent in conceiving their projects for this exhibition – provided they didn’t deviate too much from the general context of the event.

Bozidar Zrinski, the artistic leader of biennial chose The Matrix: An Unstable Reality as the main motto of the program and the title of the main exhibition. The term ‘matrix’ exists in the world of graphic arts as a technical term, but here extends to reference the cult film trilogy, The Matrix, as well as a sense of a broader structure of the social environment inside of which life takes shape as an unstable, unpredictable given. In this context, art is understood, on the one hand, as a means to define a given reality (the matrix), and on the other, as an attempt to surpass or change this reality in order to shake its very foundations.

This definition categorically fits this year’s winner of the Biennial Grand Prize, the American artistic collective, Justseeds (Fig. 1.). The international jury, consisting of Katia Anguelova (Milan), Jota Castro (Brussels), Bassam El Baroni (Alexandria), Valeria Ibrayeva (Almaty), Kim Jyeong-Yeon (Seoul), Eha Komissarov (Tallin) and Julia Moritz (Leipzig), recognized an important potential for shaping a better, different society in the work of this decentralized collective dedicated to radical art and culture. Justseeds collective pursues the values of humanism through actions like putting up posters and engaging in other forms of activism in urban environments and on the Internet. While the presentation of their work is highly classical, consisting of an eclectic assemblage of posters, their aesthetic quality emerges from a level of engagement and commitment that succeeds in establishing an effective means of communication.

This definition categorically fits this year’s winner of the Biennial Grand Prize, the American artistic collective, Justseeds (Fig. 1.). The international jury, consisting of Katia Anguelova (Milan), Jota Castro (Brussels), Bassam El Baroni (Alexandria), Valeria Ibrayeva (Almaty), Kim Jyeong-Yeon (Seoul), Eha Komissarov (Tallin) and Julia Moritz (Leipzig), recognized an important potential for shaping a better, different society in the work of this decentralized collective dedicated to radical art and culture. Justseeds collective pursues the values of humanism through actions like putting up posters and engaging in other forms of activism in urban environments and on the Internet. While the presentation of their work is highly classical, consisting of an eclectic assemblage of posters, their aesthetic quality emerges from a level of engagement and commitment that succeeds in establishing an effective means of communication.

I must also mention the exhibition of contemporary art from South Korea in a venue entitled Cankarjev dom, After Gogo: A New Era of Korean Art. This exhibition represents a group of artists from South Korea born in the 1960’s who belong to the so-called post-gogo generation, named after disco clubs and distinctive for its mimicking of Western influences. This exhibition by eight South Korean authors, conceptualized by the curator Kim Jyeong-Yeon, found its way to Slovenia thanks to the initiative of Jeon Joonho, the Grand Prize winner of the 27th Biennial in 2007, to make room for his colleagues in lieu of presenting his own independent exhibition.

The parts of the exhibition located in the International Graphic Arts Center and in the Jakopic Gallery were the work of curator Bozidar Zrinski. Zrinski invited numerous galleries and curators working in Ljubljana to participate in the conceptualization of the main exhibition platform, including Alkatraz Gallery (Jadranka Ljubi?i?), Ganes Pratt Gallery (Petja Grafenauer), Kapsula Gallery (Tadej Poga?ar) and Škuc Gallery (Alenka Gregori? and Gülsen Bal). The accompanying program of the Biennial consisted of many discussions and workshops, including an exhibition of children’s graphics on the boulevard of Tivoli Park and in Pionirski dom, a salon of artists’ books, and an international exhibition of comic books entitled Greetings from Cartoonia, organized by Forum Ljubljana.

The aesthetic and ethical patterns established by modernism are nowadays faced with many difficulties in trying to maintain their general relevance. For this reason, the works at the biennial strive to question, and thereby oftentimes exceed, the criteria traditionally used to define graphic arts. The exhibition consequently represents a broad spectrum of artistic practices and displays a great degree of plurality on the level of form as well as content.

Approximately 80 artists from Slovenia and abroad are exhibited. Their works include graphic arts next to video art, artists’ books, installations, sound art, artistic magazines, photographs, graffiti, etc. The biennial by no means avoids classic graphic techniques, but rather inscribes them into an explicitly contemporary fine arts idiom.

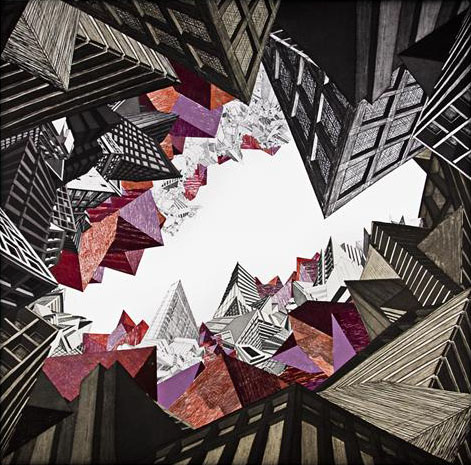

In the face of it all, one can’t deny the simple fact that most works are interesting, attractive and of high quality. Authors such as Vesna Drnovšek (Slovenia), Sameera Khan (Pakistan) (Fig. 2), Lee Chul Soo (South Korea), Nana Shiomi (Japan), Jelena Sredanovi? (Serbia) (Fig. 3), Swoon (USA) (Fig. 4), Nicola López (USA) remain dedicated to graphic arts – at the same time, graphic arts serve for them as a vast and inexhaustible testing ground for thinking about the world, about the everyday lives of people, and about one’s own intimacy and the questions of identity.

Many authors and works represented at the biennial focus on the specifics of urban space. In the series of graphics by Nicola Lopez (Fig. 5) we can identify elements of the urban landscape, used by the author in an attempt to use graphic arts as a means to re-create urbanity’s chaotic nature and sense of oversaturation. In the Skuc Gallery, Armenian artist Vahram Aghasyan (fig. 6) exhibits an interesting collection of posters with photographic images of a series of dilapidated bus stops in Armenia which, due to their experimental and pretentious architecture, have now resulted in something of an almost bizarre nature. Here, the matrix is exposed in the architectural criteria of functionality and design, but each set up turns out a bit differently, rendering each one unique, while the technological disposition of the whole series establishes a character of reproducibility.

The fact that the word ‘graphic’ remains part of the biennial’s name might seem misleading, even redundant, in the light of its revitalized program and content. Nevertheless, a more thorough contemplation of the artworks represented at the biennial legitimizes the continued use of the term. Hidden in the background of almost every work is a reference to some characterizing feature of graphic arts. In other words, while the works may not exactly fit into the narrow definition of classical graphic arts, they do use contemporary artistic discourse to simulate and question the distinctive qualities of this field.

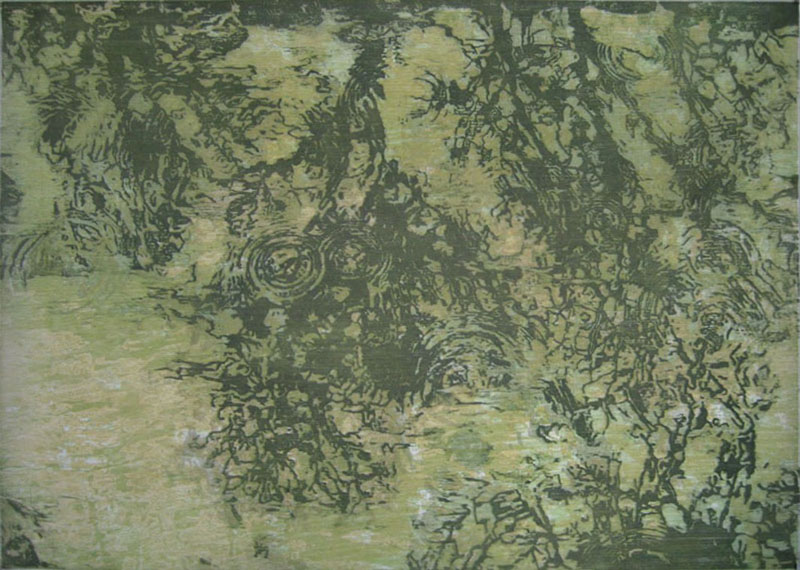

Of relevance to this discussion are two closely connected principles, both stemming from the ontological status of the graphic arts; seriality and diffusion. Two exhibited works, Envelopes (2008) by Croatian artist Marko Tadic (Fig. 7) and the cycle of miniature drawings by Jakup Ferri (Kosovo), are both extensive sets of simple yet intriguing haiku drawings that follow a free flow of associative thoughts and subconsciousness. On a formal level, they play around with the principle of seriality, a method of creation characteristic of representational graphic art which implies succession, different phases, re-runs or variations of its constitutive elements. Another example is the work of Slovenian artist Ksenija Cerce, who exhibits a collection of water patterns from different parts of the world in order to raise awareness about peoples’ often reckless attitudes towards this priceless asset.

Of relevance to this discussion are two closely connected principles, both stemming from the ontological status of the graphic arts; seriality and diffusion. Two exhibited works, Envelopes (2008) by Croatian artist Marko Tadic (Fig. 7) and the cycle of miniature drawings by Jakup Ferri (Kosovo), are both extensive sets of simple yet intriguing haiku drawings that follow a free flow of associative thoughts and subconsciousness. On a formal level, they play around with the principle of seriality, a method of creation characteristic of representational graphic art which implies succession, different phases, re-runs or variations of its constitutive elements. Another example is the work of Slovenian artist Ksenija Cerce, who exhibits a collection of water patterns from different parts of the world in order to raise awareness about peoples’ often reckless attitudes towards this priceless asset.

Unlike seriality, diffusion is a much more complex, unconstrained and wholly open principle that is tackled by artists in different ways. If the concept of reproducibility touches upon technical elements of an artwork, then the concept of diffusion exposes the more tangible effects of the reproductive process itself. For example, let’s consider mass-produced products from the world outside of the art world – diffusion is inscribed in their manufacturing mode. By way of artistic intervention, however, the diffusion is stopped and a mass-produced product becomes transformed into a unique and special object.

In his work, Feel Your Gravity (2005-), Japanese artist Taiyo Kimura (Fig. 8) cuts fashion magazines into pieces, thereby opening up new fields of perception and significance otherwise completely concealed from the surface of such an everyday, mass-produced item. Another variation of this strategy is the appropriation of reproducible products taken from the sphere of culture in its broadest sense, or even from particular art works, and their subsequent reinterpretation and re-launching into the field of large scale diffusion. We can see this in the video artwork, Love (2003), by Australian artist Tracey Moffat, in which the author re-edited a compilation of particular sequences from numerous films and made a new film which shows love in a different light.

In his work, Feel Your Gravity (2005-), Japanese artist Taiyo Kimura (Fig. 8) cuts fashion magazines into pieces, thereby opening up new fields of perception and significance otherwise completely concealed from the surface of such an everyday, mass-produced item. Another variation of this strategy is the appropriation of reproducible products taken from the sphere of culture in its broadest sense, or even from particular art works, and their subsequent reinterpretation and re-launching into the field of large scale diffusion. We can see this in the video artwork, Love (2003), by Australian artist Tracey Moffat, in which the author re-edited a compilation of particular sequences from numerous films and made a new film which shows love in a different light.

Finally, another procedure completely opposite to the two previously mentioned requires significant and unique input by the author. With the help of technology, or rather media, that make reproduction and thereby diffusion possible, this artistic input becomes accessible to a huge number of consumers – a work published in an artist book or in an art magazine, or broadcasted on an artistic radio network is an example of this strategy. In this way, someone’s unique and individual input becomes a matrix, transforming itself into a massively distributed item. An example is the work by Columbian artist Carlos Motta who, among other things, exhibited a publication actually printed in a newspaper, bearing the very straightforward title, A Brief History of Leftist Guerrillas in Latin America (2009).

Due to the fact that particular works deal with very specific thematic preoccupations, the 28th Biennial of Graphic Arts achieves an utterly heterogeneous effect in terms of content. Moreover, its concept deliberately allows for much room to maneuver. In its current form, the Ljubljana biennial comes across as a broadly conceptualized testing ground for the transference and transformation of various code systems where the artists present themselves as well as the specifics of the environment in which they find themselves situated.

This combining and experimenting with different contexts achieves the effect of a “parody of insecurity”, to quote Turkish artist Ahmet Ogut’s witty description of his own work. And when artists make the world visible and translucent, when they position the world inside such a parody of insecurity, they start gnawing away at its monolithic nature. But when utopian idealism crashes into reality, it seems that exposing this world for what it really is all too often falls within the boundaries of what is acceptable and harmless. The Ljubljana biennial is no exception, and in this sense raises numerous questions – what kind of concrete effects can an artwork still produce, what is its actual power in the contemporary world and to what degree can it still be dangerous?