Ghosts in the Machine: Exposing the Margins of the Bauhaus

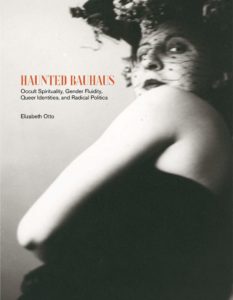

Elizabeth Otto, Haunted Bauhaus: Occult Spirituality, Gender Fluidity, Queer Identities, and Radical Politics (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2019), 280 pp.

Whilst attempts to decenter art history have frequently focused on bringing to the fore marginal movements or places, an equally useful approach is reassessing those practices symbolically located in the center. As any historian of modern design knows, it is impossible to ignore the specter of the Bauhaus hovering unnervingly over any other design institution of the interwar period, especially those belonging to the peripheries. In her new book, Elizabeth Otto turns the tables and haunts the Bauhaus itself, unravelling a host of marginal practices and practitioners that change the way we perceive this icon of modernity. As the subtitle of the book reveals, she tackles four different areas: Occult Spirituality, Gender Fluidity, Queer Identities, and Radical Politics.

The first chapter outlines the underpinnings of the book’s premise, introducing different modes of haunting. One is metaphorical and methodological, rooted in Avery Gordon’s Ghostly Matters: Haunting and the Sociological Imagination, which proposes the analogy of haunting for that which has been repressed and yet seeks to makes itself known.(Avery Gordon, Ghostly Matters: Haunting and the Sociological Imagination [1997] (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2008).) Another is much more literal, referring to the impact of spiritualism at the Bauhaus. As Otto herself recognizes, this is somewhat familiar ground. In particular, the influence of Johannes Itten and his espousal of Mazdaznan—a syncretic faux-Eastern ascetic movement—are now well known in the context of the institution’s early years. For example, Die Neue Zeit (2019, dir. Lars Kraume), a German television series made to coincide with the Bauhaus centenary, chose to focus on this period, depicting Itten’s regimen of bodily purges and esoteric mental and physical exercises. It also depicted Gertrud Grunow’s Harmony Course, which taught students to explore the connectivity between movement, sound, and color. As Otto reveals, Grunow was “the only woman ever to attain this highest title for a teacher during the school’s early years,” and to be included in the masters’ council meetings (p. 34). Because Grunow is rarely mentioned in this context (unlike Itten, Klee, or Kandinsky, whom Otto also discusses), the recovery of Grunow’s synaesthetic philosophy and her impact at the Bauhaus is one of the highlights of this opening chapter.

However, Otto’s attempt to extrapolate these spiritual practices to the Bauhaus’s later years is perhaps the volume’s weak point (and probably the only one, it must be said). Otto’s argument hinges on the mechanical light installations created by Ludwig Hirschfeld-Mack and subsequently László Moholy-Nagy, as well as various experiments that Bauhäusler carried out with double exposure, resulting in seemingly “ghostly” photographs. Both of these practices were more likely inspired by experimentation with new technologies and the possibility of mechanizing artistic production, rather than a throwback to the age of spirit photography and occult occurrences. In a subsequent chapter, Otto herself discusses one of Marianne Brandt’s double-exposed photographs as an attempt to create a self-portrait as artist-engineer and to “evidence [her] technical skill as a photographer” (p. 75). But perhaps to quibble about the division between the spiritual and the rational is to fall prey to the parameters imposed by the center’s vision of modernity. Indeed, the (imagined) East’s (imagined) propensity for esotericism is often utilized to attest to its incompatibility with Western modernity, while the influence of Eastern thought on the Western avant-gardes is often minimized, as Partha Mitter has observed.(Partha Mitter, “Decentering Modernism. Art History and Avant-Garde Art from the Periphery,” The Art Bulletin 90:4 (December 2008): 531–48.)

This uneasy relationship is exemplified by the lowly status of Expressionism within the trajectory of the Bauhaus in comparison to “rational” movements such as Constructivism, a relationship tangentially explored in Chapter 2 through the lens of masculinity. The artist-engineer and his shadowy alter-ego—represented by Conrad Veidt’s cinematic antagonists—are revealed to be two facets of the same post-war masculine identity, rather than dichotomous typologies. After all, Expressionist cinema and theatre created some of the most enduring artistic responses to modern technology, from Fritz Lang’s Metropolis and Frau in Mond to Karel Čapek’s R.U.R. Even in 1929, when the Bauhaus had supposedly surpassed its Expressionist roots, T. Lux Feininger photographed Karla Grosch, the women’s gymnastics instructor and one of Oskar Schlemmer’s dance performers, in the guise of “a futuristic goddess” that harked back to Metropolis’s robotic main character (p. 76).(Although this might have been a two-way influence, with Lang inspired by Schlemmer’s earlier Triadic Ballet.)

Chapters 2, 3, and 4 are interlinked, focusing on gender at the Bauhaus. While Chapter 2 dissects different facets of masculine identity, Chapter 3 focuses on how female Bauhäusler depicted themselves, and Chapter 4 reveals those who “queered the school’s aesthetics” (p. 9). This core section of the book is its strongest element, with each chapter highlighting little-known artists or artworks. From the moment we are presented with a photograph of Marcel Breuer as a playful Duchampian cross-dresser, we know that we are in for a wild ride. The art of photomontage reveals its crude side through Herbert Bayer’s elaborate 50th-birthday gift to Walter Gropius, which playfully referenced the affair Bayer was having with Ise Gropius, Walter’s wife. In one spread, the Bauhaus’s director is depicted amidst a baroque excess of lush nudes and luxuriant fruit, whilst in another he is embodied by a muscular nude brandishing paper and an architect’s triangle, while “a pencil of epic proportions,” as Otto puts it, hangs from his waist (p. 85). Marianne Brandt, usually known for her metal objects, is also revealed in a different light. Her experimental photographic self-portraits utilize the reflective and distortive potential of metallic balls, as well as hovering between self-representations as elegant ingenue or lab-coat-wearing engineer. Then there is Renate Richter-Green, later known as Ré Soupault, who after training at the Bauhaus for two years went on to create multi-purpose women’s clothing, engage in avant-garde film-making, and produce insightful reportage photography. Cameraless after escaping the Nazi regime, Soupault took an arresting image of herself and her companions in a Buenos Aires amusement park by triggering a photographic mechanism with an air gun. Max Peiffer Watenphul was adept at both weaving and taking extravagantly decadent photographs that might now be termed camp, writing gleefully to a friend in 1932: “Made brilliant new photos. But people say they’re very perverted!!!?” (p. 147). But probably my favorite discovery from the book is Margaret Camilla Leiteritz, who not only designed many of the Bauhaus’s commercially successful wallpaper patterns, but also went on to live her life as an unmarried librarian—a “singleton”, as Otto calls her, although Leiteritz was clearly no Bridget Jones—making Beardsley-esque illustrations with sapphic undertones in her spare time. This cavalcade of atypical Bauhäusler makes for engrossing reading, with Chapter 4—the chapter dedicated to the Bauhaus’s queer “ghosts”—the strongest one in the book. The artists listed above are only a sample, with many other captivating and sometimes tragic trajectories outlined in the volume.

What becomes apparent from this examination of queerness and gender fluidity at the Bauhaus is how conventional an institution it was. I am uncertain whether Otto would share my conclusion, as her aim is to reveal the diversity of those formed at the school, but it seems to me revealing that most of this non-conformist artistic production was created once students had left the Bauhaus. Indeed, Otto uncovers an instance of a transgender student being refused entry to the school in 1920, and of a lesbian student leaving the Bauhaus when an affair with another student became public knowledge (p. 142). Furthermore, women at the Bauhaus faced other discriminatory behaviors familiar to us, such as pay inequality, hazing, and what is now colloquially known as mansplaining. Otto reveals how Gunta Stölzl, who was the first female master of the Weimar period, “was given an inferior title for the same work and received less pay than her male counterparts—even once she too received the title of junior master” (p. 101). After joining the metal workshop, Marianne Brandt was deliberately given mundane tasks in the hope that she would quit, and even after eventually becoming the workshop’s master she had to defend her approach in writing in the face of critique by artist Naum Gabo—a guest lecturer at the Bauhaus in 1928—who thought she should be running it differently.

Moreover, the Bauhaus purposely eschewed gender equality from the very beginning. When the school opened in 1919 women students outnumbered the men, causing the masters’ council to impose an unofficial admissions quota: henceforth, women were under no circumstances to constitute more than one third of the student body. According to Otto, the reason for this decision was Gropius’ fear that the institution would not be taken seriously and would be accused of “dilettantism.” Gropius was probably right about this, not only with respect to his contemporaries, but also with regards to the Bauhaus’ place in the history of art and design. For example, one of my own research interests is the Reimann school, a Berlin institution that pre-empted many of the Bauhaus’s pedagogical innovations, as well as employing a whole host of female instructors and supporting its many female students with bursaries and employment opportunities. The Reimann is hardly ever present in histories of modern design, despite its progressive teaching and policies, and in its time was unfavorably compared with the Bauhaus, which “gave a ‘hard-working and experimental impression,’ [while] the Reimann was ‘a bit like a finishing school.’”(Yasuko Suga, “Modernism, Commercialism and Display Design in Britain,” Journal of Design History 19:2 (2006): 137–154, at 140.)

All scholars of the marginal have at some point been at the receiving end of what Avery Gordon calls the societal “commitment to blindness: to be blind to the words race, class, and gender.”(Gordon, Ghostly Matters, 206–207, quoted by Otto at 129.) Discussing this, Otto remarks: “Considering how the markers of difference have been uncritically permitted to stake out a boundary between who matters and who doesn’t for a movement’s history, who defines that movement and who doesn’t even register in its definition, who is authorized as an innovator and who isn’t, allows us potentially to pry that history free from its well-worn track” (p. 129). The issue of “who matters and who doesn’t” in art history is brilliantly skewered in comedian Hannah Gadsby’s award-winning show Nanette, a suitable pop culture pendant, it strikes me, to the Haunted Bauhaus, with its themes of queerness and marginality. A former art history major, Gadsby does what few professional art historians would have the temerity to do: she asks why Picasso and his invention of Cubism should matter more than the women whose lives were subsumed or even destroyed in the artistic process. This of course is only one of myriad of examples of avant-garde practices cannibalizing the weak and marginalized, yet claiming to be revolutionary forces. The assumption of resistance, or what James Harding terms “the versus myth” in The Ghosts of the Avant-Garde(s),(James M. Harding, The Ghosts of the Avant-Garde(s). Exorcising Experimental Theater and Performance (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2013).) another book about methodological hauntings, has frequently been used to keep modern movements from geographical peripheries out of the canon.

Nonetheless, the many artistic innovations of the Bauhaus did not translate into a progressive stance when it came to social matters, or even political matters in some cases. Chapter 5 examines the school’s connections to both communism and fascism. Whilst the Bauhaus’s left-wing leanings are fairly well-documented, Otto’s revelation that right-wing ideologies showed their influence at the school is rather more surprising, with a group of students even painting a swastika on Gunta Stölzl’s studio door.(Stölzl was married to Jewish architect Arieh Sharon. Although Otto does not mention this, the Mazdaznan doctrine could also be construed as advocating racial purity. See Pádraic E. Moore, “A Mystic Milieu: Johannes Itten and Mazdaznan at Bauhaus Weimar”, bauhaus imaginista, http://www.bauhaus-imaginista.org/articles/2210/a-mystic-milieu (accessed April 16, 2020).) After the Bauhaus’s closure by the Nazi regime, some of the school’s former members participated in state sponsored events such as the 1934 exhibition German People—German Work (Deutsches Volk—Deutsche Arbeit), which included work by Lilly Reich, Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, Walter Gropius, and Joost Schmidt. Other Bauhäusler such as Herbert Bayer and Ilse Fehling actively put their design skills in the service of the Nazi regime, but surely the most horrific career progression was that of architect Fritz Ertl, who became head of planning during the construction of the Auschwitz concentration camp.

Despite all this, it is not my intention—and it is certainly not Otto’s stance—to produce a critique of the Bauhaus itself or its production. Instead, it is to challenge how art historical discourse perceives the Bauhaus and other established symbols of modernity. To write about the center effectively, Otto proposes, “we must acknowledge not only the operations that have been at work to give us a faulty understanding of the past, we must also recognize that, in repeating those old histories, we participate in a foreclosing of potentially more fruitful futures” (p.130). Impeccably researched and compellingly written, Haunted Bauhaus forges a path towards one such promising art historical future.