Broken Narrative: The Politics of Contemporary Art in Albania

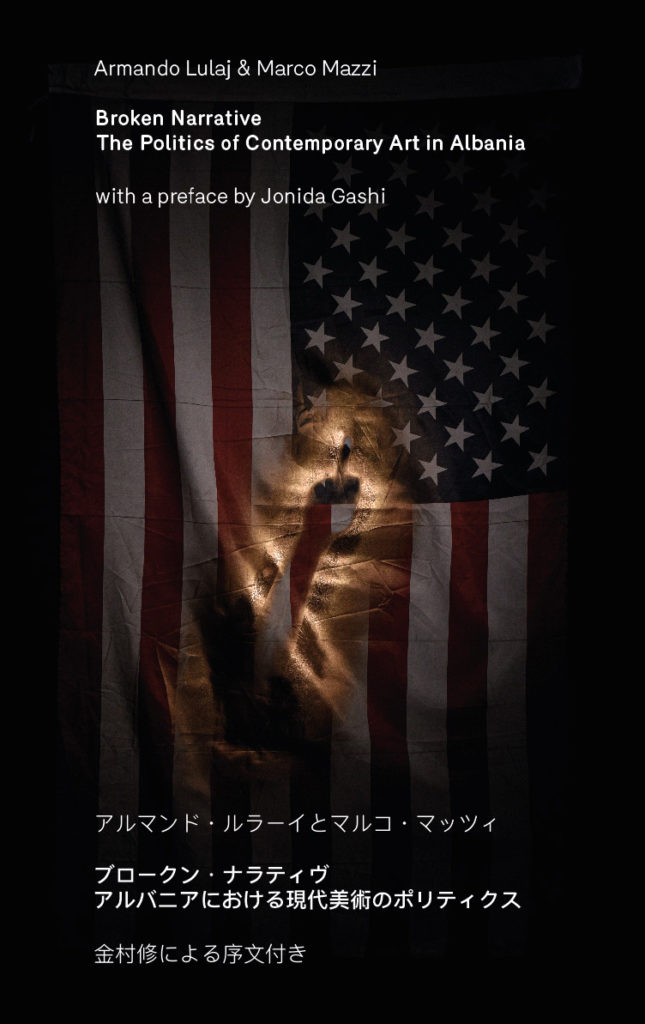

Armando Lulaj and Marco Mazzi, Broken Narrative: The Politics of Contemporary Art in Albania (Earth, Milky Way: Punctum Books, 2022), 364 pp.

Broken Narrative is a book from the margins peddling central, bringing recent Albanian history into conversation with central ideological currents of our times. This symbolic exchange between local and global stories unfolds through a dialogue between Italian-educated Albanian artist Armando Lulaj and Italian photographer and multi-media artist Marco Mazzi, presenting a microcosm of a long overdue Albanian-Italian conversation. Encapsulating some of Albania’s most persistent dreams and nightmares, Italy emerges as a simulacrum of sorts, an actual and imaginary political space in which Lulaj and Mazzi lay out a critique of neoliberal post-communist transition, its subtle and open violence(s), its body-politics, and the complicity of the artistic community in establishing new authoritarian regimes in the wake of transition. In conversation with Lulaj’s artwork, the reader is faced with the aftermath of the application of the Washington Consensus in the case of Albania: economic shock therapy, mass privatization, massive unemployment, mass immigration, mass drowning, mass murder, mass alienation, the ultimate fall of the state in 1997, and the anarchy that unfolded, permanently crushing any utopias that had dared to emerge in 1991 (when communism in the country ended). In addition, readers are introduced to the contemporary conundrum of Albanian society, which remains trapped between a growing tripartite political-artistic-criminal governance on the one hand, and the hard ideological currents of the country’s recent history on the other.

Broken Narrative comprises a transcription of an extended interview between Lulaj and Mazzi, spread across 5 untitled “tracks” (as the book refers to them, as opposed to “chapters”), translated in both English and Japanese. Lulaj’s responses to Mazzi’s questions were recorded at different moments within what the authors call “our contemporary penitentiaries.” (p. 24) The choice to merely number the tracks seems suitable, considering that—individually—they lack a coherent thematic structure. Rather, Mazzi attempts to structure the interview through Lulaj’s artwork, with tracks 3 and 5 focusing extensively on Breaking Stones (2017) and Control (2018) respectively. As Mazzi relates these works to Albania’s contemporary conditions, Lulaj is invited to dissect his work’s aesthetics and the political reality through overlapping themes. There is a chronological tendency, insofar as the book starts from the early transition and ends with the current state of control, but time—for Lulaj and Mazzi—seems to have a circular rather than linear quality.

Lulaj is an eclectic artist whose practice ranges from landscape interventions and video work to photography and institutional critique. Born in 1980, he represented Albania at the Venice Biennial in 2015, and has maintained a critical role in the contemporary art scene in the country through his involvement with the DebatikCenter of Contemporary Art, which he initially co-founded in 2003. In the book, Lulaj claims to be on a quest to capture the spirit of his own time—a calling he considers fundamental to any artist. Lulaj’s artwork and practice have a political quality to them—they are spurred by the margins of the political landscape and the perspective of the ordinary citizen, and take aim at the surveilling eye of the central government, its violent apparatuses, and the artistic façade that cements power in contemporary Albania. Symbolically, Lulaj’s artwork is embedded in Albania’s permanent state of exception, which is reinforced by just this alliance between artistic discourse and centralized state power (discussed further below). Lulaj’s works often aim to trace the implications of this condition, as in his work Bullet in Envelope (2018), discussed in track 4. The work included the tip of a bullet that had been fired and a letter that would be decipherable only under a police microscope, and it was produced in collaboration with the artist’s cat, named Marcel Duchamp, before being mailed (on November 29, the anniversary of Albania’s liberation from fascist forces) to the former director of Albania’s National Gallery of Art. Rather than being understood in terms of its art historical references, the work was—as Lulaj says—“denounced as a violent gesture against public morals because it used criminal language which, according to the verdict of artistic officialdom, cannot be considered art.” (p. 223) The work traces the degradation of art institutions in Albania into meaningless bureaucratic sites where a renewed practice of censorship refuses to acknowledge the possibility of any relationship between art and politics, or art and crime.

Lulaj is an eclectic artist whose practice ranges from landscape interventions and video work to photography and institutional critique. Born in 1980, he represented Albania at the Venice Biennial in 2015, and has maintained a critical role in the contemporary art scene in the country through his involvement with the DebatikCenter of Contemporary Art, which he initially co-founded in 2003. In the book, Lulaj claims to be on a quest to capture the spirit of his own time—a calling he considers fundamental to any artist. Lulaj’s artwork and practice have a political quality to them—they are spurred by the margins of the political landscape and the perspective of the ordinary citizen, and take aim at the surveilling eye of the central government, its violent apparatuses, and the artistic façade that cements power in contemporary Albania. Symbolically, Lulaj’s artwork is embedded in Albania’s permanent state of exception, which is reinforced by just this alliance between artistic discourse and centralized state power (discussed further below). Lulaj’s works often aim to trace the implications of this condition, as in his work Bullet in Envelope (2018), discussed in track 4. The work included the tip of a bullet that had been fired and a letter that would be decipherable only under a police microscope, and it was produced in collaboration with the artist’s cat, named Marcel Duchamp, before being mailed (on November 29, the anniversary of Albania’s liberation from fascist forces) to the former director of Albania’s National Gallery of Art. Rather than being understood in terms of its art historical references, the work was—as Lulaj says—“denounced as a violent gesture against public morals because it used criminal language which, according to the verdict of artistic officialdom, cannot be considered art.” (p. 223) The work traces the degradation of art institutions in Albania into meaningless bureaucratic sites where a renewed practice of censorship refuses to acknowledge the possibility of any relationship between art and politics, or art and crime.

Broken Narrative seeks to illuminate these connections, which neither the artworld nor political commentators in Albania seem willing to investigate in depth. The book begins with a discussion of 1997, the year of state collapse, anarchy, and civil war, and in choosing this starting point, the book refuses to provide any easy way out of the tense recent history of Albania’s post-communist transition. Albanians frequently refer to this notorious year by its bare name, 1997 (or simply ‘97), without explanations or subtitles: it is the year when their post-communist dreams of freedom and prosperity were violently shattered, and their life savings were lost to pyramid schemes that had been set up in the years following 1991. The anemic state was dismantled and anarchy erupted, thousands left and drowned in the Adriatic sea trying to reach Italy, organized crime reigned for those who remained in the country, and guns and grenades became ready available to children and adults alike. This long year resembled a civil war without clear sides—a Hobbesian war of all against all. 1997 is the year that shall not be spoken; as a profound trauma that affects Albania’s collective ability to remember, it’s also the year of the big amnesia. According to Lulaj, it is a year of blackout, with few memories compared to 1991. The epitome of transition, 1997 becomes a logical conclusion to Albania’s shock therapy of the early 90s.

Lulaj paints an even darker picture of what followed this first period of post-communist transition: a socialist government led by an artist Prime Minister that has trapped and transformed the country into some type of dystopia, which oscillates in between a surveillance and a disciplinary society. This artist politician is Edi Rama, the flamboyant former Mayor of Tirana, and son of the renowned communist-era sculptor and regime supporter, Kristaq Rama. Edi was trained as a painter and became involved early on in the student movements that resulted in the change of the regime. During his term as mayor in the early 2000s, Tirana got a makeover, with the most noticeable changes being the cleanup of the Lana riverbank and Rama’s project to colorfully paint the façades of numerous communist-era residential buildings in the city. His proclaimed success with Tirana as a pilot project during his mayorship was then upscaled in his bid to become Prime Minister in the 2010s; Rama christened his political campaign the “Renaissance” (Rilindja in Albanian), an immodest term suggesting both a “civilizational” project of bringing art and beauty to his supposedly backward citizens (an Orientalist lament central to his political discourse) and a rebirth or revival of the nation. Lulaj and Mazzi expect the reader to be familiar with this sociopolitical background, and their discussion proceeds directly to the grotesque nature of the “Renaissance” campaign.

During Rama’s term as mayor, an aggressive campaign of massive private constructions began that would forever transform the built heritage of Tirana. This campaign has been carried on by his successors, culminating with the current mayor, Erion Veliaj, and the infamous destruction of the historic National Theater building in central Tirana, on May 17, 2020. The destruction of the National Theater in the middle of a global pandemic, after months of resistance on the part of activists and artists, through special provisions passed under a state of emergency, to give way to private investors building skyscrapers, served as a wake-up call about the authoritarian tendencies of the national and local government in Albania. It also foregrounded a conundrum of private—often criminal—interests represented and protected by Albania’s elected officials. Here, we see the irony of the denunciation of a work like Bullet in Envelope as a criminal act.

In my reading, the book’s most original thesis emerges once we get to Rama’s terms as Prime Minister (an office he has held since 2013): in addition to the political, oligarchic, and criminal partnership found in many countries throughout Eastern Europe, in the case of Albania the contemporary art scene is part of the equation, serving power through its disciplining methods, censoring art through its aesthetic of decorum, and ultimately failing to bear witness to the agony of its society. The question of agency—as to whether the artistic elite is actively contributing to regime consolidation, or if the government operates through some form of instrumentalization of artists and the art scene—remains unresolved for the reader.

An additional thread running through the book is the impotence of Albania’s artistic community when it comes to reflecting or representing the state of its own society, a moral failure of epic proportions. Poets unable “to capture the image of their times” (p. 106), architects dismantling heritage and creating power-serving urban landscapes, art institutions becoming bureaucratic agencies that promote banal art, foreign curators paying lip service to the government, art events becoming government-led shows: these are some of the examples of this failure. Instead of bearing witness, the artistic community has been coopted and instrumentalized, turned into cogs in the official “Renaissance” narrative, which claims it is taking the nation and the art scene to new civilizational heights, into contemporaneity. This narrative, like every grand narrative, risks fallacies, false representation, fabrication of realities, and ultimately, the heightening of discipline and control. According to Lulaj, the price artists pay for their attraction to power is being subsumed into the top-down production of hegemonic narratives.

While Broken Narrative is right to emphasize the novelty of the unique governing alliances in contemporary Albania, the book overemphasizes the novelty of the subjugation practices of the artistic elite. While these methods of subjugation may be more sophisticated under current hybrid regimes in Eastern Europe, it is hard to ignore the legacy of communism, visible first in the art institutions themselves and the disciplinary practices of the artistic elite, and secondly in the practice of self-censorship, the drive towards civility, and the propriety of official art. Lulaj is not so naïve as to paint a rosy picture of art under the communist dictatorship—in fact, he blames the artistic elite for having failed to capture and process the violence of this past regime—but he nevertheless seems to allude to a better artistic period, a time that seems to reside during socialist realism. One wonders if that place and time of flourishing independent art in the history of Albania is instead a kind of Neverland.

Moving from the temporal dimension into the spatial one, there is another novelty that the book overemphasizes, this time regarding Albania and the rest of the post-communist space. Seen from a political science perspective, the coupling of neoliberal market transition and liberal democracy often failed to produce functioning states, strong democracies, fair economies, or thriving societies. More often than not, like Albania, post-communist countries established hybrid regimes, experienced democratic backsliding, or have faced new waves of authoritarian politics, or war, while finding their societies subjugated to an illegitimate monopoly on violence comprised of a melange of official state structures, private police, and organized crime—or else no monopoly on violence at all. In fact, so similar were some of the shared post-communist experiences in Eastern Europe and the former Soviet Union, that the sentiment expressed by Lulaj (in blaming the Western-blessed pacted elite transitions of the early 90s for what followed) is hardly unique. Some of the new authoritarian turns in Hungary, Poland, Russia, just to name a few, were predicated on the same political sentiments that blamed the dirty transitional elite pacts for saving the communist elite from persecution, enriched the corrupt new elites, impoverished the nation, and promoted non-benevolent Western interests, personified by George Soros as one of the easiest targets. Soros becoming a political target is not accidental insofar as the Open Society Foundation he founded plays a complex role in civil society support in the region, with a well-documented role in the elite exchanges that emulated colored revolutions from one country to the next in Eastern Europe.(See, for instance, Mark R. Beissinger, “Structure and Example in Modular Political Phenomena: The Diffusion of the Bulldozer/Rose/Orange/Tulip Revolutions,” Perspectives on Politics 5:2 (2007): pp. 259-276.) Ultimately, then, many aspects of the Albanian contemporary art condition that the book identifies (in terms of political conditions) actually make a case for the wider applicability of thinking through the Albanian case in a comparative perspective, when analyzing post-communist societies.

The unique character of Lulaj’s nostalgia in the book should be pointed out. He defines it as a nostalgia for what could have been, for the paths not taken, for the stolen futures, a nostalgia for times of hopes and dreams, often situated at the crux of major political change. While this form of nostalgia may recall Svetlana Boym’s category of reflective nostalgia,(Svetlana Boym, The Future of Nostalgia (New York: Basic Books, 2001).) Lulaj’s seems to be more actionable: it is a nostalgia filled with rage, with impending political action, with demands for the lost hopes of a society that lost everything following promises of prosperity, freedom, and a better life. It is in this sense that Italy, mentioned at the outset of this review, permeates the narrative as both a broken promise and a country at the center of Albania’s love-and-hate relationship with the West. Italy is a former invading power with colonial tendencies towards Albania. (Fascist Italy officially occupied Albania in 1939, after years of effort at colonial expansion in the country). And yet for Albanians it also represents the fountain of cultural and artistic inspiration, where part of Albania’s elite has historically (and currently) been educated, the country from which radio waves were secretly captured just to listen to the Sanremo Music Festival during communism. It is also a country that received a significant portion of Albania’s refugees and immigrants, and a country that left a ship full of Albanian refugees to drown in the Adriatic in 1997, under circumstances unclear to this day. In 2015, Lulaj took the skeleton of a sperm whale from Albania across the Adriatic to the Venice Biennale, a present from the sea they share.

In its few short “tracks,” Broken Narrative manages to analyze Albania’s modern society by touching upon the major themes of Foucault’s political philosophy (though without mentioning him): governmentality, discipline, the penitentiary, sexuality, criminality, madness, panopticism, and surveillance are all discussed. To these concepts, the Albanian case adds that of the contemporary art institution. It should come as no surprise, Lulaj claims, that the artistic lyceum in Tirana and one of the city’s penitentiaries (prison 313) share the same name: “Jordan Misja.”(Jordan Misja was an anti-fascist activist and a member of the Communist Party of Albania, killed by the quisling regime in 1942.) Lulaj builds upon this fact to point to the wider merger of the artist, the criminal, and the politician: “politics, organized crime, and contemporary art are governing a state.” (p. 159) One problem with Broken Narrative is that, similar to Foucault’s analysis, the book sometimes also leaves the reader without a sense of agency, and provides vague pathways to resistance. There is, however, one exception that serves as a moment of inspiration: the student protests that started in Tirana in 2018. For Lulaj, this was the only moment of real opposition to Rama’s regime. Through the urgency of its language, the book demands mobilization and revolt, like the actions of students in Tirana.

Broken Narrative: Politics of Contemporary Art in Albania seems almost an impossible book. It aims to provide a sober picture of transition and the regimes that spring up in its aftermath, and a catalogue of the most pressing issues faced in the country, while also advocating for the necessity of narrative plurality in spaces where narratives are monopolized. One rarely sees an analysis of such a plethora of themes in a single narrow place, in part because they can hardly be thoroughly analyzed in a single book. But thoroughness is not what this book is after—rather, it aims to shock, enrage, mobilize. It has no time to convince or to call on reason—one has to feel the heavy reality to critically engage with it, and this feeling seems to be Lulaj and Mazzi’s primary goal. Broken Narrative delivers what it proposes as a fundamental responsibility of the artistic community: “to sum up the present” (p. 166) —a kind of meta-representation of the times we are living, conceived from a space of plurality. The detailed overview also owes to the conversational style of the book, which allows the authors to dive into the multiple themes of the chaotic reality of transition. In my view, the book’s approach is more expansive than superficial, allowing readers to grasp the full and complex spectrum of factors conditioning art production in Albania—and the former socialist world—today.