In and Out of the Box: Leaps in East/East Dialogues Through the Transnational Activities of Constantin Flondor

A short glance at the East/East dialogues within the timeline of Romanian art of the 1970s and 1980s allows us to identify existing (in)formal cross-border exchanges which foregrounded geopolitical alliances and sporadically connected Romanian artists with like-minded spirits. In the artistic context of the 1970s and 1980s, the state institutions were responsible for foreign cultural agreements and the organization of research trips and touring exhibitions, as well as establishing cultural cooperation with other socialist countries. The assumption that traveling within the Bloc was possible without much difficulty does not always hold true since opportunities were mostly accessible to artists and privileged individuals who were part of the official apparatus (the Romanian Union of Fine Artists or the Committee for Culture and Arts, the Ministry of Culture or the Romanian Institute for Foreign Relations, etc.). They could travel as part of authorized delegations to represent Romania and, occasionally, its participating artists in festivals, biennials or regional conferences. So, despite the celebrated official rhetoric of the so-called socialist communion, contacts within the Bloc were not as permissive as we might imagine; they were monitored and controlled like all international exchanges.

Nevertheless, the East/East dialogues constitute an important chapter of Romanian transnational historiography and should not be underestimated, especially considering the geopolitical aspirations of the Bucharest regime following its response to the invasion of Czechoslovakia.(I am referring to the public speech of the Romanian leader Nicolae Ceaușescu delivered on 21 August 1968 in the Palace Square in Bucharest.) These Eastern exchanges exercised their own part in updating Romanian artists with information about events and tendencies taking place in contemporary art, especially from the Western side.(Through the Union of Fine Artists, it was possible once every two years to order books published in Western countries.) This was possible either via bilateral agreements, exhibitions, and arranged trips (i.e. through the movement of people in the Bloc) or via magazines accessible for individual subscription in Romania (like La Pologne and Projekt from Poland or Form und Zweck from East Germany). Hence, the contextualization of these encounters certainly can clear up the way how certain collaborations became possible among Romanian artists and their fellow socialists. Furthermore, given the fact that in the biography of several Romanian post-war avant-garde artists the connections and intersections with countries such as Poland, Hungary or East Germany are quite substantial, it is relevant to study them closer and understand how they benefited from them in the internationalization of their art.

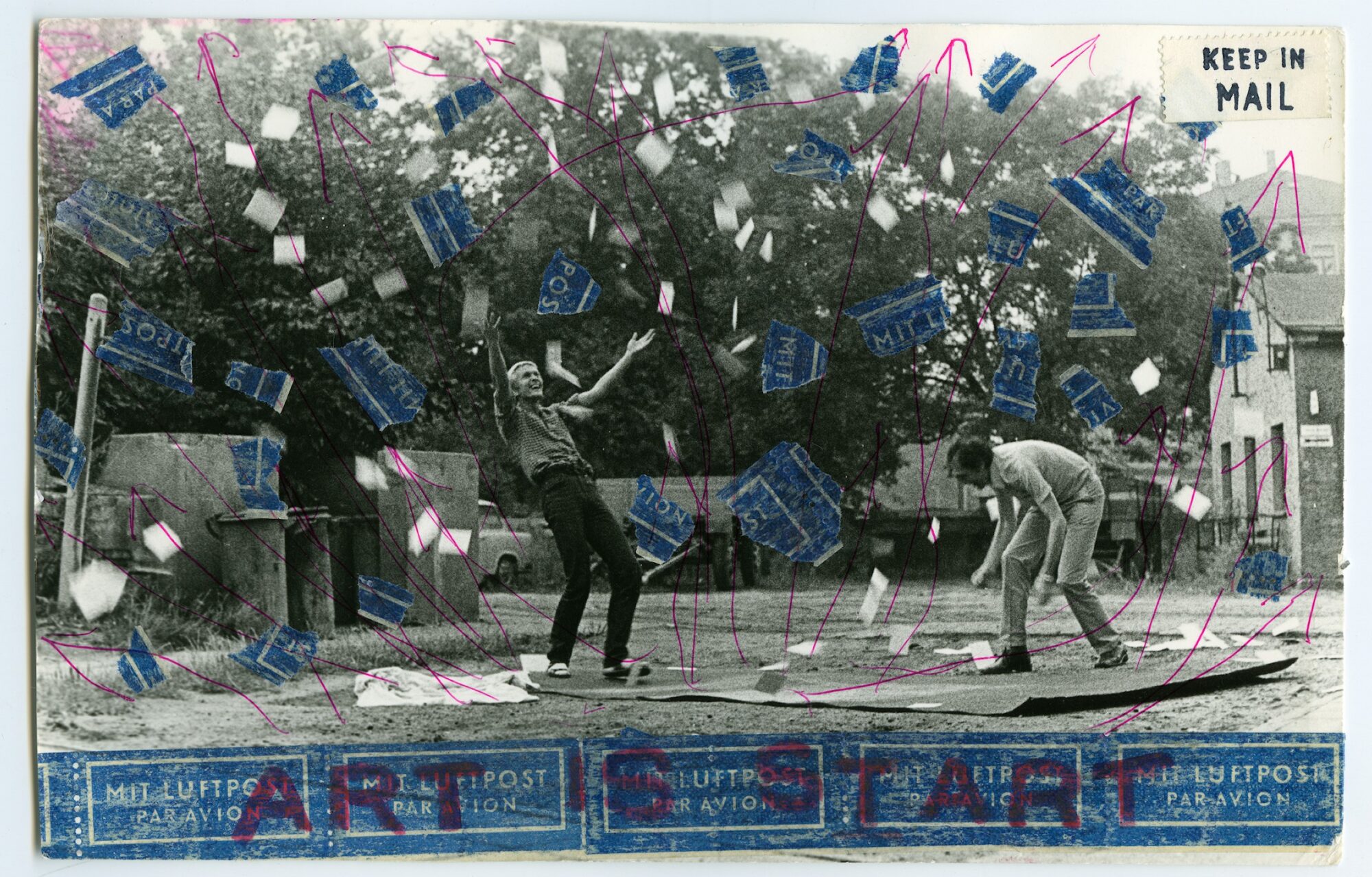

Constantin Flondor with Steffen Giersch, Art Is Start (Between the Sky and the Earth, a Thousand Letters), mail art action, Dresden, 1982. Collage on gelatin silver photograph, colored felt-tip pen. Photographer: Martina Giersch. Courtesy of the artists & Flondor Family Archive.

In what follows, I focus on certain non-hierarchical dialogues carried out in private surroundings and close circles among the Romanian artists and other Eastern European fellows. I investigate how these dialogues determined the participation of Romanian artists in informal international art networks and impacted their lives and/or their process of art-making. This exploration will show that the East/East collaborations were not solely created and regulated by state-administered institutions, but they also came out of a personal longing to renew a connecting space left void as a result of the traumatic pressures exerted by the secluding atmosphere of everyday life during communism. Having this micro-approach in mind, my analysis draws primarily on private archival materials and testimonials to unravel how the transgression of mental and physical borders was possible.

The first part of my text provides an account of travel to and exchanges with the German Democratic Republic (GDR) developed by artist Constantin Flondor, the leading protagonist of Timișoara art groups 111 (1966–1969) and Sigma (1969–1978). I will explore his connections with East German artists, in particular with Robert Rehfeldt (1931–1993), whom Flondor met on the occasion of his first trip to the GDR in 1968. The incidental acquaintance with Rehfeldt prompted his initiation into mail art and in broadening his circle of East German friends. A central figure of the East German and international mail art networks, Rehfeldt was committed to exchanging ideas through art, particularly via his mail art project CONTART(CONTART could be defined as a mail art archive and project, part of which Rehfeldt distributed his yearly CONTART NEWS, a creative and idealistic way to share his beliefs and stay in contact despite distance, thereby overcoming political divides.) (started in the beginning of the 1970s), a playful association of two words “contact” and “art,” which helped maintain a sense of solidarity and togetherness among several artists in the region in times of ideological restrictions and censorship. Flondor shared his mission, as the horizontal, collaborative, and responsive dimension of mail art resonated with the participatory and dialogic nature of the art groups he co-founded (111, Sigma, and Prolog). It was Sigma’s experimental pedagogical program, put into practice at the Timișoara Arts Lyceum and based on Bauhaus educational ideas, that triggered the second trip of Flondor to East Germany in 1972. As a consequence of the contacts enabled by the state-organized trips, Flondor was encouraged to travel privately in 1979/1980 and 1982 at the invitation of his East German friends and to continue the dialogue with them via post.

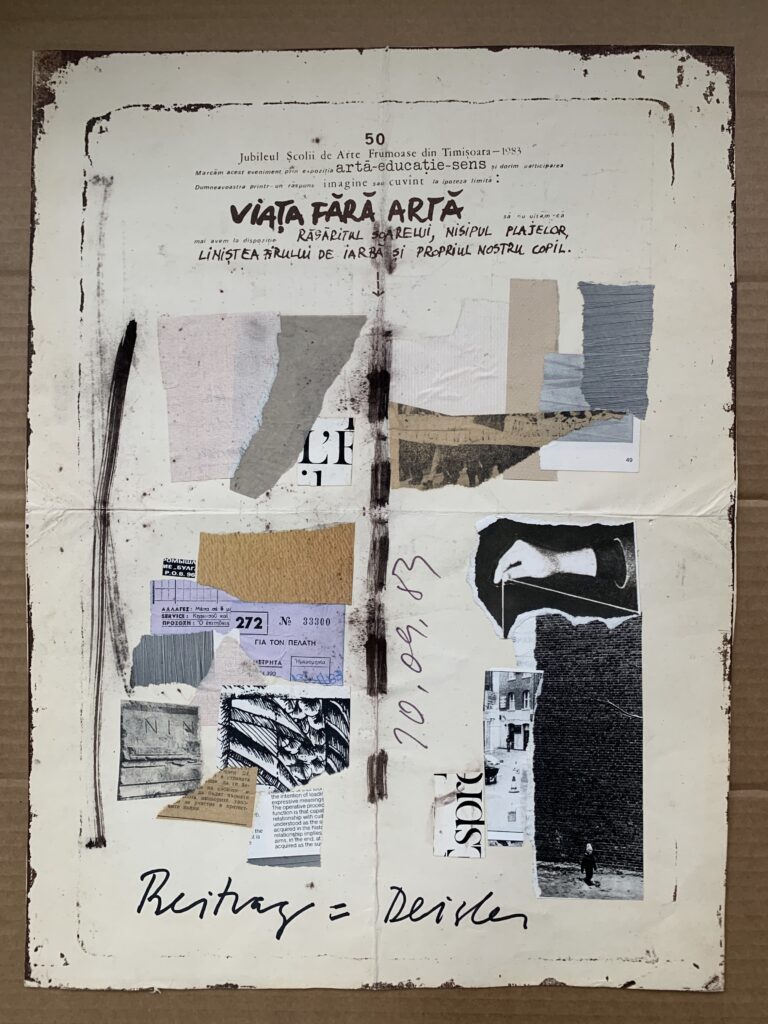

In the second part of this text, I briefly examine the landmark mail art project Life Without Art (1983) initiated by Flondor in collaboration with his Sigma colleague, Doru Tulcan, and their former student at the Timișoara Arts Lyceum, artist Iosif Király. Although mail art did not play a significant part in Flondor’s artistic practice, it did expand his interests and allowed him to be part of an international artistic community. This community was driven by common questions, the search for freedom of speech using a lingua franca to communicate abroad, and various means of experimentation, dissemination and encryption of messages that aspired to reimagine the limits of art.(“Mail art is not a cheap means to produce and disseminate art. The essential aspect is its subtlety, its power to quickly send messages out into the world which are more or less encrypted. In a country where typewriters are registered and examined annually by the militia, where the manufacture of a stamp was subject to censorship and required permission from the special authorities, few artists had the courage to express themselves. We were hungry for contacts, communication, and sometimes frivolously ignored all risks.” Constantin Flondor, “Letter to Mail Art,” in Alina Șerban, ed., When Eye Touches Cloud (Bucharest: P+4 Publications, 2021), p. 443, originally published in Mail Art: Osteuropa im internationelen Netzwerk (Schwerin: Staatliches Museum Schwerin, 1996), pp. 79–83.) The international section of the above-mentioned project relied on the contacts received by Flondor from Rehfeldt as a consequence of the consolidation of their friendship.

Four Trips to Germany

In 1968, two months after the invasion of Czechoslovakia, a bus trip was organized by the Romanian Union of Fine Artists to East Germany via Prague. The moment was not incidental since, after Ceaușescu’s refusal to participate in the Soviet invasion of Czechoslovakia, an acceleration of foreign exchanges and cooperation began to be felt. These were the few promising years in Romanian society when everything seemed possible. As a result, an increasing number of individual or group trips were organized as part of the bilateral cooperation established between the national Unions of Fine Artists in the region.(In May 1972 a treaty of friendship, collaboration, and mutual assistance between the Socialist Republic of Romania and the German Democratic Republic was signed in Bucharest.) This time the Bucharest headquarters of the Union advertised the trip to East Germany across the country and local Unions proposed lists with participating artists, among them Flondor.

Born in Czernowitz (today Ukraine) in 1936, Flondor left his hometown as a refugee in 1944, and his family settled in Timișoara, a city in the western part of Romania. Between 1964 and 1965 together with his colleagues from the Timișoara Art Lyceum, Karola Fritz and Ștefan Bertalan, Flondor began to study and translate several texts from German including Paul Klee’s Pädagogisches Skizzenbuch (Pedagogical Sketchbook) and his Das bildnerische Denken (The Thinking Eye), as well as Johannes Itten’s Kunst der Farbe (The Art of Color). These were important sources in the conceptualization of the artistic and pedagogical program of the later Sigma Group, so the focus on the Bauhaus pedagogy and its community of artists was of interest. Familiar with the German language, which he learned at home, Flondor signed up for the Union’s trip to East Germany alongside other colleagues from Timișoara like Paul Neagu. The artist recalls his hope to see works that he only knew from printed sources.

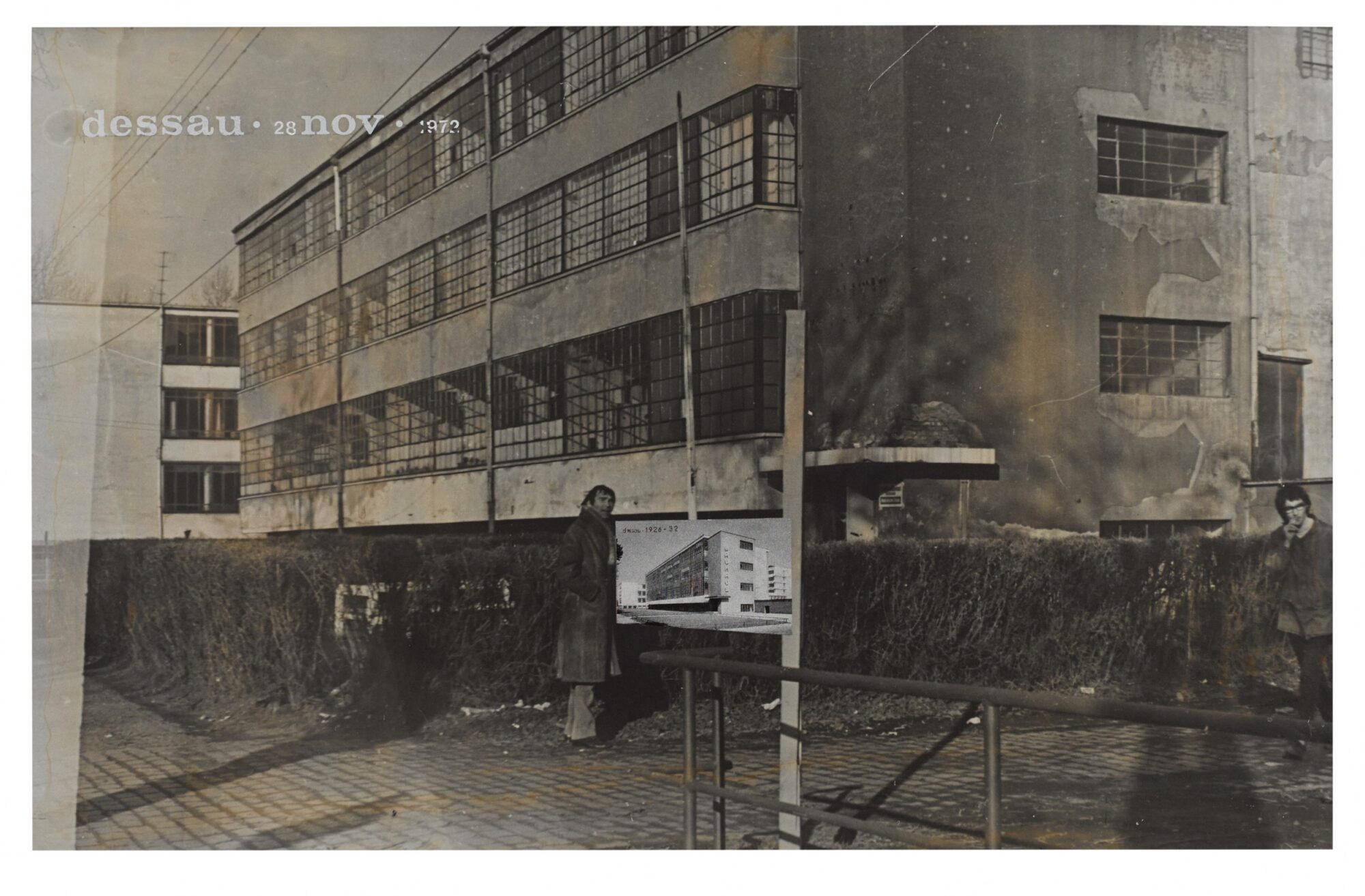

Constantin Flondor in front of the Bauhaus building in Dessau, 1972. Collage on gelatin silver photograph, montage on plywood. Courtesy of the Flondor Family Archive.

Although the trip followed a strict itinerary, in Berlin it was possible to take a day off from the official program. Flondor visited the headquarters of the GDR Union of Fine Artists in Berlin requesting contacts of contemporary artists with whom he could meet. He obtained two meetings, one with Rehfeldt, the other with Hanfried Schulz (1922–2005). In the climate of changes opened up by the public discourse of Ceaușescu against the Soviet repression in Czechoslovakia, any door seemed to be open for Romanians, as the artist remembers. Therefore, the enthusiastic encounters with the East German artists evinced common worldviews, and aesthetic interests, and moreover allowed individual affinities to become the pillar of lifelong friendships. Flondor described his first encounter with Rehfeldt: “A telephone call to Pankow. Meeting in a café, and later in his studio. Straight talk and the beginning of a friendship of more than twenty-five years. A long-term correspondence aroused my subsidiary interest in mail art,”(Constantin Flondor, “Letter to Mail Art,” p. 443.) a practice that was in line with the experiments he carried out in film, photography, and land art.

In 1972 Flondor had the chance for a second trip to East Germany, this time supported by the Council of Socialist Culture and Education, an institution directly attached to the Central Committee of the Communist Party in charge of cultural and educational policies. One of its tasks was to facilitate contacts between socialist countries and to ensure access to the latest novelties in various fields. Likely due to the successful implementation of the experimental pedagogical program at the Timișoara Art Lyceum, where he was director, Flondor had the opportunity to be part of the documentation and specialization program and to draft his own itinerary in East Germany. The artist was not permitted to travel alone, even though he spoke German well, a translator accompanied him, most probably to report on his meetings. Following the paths of the Bauhaus School, he visited Berlin, Chemnitz, Erfurt, Weimar, Wernigerode, Halle, and Dessau from October 16 to December 5, 1972. The 1972 trip to East Germany was recorded in the artist’s diary and documented on Super 8 film and slides. For example, he documented his meeting in Chemnitz with Marianne Brandt, a former student of Moholy-Nagy, who gave him a tour of the exhibition dedicated to Bauhaus School in the city museum.

Flondor was already in correspondence with Rehfeldt, and informed him ahead of his trip and arrival in Berlin via letter.(Rehfeldt replied in a letter dated August 28, 1972: “Viv l’art constructiv” as a reminder of Flondor’s participation in the 1969 Nuremberg Biennale, Konstruktive Kunst: Elemente und Prinzipien. He expected Flondor’s stay in Berlin to be longer so he could study new materials. Rehfeldt informed Flondor that Polish artists were also there for a similar visit.) In Berlin, Flondor participated in one of Rehfeldt’s evening studio meetings, sharing information on the Timișoara experimental pedagogical program on slides and films. On this occasion, he met artist Joseph Huber (1951–2002), who later mentioned Flondor’s presentation as a source of his orientation towards optical effects in graphics. On 4 December 1972, a similar talk about the Art Lyceum pedagogical program took place at the Form + Zweck magazine to which Flondor already had a subscription in Romania. The following year, an article about the Timișoara Art Lyceum was published in the magazine.(Rehfeldt arranged a meeting for Flondor with a journalist of the magazine, Form + Zweck, then in the 1973/3 issue of the magazine three short texts on the art education in Poland, USSR, Romania, and Hungary were published. “Oberschüler gestalten,” Form + Zweck, no. 3 (1973): pp. 25–26. https://digital.slub-dresden.de/werkansicht/dlf/131250/28)

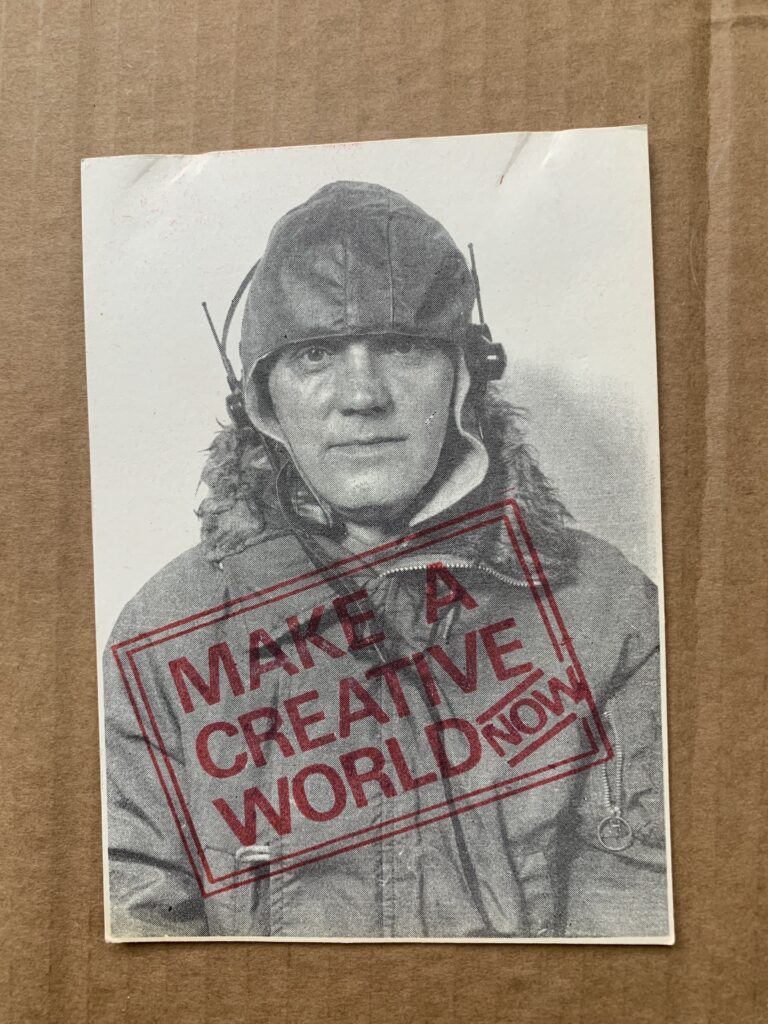

From the mail art correspondence with Robert Rehfeldt, 1976. Black and white gelatin silver photograph, stamp. Courtesy of the artists & Flondor Family Archive.

Rehfeldt’s studio sheltered a huge archive of mail art correspondence, and through him, Flondor established in-person meetings and/or postal contact with other East German artists.(Flondor was in contact with the active members of Dresden mail art circle Martina and Steffen Giersch, Birgen Jesch, Irene Wache, Jürgen Gottschalk, Erfurt art restorer Rainer Luck, Berlin artists Ruth-Wolf Rehfeldt, Karla Sachse, Friedrich Winnes, Joseph Huber, Oskar Manigk, Erhard Monden, Volker Kraft, Eckhard Koenig, Detlef Kappis, Jürgen Schweinebraden, Magdeburg artists Anette and Michael Groschopp, Joachim Bartels, or Frankfurt artist Henning Mittendorf. Other artists with whom he was in contact were Jens Barkschat (Altenburg), Terra Candella (Ohio), Guillermo Deisler (Plovdiv), Klaus Groh (Edewecht), Jürgen Kierspel (Stuttgart), Clemente Padin (Montevideo), Piotr Rypson (Warsaw), Thomas Schultz (Ladek Zdroj), Giovani StraDA DA (Ravenna). I kept the original locations from where these artists corresponded at that time with Flondor as retained in his archive.) The concept of postal mail as art proposed by Rehfeldt(See: Robert Rehfeldt, “Make a Creative World Now,” available at https://artpool.hu/MailArt/chrono/1984/pdf/Rehfeldt.pdf, originally published in Correspondence Art: Source Book for the Network of International Postal Art Activity, edited by Michael Crane and Mary Stofflet (San Francisco: Contemporary Art Press, 1984), p. 273.) came out of a real urgency to break borders, escape isolation, and restore a common sense of camaraderie and hope. Mail art provided a way to experience such a subversive collective shared practice. Mutual learning about each other’s art preoccupations, life, and context, constituted in fact the basis for advancing a new social paradigm. Within it, the spiritual, humorous, and nonconformist messages distributed around the Eastern Bloc via mail challenged the repressive political apparatus and dislocated the terms under which art was read. “Artists of all countries unite,” “Art in contact it’s life in art,” “Your ideas help other ideas in art,” “Please don’t think about me now,” “Artists come and go, art remains,” “Art Today is limitless,” “Art today is the story of tomorrow,” and “This card shares my thoughts with you,” were a few of the statements sent by Rehfeldt into the world on postcards, posters, photographs, etc. They accommodate the struggles of communicating beyond borders, beyond ideologies.

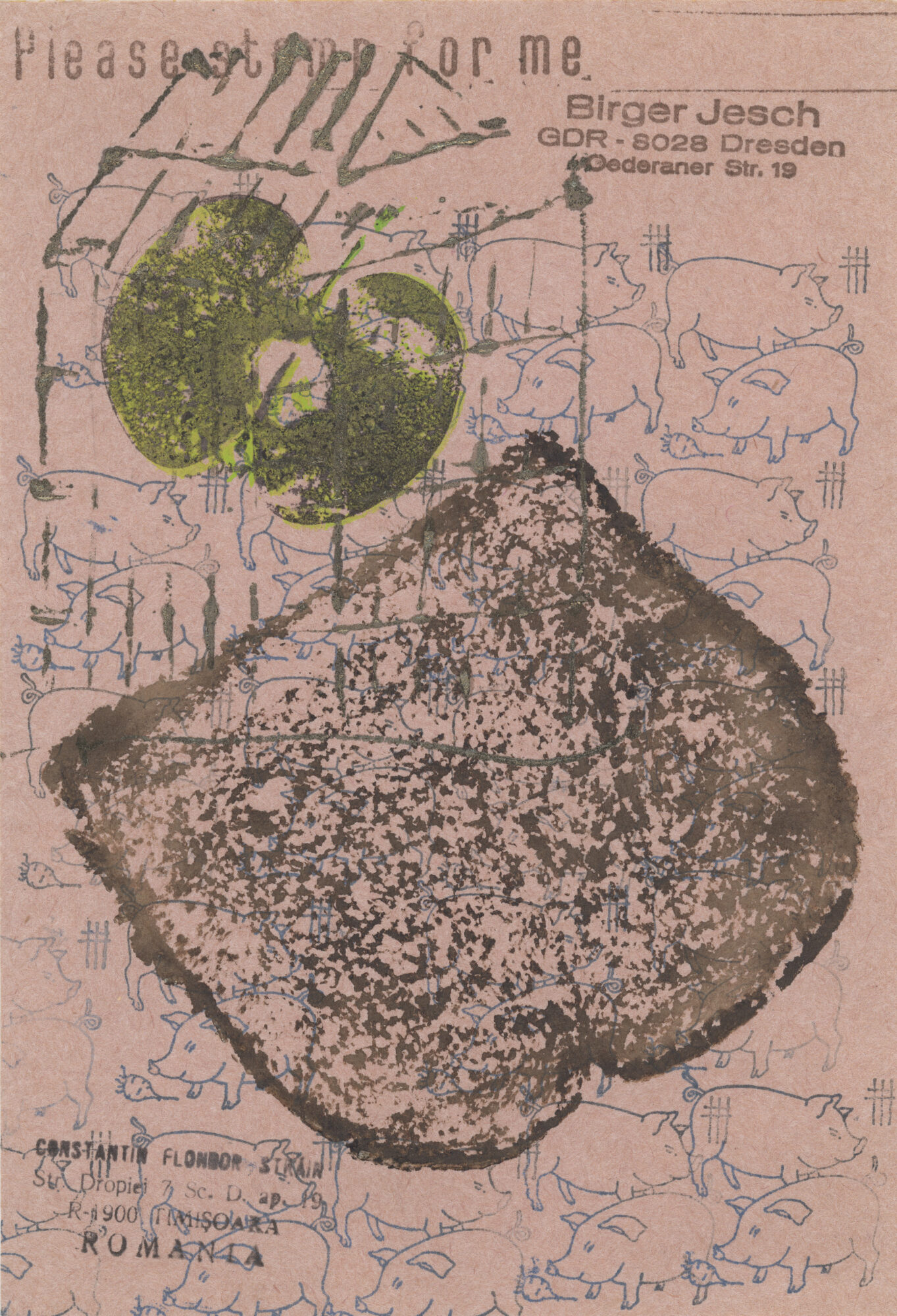

Flondor was the Romanian contributor in Rehfeldt’s CONTART network. His name was included in the first issue of CONTART NEWS published in 1977 by Rehfeldt in the format of a poster, subtitled “Artworkers News. Artists of All Countries Unite,” echoing Karl Marx’s slogan, and which Rehfeldt usually sent on the occasion of the New Year’s wishes. The messages sent by Flondor through mail reflected his everyday reality. For Birger Jesch’s project, Rubber Stamps from Europa (1982–1983) Flondor sent stamp images of a potato, bread, and apple slices and a knotted string—all symbolic parameters of his daily life. Nevertheless, as the documents evidence, Flondor’s participation in mail art is indebted mostly to his East German connections, which were more than art contacts. Flondor forged friendships and engaged in dialogues that were not ephemeral, they continued even after the fall of the Wall. What he found within this circle of artists was a lively, friendly, and very active atmosphere, something which he missed in his own country. Their mail network incited him to solidarity and to venture to bypass the constraints of the political system.(Personal interview conducted with Constantin Flondor via e-mail on May 2, 2022. Rehfeldt’s letters were sent from Berlin and other places he traveled to. He informed Flondor about the artists he met, articles he read, or exhibitions he took part in, sending him further addresses to contact.)

Part of Flondor’s submission for Birger Jesch’s project Rubber Stamps from Europa: Please Stamp for Me, 1983. Several stamped images on colored paper. Courtesy of the artists & Flondor Family Archive.

Further trips in the winter of 1979/1980 and the summer of 1982 to East Germany were organized privately by Flondor. According to the travel regulations in Romania, it was possible to travel to a socialist country once every two years, and upon return your passport had to be handed over in twenty-four hours. The first journey was made by train with his wife, Sanda and daughter Andreea, and the Sigma colleague Doru Tulcan and his wife, Mimi to celebrate Christmas and New Year’s Eve together with Rehfeldt’s family. The itinerary was Berlin, Dresden, Erfurt, and Weimar, stopping at his East German friends. The artist took his Super 8 mm camera and filmed a spontaneous action together with Rehfeldt in his Berlin studio, the footage being preserved in a raw version. One can see Rehfeldt wearing a military helmet while Flondor has a worker helmet, zooming in and out the cover of the Russian art magazine Iskusstvo (Art), representing Fyodor Reshetnikov’s famous 1948 painting of Stalin in his cabinet. Next, we see Rehfeldt as Flondor is covering him with a transparent plastic sack, pretending to freely smoke a cigar, miming with his hand gestures of an ordinary conversation, and later we see him in the mirror onto which he sprays the word CONTART. The last sequence of the film spots the word Grenzgebiet (frontier zone), an ambiguous word which refers to one of his statements disseminated via mail art: KUNST HEUTE IST GRENZENLOS (art today is limitless).

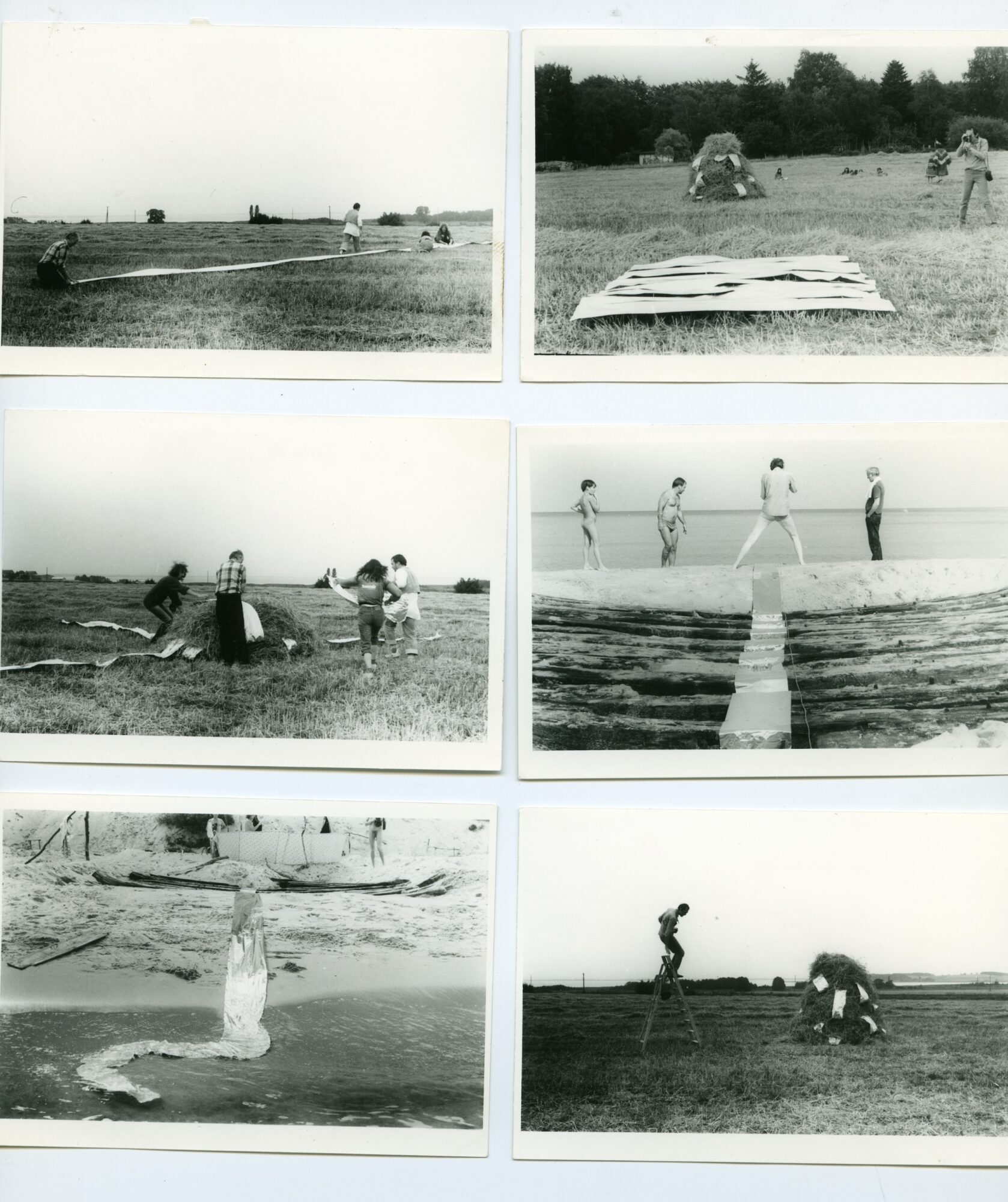

La Folie d’Ückeritz, 1982. Flondor’s action in collaboration with Oskar Manigk, Rainer Luck, and Erhardt Monden,

Usedom Island, Ückeritz. Six gelatin silver photographs. Photograph by Rainer Luck. Courtesy of the artists & Flondor Family Archive.

The summer of 1982 was once more under the sign of East German friendship, this time in Ückeritz (on the island of Usedom), in the holiday house of Oskar Manigk, following an invitation received from Rainer Luck. Alongside Manigk and Luck families, Erhard Monden and his wife were present. The land art action La folie d’Ückeritz employing aluminum foil, sand, haystack, enacted an open and collective form of experimentation, contesting the rigid hierarchies of genres and aesthetics. The roll of aluminum foil, which was brought by Luck for the actions, gave a starting point for a series of open-air interventions, some being recorded on Super 8 mm film and some photographed. Manigk created a joint between the beach and a shipwreck using the foil, Luck placed the foil on the stubble, Monden arranged the foil at the border of the sea and shore and placed himself naked half in the water half on land for approx. twenty minutes, while Flondor’s action consisted of folding wheat and the foil in the shape of a cross. He sliced a ten-leu Romanian bill and symbolically combined its reverse side with kernels of wheat on a blank sheet of thick paper. The back face of the 10-leu bill represented sowing machines harvesting wheat, suggesting the success of the agriculture industry in Romania during the communist rule. The gesture of the artist is a critical comment on the harsh years of recession and food shortage which dramatically affected day-to-day life during the 1980s in Romania. One year later, in 1983, Flondor created one of his best contextual films, a critique of the rationing of food during Ceaușescu, called Ani-vărsare. The title is comprised of two words: ani (coming from anniversary, as it was filmed on the occasion of Ceaușescu’s 65th birthday) and vărsare (coming from the verb a vărsa, meaning “to spill,” “to puke” or “to vomit”).(More on Constantin Flondor’s experimental films, see: Katarzyna Cytlak, “ Sketches for a Visual Consciousness. Constantin Flondor’s Experimental Films (1972–1985),” in Șerban, ed., When Eye Touches Cloud, pp. 286–306.)

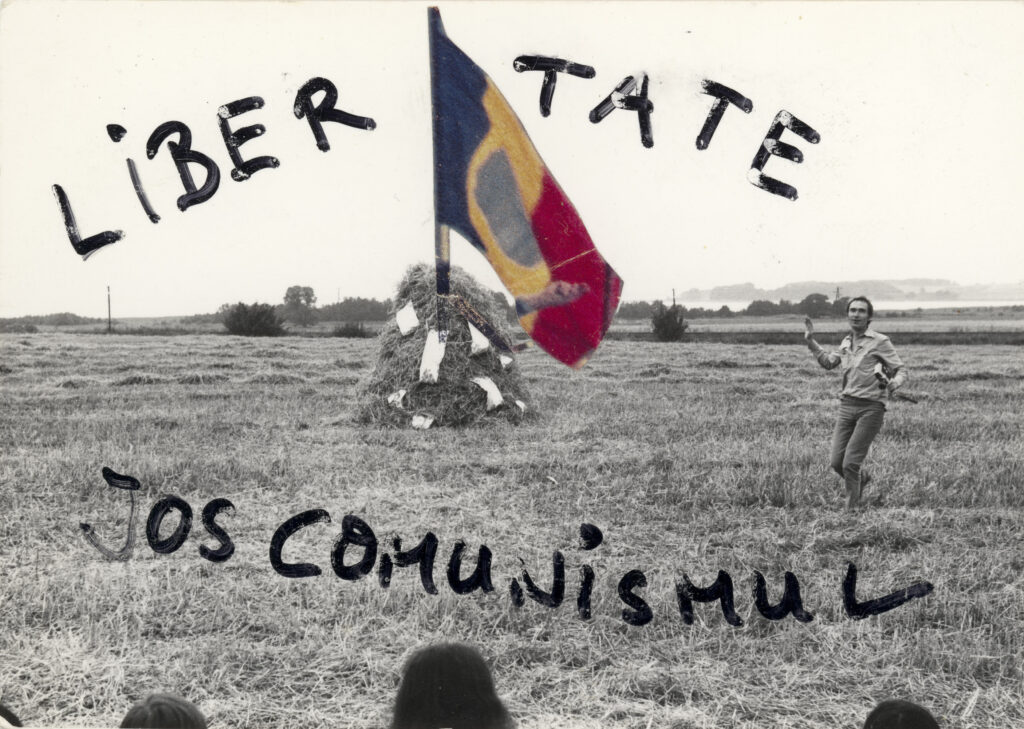

During his return journey, Flondor visited Steffen Giersch in Dresden. The action ART IS START: Between the Sky and the Earth, a Thousand Letters took place in the courtyard of Giersch’s house. Flondor and Giersch threw hundreds of letters into the sky, which was documented in photos and sent to Flondor later via mail. As an expression of conviviality, the photo-documentation of their various collective or solo actions was subsequently retouched using various graphic and montage techniques and circulated in their correspondences.(Some of these documentations reappeared on the eve of 1989 events, for example, Luck circulated a photograph taken of Flondor next to a haystack in Ückeritz, overwritten in Romanian: “Libertate—Jos comunismul” (Liberty—Down with Communism).)

From the mail art correspondence with Rainer Luck, 1989. Collage on gelatin silver photograph, colored flag, felt-tip pen. Courtesy of the artists & Flondor Family Archive.

In 1984, Flondor’s last trip to East Germany took place. He was invited by artist Michael Grohschopp to participate in the Magdeburg-Stadt-pleinair, where other artists from socialist countries were present (from Poland, Finland, Czechoslovakia, Estonia, and Lithuania).(It is important to mention that some of Flondor’s East German friends also visited Timișoara during the 1980s: the son of Robert Rehfeldt, René, Friedrich Winnes, Rainer Luck with his wife and children, Steffen Giersch and Michael Grohschopp.) This time the artist received his passport with difficulty, because of his work Confession, a self-portrait onto which a religious Bogomil text was written and was shown in the group exhibition IDEEA in Timișoara. Belief and faith were hardly accommodated by the authorities, and any allusions to spiritual and religious practices were considered suspicious and consequently against the regime, especially in the1980s, the sternest period of Romania’s socialism. Many intellectuals were attracted to belief (in the sense of orthodox spirituality or other movements such as Transcendental Meditation),(A new spiritual movement founded by India-born Maharishi Mahesh Yogi and brought to Romania by engineer Nicolae Stoian attracted a considerable number of intellectuals, but later was banned and participants felt under political repression.) which constituted a form of escapism from the restraints of the public sphere.

Life Without Art?

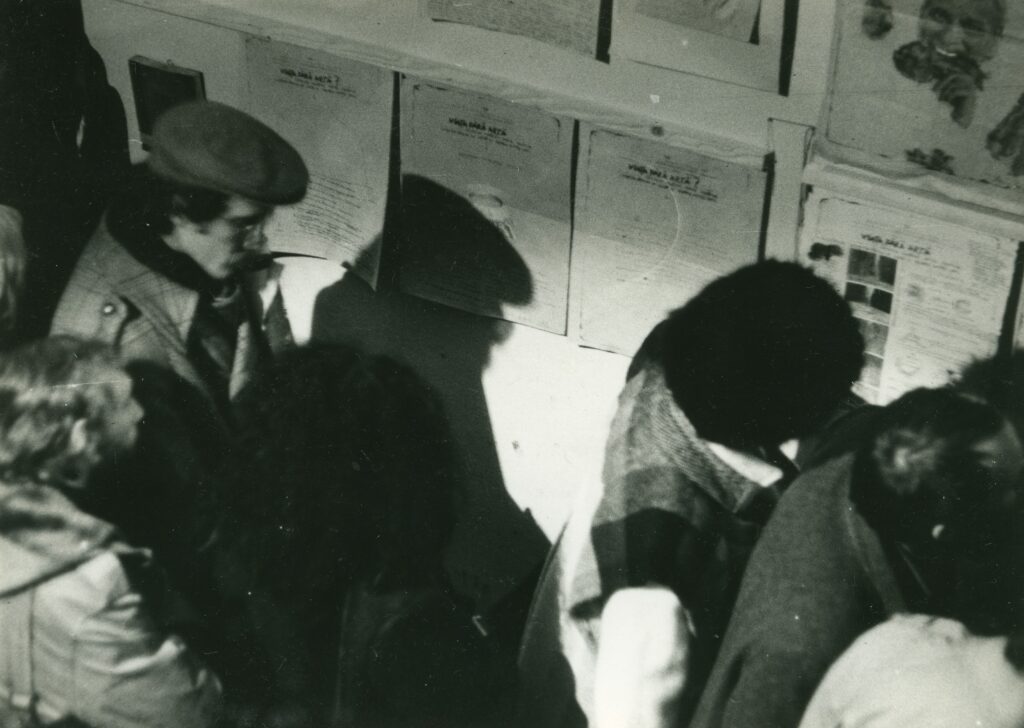

In March 1984, the first Romanian mail art exhibition opened in Timișoara, in Flondor’s studio.(The second exhibition on the topic was Artă poștală / Mail Art (December 1985–January 1986), organized by Mircea Florian, Dan Mihălțianu, Andrei Oișteanu under the aegis of Atelier 35 in Bucharest. It was the largest national presentation of mail art with more than one hundred participants from all over the country (including not only artists).) The semi-private event was the outcome of a questionnaire launched in 1983 by the artist in collaboration with the Sigma member, Doru Tulcan, and their former student at the Timișoara Arts Lyceum, Iosif Király. They multiplied and distributed an A3 questionnaire via mail to various addresses in Romania, Bulgaria, East Germany, West Germany, Poland, and US.(Although the survey was sent to all addresses on Flondor’ list, including Robert Rehfeldt, it is possible that some did not reach the addressees or the answers were never received in time, most probably, to the interference of postal control especially in the case of international correspondence.) The recipients were requested to reply to “the radical hypothesis”: Life Without Art?, with “image or word.” A quasi-poetic text Let Us Not Forget That We Still Have the Sunrise, the Sand of the Beaches, the Quietness of the Grass Blade, and Our Own Child was added as a subtitle. The short and bold inquiry aimed to confront the austere, regressive, and repressive atmosphere of the cultural and educational life in Romania during the 1980s, being provocative (how our life could be without art), and rhetorical (claiming that art cannot be evicted totally from the social space). The political register of their initiative aimed at opening a discussion on the place of art in society, especially under the dystopian conditions that dictated Romanian artistic life during the 1980s.(For instance, the difficulty of younger artists to get studios or become members of the Union of Fine Artists.)

Life Without Art?, mail art exhibition opening in Constantin Flondor’s studio, Timișoara, 1984. Photograph by Iosif Király. Courtesy of the artists & Flondor Family Archive.

The release of the survey took place on the occasion of the fifty-year jubilee of the establishment in 1933 of the Timișoara Art Lyceum, which consisted of a series of public events (exhibition and symposium). Several guests, artists, and art critics from Romania’s main cities (Bucharest, Timișoara, Cluj), representatives of the Bucharest Union of Fine Artists, and teachers from other educational centers participated in the anniversary events. Flondor proposed to include the received answers to the questionnaire in the exhibition organized on this occasion at the Bastion Art Galleries in Timișoara. The official rejection of this proposal as part of the anniversary event led to the artist’s spontaneous decision to host the exhibition in his studio. The exhibition collected mostly the answers received from local and domestic contributors (writers, musicians, art critics, and artists), however, not all of the materials included had been posted as some of the participants were unfamiliar with mail art and had brought their pieces directly to the space, while others sent a package to one of the three artist-organizers. The mounting of the exhibition in Flondor’s studio was unplanned, adding retrospectively a subversive dimension to the project since his studio resided in the same building as the headquarters of the Timișoara Union of Fine Artists, where the anniversary symposium took place. All the guests had access to the exhibition, they could read the submissions carefully, some reacting directly, some preferring a tacit response. There was no official mention of the exhibition, neither in the press nor in the symposium. The lack of recognition of the action initiated by the three artists had two immediate consequences. The first was that in April 1984 the exhibition traveled to the small city of Lugoj, to Galeria Pro Arte, at the invitation of Silviu Oravițan, the head of the Lugoj Union of Fine Artists, who also responded to the survey. It was possible because censorship was lighter in peripheral contexts than in the big cities. The second consequence revealed the clear delineation of boundaries between ideological borders and artistic autonomy: after the opening in Timișoara, an informative surveillance file was opened on Flondor, containing data collected from his colleagues, letters, and intercepted phone calls from September 1984 until 1989.

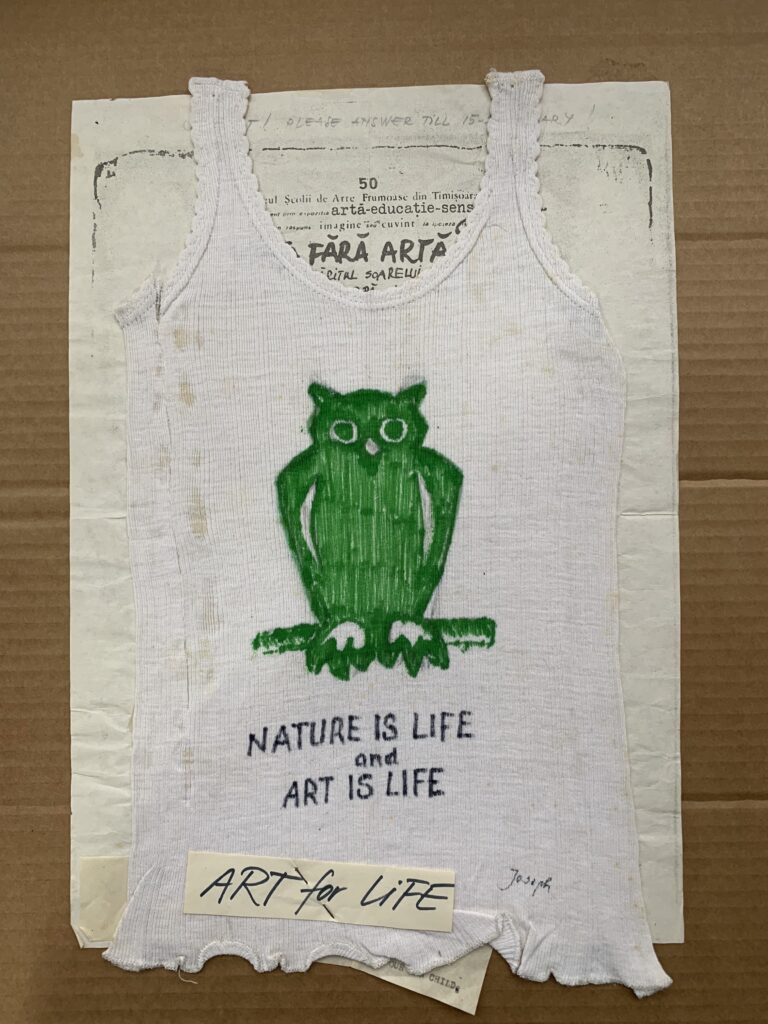

Joseph Huber’s contribution to the Life Without Art? project initiated by Constantin Flondor, Doru Tulcan, Iosif Király, 1983. Courtesy of the artists & Flondor Family Archive.

Guillermo Deisler’s contribution to the Life Without Art? project initiated by Constantin Flondor, Doru Tulcan, Iosif Király, 1983. Courtesy of the artists & Flondor Family Archive.

The project was informed by and modeled on the practice of exchange experienced via Rehfeldt’s circle of friends. However, only a few international corresponding participants—Guillermo Deisler, Michael Groschopp, Joseph Huber, Tomasz Schultz, Siegfried Otto, Aloys Ohlmann, and Hanning Mittendorf—sent their reflections on the questionnaire. Retrospectively it can be stated that the exhibition’s theme revolved around a universal human need—to appreciate art as a means of educating and touching individuals, something resonating with Rehfeldt’s concerns of humanizing the everyday through the rapid dissemination of ideas through art.(More on Rehfeldt’s art and postal projects see: Robert Rehfeldt. Denken Sie Jetzt Bitte Nich an Mich (Berlin: Gallery ChertLüdde, 2021).) The exhibition highlighted the non-hierarchical and non-exclusive character of mail art, all messages being accepted and included, as well as their heterogeneous aesthetics. Flondor was familiarized with the international calls for different mail art shows and with the chain letters which introduced specific themes, formats or rules to produce and spread the information further. This model of networking was a form of contact, enacted via artistic gestures and extended on and off with the help of translocal networks. As one message from Jürgen Kierspel reads: “Live through communication. Mail art has no limits…”

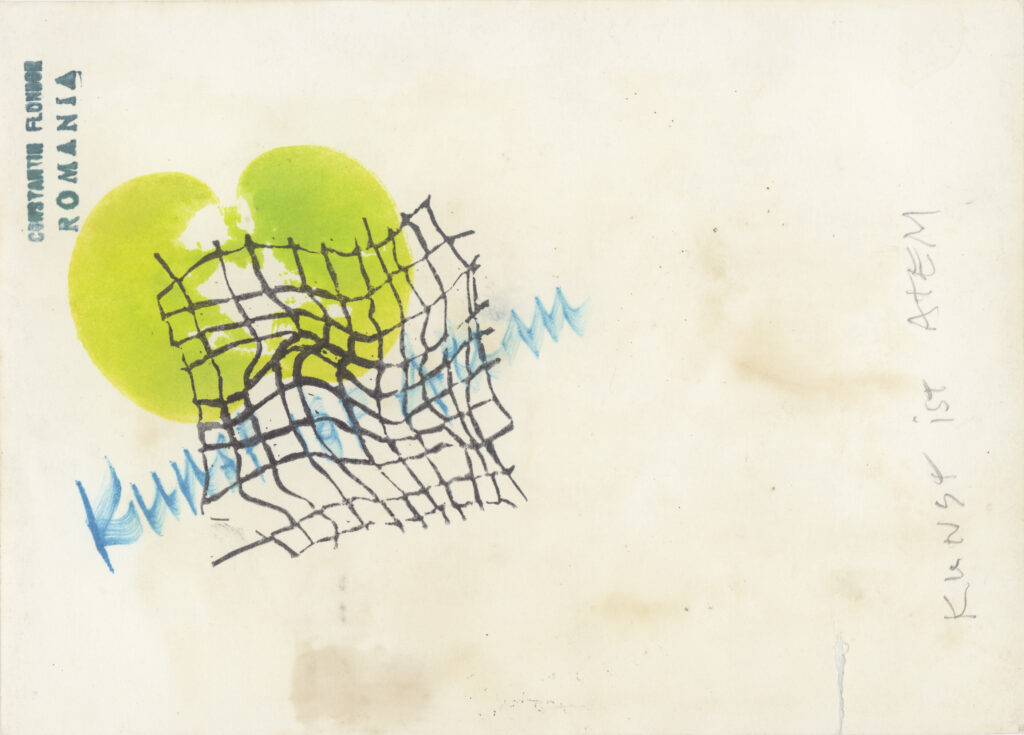

What was at stake during this specific event was a rationale put in effect by mail art principles: to overcome political obstacles through communication, to see oneself as being part of a collective body, exercising how to learn to think together.(Interestingly, the magazine, Atelier 35 Timișoara, editors Călin Beloescu and Pavel Vereș, printed under the aegis of the Timișoara branch of the Romanian Union of Fine Artists included in 1986 an extensive synthesis of mail art (m.a.) signed as Atelier 35: “m.a. was a collective oeuvre; the real sense of m.a. was live communication; the m.a. cannot save art or life, it is what it is and nothing more; m.a. opens a socio-cultural space to conceptualize and operate in a synthetic direction, etc.” The issue was not numbered and not dated.) So, it was precisely this sense of communion, the poetic-philosophical understandings of the world and the critical scrutiny of reality that mattered to Flondor. For him, KUNST IST ATEM (Art is breathing), as he states in one of his mail art exchanges. In Romanian language ARTA ESTE DUH, the word duh has a double meaning: “soul/spirit” and “appearance.”

Constantin Flondor. Kunst in Atem / Art in Breath, 1983. Stamp on paper, felt-tip pen. Courtesy of the Flondor Family Archive.

The documents preserved in Flondor’s archive emphasize the importance of his East German connections. Undertaking a close reading of the materials shows us a more nuanced representation of a world interconnected at all levels, drawing important bridges between official history and private history, counterbalancing the flow of information available from official sources with the artist’s existing records. Guiding the attention towards protagonists and agents, and their stories, one can discover leftover accounts, pieces from a puzzle which is not always, as hoped, that of a grand narrative. The corpus of materials, some overlooked, some neglected by the artist himself, actually underscores and fills existing gaps in his biography, clarifies incomplete data, and suggests a more complex and changing picture of the local landscape placed in juxtaposition with the regional one. It allows us to understand the source of certain gestures and conceptual connections between events that may appear to be unrelated.

A closer examination of such in-between spaces connecting personal biographies and national narratives clarifies the social nature and main purpose of these transnational interactions: to establish dialogues, overcoming the immediate ideological and bureaucratic obstacles, thus renewing the symbolic and epistemic dimension of communication. The kind of dialogues enforced, most often privately, among people, (para)-institutions, and localities, through person-to-person contact or at a distance, allow us to retrace today less known historical connections, to reconfigure the then impenetrable social circles of art and to make accessible factual, contextual and theoretical associations which inform us about the not-yet-acknowledged stories of the art and artists in the region. These interpersonal or officially framed interstices and the significantly different histories that can be retrieved from them are intimately linked with the fascinating traveling trajectories in a world which was not as homogenized and polarized as it was deemed by the political leadership. In turn, the establishment of contacts within the socialist Bloc emphasizes the complex and labyrinthic mechanisms of transactions between the state, its governing institutions, and the artist. Moreover, the delineated porous zones that appear inevitable in a centralized system prove that not everything can be controlled and kept in isolation and that sometimes the differences between the administrative apparatuses of socialist countries generated opportunities to be taken.(Flondor underlines that the East German system was more permissive in the 1980s as stamps were available in commerce and typewriters were not checked annually by the secret police.) Therefore, it is perhaps not accidental to say that the insistence in recent studies on the manifold interrelations and entanglements induced by scarce or long-standing flows of transnational artistic exchange reminds us that writing the history of art is not a stagnant operation, it is constantly shaped and reshaped by new (re)sources and, as a result, permanently updated.

This article would not have been possible without the constant support and dialogue with Sanda and Constantin Flondor starting in 2015. The visual materials selected are from Flondor’s personal archive. Acknowledgements: Jecza Gallery (archival support & photography), Institute of the Present (documentation).

This article is part of a Special Issue on Regional Resonances. You can read other articles from this Special Issue published on ARTMargins Online below: