Three Years: Retrieval of the Lost Generation of the Romanian Neo-Avant-Garde

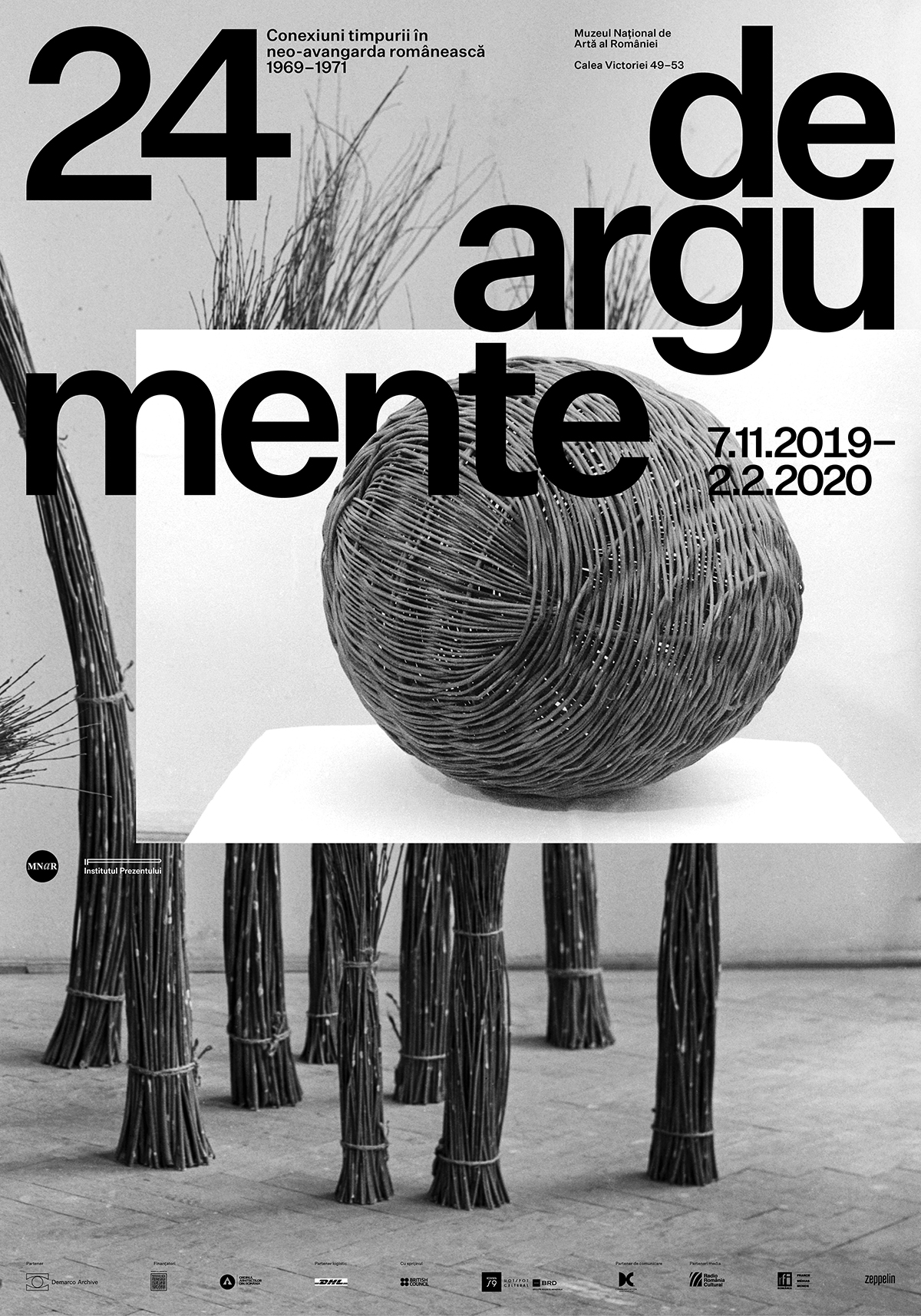

24 Arguments: Early Encounters in Romanian Neo-Avant-Garde 1969–1971, The National Museum of Art of Romania, November 7, 2019–February 2, 2020

While writing this article on an exhibition tracing cross-cultural relations between Romania and the United Kingdom, free movement and transnational and translocal exchanges have become, during the current pandemic, luxuries of a past epoch. The exhibition under review, 24 Arguments: Early Encounters in Romanian Neo-Avant-Garde 1969–1971, recounts the cultural exchanges that took place during the three short years identified, which now loom in historical distance. In these far away times, just a few years after Ceaușescu came into power in 1965, he started his reign as a progressive non-aligned and West-friendly leader, who condemned the Warsaw Pact invasion of Czechoslovakia in 1968. During this brief and almost forgotten period of Romanian art, artists could gain international prominence through official and semi-official channels of cultural diplomacy.

Exhibition poster series featuring Pavel Ilie’s Object, 1971 and Twigs, 1971. Sculpture, wickers. Image courtesy of Institute of the Present. Photograph by Eugeniu Lupu. Poster design by Andrei Turenici.

The exhibition focused on the collaboration between the Richard Demarco Gallery in Edinburgh, Scotland, and the Romanian artists Horia Bernea, Ion Bitzan, Liviu Ciulei, Radu Dragomirescu, Șerban Epure, Pavel Ilie, Ritzi Jacobi, Peter Jacobi, Ovidiu Maitec, Paul Neagu, Miriam Raducanu, Diet Sayler, Radu Stoica, Vladimir Șetran, and The Sigma Group. This is the first exhibition project of the Institute of the Present conceived by the editor and cultural manager Ștefania Ferchedău and the art historian Alina Șerban in 2017. Institute of the Present is a self-organized initiative based in Bucharest, which publishes an online magazine as well as a series of print publications, and organizes lectures, workshops, conferences related to the research of the history of visual and performing arts in Romania from a transnational and transcultural perspective starting from the late 1960s. Their project is a master example of transnational art history writing,(On the usage of transnational versus translocal see Cristian Nae, “Networking the Bloc: Experimental Art in Eastern Europe 1965–1981” ArtMargins Online, November 26, 2019, https://artmargins.com/networking-the-bloc-experimental-art-in-eastern-europe-1965-1981-book-review/. In the case of this project the term transnational seems still adequate since the problem of national representation is at the heart of this case study.) which has emerged as a promising approach that goes beyond nationally defined and center-dominated art histories of Eastern Europe. It aims attention at cultural translation and the transfer of ideas, people, and artworks as a dialectical rather than a top-down process. Such agents as Richard Demarco become key figures of new art histories of the region grounded in the research of key events and networks.

Exhibition view with Ritzi Jacobi and Peter Jacobi’s Ileanda, 1974. Cotton, goat and horse hair, wool, coconut fiber and sisal. Viktor Oppenheim Haus Collection. Image courtesy of Institute of the Present. Photograph by Camil Iamandescu.

Installed in two spacious marble-covered halls of the former Royal Palace, which was transformed in 1950 to house the Romanian Museum of Art, swishing mobile sculptures Sigma Group and meandering jazz tunes from screened films evoked the cultural times, but without a superfluous nostalgic intention. The curatorial text states that the exhibition proposed a new working format, that of the exhibition-file, i.e. more simultaneous structural and thematic layers that included in addition to artworks, timelines, quotations, publications, and other documentary materials which the viewer was free to navigate and draw their own conclusions. Based on thorough research conducted in the archive of Richard Demarco, the Edinburgh-based artist and art producer, exhibition organizers Alina Șerban (curator) and Ștefania Ferchedău (artistic director) gathered an impressive range of works that were either originally presented in the exhibitions organized by Demarco or closely related. Consequently, the exhibited artworks do not represent anything more particular than the local versions of the cutting-edge trends of the 1960s, as their authors did not exhibit together in Romania nor did they belong to one artistic circle or generation.(Some graduated from the Art Academy in Bucharest while others (Horia Bernea, Șerban Epure, Diet Sayler) got engaged in art through informal channels and self-education. Demarco’s program and well as the 24 Arguments exhibition also included the theatre play of the actor, director, and stage designer, Liviu Ciulei and the dance performance of Miriam Răducanu. Some had just started their careers in the late 1960s such as Radu Dragomirescu and Radu Stoica, whereas others were also young but already established artists by then, such as Stefan Bertalan, who was the founding member of Group 111 (1965-69), the first community for experimental art in Romania, before he created Sigma Group with Constantin Flondor and Doru Tulcan, or Ion Bitzan or Vladimir Șetran, who participated in several international biennales from the mid 1960s.) Some artists, however intriguing their works, are rarely discussed today, such as Pavel Ilie, who created photo performances and environments composed of oversized biomorphic wicker objects, and Radu Stoica, represented in the exhibition by works on paper featuring a constructivist-conceptual version of Pop imagery. At the same time, artists Horia Bernea, Ovidiu Maitec, Ion Bitzan, and Paul Neagu, who all pursued very different pathways—from spiritual traditionalism to gestural abstraction to tactile art—today have their works in the collections of the most renowned museums of the world.

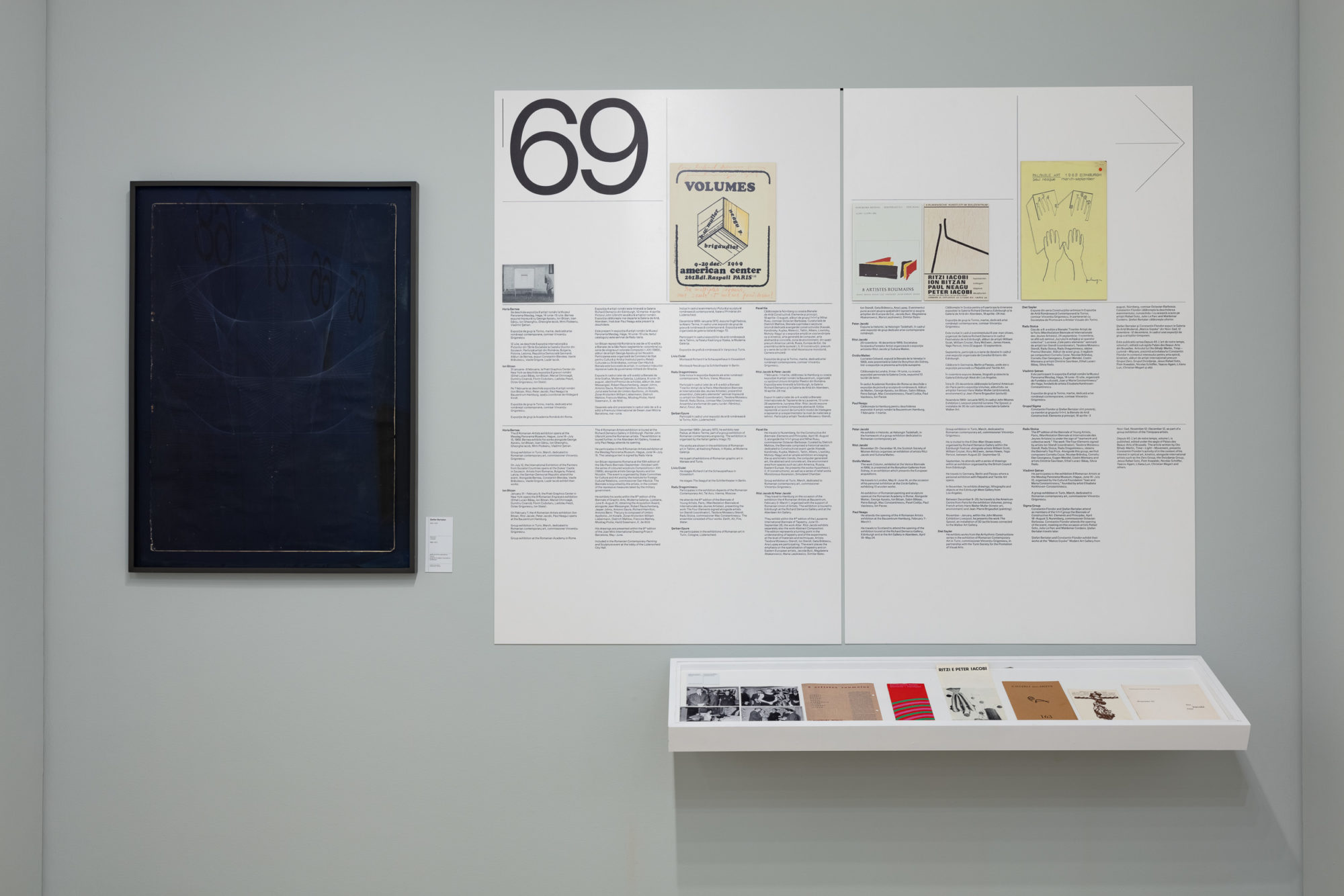

Exhibition view. Left: Ștefan Bertalan. Untitled, 1969-1970. Graphite on paper mounted on cardboard. Ovidiu Șandor Collection. Right: Section of the exhibition timeline Trips: International context. Image courtesy of Institute of the Present. Photograph by Serioja Bocsok.

The curators prepared two parallel and illustrated timelines to contextualize the displayed artworks and documents. The timelines span 1965 to 1971, a period defined by a relative liberalization and opening up of the Romanian art scene. During this time, international contacts were developed through state institutions as well as through personal channels established at international art events, such as the Paris Biennial of Young Artists, which were the catalysts for international networks and nodes that in retrospect can connect many parallel local narratives of neo-avant-garde. The exhibition’s first chronology, Trips: International Events, lists the travels and exhibitions of the presented artists to the West and to other parts of Eastern Europe, coupled with Ceausescu’s diplomatic travels during the same years. Thus, we can imagine a web of many parallel movements and encounters not only westward, which has a special importance as it confronts the common perception that East European artists were only interested in the “free” art of the so-called “capitalist countries.” Even more important is that such well-defined case studies demonstrate that the art scenes of Eastern Europe were not homogeneous in either space or time.

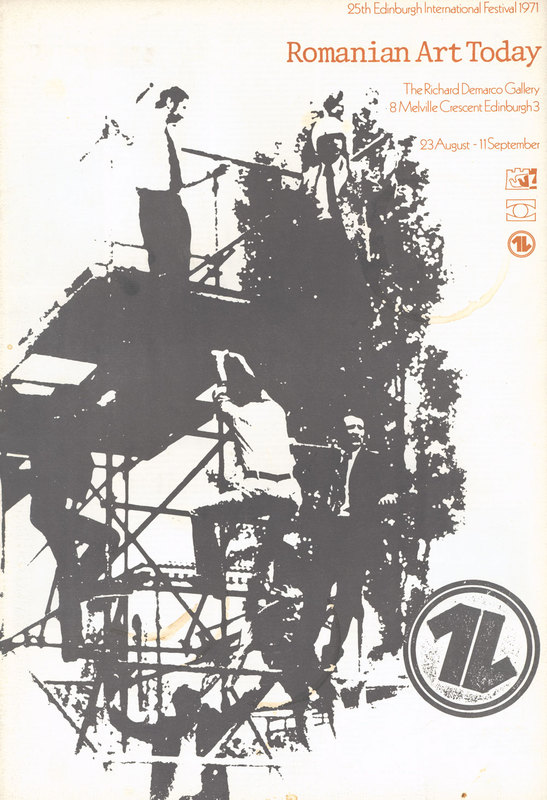

Whereas the first chronology gathers multiple actors and directions among which the Edinburgh exhibitions organized by Demarco were just one of several meeting points, the next timeline, Context: Romanian Art Today, was a more teleological narration of transnational cultural events that played a role in internationalizing the Romanian cultural scene. These include the traveling Henry Moore exhibition (1966-67) that was an inspiring event in many East European countries, and Demarco’s many visits to Romania that culminated in the exhibition Romanian Art Today in Edinburgh in 1971. The compromises and controversies(We learn from the timeline that the exhibition opened right after the conservative turn in cultural politics so in order to avoid the cancellation of the show Demarco had to include five more rather traditional artists (not featured in the 24 arguments exhibition), and problems with the transportation also caused that some artists in Demarco’s selection were only represented by photo reproductions.) of this large-scale event featured as part of the Fringe section of the Edinburgh International Festival and organized in collaboration with the Romanian Union of Artists signaled the decline of this open and progressive period after which many protagonists of this story left Romania.(Ștefan Bertalan from Sigma Group left in 1986 to Germany, Liviu Ciulei to US in 1980, Radu Dragomirescu to Italy in 1973, Șerban Epure to the US in 1980, Pavel Ilie to Switzerland in 1977, Peter and Ritzi Jacobi to Germany in 1970, Paul Neagu to the UK in 1970, Diet Sayler to Germany in 1973.)

Enriched by quotations and summaries of exhibition reviews (by critics Georges Boudaille, Radu Varia, and Cordelia Oliver), the chronologies are supplemented by catalogs, posters, and photo documents. The latter shows interesting shifts from diplomatic to informal situations, like finely dressed men and women sitting on the floor of the Demarco Gallery watching the dance performance of Miriam Răducanu, part of an accompanying program of the Romanian Art Today exhibition in 1971. From this point of view, the exhibited artworks and films illustrate the chronologies, but the exhibition also works vice versa, i.e. presenting vibrant artworks contextualized by documents and timelines.

Cover of Romanian Art Today catalogue, 1971. Richard Demarco Gallery. Vladimir Șetran archive. Image courtesy of Institute of the Present.

Even if the organizers restrained from taking a biographical approach by applying, instead, the methodology of exhibition history and focusing on the many actors and factors at play within a particular art event, the specific attitude of Demarco deserve some attention. Demarco opened his gallery in 1966 and visited Romania in 1968 (both Bucharest and Constanța). Instead of being lured by the “otherness” of the works of Romanian artists that was emphasized by almost every exhibition review in the Western press,(For instance Edward Cage’s article quoted in the wall text “Refreshing Works from Romania: A revelation” published in The Scotsman states: “in contemporary idioms, they differ most from the technologically spoilt artist of the West in the materials they use […]. These they transfigure into an aesthetic experience which is the richer for its humble origins.”) Demarco stressed the European fraternity between Romanian artists and those working in his own country, seeing both as integral to the cultural sphere of European art. His enthusiasm for not only Romanian artists but also Polish and Yugoslavian artists, who he also presented in Edinburgh, not only derived from his breadth of view, but also from his utopian, pedagogical concept of art having an agency in society, which resonated well with East European artists. His charismatic personality, however, does not overshadow the actual artistic practices brought to the foreground by the exhibition.

The case of the Richard Demarco Gallery also sheds light on the “grey zones” and “double speak”(I believe that this term—employed for instance by Edit Sasvári and Sándor Hornyik in Edit Sasvári, Sándor Hornyik, and Hedvig Turai, eds., Art in Hungary 1956–1980: Doublespeak and Beyond (London: Thames & Hudson, 2018)—could be effective in the transnational or comparative accounts of East European art scenes only if used in terms of an explicit strategy for addressing different audiences and horizons of expectations and not as a synonym of opportunism, as a moral condemnation of actors affiliated with different spheres of culture.) between the so-called official and non-official art in state-socialist countries. Demarco explored the art scene in Romania in collaboration with the Romanian Union of Artists and the State Committee for Art and Culture even if he showcased neo-avant-garde works, which might seem to not conform to a homogenized concept of socialist-realist art.(As described for instance in Maria-Alina Asavei, “Rewriting the Canon of Visual Arts in Communist Romania,” (Master Thesis in History, Central European University, Budapest, 2007): pp. 21–9. http://www.etd.ceu.hu/2007/asavei_maria.pdf Ileana Pintilie’s book Actionism in Romania During the Communist Era (Idea, 2002): p. 9 also situates actionism in Romania as a definitely dissident, underground practice isolated from but synchronic with international artistic phenomena and contrasted with “the dogmatic official position” but she also points out double roles.) Documents prove that especially between 1965 and 1971, the Artists Union was oddly interested in exporting neo-avant-garde artworks to the West as stated by Ion Grigorescu: “There was this tacit understanding: in your workshop you can do what you please, and even show your works to some strangers. With that you entered a new category. People like Richard Demarco, introduced to this duty-free shop of the Union by the new management, gave the green light to a trend of foreign currency + (sic) trips abroad, achieving a production mode that was something in between socialism and capitalism.”(Ion Grigorescu, “A Child of Socialism,” Plural, no. 2 (1999): p. 74. https://www.icr.ro/uploads/files/126651a-child-of-socialismion-grigorescu.pdf) More precisely, the transfer from diplomatic exchanges to presenting progressive art in its own right was made possible by artists such as Ion Bitzan and Ovidiu Maitec, who could collaborate well with both the state-socialist institutions and by such actors as Demarco who was interested in conceptualism and performance. Bitzan taught at the “Nicolae Grigorescu” Art Academy in Bucharest, participated in exhibitions serving political representation with a David Hockney-style realism with socialist propaganda imagery, and was also engaged in conceptual experiments compatible with the international art world. They are not the only ones in this group who could successfully speak more “artistic languages.” It can be stated that the artists who participated in the exhibitions at Richard Demarco Gallery either emigrated after 1971 or could cooperate with some layer of the cultural establishment.(Ovidiu Maitec, was in the Romanian Pavilion in 1968, 1972 and 1980. Vladimir Șetran participated in several exhibitions aiming at political representation. Horia Bernea was not only in Klaus Groh’s 1972 Aktuelle Kunst in Osteuropa, but also represented Romania in the Venice Biennial in 1979 and 1980.)

Exhibition view with works by Ovidiu Maitec, Ritzi Jacobi & Peter Jacobi, and Ion Bitzan. Image courtesy of Institute of the Present. Photograph by Serioja Bocsok.

To entangle these delicate distinctions, dedicated viewers could read for hours in the exhibition space; nevertheless, the powerful the effect of the works themselves were not diminished by this thorough contextualization. The first hall is dominated by Peter and Ritzi Jacobi’s monumental tapestry Transylvania III (1973) made of horse and goat hair. The couple, who had already left Romania by the time of Romanian Art Today exhibition, gained recognition in the late 1960s both in Romania and in Western Europe with their collaborative abstract textile reliefs using traditional and modern fibers. Here and in their work Ileanda (1974), expressive graphic qualities turned into sculptural texture loom midway between tactile informel, warm decoration, and topographical referentiality. Other highlights in this section include Ovidiu Maitec’s hand-carved wooden sculptures assembled on a low and wide platform that propose an ingenious interlanguage between traditionalism and modernism. Maitec, founding member of the Artists Union and author of monumental socialist realist public sculpture, made a swift international career with his mobiles and hinged works with movable parts exploiting negative space. Translation between object and image, multisensual experience, morphological gesture, and geometric abstraction define Ion Bitzan’s playful group of works on paper from 1970-71 displayed here, as well as his six-meter-long woodcuts, Cordonnet bien tendu and Cordonnet non tendu (in the background of the photo below featuring Miriam Răducanu’s performance), both from 1971. Also on view in this same gallery was a super-8 film of Paul Neagu’s 1971 Edinburgh performance, Horizontal Rain, showing Neagu—the most well-known artist in the group and the originator of “palpable art”—wearing his “Anthropocosmos” costume with many small pockets and walking on stilts. The film evokes the performative and ritualistic impulses originating from Neagu’s self-anthropological approach(Neagu mentions as an inspirations for his edible installations both folklore rituals as well as such urban, modern and international spells as the alphabet pasta: Paul Neagu interviewed by Mel Gooding (1994), (National Life Stories: Artists’ Lives, British Library ref. C466/27/05), p. 114. http://sounds.bl.uk/File.aspx?item=021I-C0466X0027XX-ZZZZA0.pdf) that had great appeal with Edinburgh audiences.

Paul Neagu. Cake Man Event, 1971. Exhibition view. Courtesy of Paul Neagu Estate (UK) & Ivan Gallery, © Paul Neagu Estate & DACS 2019. Photograph by Serioja Bocsok.

The exhibition’s second room was divided into sections devoted to individual artists. Here, it became clear that the artists promoted by Demarco did not belong to one movement, but rather were engaged in a broad range of practices without any evident common stylistic denominator. One could find examples for lyrical abstraction in the work of Horia Bernea and for geometric abstraction represented by Diet Sayler, kinetic and Op Art by Serban Epure. Performative and environmental practices most relevant for contemporary art discourses were also present, but these were the ones that were the most difficult to restage without getting distanced by the museum’s display. For example, Neagu’s “palpable art” (which was also participatory and edible at occasions) that enthralled the Edinburgh public – as visitors could touch his suspended objects in a dark room, and eat the particles of his “cake man” – could only be approached in the exhibition through concept sketches and films. The collective, educational practice and monumental outdoor installations of The Sigma Group were represented by documents, mock-ups and two mobile reconstructions.(In 2015 Alina Șerban curated a large-scale exhibition with a display architecture more reminiscent of the Sigma Group’s constructions: Sigma Group: “Cartography of Learning” 1969–1983, Art Encounters, Timișoara, 2015. https://2015.artencounters.ro/exhibit?q=Cartography&lang=en See also Alina Șerban’s article “Sigma Group: Negotiating New Spaces for Art,” Third Text 32, no. 153 (2018): pp 485–99.) The experimental, kinetic environments of Șerban Epure and Diet Sayler were also displayed through film and photo documents. Likewise, Pavel Ilie’s environments—exploring the art object’s dimensional, geometric and structural relation to the human body and the natural environment—could be viewed through sketches and photo documents. This why the dance performance Genesis, by the choreographer Miriam Răducanu reinterpreted and performed several times during the exhibition by Mădălina Dan, had a special importance in recuperating the performative aspects of the conjured art events.

Miriam Răducanu. Genesis, 1970 with Ion Bitzan’s Cordonnet bien tendu and Cordonnet non tendu, 1971 in the background. Performance, 7 min. Music by Anatol Vieru, reinterpreted by Mădălina Dan. Exhibition performance. Image courtesy of Institute of the Present. Photograph by Ștefania Ferchedău.

Despite this heterogeneity the curatorial text suggests that the exhibition “investigates the existence of a common spirit that defined this generation of artists.” What constituted this common spirit? One reviewer of the original Romanian Art Today exhibition phrased the crux of the show rather bluntly as “rewarding and virile folk art.”(Edward Gage, “Demarco Stages Rewarding and Virile Folk Art,” The Scotsman, August 30, 1971.) Is it truly their “foreignness” that distinguished these artists at their international participations? The Jacobi duo describes a consciously self-exoticizing strategy: “We tried to maintain the specific atmosphere of our culture and the objects we created don’t have a foreign feeling, they possess a local spirit.”(Ritzi Jacobi & Peter Jacobi, excerpts from the interview published in Arta magazine, no. 4, 1970.) The obscure, mysterious appeal of Neagu’s iconography was also the leitmotif of his Western reception. However, it seems that in the case of the above artists, as well as that of Maitec, Bernea, and Ilie, archaism and the use of traditional materials and techniques were employed as an intellectual strategy and not derived from any kind of naive or amateur identification. Rather, these artists demonstrate a critical approach to the opposition between the idea of national art—peculiarly cherished by the state-socialist cultural discourse in East European countries—and internationalism of the avant-garde, as well as to their international presentations framed by national labels.

Exhibition view with works by Pavel Ilie. Projects, 1970-1971. Photographs, exhibition copies. Eugeniu Lupu, Pelmuș Collections, National Galleries of Scotland, Richard Demarco Archive Collection. Image courtesy of Institute of the Present. Photograph by Serioja Bocsok.

This problem of the national framing of East European art, which was by no means a unique phenomenon, has already been raised by Piotr Piotrowski in connection with the Romanian exhibitions at Richard Demarco Gallery, among other exhibitions. Piotrowski connects this to “an interesting tension between the international rhetoric of communist ideology, and the national formula of communist art, to be seen primarily in the subject matter of paintings and architectural details. The unofficial inter- or transnational art exchange resulted in the nationalization of modernism in the Eastern Bloc countries.”(Piotr Piotrowski also states that “the nationalization of the avant-garde was the price of its appearance in the West,” “Nationalizing Modernism: Exhibitions of Hungarian and Czechoslovakian Avant-garde in Warsaw,” in Beyond Borders: Artistic Exchange in Communist Europe (1945–1989), ed. Jérôme Bazin, Pascal Dubourg Glatigny, Piotr Piotrowski (Budapest: Central European University Press, 2016): pp. 211–17.)

Yet, it cannot be taken for granted that both the artists and Demarco shared the exoticizing approach expressed in press reviews of the time period. It is more probable that such framing was to win the support of the Artists Union and that—as Klara Kemp-Welch has pointed out—was refined by the short interviews in the exhibition catalog, in which artists could self-define their specific relationships to “Romanianess.”(Klara Kemp-Welch quotes some replies of the artists that reveal their more or less reflected relationship to the national labels applied to their art, “Edinburgh Arts” in Networking the Bloc: Experimental Art in Eastern Europe 1965-1981 (Cambridge: MIT Press, 2019): pp. 244–45. It should also be mentioned the West European artists also presented their works under such titles as “15 British Artists” at sever occasions.) It is also telling that when Demarco organized a large-scale exhibition of Yugoslavian artists, Aspects ‘75 , considerations of cultural diplomacy also played a role, and so-called “primitive artists” had to be included. Nonetheless, Raša Todosijević’s famous text, Edinburgh Statement (1975) written for this occasion did not aim its wry criticism on the national framing of his participation, but on the capitalist art world that commodifies art.

Sigma Group. Mobile Ensemble, 1970-2015. Reconstruction, aluminium plates, nylon thread, fan. Exhibition view. Triade Foundation Collection. Image courtesy of Institute of the Present. Photograph by Serioja Bocsok.

On the other hand, there are several artists in the 24 Arguments exhibition, most clearly Șerban Epure, Diet Sayler, and The Sigma Group, who were involved in neo-constructivist, structural-geometric, and kinetic experiments totally devoid of rural and primitivistic undertones, yet they still impressed international audiences equally. Abstraction in many East European countries was regarded as a territory of freedom immune to political appropriation, as well as a commitment to modernism never independent from its political support or incrimination. Accordingly, I believe that it would be anachronistic and conceited to identify the underlying ethos of these practices in their new and alternative interpretation of locality and means of cultural transfer between national and international contexts. Since none of the artists was interested in using their art for explicit political statements, it is probably more adequate to grasp their consonance in the crisp and earnest authenticity, the air of self-empowerment and self-proclaimed freedom that withstands evaluation from a contemporary point of view, and does not flatten into sheer historical document or illustration.