Grafting Solidarities – From the Factories to the Fields

Matter of Art Biennial 2024, Prague, June 14 – September 29, 2024

Six years ago, the Czech section of the Tranzit network launched a new art biennial in Prague titled Matter of Art, currently in its third edition. In contemporary times, nearly every major city hosts biennials to foster local cultural vitality, generate tourism, and enhance the city’s international perception and influence. Each new initiative sparks inquiries into its objectives, content, and audience, at home and globally. This constant self-reflection is especially crucial for biennials in East Central Europe—such as the Biennale Warszawa, Kyiv Biennial, OFF-Biennale Budapest, and Survival Kit Festival Riga—because their national geopolitical positions remain marginalized in the international cultural field.

Installation view of Matter of Art Biennial 2024, National Gallery Prague – Trade Fair Palace. Photo © Jonáš Verešpej. Courtesy of Matter of Art Biennial.

The third Matter of Art Biennial explores a decidedly unconventional and refreshing theme in the international biennial universe: Rural change as social change, and the legacies and futures of worker’s movements. The international curators—Hungarian Katalin Erdődi and Belarussian Aleksei Borisionok, both known from the Vienna scene—chose to focus on “the working class and the rural,” terms that are heavily charged, especially when framed in the context of “ending exploitation and injustice” and seeking a “vision for the future.” The biennial guidebook’s communist-revolution-red cover—with the title stamped with symbols such as a hammer, a sickle, a raised fist, a book, and wheat—leaves nothing to chance with the audience’s imagination. One might assume that some neo-Marxist revolutionary vision is about to unfold through the exhibition on view. Ultimately, however, the biennial fails to fulfill this promise, which is already foreshadowed by the curatorial statement. While the curatorial manifesto is brief, there are narrative elements (alongside explicit Marxist references) that position the rural as the oppressed, silenced, and voiceless—which in turn needs to be voiced through the art biennial. Paralleling the rural and the working classes with the colonized subalterns—highlighting terms like “resilience”—might well participate in a kind of essentialism that is the exact opposite of any change, not to mention revolution. Meanwhile, in practice, the implied curatorial self-positioning—and that of the broader cultural field—comes across as simultaneously unreflective, romanticized, and paternalizing. For confirmation, we need only look at voter behavior in the Global North over the past decades: election maps and results demonstrate that the voice and will of the rural is expressed rather clearly in opposition to the urban intellectuals. It is precisely to that geographic and socioeconomic sphere that the curators, the artists, the critics, most of the audience, and indeed the biennial exhibition as a genre belong.

Matter of Art Biennial 2024 exhibition guidebook. Courtesy of Matter of Art Biennial.

The Matter of Art exhibition is housed in a spacious, high-ceilinged hall of several hundred square meters in the modern collection of the National Gallery in Prague. This space presents two main challenges: it lacks any sectional structure, and anything at the human scale gets lost in the concrete-grey expanse. The designers, Dominik Lang and Adéla Vavríková, addressed these issues using wooden transmission poles reminiscent of rural landscapes, truck tires, upside-down beer crates, and ytong brick and plank structures familiar from backyard gardens. Despite the sensation of tactile discomfort that these materials produce, Lang and Vavríková’s structure is a brilliant achievement, creating a sense of unity and continuity in the space. However the labyrinth of works hanging from the ceiling cannot create the feeling of sectional, thematic units—which seems to be one of the core idea of the exhibition—and unfortunately, the works hardly enter into a conversation with each other. The selected pieces pose another challenge: for the most part, the exhibition does not address the working class in terms of the factory workers mentioned in its title at all. The only seriously interesting work on the subject is Giorgi Gago Gagoshidze’s beautifully directed video The Invisible Hand of My Father (2018). The piece draws a quite poetic parallel between the invisible hand of the market replacing the ideologically existing collective socialist workers’ hands and the artist’s father’s amputated hand (lost in a factory accident as a post-socialist migrant worker in the West). The final twist to this tale of economic vulnerability and the dishonor of migrant labor is that now the invisible, non-existent, amputated worker’s hand puts bread on the Georgian table from a Western disability pension.

Moving from the factory to the rural, the exhibition expands in many ways. The curators’ choice and understanding of the term is not overexplained. It appears simultaneously as a reference to non-urban geographical locations, to the people who live there, and to those agricultural workers who are supposedly the descendants of the peasantry, carrying the transgenerational knowledge and experiences (in the last case primarily referring to the dissolution of the peasantry).

Giorgi Gago Gagoshidze, The Invisible Hand of My Father, 2018. Matter of Art Biennial 2024, exhibition view, National Gallery, Prague – Trade Fair Palace. Photo © Jonáš Verešpej. Courtesy of Matter of Art Biennial.

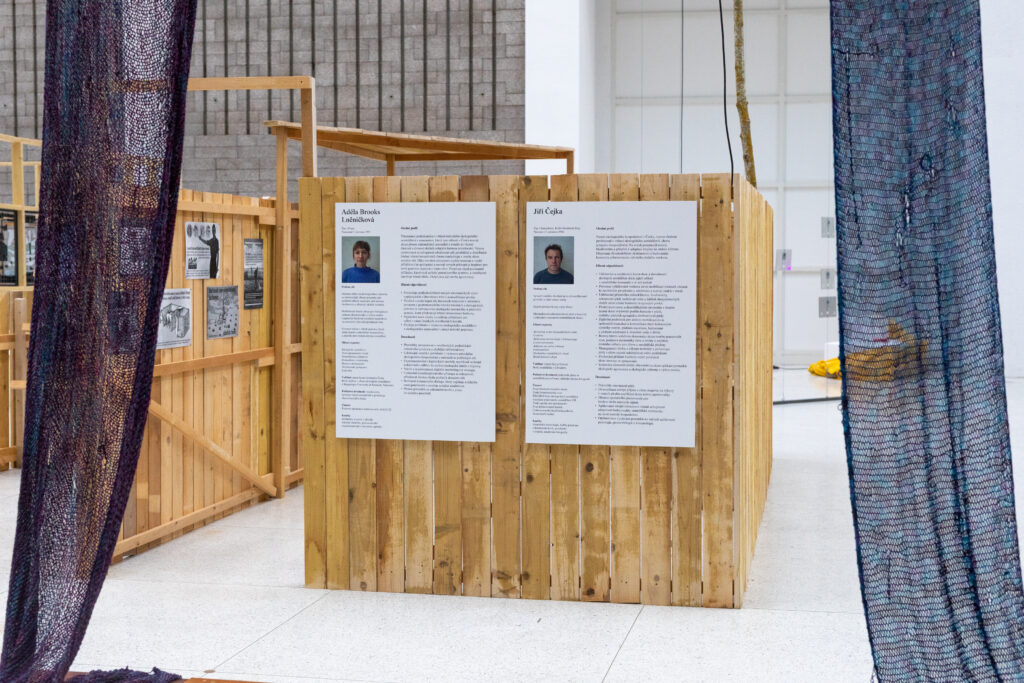

Asunción Molinos Gordo’s works were an excellent choice to introduce the visitors to the potential richness of the rural theme. Her perfectly chosen mediums and crystal-clear messages mobilize a dazzling array of social, cultural, and political layers, all seen through a transglobal perspective. In her Peasant CVs (2015-ongoing), Gordo uses the aesthetics and language of corporate CVs to highlight the skilled work of peasants. Using formal bureaucratic vocabulary, Gordo satirizes the rhetoric of conservation practices led by governments and NGOs while emphasizing the transgenerational accumulation of expert knowledge gained through centuries of experience. In her other piece, The Peasant Has a Hoe (2013), builds upon Gordo’s observation that in Arab calligraphy lessons, the example sentences children must copy often feature “a peasant” as their subject. She transformed a row of lined schoolpapers into the chronology of the radical changes of the peasant life’s and coercion in post-industrial times: starting with sentences such as “the peasant eats roasted pigeon,” only to quickly arrive at “Irrigation water gets privatized,” “The fertile soil starts to turn into desert,” and “The peasant does not want his children to become farmers.” In her third work, Ghost Agriculture (2018), Gordo has created infographics using an Egyptian patchwork technique, layering the stylized images of traditional and sustainable small-scale diversified farms feeding the population with the artificially created corporate farmlands in the desert growing crops for export.

Asunción Molinos Gordo, Peasant CV, 2015–ongoing. Matter of Art Biennial 2024, exhibition view, National Gallery, Prague – Trade Fair Palace. Photo © Jonáš Verešpej. Courtesy of Matter of Art Biennial.

Surrounding and following Gordo’s work, the largest middle section of the exhibition addresses the issues of farming, and communal societal un/sustainability through interventions that are more didactic than artistic. Among these, only Tomáš Uhnák’s The Spectre of Peasantry (2024) stands out. Uhnák reflects on the challenges farmers face—land grabs, displacement, and other forms of violence—while focusing on proactive solutions. He exemplifies this with the United Nations Declaration of the Rights of Peasants and Other People in Rural Areas (UNDROP), adopted by the UN General Assembly in 2018 after 20 years of citizen advocacy. In Uhnák’s video, Czech farmers read sections of the declaration that they consider most important. In a parallel video, they discuss which words best describe the work they identify with in terms of political and social recognition. This turn to personal identification is an intriguing contrast with the exhibition’s implied references to “class consciousness.”

While some works are strong enough to carry their message, the loose application of the word rural (or working class) becomes confusing when looking at the works collectively. The open definition of “rural” that seemed favorable in the exhibition manifesto is not enough of a frame to hold together the dozens of artworks installed in the same space in a conceptually productive or consistent way. The curators explain their approach as grafting—planting different thoughts next to each other, a definition that could also serve as the concept of any group show ever curated—the selected works are so disparate from each other that the viewer easily loses the connections between them.

Tomáš Uhnák with Asia Dér, Tamás Kaszás, Asunción Molinos Gordo, The Spectre of Peasantry, 2024. Matter of Art Biennial 2024, exhibition view, National Gallery, Prague – Trade Fair Palace. Photo © Jonáš Verešpej. Courtesy of Matter of Art Biennial.

What connection , for example, could one find between the paraphrased neo-folk tradition of figurative village fences by the Hungarian Randomroutines, Belarussian Uladzimir Hramovich’s fountain composition referring to the uprising in the salt mine city of Salihorsk, and Berlin-based Alicja Rogalska’s local-TV-slot-like videos about ethical local flower-arrangement consumption? Between Czechoslovak Petr Štembera’s 1970s happenings (body art performances documented in black and white photographs), Marta Popivoda’s installation referring to the Lidice massacre by the Gestapo in 1942, and so on? While the potential of many works shines through, the larger-than-life space, with its seemingly random context and associations, undermines the aura of the pieces. Also, there appears to be not even the slightest understanding (or explanation), of what many of the pieces have to do with Marx, movements, or the possible political emancipation of the future—which the curatorial statement identifies as the core ideas of the exhibition.

The lack of dynamics necessary for the change promised by the curatorial text is exemplified by the exhibition’s exceptionally powerful concluding artist trio. After the confusingly eclectic middle section, Nikita Kadan’s Dream Flags (Dolyna Sculptures) (2024)—bullet-torn metal flags formed from the material collected in the Dolyna battlefields combined with notes from Kadan’s war-dream journal—vividly evoke the suffering of the Ukrainian land and its people. They pair beautifully with Kateryna Aliinyk’s paintings: close-ups of landscapes—roots, trees, and bugs resembling human innards—that depict mortality and decay, made all the more realistic when read against the current political and war-torn climate. Complementing them, the closing piece of the exhibition’s final display is Hungarian artist Dominika Trapp’s shrine-like sound and object installation, Lay Him Not Upon Me (2020), framed by coffin-velvet curtains. Trapp tells the story, collected in the 1970s, of a peasant woman, whose first and last act of defiance against her tyrannical husband was to ask her children not to lay the husband’s body atop hers in the grave.

Nikita Kadan, Dream flags (Dolyna sculptures), 2024. Matter of Art Biennial 2024, exhibition view, National Gallery, Prague – Trade Fair Palace. Photo © Jonáš Verešpej. Courtesy of Matter of Art Biennial.

With this ending, the curators have grafted together a rather uninspiring non-vision of the future, one that was already forecasted during the exhibition opening, when an activist group of artists staged a performative act by placing an uprooted olive tree in the exhibition space, conceptually allowing it to die over the ensuing weeks as a gesture of solidarity with Palestine. The defeatist tone of this gesture sums up the exhibition as a whole: while it highlights problems and suggests some potential solutions, it ultimately conveys a sense of inevitable demise. Maybe at best, on our deathbeds, we might dare to raise our fists to the ones above and whisper, “Fuck y’all.” It is not very uplifting, nor does it impactfully envision any change, let alone revolution.

Intriguingly, an exhibition about the rural and the working class in East Central Europe, apart from the hints in the curatorial manifesto, lacks any significant presence of or references to Marx, to the failed and dissolved Marxist-Leninist political and cultural traditions, or to the region’s influential theorist of revolutionary art, Georg Lukács. The political and cultural past shaped by state socialism, and its rich tradition of worker-peasant representation in a revolutionary context, is absent. This omission is surprising, given the region’s history of three waves of dismantling peasant life: the industrial revolution, the rapid and forced modernization during state socialism, and the swift shift to capitalism post-regime change, which eradicated the remaining existing communities. The total absence of artistic reflections on these transformative changes, especially the tradition of socially mobilized peasant and working-class writers and artists active before and after the regime change, is particularly striking.

We must also address the question posed by the biennial’s name itself: what is the “Matter of Art”? The curators apparently did not ponder this question, either in the exhibition space or in the accompanying reader. The softcover book includes no theoretical texts to support or expand the exhibition. It instead includes some interviews and artists’ roundtable transcriptions that provide interesting details, but miss the overarching understanding of the exhibition’s theme or aims. For example: should art speak about people’s lives or aim to improve people’s lives in the name of political or socially relevant ideologies? If the exhibition had shifted its focus from the latter to the former, and if the iron fist and communist red were removed from the project’s visual identity, the curatorial selection would have made almost perfect sense.

However, if the connection between art and revolution is to be maintained, it would indeed have been worth revisiting and reflecting on the Lukácsian dilemma: can art provide a future perspective? Or further, another question that was beyond of Lukács’s crisis of thought: can curators provide a future perspective? Although some of these intellectual traditions and considerations—combined with the historical lived experiences of the East Central European rural and working classes and their relation to the intellectual elite—are highly specific, reviving them would nonetheless resonate with and enrich the current national, regional, and international discourses.

Dominika Trapp, “Lay Him Not Upon Me…” – The Body of a Peasant Woman, 2020, exhibition view, Matter of Art Biennial 2024, National Gallery, Prague – Trade Fair Palace. Photo © Jonáš Verešpej. Courtesy of Matter of Art Biennial.