The 14th International Architecture Exhibition of the Venice Biennale

Fundamentals, the 14th International Architecture Exhibition of the Venice Biennale, June 7 – November 23, 2014.

Fundamentals, the title of the 14th International Architecture Exhibition of the Venice Biennale (June 7 – November 23, 2014), experimented with new approaches. First, it ran longer than past exhibitions, for almost six months instead of three. Secondly, it was organized according to a tripartite formula, with the first section, Monditalia, highlighting Italy, and occupying one third of the conceptual component of the exhibition that also included other media, such as dance and theater. The second, Absorbing Modernity 1914-2014, was held in the Giardini’s permanent pavilions, featuring additional national exhibitions located throughout the labyrinthine space of the Arsenale and throughout the city itself. For this section of the exhibit, participating nations were asked to present their pavilions in consideration of how they had been impacted by modernity over the last 100 years. More accurately, the theme explicitly asked participants to consider: “How has modernity been “absorbed,” a phenomenon that, at least within the context of the exhibit, was understood as the gradual effacement of national styles and the encroachment of a more universal language of architecture.

Inside the Giardini’s National Pavilions, general view. Photo by the author.

But as Rem Koolhaas, curator of the exhibition, indicated, the idea of a “modernity absorbed” should not necessarily be seen as positive or as a process of “grateful acceptance.” Rather, it should be evaluated with the same gravity that a “boxer absorbs a blow.”(1) Certainly the allusion to a boxer’s punch carries with it a wealth of associations, implying, perhaps, a certain kind of passivity. More so, it may be interpreted as a powerful visual image of violence being performed, or rather, as a trauma incurred and occurring with the frame of the spectacle.

Koolhaas’s reductive question for the national pavilions also functioned as a prompt meant to engage with the main theme of the third part of the exhibit, Elements of Architecture, held at the central pavilion. This section took as its focus the building blocks of architecture (even though agency and the architect were notably and purposefully absent from this section): walls; windows; toilets. Kohlhaas’s question yielded multivalent results revealing a host of exhibition strategies from the pavilions of Eastern Europe, their fractured pasts and, in particular, the divergent national histories that drew attention to the complexities of this year’s Biennale. For the purposes of the discussion, I have selected a small group of national pavilions within Eastern and Central Europe that, specifically due to particular historical and political circumstances, represent complex examples of the tension between the international goals of the Biennale, and the local and national reactions to “problems” of modernity.

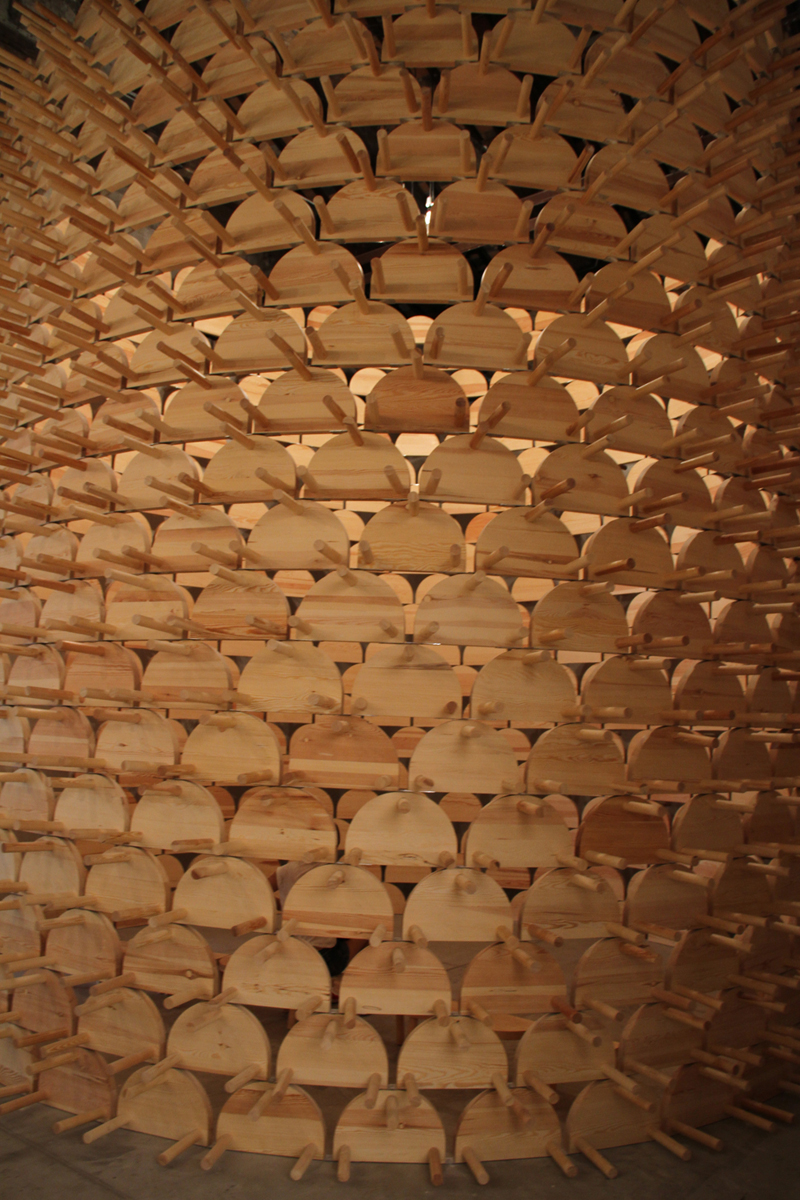

Pavilion of the Republic of Kosovo, “Shkambi Tower,” wood installation, 5 m x 5.5 m. Photo by the author.

The pavilions that touched on these and other relevant issues include the small and unassuming space occupied by the Republic of Kosovo’s installation in the Arsenale, a three-part exhibit entitled Visibility (Imposed Modernity) featuring a tall tower of almost 700 three-legged vernacular wooden stools turned outward and stacked high to the ceiling and arranged to create a smooth circular interior space. This basic structure, the stool, served not only as an independent part of the exhibit but also as an interactive and connective element, the very means of accessing the third part of the exhibit, a wall opposite the tower, displaying illustrated postcards. Generally, the purpose of a postcard is to call attention to, and to remind one of, pleasant experiences in the context of new surroundings, and yet, within the exhibition, the familiar postcard – arranged as a moveable mosaic of history – is given a new context and meaning, invoking the power of memory to new ends. The postcards of images and architectural drawings of structures (religious and domestic) ranged from different periods of Kosovo’s history, and were made available both for one’s visual consumption and for selection and removal, according to the visitor’s tastes and aesthetic inclinations. The result was not only the potential for one’s own carefully curated personal collection, but the gradual disassembly of a larger whole by collective action. Two main parts of the exhibit came together to create an alternative engagement with both the theme of fundamentals and the question of modernity as it is applied to national identity by creating “visibility” and emphasizing the destructive qualities of an “imposed modernity” on traditional modes of building. The fixed tower built from a traditional and largely unchanging unit to create a quiet contemplative space strikes a contrast to what may, at first, seem like another immutable fundamental or “wall.” Yet, it is a wall whose transformed surface became the locus for an animated process of flux and even confusion as visitors either waited patiently for their turn to arrange the postcards, boldly reached around others, or shuffled back and forth to find more cards. Kosovo’s exhibition was a commentary on tradition, foreign consumption, as well as the material past and its erosion defined as an ongoing process. As the exhibit states, it is a “cry to help preserve what is left.” The exhibition then served as a finger pointing to the damage done to traditional modes of building and made visible the erasure of past modalities of living extended to its present.

Pavilion of the Republic of Serbia,“14 -14.” Photo by the author.

The Republic of Serbia’s exhibition, entitled 14-14, employed two simultaneous narratives, playing with light and dark, and with memory and ideas of what was, and what never was, constructed. Included on the interior walls of the pavilion were plans of 100 buildings once highly regarded in their time, illuminated by skylights and the warm tone of the pavilion’s interior walls. Juxtaposed against a sense of optimism and success, was the unrealized project initially designed by Vjenceslav Richter in 1961, known as the Museum of the Revolution of Yugoslav Nations and Ethnic Minorities. In a darkened vestibule, a documentary focused on the site of its proposed construction, today a voided landscape located within the urban fabric of Belgrade. Since only the foundations wereever built, the site hovers between abandonment and a source of underground shelter for the houseless and marginalized.

Romanian Pavilion, “Site Under Construction.” Photo by the author.

Although the Romanian pavilion called attention to urban ruins, now considered eyesores to the contemporary population, it allowed some consideration of their future potential. However, these ruins resist any kind of romantic nostalgia and, thus, are unlike the ruins that once served as the playgrounds or sites of projected fantasies, such as the Grand Tourists who once traveled through the Mediterranean. Rather, these are “heavy ruins” that call attention to a host of complex issues that have more to do with the realities that faced many nations between 1914-2014, such as the loss of economic self-reliance, global inequity, political instability and environmental challenges. Although the Romanian exhibit offered no definite answer to the question of how these ruins might one day become reactivated, it is somewhat difficult to envision what the future of these factories might be, and even more difficult to imagine them as museums. Limobuso ir limuzino nuoma su vairuotoju

Romanian Pavilion,“8h Shift.” Photo by the author.

FOOTNOTES

- Excerpt from a video interview by dezeen: http://vimeo.com/98420617. [back]