Paulo Bruscky & Robert Rehfeldt’s Mail Art Exchanges at Chert Gallery, Berlin

Cold War Domestics—Home Archives: Paulo Bruscky & Robert Rehfeldt’s Mail Art Exchanges from East Berlin to South America and Signs Fiction: Ruth Wolf-Rehfeldt at Chert gallery, Berlin, January 10 – March 28, 2015.

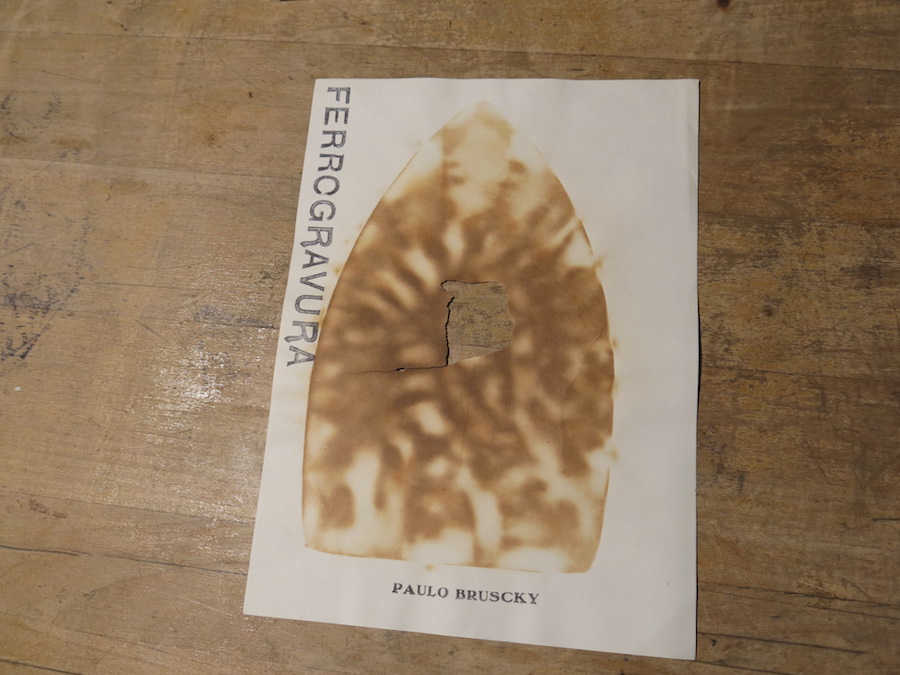

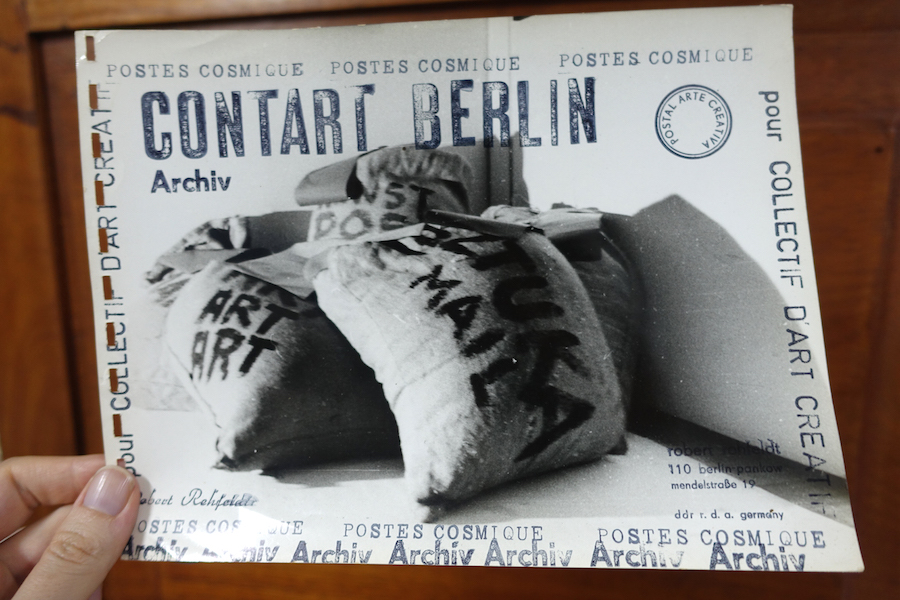

Over sixteen years of a committed artistic collaboration organized and almost entirely mediated by the mail, Brazilian artist Paulo Bruscky (b. 1949) and East German artist Robert Rehfeldt (1931-1993) exchanged materially modest, if conceptually bold, artworks to overcome immense physical and political obstacles. Crossing 5,000 miles and two repressive Cold War-era regimes, their mail art often trucked in slogans and icons that were at once immediately identifiable and laden with artistic metaphor and ingenuity. Bruscky’s Ferrogravura (iron engravings) —the brown burn of a hot iron on paper—are innovations in domestic printmaking that reveal the artist’s humor, as well as a necessity for resourcefulness and creativity in a country governed by military rule. Rehfeldt responded to comparable conditions in East Germany, and maintained, like Bruscky, an earnest and idealistic confidence in art’s capacity to speak and redefine universal languages. In his East Berlin atelier, he stamped out the slogans of his “contart” (contact + art), dropping in the mailbox a vision for socially engaged culture: “ARTISTS OF ALL COUNTRIES UNITE;” “MAKE A CREATIVE WORLD NOW;” “KUNST IM KONTAKT IST LEBEN MIT DER KUNST” (ART IN CONTACT / IT’S LIFE IN ART).

Both artists are well known within their geographic and media canons. Bruscky, an artist still active in Brazil today, is also famous for his performance art and public actions, works that, like his mail art, highlight the important role an audience plays in the meaning-making of art. Rehfeldt worked primarily in mail art, but is also credited with East Germany’s first performance art piece (Ich bleibe in der DDR [I am staying in the GDR], 1953). He also worked with Super-8 film and video, and is considered one of East Germany’s most influential experimental artists.

Central figures in the global mail art network, Bruscky and Rehfeldt corresponded with each other between 1976 and 1991. A rare look at this exchange was on display at Chert gallery in Berlin. Home Archives curators Zanna Gilbert, postdoctoral fellow in the Department of Drawings and Prints at The Museum of Modern Art, and artist David Horvitz have intimately arranged dozens of documents in this small and unusual space. In the absence of much introduction or contextual intervention, viewers come upon these artist communiqués as if the gallery were a neatly exploded mailbox, or “home archive” as it were.(For more detail on Rehfeldt/Bruscky from the curators, see: Zanna Gilbert, “The Human Letter: Mail Art Exchanges between East Berlin and Northeast Brazil in the 1970s,” Fillip, no. 20 (Spring 2015); Matteo Mottin, “Expanded | Home Archives. Chert, Berlin,” interview with Zanna Gilbert and David Horvitz, ATP Diary, January 11, 2015, http://atpdiary.com/exhibit/expanded-home-archives-chert/.) The exhibition presents a sizable selection of the mail Rehfeldt received from Bruscky, organized thematically by genre and recurring motifs along long tables, on walls, or in vitrines. Bruscky’s Homework pieces explore a deliberate naiveté, which, placed next to a series of photographs titled The Fallen Wall intimate a more profound message, namely a sensitivity toward Rehfeldt’s East Berlin environs.

The curators’ choice to install a series of “automatic drawings” generated from EEG-scans of Bruscky’s brain (My Brain Draws Like That) in the gallery’s highest reaches emphasizes that privacy and ineffability formed part of the artist’s practice. Rehfeldt’s working table sits heavily in a corner beneath these jagged drawings, both a mise-en-scène for the postal collaboration on display and a memorial for a man with an immense and highly mythologized importance for several generations of East Germany’s artists. His contributions appear in the exhibition by proxy. A whirring slide projector casts images from Bruscky’s Rehfeldt archive in Brazil at 15-second intervals. The contrast in presentation underscores the singularity of the East German artist’s style, which tended to use more text than Bruscky, often in multiple languages. Ironically, it was reportedly difficult to communicate directly with Rehfeldt. Though burdened with a stutter since a childhood accident, the greater obstacle seems to have been his insistence on answering phone calls in languages other than German.(Wolfgang Leber, “Gruß an einen Mailartisten ohne Antwort – Der Grenzgänger Robert Rehfeldt” in Robert Rehfeldt. Kunst im Kontakt, Lutz Wohlrab, ed. (Berlin: Wohlrab Verlag, 2009), 18.) The curator’s choice to keep this work an ocean away honors the spirit and material realities of a unique artistic collaboration, whose distance likely enabled a more intimate engagement on Rehfeldt’s part. Aside from one pivotal visit Bruscky made to East Berlin in 1982, the artists’ friendship was entirely mediated through and by the post.

Though the letters are ordered, that is to say curated, Home Archives nevertheless feels a bit like happenstance, mirroring its curatorial team’s own introduction to the Bruscky/Rehfeldt correspondence. A few years ago in Recife, Gilbert’s doctoral research led her to Rehfeldt’s missives, catalogued carefully in Bruscky’s enormous mail art archive. Across the world in Berlin, Horvitz, a mail artist himself, visited Rehfeldt’s home archive of artwork correspondence where he saw Bruscky’s end of this exchange.(In the intervening time, Horvitz has also begun sending Rehfeldt’s widow, Ruth Wolf-Rehfeldt, mail art and is now included in her archive. One of these works is modestly displayed without a label in the Home Archives exhibition.) Both Gilbert and Horvitz were taken with the depth of this friendship recorded in years of communication. Home Archives reflects the seductive challenge of translating traces (pieces of mail, smudges of ink, bent and torn envelopes) to understand a bond.(Horvitz in “Expanded,” op. cit.: “When I was looking at Bruscky’s work, it was on Robert’s old work table. There were smudges of ink on the table from years of using rubber stamps. I thought this was nice, this layer of ink on the wood, like a palimpsest, attesting to this life-long commitment to a creative practice. It was like someone’s life, all that time, collapsed into smudges of ink.”) Likewise, the decision to keep the archives apart reflects the curators’ cross-continental processes of finding and gathering this information, an experience that parallels in part the distances Bruscky and Rehfeldt overcame through their mail art to each other.

Though the letters are ordered, that is to say curated, Home Archives nevertheless feels a bit like happenstance, mirroring its curatorial team’s own introduction to the Bruscky/Rehfeldt correspondence. A few years ago in Recife, Gilbert’s doctoral research led her to Rehfeldt’s missives, catalogued carefully in Bruscky’s enormous mail art archive. Across the world in Berlin, Horvitz, a mail artist himself, visited Rehfeldt’s home archive of artwork correspondence where he saw Bruscky’s end of this exchange.(In the intervening time, Horvitz has also begun sending Rehfeldt’s widow, Ruth Wolf-Rehfeldt, mail art and is now included in her archive. One of these works is modestly displayed without a label in the Home Archives exhibition.) Both Gilbert and Horvitz were taken with the depth of this friendship recorded in years of communication. Home Archives reflects the seductive challenge of translating traces (pieces of mail, smudges of ink, bent and torn envelopes) to understand a bond.(Horvitz in “Expanded,” op. cit.: “When I was looking at Bruscky’s work, it was on Robert’s old work table. There were smudges of ink on the table from years of using rubber stamps. I thought this was nice, this layer of ink on the wood, like a palimpsest, attesting to this life-long commitment to a creative practice. It was like someone’s life, all that time, collapsed into smudges of ink.”) Likewise, the decision to keep the archives apart reflects the curators’ cross-continental processes of finding and gathering this information, an experience that parallels in part the distances Bruscky and Rehfeldt overcame through their mail art to each other.

The aesthetic of these letters is decidedly cluttered, and often imprecisely wrought with stamps, typewriters, and makeshift at home materials. The artists usually chose symbolic communications over the complex, preferring more immediate messages, which emphasized connectivity, in particular art’s function as a social conduit. Whether interpreted individually as discrete works or en masse, the Bruscky/Rehfeldt exchange emphasizes the fundamental equality and necessity of sending and receiving a message. Both artists were dedicated to using art to strengthen human-to-human contact, which, in the geopolitical conflicts under which their friendship grew, enacted a kind of citizen agency outside the reach of two oligarchic states. Bruscky’s mail art emerged as an alternative artistic language that soughtto both evade state surveillance and the trappings of ideologically motivated art making. Rehfeldt, working in a country that valued art’s prefigurative ethical function, emphasized the realism of the everyday and the immediate through his “art in life” philosophy. Both wanted to exceed geographic context and take part in a global artistic conversation.(The range of their correspondence reflects the success of these ambitions. Among a long list of pivotal figures, both corresponded with Ray Johnson in New York and Rehfeldt enjoyed a strong German-German bond with Joseph Beuys.) By engaging in a global mail art network, Bruscky and Rehfeldt contributed to a community of artists who embraced a nonhierarchical approach to art making and display that emphasized the importance of the everydayness and accessibility of art. Though mail art was most often exchanged privately, exhibitions, summits, and publications also fortified and expanded these transnational communications.(A call for participation from Paulo Bruscky and his mail art collaborator in Brazil, Daniel Santiago, inviting artists to participate in the First International Out-Door Exhibition in Recife in January 1981, as well as plans for a similar exhibition in 1978, are installed on one of the gallery walls. Both calls indicate that all artists who submit the proper materials would be included.) In the case of Bruscky and Rehfeldt, mail art also enabled otherwise impossible exchanges. Because for a time neither artist could visit the other’s country, their messages acted in part as self-representations, messages that could narrow the geographic and political distances that kept them apart.

Working within idiosyncratic national contexts of material privation and bureaucratic absurdity, both Bruscky and Rehfeldt innovated methods to circumvent, underscore, or even highlight these conditions without submitting to them. For example, both artists’ use of the rubber stamp—with its overtones of officialdom—deliberately engaged the languages of their oppressors to invert and defang this power. Bruscky’s “envelope poems” are here particularly germane. On one envelope, the profile of a Native American is attached to the outline of a male torso stamped internally with a red bleeding heart, an added signification that reflects Brazil’s indigenous and European identities and histories. The man speaks Rehfeldt’s East German address. This, the only text on the envelope to be written in long hand, appears framed in a speech bubble, interrupted by the stamp of two hands shaking in agreement. A whimsical butterfly renders the nearly imposing text “FELIZ” (happy) that appears in the envelope’s upper left at once sincere and ironic. Bruscky frequently uses human figures, animals, and objects to soften the intentionally mechanical tone of his stamped out communications. The remainder of the envelope’s text vacillates somewhat between the bureaucratic and the artistic. The smearing stamp of “IMPRESSOS” (printed matter) could be either the hasty work of a post office employee or a Bruscky addition that compliments his “MAIL ART” message and the even more inconspicuous “ARTE VIA AEREA” (Art via the air, or simply, Air-art). A square blue diamond is ambiguous, perhaps a visual cue to the postal workers processing this letter from Recife on September 26, 1977. Bruscky’s visual poem indeed acknowledges the hands that will hold his letter before it would arrive to its intended East Berlin recipient. His confidence in art’s ability to connect and impact its audience then expands in service of his selected medium, namely the mail in and of itself. Meanwhile, the screen-print images of hishead on the inside of some of these envelopes are literally covert arrivals accessible only to Bruscky’s intended recipient.

Working within idiosyncratic national contexts of material privation and bureaucratic absurdity, both Bruscky and Rehfeldt innovated methods to circumvent, underscore, or even highlight these conditions without submitting to them. For example, both artists’ use of the rubber stamp—with its overtones of officialdom—deliberately engaged the languages of their oppressors to invert and defang this power. Bruscky’s “envelope poems” are here particularly germane. On one envelope, the profile of a Native American is attached to the outline of a male torso stamped internally with a red bleeding heart, an added signification that reflects Brazil’s indigenous and European identities and histories. The man speaks Rehfeldt’s East German address. This, the only text on the envelope to be written in long hand, appears framed in a speech bubble, interrupted by the stamp of two hands shaking in agreement. A whimsical butterfly renders the nearly imposing text “FELIZ” (happy) that appears in the envelope’s upper left at once sincere and ironic. Bruscky frequently uses human figures, animals, and objects to soften the intentionally mechanical tone of his stamped out communications. The remainder of the envelope’s text vacillates somewhat between the bureaucratic and the artistic. The smearing stamp of “IMPRESSOS” (printed matter) could be either the hasty work of a post office employee or a Bruscky addition that compliments his “MAIL ART” message and the even more inconspicuous “ARTE VIA AEREA” (Art via the air, or simply, Air-art). A square blue diamond is ambiguous, perhaps a visual cue to the postal workers processing this letter from Recife on September 26, 1977. Bruscky’s visual poem indeed acknowledges the hands that will hold his letter before it would arrive to its intended East Berlin recipient. His confidence in art’s ability to connect and impact its audience then expands in service of his selected medium, namely the mail in and of itself. Meanwhile, the screen-print images of hishead on the inside of some of these envelopes are literally covert arrivals accessible only to Bruscky’s intended recipient.

Rubber-stamped messages likewise emblazon nearly all of Rehfeldt’s works, both as central elements and as their supplements. In one piece projected onto Home Archive’s back wall, the text “DADA IS DEAD / CONTART LIVING IN YOUR MAILBOX” appears in large, evenly spaced block letters. Three additional stamps accompany Rehfeldt’s proclamation: a framed “ACTUAL POST” confirms the paper’s category, the circular “POSTAL ARTE CREATIVA” recalls a post office stamp of origin, and a serif-script font reading “Robert Rehfeldt” approximates the artist himself. With all three either askance or in another ink color or font, these stamps resemble official approvals added by another—even several—authorities, and mimic the look of a mailed envelope. That Rehfeldt’s signature appears a second time in pencil at the base of the image at once adds a human touch to this work and also distances the artist from the stamped signature that fades into the upper right corner. He doubles his presence here, while also emphasizing his dependency on the mechanics and approximations that he had to use in order to connect with Bruscky.

Not to be overlooked is the role that Rehfeldt’s wife, Ruth Wolf-Rehfeldt, played in this cross-continental story. Also a mail artist, she worked on a smaller, more meticulous scale than her husband and was less invested in the conceptual networking practice of mail art as a communicative conduit to other artists.(Anne Thurmann-Jajes, “Robert Rehfeldt and Ruth Wolf-Rehfeldt. Their GDR-Based International Network,” setup4, no. 1 “Artists’ Publications” (2013), http://www.setup4.de/ausgabe-1/themen-und-beitraege/anne-thurmann-jajesrobert-rehfeldt-and-ruth-wolf-rehfeldt/#_ftnref14.) Wolf-Rehfeldt was nevertheless instrumental in keeping the couple’s network of artists organized. Meticulous index cards cataloguing contacts and correspondence appear copied and installed as wallpaper in Chert’s second entryway gallery space.

Not to be overlooked is the role that Rehfeldt’s wife, Ruth Wolf-Rehfeldt, played in this cross-continental story. Also a mail artist, she worked on a smaller, more meticulous scale than her husband and was less invested in the conceptual networking practice of mail art as a communicative conduit to other artists.(Anne Thurmann-Jajes, “Robert Rehfeldt and Ruth Wolf-Rehfeldt. Their GDR-Based International Network,” setup4, no. 1 “Artists’ Publications” (2013), http://www.setup4.de/ausgabe-1/themen-und-beitraege/anne-thurmann-jajesrobert-rehfeldt-and-ruth-wolf-rehfeldt/#_ftnref14.) Wolf-Rehfeldt was nevertheless instrumental in keeping the couple’s network of artists organized. Meticulous index cards cataloguing contacts and correspondence appear copied and installed as wallpaper in Chert’s second entryway gallery space.

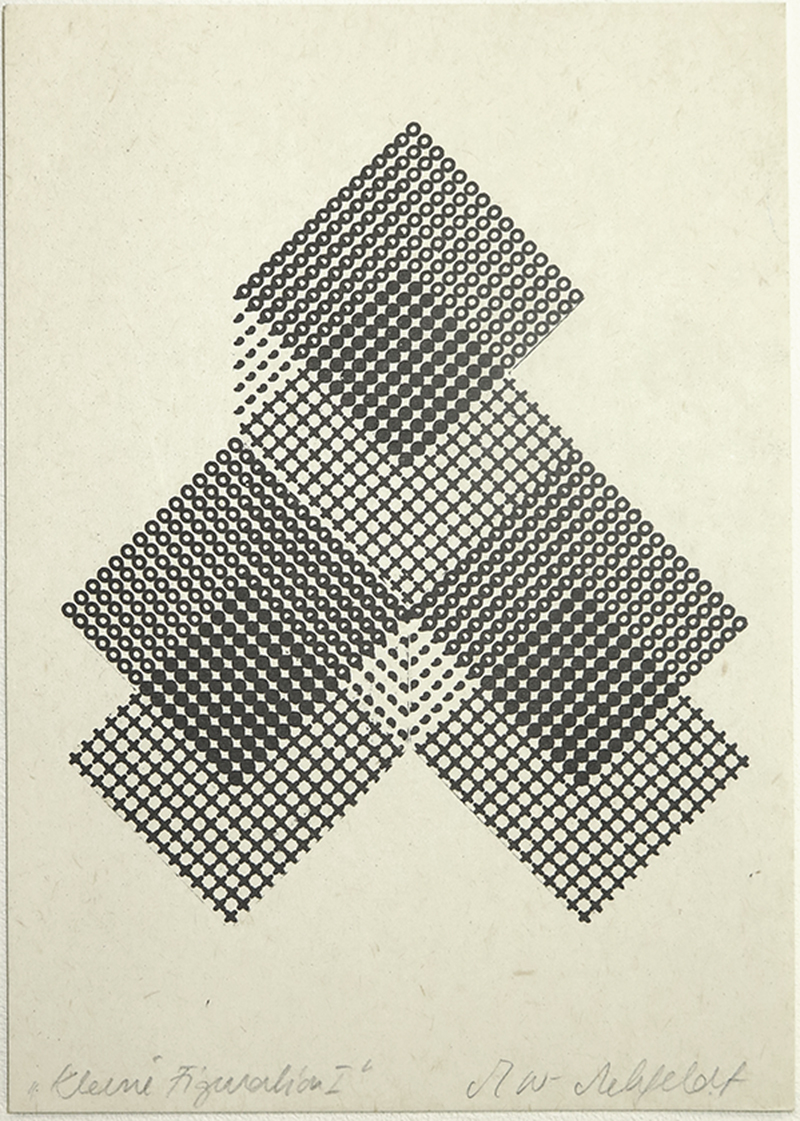

In a parallel exhibition Signs Fiction, gallerist Jennifer Chert presents a fascinating selection of Wolf-Rehfeldt’s typewriter poem postcards. The small-format works render type into three-dimensional space, sometimes simply graphic, sometimes more objectively referential, and often composed from words: “ARTMOSPHERE,” “TO,” “FROM,” “GEDANKE” (thought). Wolf-Rehfeldt’s hand, translated into typewriter, is precise and hypnotic, a fine combination that illustrates her attentions to the international languages of minimalism and other orderly postmodernisms of her contemporaries both within and beyond the East Bloc. The visual poems are quite still as compared to the next room’s hastier rhythm, and offer a second simultaneous example of Cold War artistic production. These two exhibitions connect more fundamentally in the intimacy and domesticity of the works on display. These artworks stand out not only in their historical markings, that is, as documents of a previous era, but also in the commitment they maintain to the simplest, or most foundational, artistic ambitions: to communicate, to explore, to self-represent, to make art, as Rehfeldt would say, “trotzdem“—nevertheless.