New approaches to art and life in the Polish People’s Republic: Henryk Stażewski at Muzeum Sztuki

Henryk Stażewski (1894-1988) had a long artistic run in two different versions of his home country: first as a pioneer of the avant-garde in the Polish Republic between 1918 and 1939 and then his later, but no less experimental career in the communist Polish People’s Republic founded in the post-war world order after 1945. It is the latter that is the subject of the exhibition Henryk Stażewski: Late Style at the Muzeum Sztuki Lodz – to many known as a legendary institution with a pedigree as an avant-garde museum (including the colorful interior of the Neo-Plastic Room for abstract art) whose existence overlaps Stażewski’s long career.(See the website for the exhibition, https://msl.org.pl/henryk-stazewski-late-style/.) Curated by British design historian David Crowley, a leading specialist in Polish art under state socialism, the exhibition aims to investigate how an established figure of the avant-garde met the challenges of being an artist in the socialist state and remained a force of constant experimentation and new collaborations.

We might know single artist shows (or “monograph exhibitions”) as a mass-medium presenting popular artists with a focus on the most well-known aspects of their art and life, typically highlighting the formative years and the canonical masterworks. Exceptions include exhibitions that instead focus on overlooked and marginalized artists whose careers collided with trends in contemporary art, such as recent exhibitions of Leonora Carrington, Niko Pirosmani, or Hilma af Klint in Nordic art museums.(Leonora Carrington, ARKEN Museum, Copenhagen 2022; Niko Pirosmani, Louisiana Museum of Modern Art, Humlebæk 2023; and Hilma af Klint: The Ten Largest, Moderna Museet Stockholm 2022.) It is a much less popular approach to follow the late career of an artist, especially when it takes place in the dreary context of a communist state, far from the celebrated avant-garde times of the roaring 1920s and dramatic 1930s with exhibitions of the wonders of socialist industry in Wroclaw instead of artistic circles in Paris. But that is the theme of Henryk Stażewski: Late Style, which covers four decades of work starting from when the artist was in his fifties and was mostly limited to the Polish People’s Republic. With this topic, it is not a monograph exhibition as most. There is, however, no sense of quiet retirement or conformism. The dynamic late career of Henryk Stażewski never has a dull moment and opens the door to a burgeoning Polish art world, which to the international art audience is still one of the better-kept secrets.

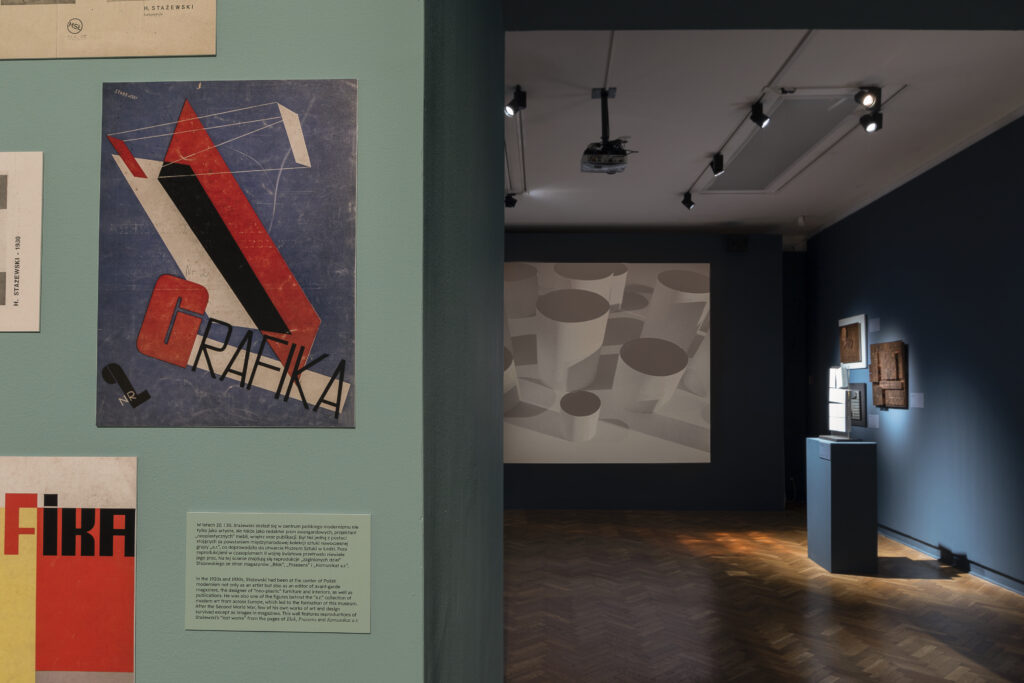

Henryk Stażewski: Late Style, exhibition view, Muzeum Sztuki, Lodz. Photo: Muzeum Sztuki.

The works exhibited include paintings defined by their geometrical clarity, which with surprising ease unify avant-garde and socialist art in their depiction of construction workers. A series of primary structures in bright color schemes, produced only a few years later, sees the artist experiment with space and system in a manner reminiscent of the neo-concrete movement. Following on from this phase, the exhibition focuses on works that draw on conceptual devices, along with sketches for environments, and color designs for new spaces. While a good portion of these works is defined by the style of colorful geometrical abstraction, there are also many surprises and experiments that draw on new practices of conceptualism and underground culture.

Henryk Stażewski: Late Style, exhibition view, Muzeum Sztuki, Lodz. Photo: Muzeum Sztuki.

In a conceptual gesture, the exhibition is structured around the age of its protagonist at the time of significant events. The first room is marked “56 Years and 1 month in 1950” – the artist’s age at a time when the full program of socialist realism had been imposed. On the other end “94 Years, 5 months, 1 Day” marks the age of the artist at his death in June 1988 – just a few months before the end of the Polish People’s Republic. These two years frame his “Late Style.” Apart from giving an apt illustration of the mature phase of the artist, the exhibition reflects on how the life of the artist was connected to the surrounding world and the ways in which art unfolds in various environments across generations and political borders. There is no time line of biographical events to guide viewers, which gives an impression that Stażewski was connected to the moment and its contexts in many ways, so that his biography could not be separated from the works. That said, an accompanying publication taking us further into those moments and contexts would have been a welcome addition, if not for the exhibition itself, then for the interest it creates.

The exhibition is displayed across the small rooms of the Muzeum Sztuki’s old building (MS1). Evoking the conditions of Stażewski’s career, this can create the impression of fitting greater schemes into smaller frames of the historical condition, also as most of the works are in smaller formats and the larger is represented in media documentation. Despite some lively colors on the walls and direct form and color schemes of these works, the impression of the exhibition is narrative rather than immersive, giving insight into the context rather than creating sensory stimulus here and now. There are great moments and a colorful rhythm throughout the exhibition, from the original “constructivist realism” paintings at the beginning to the almost psychedelic color-rooms further in.

Henryk Stażewski: Late Style, exhibition view, Muzeum Sztuki, Lodz. Photo: Muzeum Sztuki.

A member of the first Polish avant-garde groups, from cubism to constructivism, Stażewski was also active on the Parisian art scene in collectives such as Cercle et Carré (ca. 1930). In Poland Stażewski was part of Praesens (1926-28) and later the a.r. group (1929-1936), which stood for either “revolutionary artists” or “real avant-garde,” founded by leading Polish avant-garde artists Władysław Strzemiński and Katarzyna Kobro. Among the activities of the a.r. group was the creation of an ambitious International Collection of Modern Art, which could bring the avant-garde to the Polish audience. This collection came to being in the industrial city of Lodz through a collaboration with the local museum, and the first exhibition of works donated from experimental artists across Europe was organized here in 1931 – an event that marked the conception of the Muzeum Sztuki. The Nazi occupation of Poland and the devastating war years put Stażewski’s activities to a halt and also cut the ties between the Polish avant-garde and the Western art centers.

It is here that the exhibition sets in with its chronological display following the multifarious pathways of Stażewski’s career. Among the first cultural manifestations in the new Polish People’s Republic was the large-scale Exhibition of Regained Territories in the city of Wroclaw (previously the German Breslau) in 1948. The exhibition highlighted new industry as Poland’s way into the future and Stażewski, together with fellow artist Bohdan Urbanowitz, designed large panels in glass and other works, which sought to unite the heritage of the pre-war abstraction together with the socialist agenda. The exhibition documents this interesting moment, which carries several themes facing artists in the new republic, including whether the artist should engage in the collective project of building a new culture and should the different arts and crafts collaborate?

The response from the state was the imposition of a doctrine of socialist realism in 1949, which also brought the painters back to their main medium. Stażewski tried to follow this trend with the endorsed motifs of workers and construction, even if in a stylized way drawing on the avant-garde traditions of the pre-war years. Together with other members of the Polish avant-garde, his works were taken off the museum walls in this era and the famed Neo-Plastic Room, created by Władysław Strzemiński in 1948 at the museum in Lodz, was demolished. This model display for the avant-garde museum made the geometrical forms and primary colors stretch over the walls and the ceiling. It was reconstructed in 1960 as a sign of the considerable liberalization after Stalinism in Polish culture, where socialist realism was abolished as a state art already in the mid-1950s. The changing air also made occasional exhibitions abroad possible, as when Galerie Denise René in Paris organized the exhibition Precursors of Abstract Art in Poland in 1957, featuring Stażewski as an important rehabilitation of the pre-war pioneers.

Henryk Stażewski: Late Style, exhibition view, Muzeum Sztuki, Lodz. Photo: Muzeum Sztuki.

In Poland artists like Stażewski experimented with new formats of works and exhibitions. Stażewski developed a type of relief with dynamic, rhythmic elements in bright colors. Meanwhile, experimental exhibition designs in venues such as the Zacheta gallery in Warsaw continued the renewed spirit in Stażewski’s work, which would have been a vital part of the trans-European art scene had the artist had the same opportunities for travel and exchange as his Western colleagues. This interest in spatial forms aligned with the new initiative of the Biennale of Spatial Forms organized by the experimental Polish artists in the small city of Elblag in 1965. Works by Stażewski and other artists were forged at the local metalworks for the exhibition and placed across the city which served as a large outdoor gallery – an example of using available materials for ambitious projects typical of art in socialist Poland. What we encounter in this section of the show suggests that The Biennale of Spatial Forms deserves its own exhibition and should be brought into the history of new exhibition formats as well as history of cultural exchange “across the curtain” as its elements were taken to Denmark for the Danish-Polish sculpture project in 1967: a largely forgotten, but remarkable initiative, where a group of experimental artists from Poland was invited to the city of Aalborg in Jutland to create metal sculptures at the local shipyard to be exhibited around the city, where several of the works still remain.

In the 1960s and 1970s Stażewski, then in his 70s and 80s, took part in the new forms of conceptual art and underground organization. The exhibition shows these network-based activities, and manages to do so in formats available and accessible for presentation, aided by an archive of correspondence and documents in the museum library. At the same time, Stażewski was also present at more official occasions, such as Symposium 70 in Wroclaw, where his colored beams Infinite Vertical Composition lighted the sky in a manner that would become characteristic in art decades later. His color environments, designed to use the psychological effects of color, aligned with the psychedelic impulses of hippie culture and interest in art therapy.(Editors’ note: For further information see Marta Zboralska, “Living Color: Henryk Stażewski’s Interior Models,” Art Journal 80, no. 3 (2021): pp. 38-55)

Henryk Stażewski: Late Style, exhibition view, Muzeum Sztuki, Lodz. Photo: Muzeum Sztuki.

A special chapter in the exhibition is given to the artistic responses to the events in 1981, when Martial Law was declared in response to the Solidarity movement. Stażewski, then 87 years old, continued to participate in the underground events of the unofficial art scene. In the early 1980s these events also included larger initiatives such as the Construction in Progress exhibition in Lodz 1981, where international artists – including Sol LeWitt, Richard Serra and Dan Graham – travelled to Poland to create works together with local workers to support the Solidarity movement.

Late Style provides insight into experimental art in the People’s Republic of Poland through the lens of Stażewski’s tireless artistic production. The exhibition balances well the actual works and documentation of the many different projects and includes a good measure of works by related artists. Some topics covered in the exhibition – such as the 1948 Exhibition of Regained Territories and the Construction in Progress in the 1980s – provide important insights worthy of their own separate examination. The novel biographic approach works well for the exhibition, which is focused and wide-ranging in its presentation. While not decidedly revisionist (there are no radical disclosures about Stażewski in the exhibition) and without a stated agenda, the careful and nuanced examination of Stażewski’s work is a defense of artistic freedom and experimentation in art and life. Lessons can be learned from the experimental achievements under the austere conditions that prevailed during the state socialist regime and the artist’s ability to collaborate and seek new connections. It might not be without its controversies to take up an unconventional artist like Stażewski – and the dedicated monograph beyond the blockbuster is a welcome gesture. How Stażewski continued to experiment and actually found ways of doing so results in a fascinating exhibition – touring this colorful story at museums outside Poland could be a welcoming next step.