How Do Bodies Resist? Image and Self at Museum Ludwig

Image/ Counterimage at Museum Ludwig Cologne, April 22 – August 27, 2023

Drawing on their excellent photographic collection, Cologne’s Museum Ludwig has dedicated an exhibition to the photographic self-portrait. The show, titled Image/ Counterimage, brings together several key works by the artists Carrie Mae Weems, VALIE EXPORT, Ana Mendieta, Sanja Iveković, and Tarrah Krajnak. Spanning three rooms, it offers an engaging tour of different artistic strategies of staging the female body as a site of resistance. While the former four artists represent established positions regarding photography in the feminist context since the 1970s, the latter introduces a more recent inquisition of the body and its ambivalent role as a model, muse, and mirror. Krajnak’s piece constitutes one of the museum’s most recent acquisitions, here on show for the first time. Opening the exhibition, her work figures as the curatorial linchpin, tied to a previous generation of female practitioners and serving as a point of departure for revisiting the rich legacy of art’s feminist revolution. Accordingly, the show not only gives rise to questions surrounding the continued relevance of post-war feminism but also to the question of how today’s museums choose to expand their collections and the controversial implications connected to such decisions.

Notably, this is not a show of the iconic singular photograph, but rather the serialized one. All exhibited works consist of multiple images, which are arranged in mostly horizontal sequences, rhythmically threading through the different rooms. Highlighting the serial underscores not only the temporal dimension of the photographic process, but also the photograph’s role of documenting the physical performances underpinning them. In this regard, the display points to a core aspect of the works, namely the tension between bodily presence and its representation. The notion of our bodies being suspended between image and physical reality became increasingly influential during the decades in which the exhibited artists worked and, in turn, found different articulations in their respective pieces as a tool for inquiry and critique. Furthermore, seriality connects to the idea of the body and the gendered identity inhabiting it being subjected to a continuous process of construction and transformation. These dynamics indicate an instability of the body, containing both potentiality and threat, which takes center stage in this exhibition.

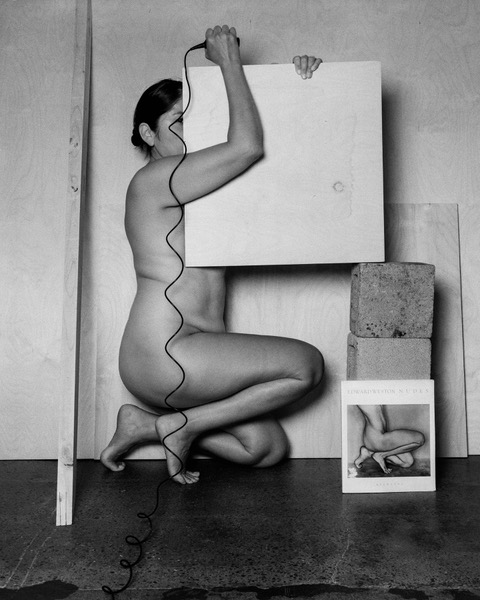

Tarrah Krajnak, Master Rituals II: Weston’s Nudes, 2020/2021, 23.8 x 18.8 cm, Museum Ludwig, Köln, © Tarrah Krajnak.

Prominently occupying the first room, Krajnak’s Master Rituals II: Weston Nudes (2020/2021), a selection of eighteen photographs, features the re-enactment of Edward Weston’s series of nudes. Taking on the role of a model, the Peruvian artist recreated poses from Weston’s highly stylized photographs. Refusing the close crop that the US-American modernist utilized in many of his nudes, Krajnak expands the lens’s perspective to expose the staging devices and studio setting. In contrast to the Levinesque idea of seamless photographic reproduction critically confounding the original with the copy, Krajnak’s ironic imitation rather highlights the difference between the canonical image and her re-articulation of it. In lieu of the idealized, passive female body she portrays the self-directed labor and process of her imperfect recreations: the strenuous posing, the wooden panel frames, and the uncomfortably hard studio floor. Forcefully holding the shutter release, the model takes control of the shot and thus evades the tight grip of the male photographer’s gaze. What is more, her darker skin tone replaces Weston’s white models, which reinforces the sense of a self-paced body breaking away from fixed modes of representation.

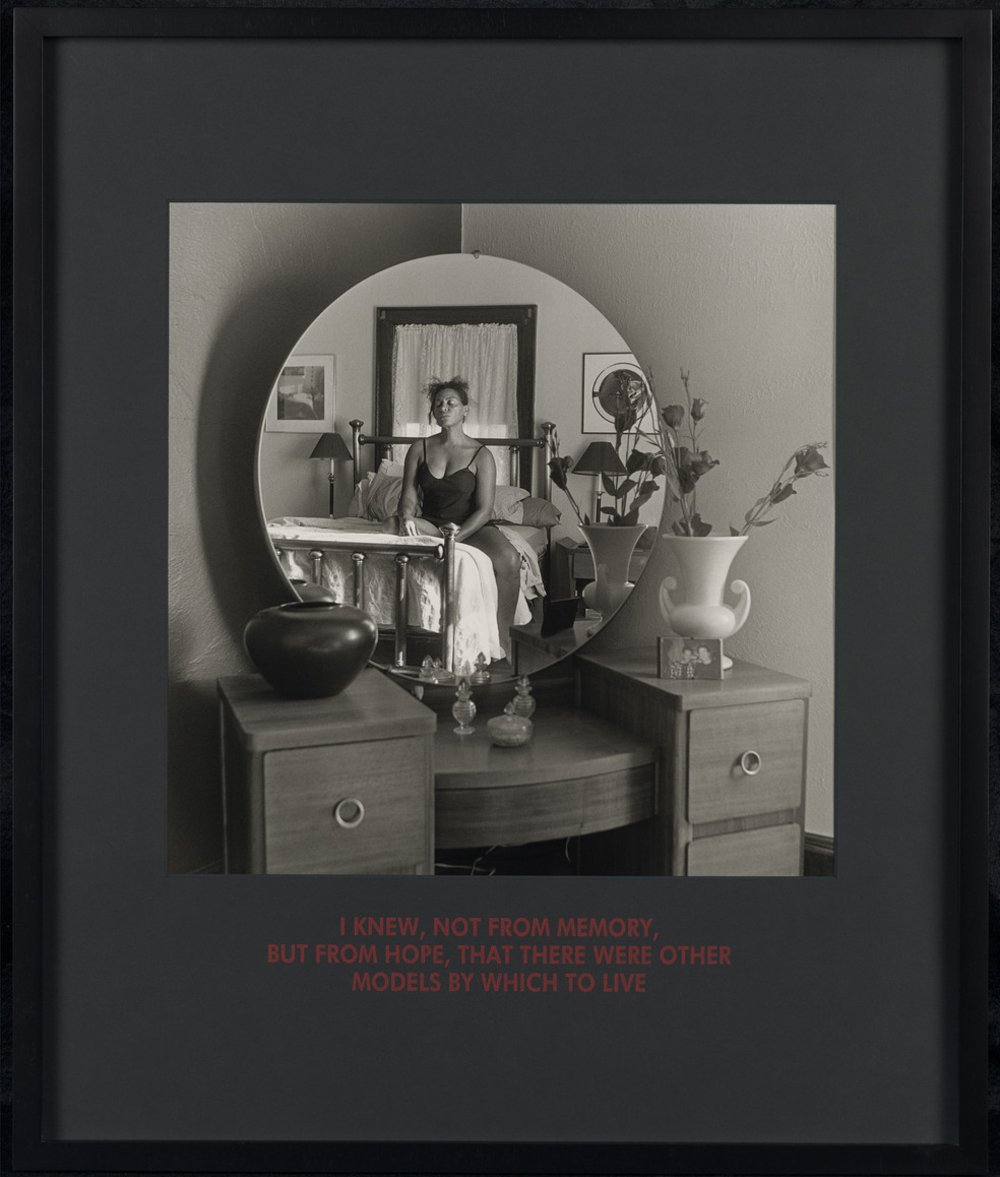

Opposing Krajnak’s piece, the African-American artist Carrie Mae Weems similarly addresses the problem of skin color in Eurocentric portraiture. Not Manet’s type (1997) documents the artist in the private setting of her bedroom, lying or leaning on the bed, nude or clad in a nightgown. Despite the intimacy of these shots, the viewer is only granted an indirect view by way of a circular mirror resting on a dressing table. On the one hand, there is a voyeuristic undertone to these images connected to the historical exoticization of black women. On the other hand, the distant fleetingness, incompleteness, and changing crops of these scenes also point to the constant threat assigned to black subjectivity and cultural reality. (See Darby English, How to See a Work of Art in Total Darkness (Cambridge: MIT Press, 2007); Tavia Nyong’o, Afro-Fabulations: The Queer Drama of Black Life (New York: New York University Press, 2019)) Weems, who is perhaps most well known for her personal portraits of domestic live(s) in Black America, adorned these complex compositions with art-historical notes in stark red letters. The series title references Edouard Manet’s infamous Olympia, a painting depicting a white and black-skinned model which has provoked much debate. As the artist Lorraine O’Grady remarked in her much-cited essay “Olympia’s Maid” (1992) the black figure of Laure reifies the “West’s construction of non-white women as not-to-be-seen.”((Lorraine O’Grady, “Olympia’s Maid: Reclaiming Black Female Subjectivity,” Afterimage 20, no. 1 (summer 1992), http://lorraineogrady.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/Lorraine-OGrady_Olympias-Maid-Reclaiming-Black-Female-Subjectivity.pdf.)) Set against this background, Weems appears to strive to articulate an alternative mode of visibility for a potentially emancipated Olympia thriving beyond the structures that mark the black woman as Other.

Carrie Mae Weems, Not Manet’s Type, 1997, 63 x 52.5 cm, Museum Ludwig, Cologne, © Carrie Mae Weems

In the following rooms, the idea of identifying and challenging representative forms of domination finds further instances. Ana Mendieta’s photography series Untitled (Facial Hair Transplants) shows the Cuban American artist gluing on facial hair – previously cut from her collaborator’s beard – to her upper lip and subsequently proudly donning her newly acquired mustache. The performance took place in 1972 and set the stage for Mendieta’s later performance works staging blood, wood, and fire, which have become emblematic for the broader movement of feminist artists exploring the body as a central venue for artistic discourse.

Ana Mendieta, Untitled (Facial Hair Transplants), 1972, 32.5 x 48.5 cm, Museum Ludwig, Cologne, © VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2023

In this context, the use of abject materials such as hair or excrement became a popular site to address the transgressive as a threat to order and meaning.(See Julia Kristeva and Leon S. Roudiez, Powers of Horror: An Essay on Abjection (New York: Columbia University Press, 1982)) At the same time, Mendieta appropriates a symbol of potent masculinity, gesturing to a joyful negation of the exclusive patriarchal claim to artistic genius and meaning.

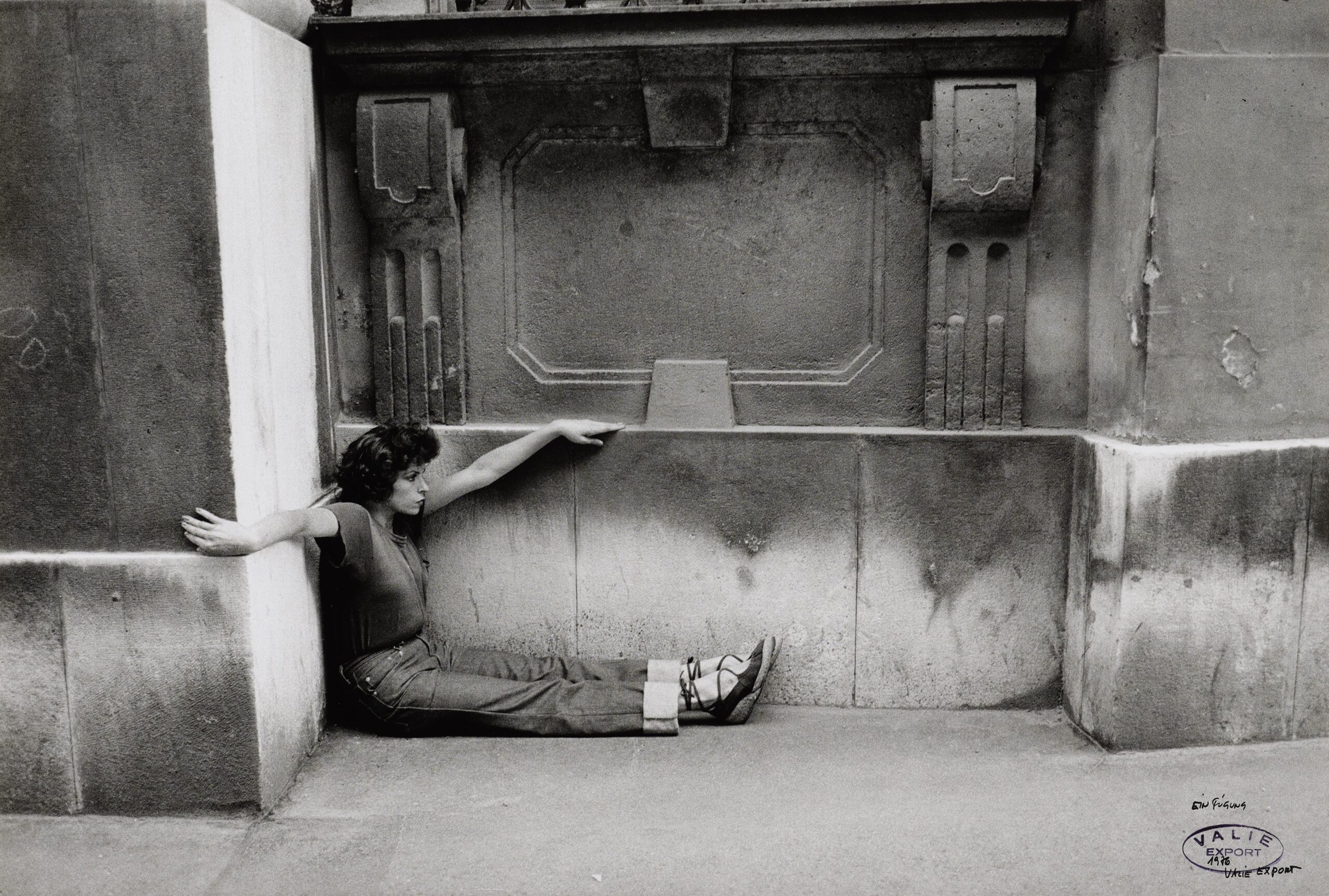

In a similar vein, the Austrian performance and media artist VALIE EXPORT explored the inhabitation of traditionally masculine forms and structures. In Körperkonfigurationen (1976) she photographed her body nestling into representative buildings in central Vienna. Reacting to the architectural forms, EXPORT, who emerged from the Viennese Actionism scene, squatted, stretched, bent, reclined, and coiled her body in different poses as if to acquiesce to the building’s dominating presence. Each shot holds a subtitle enforcing the idea of formal pressures that women’s bodies are exposed to. Consider Einfügung – here translated to Adjustment, but Insertion might have come closer to the notion of lodging a foreign body – which shows a female figure crouching in a corner of the national theater, stoically wrapping her arms around the horizontal lines of the cornerstones. The scene’s gestural bathos indicates how women struggle to assimilate into patriarchal power structures and remain excluded from its historiographies. Moreover, the staging connects to the ornamental and decorative role historically assigned to female figures in the ‘natural’ order of classical architecture and art, which the depicted figure deliberately fails to fulfill.

VALIE EXPORT, ADJUSTMENT, 1976, 41 x 61 cm, Museum Ludwig, Köln, © VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2023

In turn, Sanja Iveković’s Triangle (1979) approaches the relationship between the female body and urban architecture from a different angle. Working in the political context of socialist Yugoslavia, Iveković took photographs of an official parade, which she contrasted with a caption of herself casually reading a book on a balcony and wearing a t-shirt imprinted with the slogan “America.” Tucked away behind the anonymous balustrade, the portrayed figure casually withdraws from the collective demonstration of power, nonchalantly signaling indifference to the spectacle below. Arranged as a polyptych of four panels, the composition pits ideas of female domesticity and male publicity against each other. Yet an additional layer of meaning underpins these images which were taken not long before Josip Tito’s death ushered in a decade of intensified ethnic conflict. During many official political parades, people were advised to vacate adjacent balconies due to security concerns. In consequence, Triangle documents female privacy as much as a protest against a system of control and paranoia. The inclusion of such works underscores the regional differences in the trajectories of feminist practices where notions of retreat and being in public take on different meanings.

Thus, the body is back again. While for the last two decades, debates have gravitated towards questions of the digital and the cyborg, this exhibition returns to a more direct framing of the corporeal. By occupying both roles of model and photographer, the featured artists create ambivalent relations to seeing and being seen. Not complying with the established modes of appearance in terms of female passivity, beauty standards, or originality, the exhibited images provoke moments of disruption and distortion that throw the gaze of male-coded spectatorship back to its beholders, uncovering the powerful cultural codes limiting our identities. Accordingly, the destabilization of the gaze regime functions as a strategy to subvert and challenge its racist and phallogocentric nature.(Amelia Jones, Body Art / Performing the Subject (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1998), p. 162.) Such explorations of the photographic lens’s mirror are not limited to esoteric comments on art history but also connect to pressing political and cultural issues such as skin color, conflict, and sexual difference. In all works, the female body appears as an active and self-reflective agent questioning prevalent power structures in various political and geographical circumstances.

The selection of works responds to the frequent calls for a more pluralist and global perspective of the myriad overlapping strains of feminism, which regrettably remain relevant for the twenty-first century.(Most recently in Bryony Roberts, Abriannah Aiken, “Feminist Spatial Practices, Part 1,” e-flux, March 2023, https://www.e-flux.com/architecture/chronograms/506357/feminist-spatial-practices-part-1/.) For instance, Connie Butler’s important show WACK! Art and the Feminist Revolution (2007) still featured an overwhelming representation of cis-white women.(Carol McDowell, review of WACK! Art and the Feminist Revolution, ed. by Lisa Gabrielle Mark, CAA.reviews, September 25, 2007, DOI: 10.3202/caa.reviews.2007.87.) Although limited in size and resources, this exhibition manages to illuminate how the body became a central medium and material for artists recognizing the female body not only as a site of the reflection of systems of domination, but also their reproduction. In 1960, the psychologist Ronald D. Laing argued: “The body clearly takes a position between me and the world,” thus underscoring how the body is ambivalently situated at the core of one’s own world, as well as an object in the world of others, characterizing the corporeal as a privileged avenue of investigation and critique—an idea which resonated with the broader feminist movement.(VALIE EXPORT, Der virtuelle Körper. Vom Prothesenkörper zum postbiologischen Körper (Linz: VALIE EXPORT CENTER, 2020), p. 43: Maurice Merleau-Ponty, Phenomenology of Perception (London: Routledge, 2012), p. 150.) In addition, the show sheds light on how the feminist hijacking of patriarchal authority was not limited to a few North American metropolises and how this artistic discourse has been concerned with an intersectional approach to social justice since its inception.

It almost seems superfluous to point out the pressing cultural relevance and timeliness of the principal themes of this show. Recently, hard-fought liberal victories over women’s autonomy of their bodies are increasingly called into question such as with the overturn of Roe v. Wade in 2022. Along the same vein, intimidating protests against contested Drag Queen story hours in different European countries indicate the resurfacing of the misguided pathologizing of queer art and sexuality and its conflation with pedophilia. Conversely, the reactionary push-back against the rights of individual freedom of expression and safety overlaps with new discussions like the emergence of the highly dynamic field of trans studies, which has recently gained increasing visibility and productively expanded the horizons of established discourses. The onus on the viewer is to recognize the historical significance of the artistic protest in the politically turbulent 1970s and yet also to detect the contextual difference in the challenges we face today.

The problem with this exhibition is that the curatorial concept satisfies itself too quickly with the formula of subversion-as-liberation, disregarding the hosts of problems inhabiting it. For does the photographic act of resistance not necessarily rely on the continued presence of the dated reference point? The staged bodies only gain liberation and autonomy in constant reference to the male canon, in turn pointing to the question of what other forms and meanings could be possible outside of this opposition. In other words, turning a binary upside down is not equal to breaking it. Rather, such inversions run the danger of underscoring its structural robustness as it shows that it can withstand being put on its head. Conversely, what if we try to understand the subversion of the male gaze not as the necessary conclusion of these images – the final point, which the attentive viewer is supposed to arrive at – but rather as the creative point of departure?

One aspect that links all of the exhibited photographs is the way in which they ask viewers to consider the body beyond the realm of mere physical objecthood. Instead, the body “is to be compared to […] a work of art,” as Maurice Merleau-Ponty has suggested; an appeal that reappears as a quote at the beginning of EXPORT’s essayistic documentary film Der virtuelle Körper (1990).(VALIE EXPORT, Der virtuelle Körper. Vom Prothesenkörper zum postbiologischen Körper (Linz: VALIE EXPORT CENTER, 2020), p. 43: Maurice Merleau-Ponty, Phenomenology of Perception (London: Routledge, 2012), p. 150)) We might then, for instance, think about the geometric shapes prominently marking the displayed works such as circles (Weems), horizontal and vertical lines (Krajnak), and various trapezoid forms (EXPORT). Shapes, orders, and patterns seem to test the limits of the performing body, addressing the body not only as a problem of referentiality, but also a problem of form.(See Eugenie Brinkema, Life-Destroying Diagrams (Durham: Duke University Press, 2022)) These contortions, croppings, and fragmentations exercised as a violent pressure on the body relate to the question of how long it can remain legible as a female body. Jean-Nancy wrote of the “violence of images” as an assaultive force to the realm of representation and signification.(Jean-Luc Nancy, “Image of Violence,” in The Inoperative Community, edited by Peter Conner (Minneapolis University of Minnesota Press, 1991), p. 1-42.) From this viewpoint, the reconfiguration of the body displayed in the exhibited performances launches an attack on the confines of interpretation as such.

In consequence, the female body as a site of resistance strives to step outside binary frameworks of how bodies can be thought of and how they are allowed to appear. In recent years, crip and trans art – perspectives which are missing in this show – have productively explored and challenged the thresholds and limits of where non-conforming bodies become visible, as well as their highly charged points of intersection.(See Eli Clare, Brilliant Imperfection: Grappling with Cure (Durham: Duke University Press, 2017); Susan Stryker and Dylan McCarthy Blackston, eds., The Transgender Studies Reader Remix (New York, NY: Routledge, 2023).) Likewise, a host of exhibitions such as Kunsthal Rotterdam’s Claude Cahun. Under the Skin in 2022 or documenta 14‘s prominent feature of the German-Chilean artist Lorenza Böttner have aimed to showcase the rich history of artists working at the intersections of diverse models of gender, sex, and embodiment. This discourse is not limited to the Anglo-Saxon and Western-European sphere, but has unfolded in contexts with higher degrees of political and socio-cultural repression.(Bilić, Bojan, Iwo Nord, and Aleksa Milanović, eds, Transgender in the Post-Yugoslav Space: Lives, Activisms, Culture (Bristol: Policy Press, 2022)) For instance, the various interventions of the Polish Queer Archive Institute, the performances of the Serbian trans artist Aleks Zain, or numerous exhibitions connected to Latin American transfeminine and transmasculine movements have investigated non-normative bodies as a powerful tool for cultural critique as well as a place for potential identification and community-building on a broader scale.

The Ludwig exhibition’s foregoing of topics that have significantly transformed feminist discussions limits the inquiry of the female body to able-bodied, cisgender women. As a result, the exhibition exacerbates the gap between the time of the conception of these works and a potential commentary that speaks to the present, where the borders of “woman” as a category have moved to the center of political debates. On the one hand, this is due to the show’s limited scope in terms of resources, which characteristically plagues many collection exhibitions. Numerous larger museums regularly favor (duo-) or monographic over thematic shows, for canonical name recognition or the prospect of a novel discovery reliably promises a steady visitor flow. The Ludwig’s concurrent retrospective on the German surrealist artist Ursula Schultze-Bluhm, hailed as the first of its kind and generously occupying the two main floors, evidences this imbalance between the institutional drive to expand and the willingness to engage with what is already there. On the other hand, the omission of trans and crip perspectives stems from the complete absence in the museum’s photographic collection. Considering the recent acquisition of Tranjnak’s piece, one might wonder about the institution’s strategy to elucidate these blind spots.