“Ende statt Wende”: Ruth Wolf-Rehfeldt’s Typewritings and the Critique of German Reunification

When checking the mail in either of the two Germanys in February 1990, one might have expected to find the usual mixture of bills and junk, as well as personal correspondence and official letters. More unusually, the mailbox might have contained an SOS message: “This is a cry for help!” Written as a plea for support, notably in English, this short text called on individuals to write to the parliamentary bodies of the German Democratic Republic (GDR) and Federal Republic of Germany (FRG), and decried the destruction of “social circumstances and rights” in the GDR. This distress signal had been sent amidst the Wende, the immense political transition following the fall of the Berlin Wall on November 9, 1989. From that moment onwards, the drive towards reunification proceeded at a brisk pace. By August 31, 1990 the Unification Treaty had been signed, and on October 3 it effected the dissolution of the GDR and its dictatorial government. The text conveyed no illusion that the FRG and GDR were “equal partners” in that process. Framed in the language of political advocacy, and deploying the anti-imperialist language of “occupation,” the SOS was not the work of a political activist, as might be expected, but rather that of the artist Ruth Wolf-Rehfeldt.

Ruth Wolf-Rehfeldt, SOS Mail Art Action, 1990. Photocopy with original rubberstamps, 8 17/64 x 11 11/16 in. (21 x 29.7 cm). Artwork © Ruth Wolf-Rehfeldt. Courtesy of Museum of Fine Arts – Artpool Art Research Center, Budapest, 2024.

Since the early 1970s, Wolf-Rehfeldt had been producing what she termed “typewritings.” These unconventional prints, made with an Erika typewriter, incorporated various arrays of alphanumeric characters. Her designs ranged from the declarative to the disorderly, from those that foregrounded the linguistic and acoustic dimensions of language to those that emphasized the visual qualities of the typewritten mark. To execute this vast body of work she relied on the expert skills she had cultivated as an office worker at the Academy of Arts during the 1960s in East Berlin. This training enabled her particular combination of dedicated labor and practiced virtuosity.(Benjamin Rux, “Manifest Der Freiheit: Die Künstlerin Ruth Wolf-Rehfeldt,” in Ruth Wolf-Rehfeldt, ed. Benjamin Rux.(Dresden: Sandstein Verlag, 2021), 8–20; Sven Spieker, “Ruth Wolf-Rehfeldt’s Typewritings Between Labor and Virtuosity,” in Für Ruth – Der Himmel in Los Angeles, ed. Kathleen Reinhardt [Leipzig: Spector Books, 2021], 33–51) Her works not only probed the affordances of the typewriter, which emblematized the disciplining of communication in modernity, but were also made for circulation through the international mail art network.(Paola Malavassi, ed., “Mail Art for Overcoming the Borders of Systems and Countries: A Conversation with Kornelia Röder,” in Ruth Wolf-Rehfeldt: Nichts Neues [Berlin: Hatje Cantz, 2023], 92–102) Understood as vehicles for renewing collective bonds as well as formal and semantic exercises, her works signal a deep commitment to the inextricable bond between artistic practice and social circumstances.

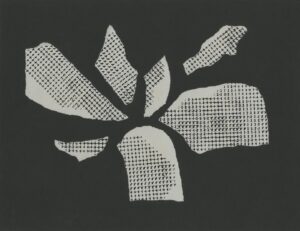

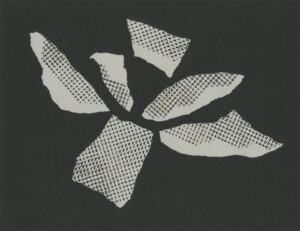

Ruth Wolf-Rehfeldt, Destruction, 1990. Typewritten black ink on paper, collage on black cardboard, 11 1/4 x 14 3/16 in. (28.5 x 36 cm). Artwork © Ruth Wolf-Rehfeldt. Courtesy of the Centre for Artists’ Publications / Fonds Ruth Wolf-Rehfeldt. Weserburg Museum für moderne Kunst, Bremen.

That commitment made the events of the Wende all the more pressing. It was no coincidence that in 1990 Wolf-Rehfeldt produced the bleakest work in her oeuvre. The hope cautiously ventured in the SOS was eviscerated by the bluntly titled Destruction. Torn pieces of typewritten prints were pasted down on black cardboard, giving an object lesson in the shattering supports of linguistic exchange.

These two final works provide contrasting poles through which to filter the currents that animated Wolf-Rehfeldt’s artistic practice amidst the collapse of the GDR. While SOS holds out the possibility of mobilizing the mail art network for continued collective action, Destruction materially fragments the typewritten prints that had comprised the core of her practice for the previous two decades. In the wake of her passing in February 2024, a reflection on her career during this fractious period illuminates the critical position that she took vis-à-vis the process of reunification and its ramifications for artistic practice predicated on socialist principles of solidarity and camaraderie. What emerges is an understanding of her terminal work as striated by international connections as much as it was bound up with the contested developments surrounding the Mauerfall.

The Social Art of the Typewritten Page

Working from her home studio in East Berlin, Wolf-Rehfeldt was a prolific participant in a transnational group of artists who took the postal system as their vehicle for artistic distribution and, not infrequently, object of criticism. Above all for these artists, what mattered were principles of inclusion and reciprocity. Anyone who could send mail could participate by distributing work, at least in theory. Access to technologies for reproducing work, such as xerography or lithography, were not always readily available to artists, especially those working in political conditions marked by extensive state surveillance.(Klara Kemp-Welch, Networking the Bloc: Experimental Art in Eastern Europe 1968-1981 [Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2018], 93) Nevertheless, a basic emphasis on reciprocation powered the network. Those involved would send on their work, often included with correspondence and other personal notes, and invite replies in return.

At times, key aspects of the postal system provided motifs. In To (1974), for instance, Wolf-Rehfeldt puts a witty spin on the envelope. Unmarked paper stock appears where addressee information and postage stamps would generally be written, while she repeats and rearranges the eponymous word to forge the “envelope.” This figure and ground reversal conjures the usual carrier of her work, and suggests that the postal system was not merely a neutral conveyance but a channel shaped by communicative acts.

Part of what makes Wolf-Rehfeldt’s deft formal exercises so striking is that they functioned in an artistic milieu that lent great weight to the generation and reproduction of social relations. Mail artists’ emphasis on social as opposed to economic relations is difficult to overstate. This loose affiliation of artists, whose connections stretched from East Berlin to Buenos Aires and Warsaw to New York, often couched their activities in terms of a resistance to the demands of the commercial market for art.(On the extent of the mail art network, and its variously ambivalent and resistant relations to commercial imperatives, see Miriam Kienle, Queer Networks: Ray Johnson’s Correspondence Art [Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2023]) In a short essay from 1976, her husband Robert Rehfeldt stressed that contact, or at least its possibility, served as a precondition for expressions of socio-political solidarity beyond market or institutional imperatives.(Robert Rehfeldt, “Ursachen Und Wirkung Der Kunst in Der Kommunikation – Die Mitteilung Progressiver Ideen per Post,” in Mail Art Szene DDR, 1975-1990, ed. Friedrich Winnes and Lutz Wohlrab [1976; repr., Berlin: Haude & Spener Verlag, 1994], 15) Such claims were valid up to a point, given that the by the 1970s major exhibitions of mail art had been held in New York, Paris, and São Paulo and collectors were increasingly active in the field.(These exhibitions were: New York Correspondence School Exhibition (1970) at the Whitney; the Section des Envois at the Paris Biennale in 1971; Poéticas Visuais [1977] at the Museu de Arte Contemporânea da Universidade de São Paulo; and a mail art section included in the XVI Bienal de São Paulo,1981) For Wolf-Rehfeldt, claims for solidarity also meant challenging traditional gender roles and hierarchies. Although male artists dominated the mail art network, it still provided her with contact to female artists within and outside the GDR, such as Karla Sachse, Ingrid Behm, Anna Banana, and Claudine Barbot, among many others.(Sarah E. James, Paper Revolutions: An Invisible Avant-Garde [Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2022]), 292–94. On the contestation of patriarchal conceptions of femininity in the GDR, with particular attention to female artists’ negotiation and formation of alternative gender roles and identities, see Angelika Richter, Das Gesetz Der Szene: Genderkritik, Performance Art und zweite Öffentlichkeit in der späten DDR [Bielefeld: Transcript Verlag, 2019]) Participation offered a way to break from traditional expectations of domestic confinement and the gendered politics of the typewriter, and Wolf-Rehfeldt did so by maintaining her own voluminous correspondence and advancing her own distinctive approach to these concerns over commodification.

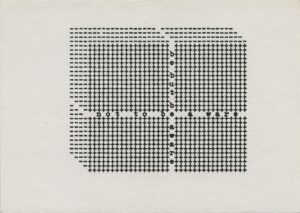

In one postcard-sized print, the restrained use of typed characters gives the impression of a wrapped parcel, along with its eponymous slogan: “be but aware not to be a ware.” Given Wolf-Rehfeldt’s own bilingualism, it recalls both the general English notion of a “ware,” as a manufactured item offered for sale, as well as the more specific German Ware(“commodity”). Addressed to recipient-readers in the imperative mood, it cautions against subsumption in chains of commercialization. It at once refers to the circulation of items through the post and bolsters connections between individuals in the mail art network.

Ruth Wolf-Rehfeldt, Be But Be Aware Not To Be A Ware, 1970s. Zincograph, 4 1/8 x 5 11/16 in. (10.5 x 14.5 cm). Artwork © Ruth Wolf-Rehfeldt. Courtesy of the artist and ChertLüdde.

The prime if idealized importance of mail art lay in the absence of an instrumental type of communicative exchange. Aspiring to the status of “relations without purpose,” as Theodor Adorno wrote of the possibility of non-commodified bonds between people, these links were fostered over many years through works freely given.(Theodor W. Adorno, Minima Moralia: Reflections on a Damaged Life, trans. E. F. N. Jephcott [1951; repr., London: Verso, 2005], 41) When seen in such terms, the combination of open involvement and reciprocal exchange became a cooperative and dispersed project of generating and renewing social bonds. And generative those practitioners were. Over the decades, Wolf-Rehfeldt and Rehfeldt received thousands of pieces, from birthday well wishes and greeting cards to original prints and collages. As is common in the art world, those long-distance relationships were never entirely devoid of career opportunities. At least for some well-connected artists, especially those working in the Eastern Bloc and parts of Latin America, the mail art network enabled them to achieve a level of international visibility that was otherwise often foreclosed.(Kemp-Welch, Networking the Bloc: Experimental Art in Eastern Europe 1968-1981, 81, 94–95, 140, 158, 305) Even so, artists’ social orientation, for all its overlap with professional activity, was positioned against the wholesale depredations of capitalistic valorization. That general position aligned these artists with the socialist principles of the GDR, even though, or perhaps especially when, those principles were frequently betrayed by officialdom.

To understand the significance of socialism for Wolf-Rehfeldt and her peers requires recognition of its status as an ongoing and contested project. Rather than dogma handed down from the nineteenth century and solely determined by the ruling Socialist Unity Party of Germany (SED), socialist ideals were constantly negotiated and debated as part of everyday life.(That is, of course, not to suggest that everyday experience was separated from the actions of the SED. Most infamously, the Ministry for State Security launched highly destructive and wide-ranging campaigns of repression against individuals and organizations. Even so, such a context shaped but did not entirely determine private and semi-public life. See Paul Betts, Within Walls: Private Life in the German Democratic Republic [Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2010]; Sara Blaylock, Parallel Public: Experimental Art in Late East Germany [Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2022]; Yvonne Fiedler, Kunst Im Korridor: Private Galerien in Der DDR Zwischen Autonomie Und Illegalität B[erlin: Ch. Links, 2013]) One of the most important aspects of these ideals was work, which was framed in terms of an individual’s meaningful engagement for their own self-development as well as their contribution to the development of a larger, social collective.(Franziska Becker, Ina Merkel, and Simone Tippach-Schneider, Das Kollektiv Bin Ich: Utopie Und Alltag in Der DDR [Köln: Böhlau, 2000], 7–8) Just as importantly, that conception of social collectivity extended beyond national boundaries. Owing in however minor a way to the mail artists’ activities, East Germany comprised a “lived web of interconnections among individuals, imbued with different meanings,” the ambiguities and overlaps of which constituted a collective “creative process.”(Ina Merkel, “The GDR—A Normal Country in the Centre of Europe,” in Power and Society in the GDR, 1961-1979: The “Normalisation of Rule”?, ed. Mary Fulbrook [New York and Oxford: Berghahn, 2009], 195. Although recent scholarship has done much to erode the stereotype of the GDR as a hermetically sealed redoubt, it must not discount earlier historical recognition of artistic and cultural exchanges across geopolitical lines. See, for example, Christoph Tannert, “Der Westen Im Osten [Und Umgekehrt?] – Berliner Künstler auf der Suche nach Dialogen,” in Interferenzen: Kunst aus Westberlin, 1960-1990, ed. Barbara Straka [Berlin: Verlag Dirk Nishen and NGBK, 1991], 146–47) Accordingly, Wolf-Rehfeldt described her pursuit of the typewritings and involvement in mail art as akin to a spider spinning a web.(Kornelia Röder et al., “Gespräch / Discussion,” in Mail Art: Osteuropa Im Internationalen Netzwerk, ed. Kornelia von Berswordt-Wallrabe [Schwerin: Staatliches Museum Schwerin, 1996], 133)

The socialist project was always in the making across borders and between people. Every To implied a From (1974). Wolf-Rehfeldt’s socialism “from below” was renewed through the lateral bonds of the mail art system, bonds that were distanced yet familiar. In this respect, she and her fellow artists acted in that wider socialist imaginary, one in which individuals were conscious participants in social development, and articulated these imaginaries through various forms of cultural production.(Seán Allan, Screening Art: Modernist Aesthetics and the Socialist Imaginary in East German Cinema [New York: Berghahn, 2019], 4–5) There was neither a necessary contradiction between individual practice and cooperative orientation, nor a conflict between their position in East Germany and an international outlook. Their distinction lay in the shared dedication to a socialist modernity based on international solidarity.

Traces of Social Crisis

Although a buoyant and growing market for mail art has since developed, the artists’ ethos of participation rejected calculus and quantification, and objected to the extraction of value and the externally imposed demands of production. Though by no means divorced from productivist impulses and relations of exchange value, the GDR remained important for Wolf-Rehfeldt, as was clear from the SOS and its warning of a coming “irreparable violation.” Although she did not wish to martyr herself, and stated as much in interviews, she nonetheless held on to socialist ideals throughout her life.(Röder et al., “Gespräch / Discussion,” 136) Over thirty years after the official embodiment of those ideals vanished, the significance and legacies of reunification remain fraught. The abrupt shift from actually existing socialism to increasingly neoliberal capitalism constituted Germany’s own version of shock therapy. The “brutal process” of economic restructuring and deindustrialization led to sharp increases in unemployment, and fueled outbreaks of xenophobic violence.(Jonathan R. Zatlin, “Getting Even: East German Economic Underperformance after Unification,” in United Germany: Debating Processes and Prospects, ed. Konrad H. Jarausch [New York and Oxford: Berghahn, 2013], 123) Austerity policies undercut social services, which further exacerbated the turmoil of transition.(Ned Richardson-Little, The Human Rights Dictatorship: Socialism, Global Solidarity and Revolution in East Germany [Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2020], 262–63) Unsurprisingly, given the historical forces at work, official narratives have instead largely celebrated the end of the GDR and positioned the Wende as a “joyful historical memory.”(Hope M. Harrison, After the Berlin Wall: Memory and the Making of the New Germany, 1989 to the Present [Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2019], 26; Frank Hörnigk, “Unity and Difference: Some Reflections on a Disparate Field,” in United Germany: Debating Processes and Prospects, ed. Konrad H. Jarausch [New York and Oxford: Berghahn, 2013], 205–12) The SOS issues a succinct challenge to such narratives. It offers a plea to retain “positive intrinsic values” that, while enmeshed in a system inarguably in dire need of deep political reforms, opposed the rampant commodification of social relations.

Equally, the SOS issues a call to arms that can be seen in response to both precedents in mail art and then recent developments in the GDR. The months leading up to the Mauerfall had seen a steady increase in civil demonstrations. Since September, rising numbers of citizens had been gathering and marching through Leipzig, Dresden and other cities to demand social and political changes. Along with leafleting campaigns and letters to newspapers, this groundswell of popular resistance to the regime culminated in large-scale demonstrations on Alexanderplatz in East Berlin on November 4, 1989. This event incorporated speeches from an irreconcilably wide range of figures in the spheres of culture and politics, from Markus Wolf, the head of foreign intelligence in the Ministry for State Security, to the novelist Christa Wolf and playwright Heiner Müller. The SOS thus appeared during a period of intense and very live set of debates over the future of the socialist project and the prospects of reunification.

At the same time, Wolf-Rehfeldt’s call for support connects localized movements to a wider international public. Her circulation of the leaflet mobilized the mail art network for political action, an act with its own historical precedents. At the end of September 1972, just as she had begun producing her typewritings, police in Buenos Aires closed an exhibition that had been curated by Jorge Glusberg, who was wanted along with the artists. “We all must help him,” implored artist Klaus Groh in response.(Klaus Groh, “Help!! Jorge Glusberg Is Wanted by the Argentinian Police” [International Artist’s Cooperation, October 2, 1972]. Emphasis in original) As president of the International Artist’s Cooperation network, he sought to rally widespread support. His distributed leaflet calls on recipients to send a telegram to Alejandro Agustín Lanusse, then president of the military junta in Argentina, requesting Glusberg’s release. In perhaps the most high-profile example from the decade, artist Geoffrey Cook organized a campaign to seek the release of mail artists Clemente Padín and Jorge Caraballo. In August 1977, authorities in Uruguay imprisoned them for protesting against the military dictatorship. The campaign led to their release and fomented international pressure on the Uruguayan government.(Geoffrey Cook, “The Padin/Caraballo Project,” in Correspondence Art: Source Book for the Network of International Postal Art Activity, ed. Michael Crane and Mary Stofflet [San Francisco: Contemporary Arts Press, 1984], 369–73) Through such acts, otherwise relatively localized events became an occasion for international solidarity.(Other examples from the decade include Action on Behalf of Milan Knížák [1973], which was a petition to the Czechoslovak Socialist Republic that called for the release of Milan Knížák, who had been sentenced to prison after providing works to the German collector Hans Sohm; petitions in support of Guillermo Deisler, who was imprisoned and exiled following the 1973 coup in Chile led by Augusto Pinochet; and Edgardo-Antonio Vigo’s circulated works that sought the release of his son Palomo Vigo, who had been kidnapped and “disappeared” by agents of the Argentine military dictatorship in 1976) A crucial point, however, differentiates Wolf-Rehfeldt’s activity. She did not canvas assistance for particular individuals; she sought to rally support in defense of a general system. “Ask your friends,” she requests, to aid in wider resistance to the absorption and abolition of the GDR. Rather than indulge in the spectacular triumphalism of the fall of the Wall, or invoke the cynical calculations of geopolitical wrangling, she appeals along far more intimate lines. At stake was nothing less than the ongoing claim to the future reinvention of the socialist project.

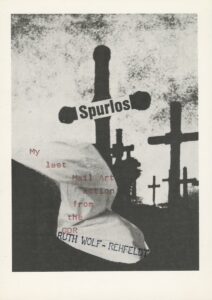

Ruth Wolf-Rehfeldt, Spurlos – My Last Mail Art Action from the GDR, 1990. Offset print, typewriting, rubberstamp, signed, 4 9/64 x 5 53/64 in. (10.5 x 14.8 cm). Artwork © Ruth Wolf-Rehfeldt. Courtesy of Museum of Fine Arts – Artpool Art Research Center, Budapest, 2024.

The wholesale political upheaval prompts reflection on artistic forms capable of mediating the dissolution of a distinct social form. Wolf-Rehfeldt’s dexterous response heads in two directions: trace and destruction, or, perhaps better put, the traces of destruction. The signs of that end can be seen in one of her final works: Spurlos. The distinctiveness of this work, which accompanied the SOS, lies in the manner in which she substitutes her typical arrangements of typewritten characters with depictive offset print.

Even at this late stage, Wolf-Rehfeldt continued to call for support. Dated February 27, 1990, just five days after the SOS, she once again appeals to the recipient on the verso. “I am asking for your help too,” she implores. On March 18, the GDR held the only free elections in the history of the country. These saw the center-right Alliance for Germany form the largest voting bloc, and were decisive for the rapid pace of reunification. Evidently, these developments spurred a number of artists, including Renate Paulsen, Joaquim Branco, Mogens Otto Nielsen, and Ursula Loeckx-Wiegard to reply to Wolf-Rehfeldt’s call for support. In a letter from New York dated March 28, for example, artist David Cole enumerated some of the “problems involved in rapidly becoming ‘western-capitalized,” from rampant consumerism and gendered exploitation to “ever-present racism” and environmental destruction.(David Cole, “[Untitled Letter to Ruth Wolf-Rehfeldt],” March 28, 1990, inv. no. 2870, Ruth Wolf-Rehfeldt Archives, ChertLüdde, Berlin)

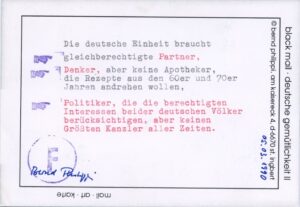

Bernd Philippi, deutsche gemütlichkeit, 1990. Black, blue and red ink on paper, 5 7/8 x 4 1/8 in. (15 x 10.5 cm). Artwork © Bernd Philippi. Courtesy of the artist and the Mail Art Archive of Ruth Wolf-Rehfeldt and Robert Rehfeldt, Berlin.

Other correspondents offered more sardonic reactions to the unfolding political situation. When fellow artist Bernd Philippi wrote to Wolf-Rehfeldt, he enclosed his own proposal typed on a postcard. Translated, his text reads: “German unity needs equal partners, thinkers, not pharmacists who want to push prescriptions from the 60s and 70s, politicians who take into account the legitimate interests of both German peoples, not the greatest chancellor of all time.” His mocking reference to Helmut Kohl, then chancellor of the FRG and leader of the conservative Christian Democratic Union, is indicative of the milieu in which Wolf-Rehfeldt operated. Seen in this light, SOS serves as a pendant to Spurlos, which, as Sarah James has argued, memorialized the “collapse of a dream which many people had cherished.”(James, Paper Revolutions: An Invisible Avant-Garde, 318) The somber tone of Spurlos, though, did not only apply to events outside the studio. In tandem with the rapid dismantling of the GDR, the choice of a graveyard declared the putative death and burial of her own practice.

The imminent imposition of a capitalist market economy prompted poignant and telling responses in Destruction and Destruction 2 (1990). The dynamic marked out by To and From does not conclude with nostalgic reverie, but in an internalized rupture at the levels of production and form.

Ruth Wolf-Rehfeldt, Destruction 2, 1990. Typewritten black ink on paper, collage on black cardboard, 11 7/32 x 14 11/64 in. (28.5 x 36 cm). Artwork © Ruth Wolf-Rehfeldt. Courtesy of the Centre for Artists’ Publications / Fonds Ruth Wolf-Rehfeldt. Weserburg Museum für moderne Kunst, Bremen.

Over the previous two decades, Wolf-Rehfeldt had made her typewritings through readily reproducible means and circulated them as carbon copies, screenprints, and zincographs. By the 1980s, she had also begun to make collages by pasting print media over her prints. The resultant pieces often punctured the commodified images of women frequently found in advertising.(James, 290, 293–97) Dispensing with depictive imagery for Destruction and Destruction 2, her arrangements visually recall Hans Arp’s papiers déchirés. Between the 1910s and 1930 he produced these collages of torn-and-pasted color paper by combining chance operations and manual manipulation.(On the importance of the aleatory for the conception and execution of Arp’s collages, see Eric Robertson, Arp: Painter, Poet, Sculptor [New Haven: Yale University Press, 2006], 44–50)

Jean Arp (Hans Arp), According to the Laws of Chance (Selon les lois du hasard), 1933. Sugar paper on plyboard, 159 × 173 mm (support). Tate, London. Used under fair use.

Wolf-Rehfeldt’s final collages crucially differed in terms of the material obliterated. To make the Destructionseries she dismembered her own prints to create the sets of irregularly sized, curvilinear shapes that she stuck down in radial arrangements. The pieces neither fit together nor add up to a new whole, however disjointed. That some torn-off pieces remained missing further reinforces the degradation of that prior work, which leaves only a partial trace.

The auto-destructive method, if not as dramatic as that promulgated by Gustav Metzger in the 1960s, is distinctive in the history of modern and contemporary collage. For more than a century, artists working in a range of international contexts—from Pablo Picasso and Hannah Höch in the 1910s through Wolf-Rehfeldt’s contemporaries Annemarie Balden-Wolff and Dieter Tucholke in the 1960s and 1970s to Lorna Simpson and Brook Andrew in the 2020s—have often sourced the visual material for collages from print media, especially magazines, newspapers, and periodicals.(For an overview of collage practices, see Patrick Elliott, Freya Gowrley, and Yuval Etgar, Cut and Paste: 400 Years of Collage [Edinburgh: National Galleries of Scotland, 2019]) In these various cases, artists cut, folded, and re-arranged imagery, a set of manual techniques that supplied collage with its double-coded, critical possibilities. These tactics registered, on the one hand, the extent to which the artwork was dependent on the shifting structures and fluctuating imperatives of the mass public sphere.(In the GDR, art historian and museum curator Roland März argued along similar lines. He maintained that collage, whether it comprised primarily depictive media or offered more abstracted compositions using layers of colored paper [as in the case of Renate Göritz], challenged viewers to reassess how images were constructed and related to social and material conditions. See Roland März, Die Collage in Der Kunst Der DDR [Berlin: Nationalgalerie, 1975]; Roland März, Collagen in Der Kunst Der DDR [Leipzig: Seemann, 1978]. For a more detailed survey, albeit lacking Wolf-Rehfeldt’s collages, see Heinrich Schierz and Reinhild Tetzlaff, eds., Die Kunst Der Collage in Der DDR, 1945-1990 [Cottbus: Staatliche Kunstsammlungen, 1990]) To fracture the visual field, on the other hand, marked out the distance of the artwork from that domain. Wolf-Rehfeldt severs such links by producing collages from her own prior work. The historical avant-garde provides some precedents for this maneuver. Arp assembled Torn-Up Woodcut (1920-54) from pieces of one of his Cologne Dada prints, whereas Höch made Collage II (Auf Filetgrund) (Collage II [On filet ground]) (1925) out of embroidery elements she had designed while working part-time work at Ullstein & Co.(On this work by Höch during an earlier period of social upheaval, see Max Boersma, “Global Patterns: Hannah Höch, Interwar Abstraction, and the Weimar Inflation Crisis,” Grey Room, no. 91 [2023]: 20–21) Wolf-Rehfeldt pushes this tactic to an extreme. The Destruction prints unleashed the dialectical logic of collage and set its rupturing impulse against the continuation of her practice per se.

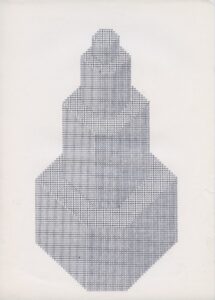

The resulting formal and material fragmentation registers the rapidly atomizing social sphere. The very signs of language that previously held together her compositions, and which perpetuated the cooperative project of mail art, negated their status as markers and makers of relations and became indices of disconnection. Close scrutiny of the Destruction collages indicates that Wolf-Rehfeldt had ripped apart some of her Turm prints produced during the 1970s and early 1980s, prints that had once again been produced for circulation through the mail art network.

Ruth Wolf-Rehfeldt, Turm, 1976. Original typewriting, 11 3/4 x 8 1/4 in. (29.7 x 21 cm). Artwork © Ruth Wolf-Rehfeldt. Courtesy of private collection.

Although Wolf-Rehfeldt produced different versions of these towers, they were all carefully planned and regularly composed. In short, they offered a vision of order constructed from the standardized marks of language. At the same time, their reproduction facilitated exchange beyond a market economy. Not only did reproduction undermine the traditional status of the unique work of art and enable wider distribution, most importantly of all it facilitated the distanced intimacy so important to these artists. By 1990, however, the imminent change of regime threatened to subsume all works under the aegis of the fungible. As a method, reproduction no longer lent the work a degree of distance from socio-political conditions, precipitating a shift towards the singular print. As though to reinforce that point, the prints comprise a set but remain unique, and so remain at some remove from the crucial techniques of commodification, reproduction and exchange. Just as the rule of the market was on the verge of becoming hegemonic, to reject its techniques seemed the most viable option.

Seen 35 years after the fall of the Wall, Wolf-Rehfeldt’s final works open a space for reassessing the triumphalist rhetoric and progressive claims that attended it, and for gauging the consequences for artistic practice. It remains necessary, as historian Jennifer Allen has argued, to critique the historiographic and political positioning of the Wende as the apogee of progressive development.(Jennifer L. Allen, “Against the 1989–1990 Ending Myth,” Central European History 52, no. 1 [2019]: 125–47) Seen in this light, Destruction and Destruction 2 give vivid form to the dislocations and possibilities of artistic practice during the period. The fragmentation of her collages put paid to the very notion of Einheit, especially one predicated on the ruination of prior social forms and that would proceed in the service of neoliberalism. By offering an extreme cultural position, Wolf-Rehfeldt’s practice, or rather the end of it, negatively implied a wider field of responses to the dissolution of East Germany, recognizing of course that its ends are ongoing.(Kerstin Brückweh, Clemens Villinger, and Kathrin Zöller, “Die Lange Geschichte der »Wende«,” in Die Lange Geschichte der »Wende«: Geschichtswissenschaft Im Dialog, ed. Kerstin Brückweh, Clemens Villinger, and Kathrin Zöller (Berlin: Ch. Links Verlag, 2020), 21–66. The ongoing process of reunification has also prompted greater recognition that the GDR was not just multifaceted, but that there were in effect many GDRs. See Christopher Banditt, Nadine Jenke, and Sophie Lange, “Die DDR Im Plural,” in DDR Im Plural: Ostdeutsche Vergangenheiten und ihre Gegenwart, ed. Christopher Banditt, Nadine Jenke, and Sophie Lange [Berlin: Metropol, 2023], 13–20)

When epochal political upheaval barred socialist futures, it imperiled too the open-ended project of mail art within the socialist imaginary. Crisis lay not so much in the overturning of a particular state formation as it existed in 1990, and certainly not in the dismantling of the repressive one-party apparatus. Rather, the Wende annulled the possibility of immanently reimagining actually existing socialism through acts of cultural production. That catastrophe entailed more than the destruction of Wolf-Rehfeldt’s prior work. Predicated on a form of social organization on the cusp of elimination, her mode of practice could only respond by negating its own past and future production. Shortly after declaring these prints and mail art actions from 1990 to be her last works, she stuck to her word. For more than two decades she all but disappeared from the art world. When crisis wrought a set of conditions inimical to practice, it was better to withdraw than to participate, to secede than to succumb. Yet, although the “social circumstances and rights” in the GDR have long since fallen into oblivion, and the public sphere in the FRG further fragments amidst a right-wing resurgence and deepening inequality, the social art of her typewritten pages endures as a model to be tested anew.

Part of this research was presented at the Culture and Catastrophe in Modern Europe workshop at the University of Chicago in March 2024. I wish to thank all participants for their generous feedback, especially Jennifer Allen, Alice Goff, Christoph Weber, and Jeremy Best. The editors at ARTMargins Online, particularly Sven Spieker and Raino Isto, provided incisive comments on a prior draft, as did Antje Paul. This article is dedicated to Ruth Wolf-Rehfeldt (1932-2024).