“Being Together”: the Meeting of Mail-Artists at the F-Art Festival in Gdańsk, 1975

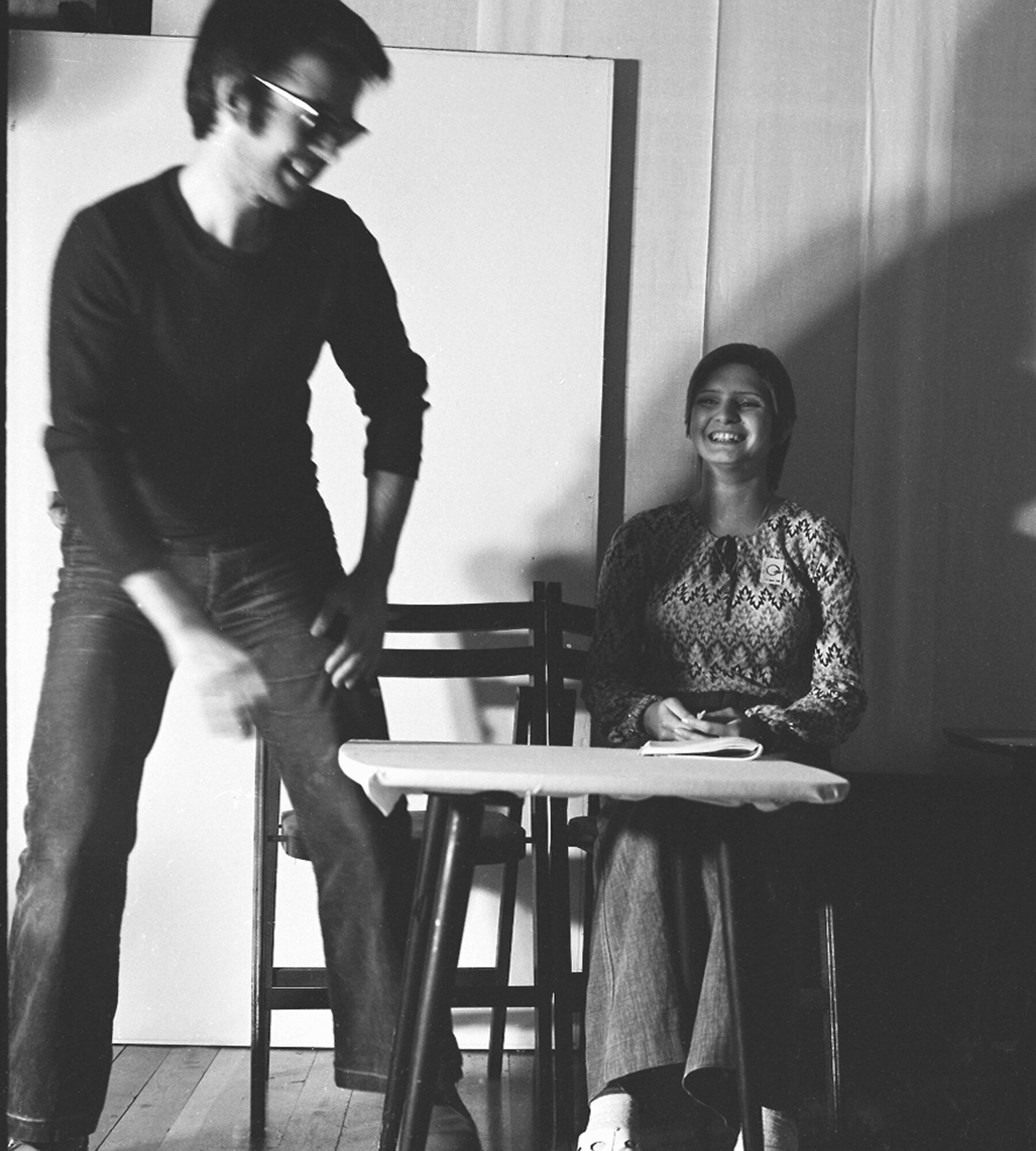

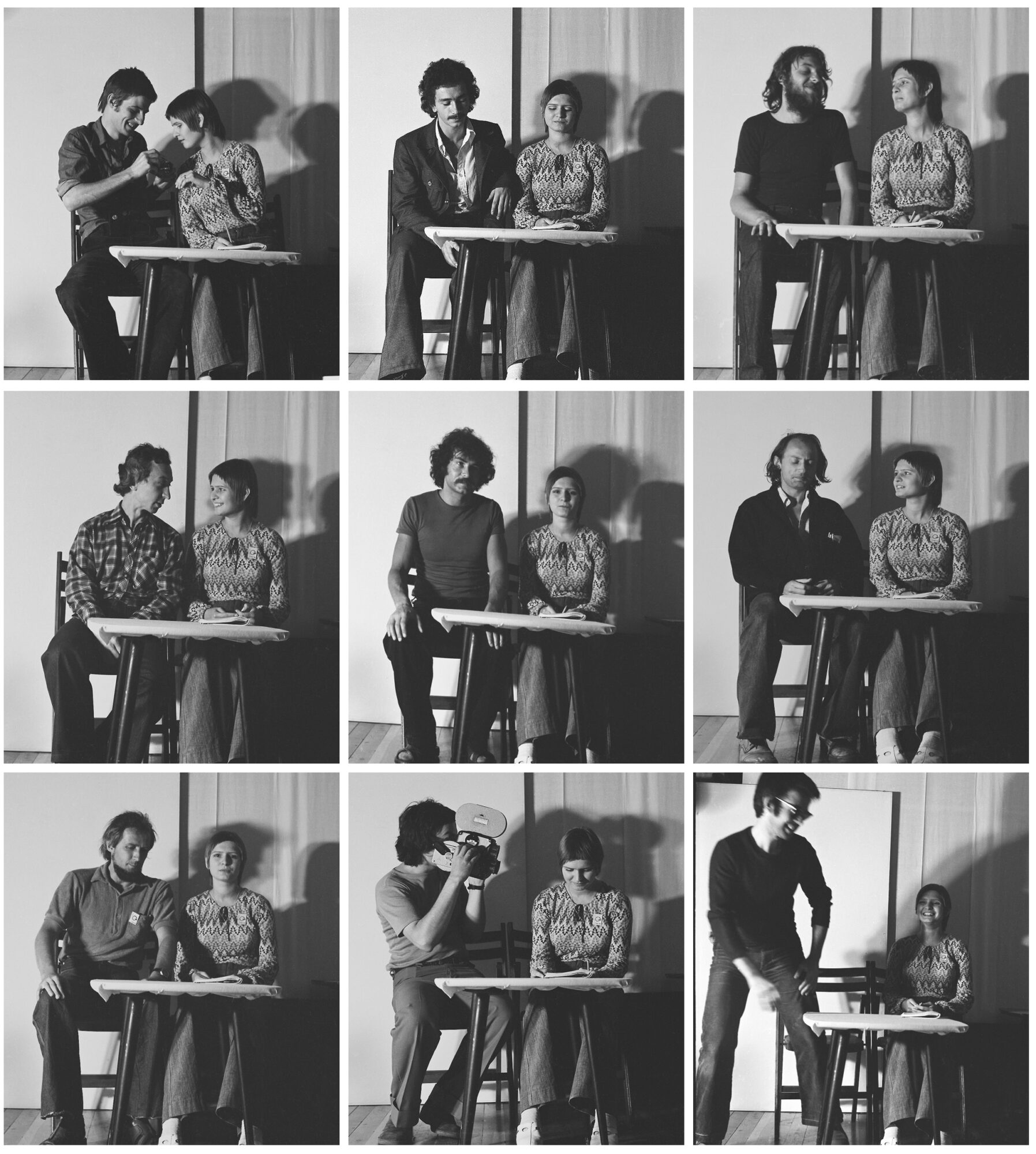

Anna Kutera. Presentation (detail), Anna Kutera with Niels Lomholt, 1975. Black and white photograph, dimensions variable. F-Art Festival, Gdańsk. Image courtesy of the artist.

1975 marked the changing field of neo-avant-garde practice in Poland in which a popularization and consolidation of the mail art scene brought to the fore the significance of networked art, particularly in its capacity to foster international exchanges and meetings. In the first half of the decade contact became an important feature of conceptual art and neo-avant-garde art in the region, both as a subject of art and as a practice. The following analysis of artistic events and undertakings in 1975 proposes this year as a watershed moment in the development of networked art in the region and re-thinking how Polish “avant-garde” artists positioned themselves within society in general. The term avant-garde is used rather broadly here, as the debate within the artistic milieu that was triggered by Wiesław Borowski’s article on “pseudo-avant-garde” in 1975 revealed conflicting approaches towards who and what should be labeled avant-gardist.(Borowski Wiesław, “Pseudo-Awangarda,” Kultura, no. 12 (1975), pp. 2–7.) This essay focuses on the transformations of the role and function of networked art as exemplified by the F-Art festival in Gdańsk in September 1975. It highlights the increase in sociability and recognition of the importance of the local contexts manifested in artistic actions realized in transregional exchanges. The privileging of intimacy, familiarity, and knowledge of regional specificity marks a shift from the earlier networking ambitions of amassing a significant number of connections towards an approach that investigated the closeness and permanence of such contacts in the middle of the decade.

The biennials set up in Poland in the 1960s (such as the International Drawing Triennial in Wrocław, established in 1965, or International Biennial of Graphic Arts in Kraków, established in 1966) as well as plenairs—international art symposia—provided important, albeit limited, opportunities to encounter foreign artists. In the 1970s, however, it was the informal artistic networks, and particularly mail art, that allowed a number of Polish neo-avant-garde artists to reach, get to know, and exchange art with artists not only from the region but also beyond the Iron Curtain. I employ here a broad definition of mail art understood as art sent and exchanged between the artists through post. In my analysis of the F-Art festival, I focus on the transformation of artistic strategies and networking ambitions, as well as the various manifestations of contact in the neo-avant-garde practices. What emerges here is a proposition of the aesthetics of contact informed by the networking endeavors and artistic infrastructures.

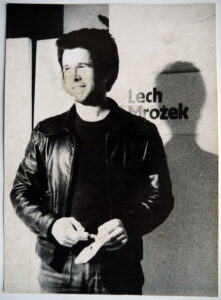

Lech Mrożek at F-Art Festival, Gdańsk, 1975, black and white photograph, 18 x 24 cms. Image courtesy of Lomholt Mail Art Archive. Photography by Niel Lomholt.

Lech Mrożek at F-Art Festival, Gdańsk, 1975, black and white photograph, 18 x 24 cms. Image courtesy of Lomholt Mail Art Archive. Photography by Niel Lomholt.

In 1975 a number of mail art exhibitions were held at publicly accessible galleries such as Art in Contact at Galeria Studio in Warsaw and Info: Art in Contact is Life in Art at Galeria Labirynt in Lublin—a departure from the use of private apartments and smaller artist-run initiatives for mail art exhibitions in the early 1970s—broadened the audience of the networked art while asserting its presence and confirming the authorities’ sanction.

At the same time, the increase in the number of international artists visiting the country significantly overlaps with their participation in the mail art network in terms of receiving invitations to exhibitions and events. Such overlap highlights the interconnectedness of networking and organizing endeavors and individuals’ multifaceted activities that co-created infrastructures of artistic exchange. The F-Art festival is a case study for the analysis of how artists responded to the notions of contact, communication, and togetherness while visiting a country they had usually only reached via post. It exemplifies an overlap of networking strategies and personal meetings at the time when efficient infrastructures of artistic exchange have already been operational in initiating connections. This is not to say that such international meetings had not happened before but to highlight the transformation of individual tactics of forging connections. The F-Art festival—organized by a student body—marks a generational change when artists who got involved with conceptual art and Eastern European contacts in the early 1970s, such as Andrzej Partum (b. 1938) and Endre Tót (b. 1937) started to interact with slightly younger participants, such as Anna Kutera (b. 1952) or Lech Mrożek (b. 1953). F-Art festival also signified a shift from the earlier conceptual approaches of networked art to a new understanding of the relations between art, contact, and locality initiated by Jan Świdziński’s theory of contextual art that signified a shift from the earlier conceptual approaches of networked art that postulated international communication.

Endre Tót typing with Andrzej Partum and Piotr Olszański, F-Art Festival, Gdańsk, 1975. Image courtesy of Lomholt Mail Art Archive. Photograph by Niels Lomholt.

“The symposium of Recent Art F-Art” (also referred to as the F-Art Counterculture Festival or as the Festival of Students from Baltic Art Schools) held in Gdańsk in 1975 was officially organized by the Academic Council of the Socialist Union of Polish Students of the Fine Arts Academy in Gdańsk (RU SZSP PWSSP)(Rada Uczelniana Socjalistycznego Związku Studentów Polskich Państwowej Wyższej Szkoły Sztuk Plastycznych.) with Romuald Kutera, Lech Mrożek and Piotr Olszański acting as its commissioners. Essentially a student festival, F-Art nevertheless gathered several international and Polish artists, including Ewa Partum, Anna Kutera, Endre Tót (from Hungary), Jan Świdziński, Andrzej Partum, Goran Trbuljak (from Yugoslavia), Jean Sellem (from Sweden), Aleksander Oczko, and Niels Lomholt (from Denmark). Artists’ presentations took varying forms: for instance, along with her own works, Ewa Partum exhibited, as part of the documentation of her Łódź Address Gallery, Maurice Roquet’s Being Together, which was shown there in the previous year. The ten-day-long symposium was filled with discussions, performances, and exhibitions as well as parties and a vivid social life spent on the Baltic beach. Although a number of the participating artists were involved in various degrees with mail art, the festival itself was not directly devoted to the practice.

As the artistic exchanges and personal meetings intensified in the first half of the decade coincided with a relative easing of international relations with Western Europe and beyond. The first few years of Edward Gierek’s rule were characterized by a new openness to the West and an increase in the standard of living. Huge loans obtained from the West enabled the import of consumer goods and an increase in national spending on them. Gierek, who spent part of his youth in France and Belgium and advocated the importance of maintaining political contacts outside the Iron Curtain, was enthusiastically welcomed in the West. On the other hand, Gierek’s policies were heavily dependent on the USSR; on February 10, 1976, the Polish constitution was amended, declaring Poland a socialist country with the Party as its leading force, and including a statement of “eternal friendship with the USSR.” Nevertheless, the sense of geopolitical and artistic isolation of the late 1960s—when select international events and activities were attended by a relatively small and group of artists—has been to an extent overcome both by the political change of government as well as artists’ endeavors, undermining a simplistic view of the one-sided permeability of the iron curtain and the eager receptivity of the Eastern side. The F-Art festival itself provides a case in point: at least in its conception it gathered the artists from around the Baltic Sea, proposing a delineation of a different understanding of proximity and regionality.

Nominally, F-Art was to gather art school students from the countries connected through the Baltic Sea, thus proposing an understanding of a region—or trans-regionality—based on geo-hydrological categories, rather than political ones. In practice, however, the absence of artists from East Germany and the Baltic States then part of the USSR and participation of artists from Hungary and Yugoslavia meant that both the cultural policies and already existing artistic connections resisted such transregional reconfiguration of connectedness. On the other hand, the trans-Baltic collaboration was welcomed by participants from the northern states, who, like Jean Sellem—at the time working in Lund in Sweden—were eager to continue artistic collaboration beyond the festival. An account offered by Niels Lomholt, a Danish artist and photographer, who in the early seventies incorporated his conceptual land art into the postcard format, offers an account of his involvement with the mail art network after the F-Art festival.

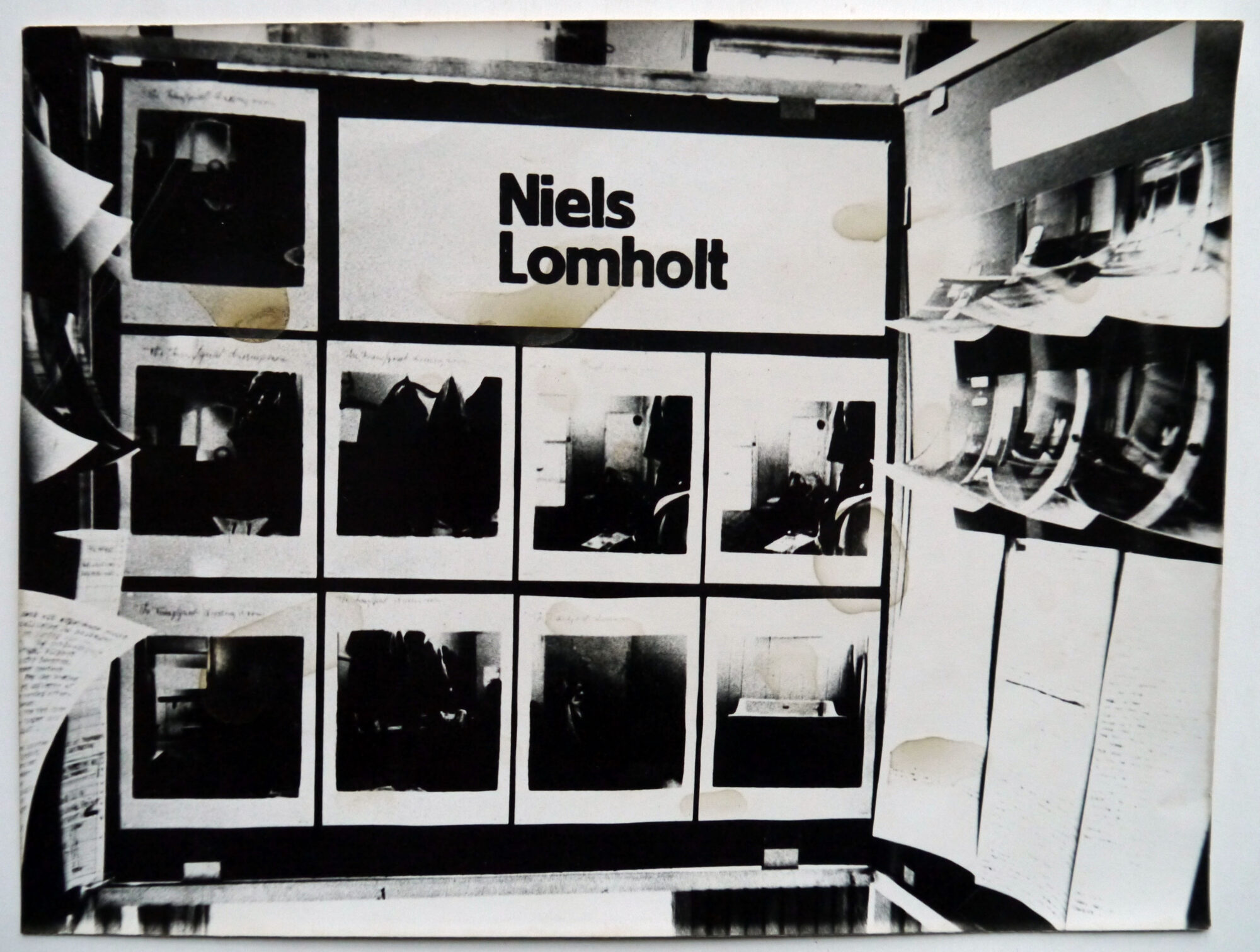

Niels Lomholt’s exhibition at F-Art, Gdańsk, 1975, black and white photograph, 18 x 24 cms. Image courtesy of Lomholt Mail Art Archive. Photograph by Niel Lomholt.

My first big leap in the Mail Art Network, apart from the daily practice of Mail Art, came in 1975, with an invitation to participate in an artists’ meeting in Gdańsk, Poland. I had been working on a project around the boxer’s dressing room: “The Trans-Quiet Dressing Room,” documentary photos, texts and a number of artworks. I took this project to Gdańsk. A number of East-European artists were present […]. The East European approach to art was astonishing, a presence to the bare bones. Their work was very conceptual, just a little more human, reflecting their social and political situation. It was time to find a personal way in and out of Mail Art.(Niels Lomholt, “In and Out of Mail Art,” Lomholt Mail Art Archive, http://www.lomholtmailartarchive.dk/texts/niels-lomholt-in-and-out-of-mail-art.)

Lomholt’s account, with all its awe and enthusiasm, to some extent reflects an often-repeated preconception about the particular characteristics of all Eastern European artists, homogenizing the region and characterizing certain nations and states through their position on the other side of the Iron Curtain. Later in his essay Lomholt recalls—with a degree of fascination and naivety—the rather spartan living conditions, such as disconnected urinals and lots of concrete, which “nobody cared about” as social life was thriving.(Lomholt, “In and Out.”) Nevertheless, it was this fascination that convinced the artist to start his Lomholt Formular Press, a participatory mail art project run between 1975 and 1985, the foundation of which “was laid on the challenge from social and physical order, hope, lust, and deliverance.”(Lomholt, “In and Out.”) Lomholt’s involvement in mail art not only coincides with the popularization of the practice in Poland as well as abroad, but also reverses the more frequent—East-to-West—direction of fascination and desire for contact. The emphasis on humanity, presence and reflection on social and political context was not solely an orientalizing gaze, but also reflected the particular conditions of artistic production that relied on exchange and cooperation, as well as on direct, persistent involvement.

The foundation of mail art galleries in Poland occurred almost simultaneously with Jarosław Kozłowski’s NET Manifesto from 1971, which marked not only the beginning of Polish, but more broadly Eastern European networked art.(Kornelia Berswordt-Wallrabe et al, Mail art: Osteuropa im internationalen Netzwerk [Eastern Europe in the International Network] (Schwerin: Staatliches Museum Schwerin, 1996), exhibition catalog.) Indeed, the term “mail art gallery” is itself problematic. In a correspondence art sourcebook published in 1984, the American curator and writer Judith Hoffberg stated that a “mail art gallery” is a contradiction in terms as well as in fact.(Judith A Hoffberg, “Mail Art Today: Self-Sustaining or Self-Destructing?” in Correspondence Art: Source Book for the Network of International Postal Art Activity, ed. Michael Crane and Mary Stofflet, (San Francisco: Contemporary Arts Press, 1984), p. xx.) Hoffberg criticized the replication of a typically institutional exhibition style that since 1976 has become increasingly similar to museum practices. She viewed this process as a betrayal of the values and ambitions of mail art, which sought to avoid and surpass institutions. The reason I find her comments important for the recognition of the galleries created during the emergence of the network in the European socialist states is precisely the discordance between the understanding of the institutional and political contexts of mail art in the two regions. Whereas criticism of consumerism and anti-institutional sentiments were frequently voiced by mail artists from the West, in Eastern Europe their initial aim was to overcome the isolation dictated by the political situation. In Poland, mail art galleries—with their formalized bureaucratic manifestations and pretense of transparency, performed largely for the benefit of the authorities—occupied spaces such as noticeboards, broom closets or single-room flats and made the development of the network possible by sharing contacts and information. As such, artist-run mail art galleries in Poland escaped the anti- and institutional binary as they served multiple roles while having to negotiate particular demands presented by the political system they were operating in.

In parallel, most of the first Eastern European artists involved in mail art approached the network as a tool and a space to present their work and learn about art created abroad rather than the genre itself. The first theorization and presentation of mail art in an official institutional context was offered by the French writer and curator Jean-Marc Poinsot in 1971 during the seventh Biennale de Paris.(Jean-Marc Poinsot, Mail Art: Communication á distance, concept (Paris: CEDIC, 1971).) Introducing the section devoted to postal art, Poinsot described mail art as primarily anti-consumerist, and defined it through its conscious engagement with exchange systems in general and the postal system in particular. Although an awareness of the inner workings of the mechanisms of postal circulation—and particularly censorship—was included in some of the exhibited works by artists from Eastern Europe, they more often sent various manifestations of their broader artistic practices and pieces that could simply fit into a regular envelope. Unlike the anti-consumerist and anti-institutional paradigm of Western mail art, it was predominantly the desire to present their art abroad and access information about international art that was the central motivation of early Polish mail artists.

In 1973, two years prior to F-Art, Romuald and Anna Kutera created the International Recent Art Gallery, which operated from the Kuteras’ private apartment in Wrocław and focused on mail art and exchanging information and works of art by post. Since 1972 Jan Chwałczyk’s Gallery of Creative Information—a noticeboard in the club of the artists union onto which he pinned all the artistic correspondence he received—had already been operating in Wrocław and sharing its contacts. The International Gallery of Recent Art did not hold any exhibitions in the flat, but Romuald Kutera initiated two actions under the gallery’s name—Sweeping (Zamiatanie) in 1973, during which the artists swept the streets to mock the artistic pretense of deserving special treatment and privileges, and Publication (Publikacja) from 1973 that presented the artists connected with the gallery.(Anna Markowska, “This Glass Must be Wiped Clean,” in The Recent Art Gallery, ed. Anna Markowska (Wrocław: Wroclaw Contemporary Museum, 2014), p. 26.) The official-sounding title given to the artists’ networking activities not only provided a protective veil of formality against the state’s surveillance of private international contacts, but also reflected the artists’ ambition to create an international art center. Romuald Kutera recalled that he was inspired by correspondence from Hungarian art theorist and mail artist László Beke, who urged artists to send him works in order to secure their international recognition despite the fact that he stored the works received in a cupboard in a tiny room in Budapest.(Romuald Kutera, “Fotografia, film I wideo-wspomnienia z lat 70” in Fotografia we Wrocławiu 1945-1997, ed. Sobota Adam (Wrocław: ZPAF, 1997), p. 58.)

Some months later an actual gallery was set up by Romuald Kutera, Lech Mrożek, and Lech Olszański in the Pałacyk Academic Culture Centre in Wrocław and was named Recent Art Gallery (GSN) after the earlier mail art gallery run by the Kuteras in 1973 and aligned with the Symposium of Recent Art (Sympozjum Sztuki Najnowszej) organized at F-Art festival. In her thorough analysis of GSN presented in a monographic publication The Recent Art Gallery Polish art historian Anna Markowska notes that accounts of the date of the creation of the Recent Art Gallery vary from 1974 to 1975, as well as those of who were the initial founders.(Anna Markowska, ed., The Recent Art Gallery, (Wrocław: Wroclaw Contemporary Museum, 2014). The publication accompanied the exhibition The Avant-Garde Did Not Applaud held in Wrocław Contemporary Museum October 10–December 8, 2014 and curated by Sylwia Serafinowicz and Piotr Stasiowski.) Romuald Kutera emphasized the initial collective work and plans to open the gallery, whereas Mrożek and Olszański pinpointed the opening of the space in Pałacyk as the beginning of GSN.(Anna Markowska, “This Glass Must be Wiped Clean,” p. 27.) GSN continued the Kuteras’ ambitions of fostering international exchanges, as well as drawing from the contacts and experiences of the organization of the F-Art festival in 1975. While exemplifying a change in paradigm of international artistic cooperation that increasingly relied on personal meetings and transnational visits, the festival in Gdańsk informed the development of the gallery’s program and future international collaborations.

Anna Kutera. Presentation, 1975. Black and white photograph, dimensions variable. F-Art Festival, Gdańsk. Image courtesy of the artist.

Anna Kutera’s performance Introduction (Prezentacja) presented at F-Art from the series Simulated Situations dealt with the subject of contact and communication in a humoristic yet intimate manner. Kutera invited nine male artists participating in the festival one by one to sit next to her in silence with each of the interactions lasting around one minute. Kutera initiated the action with a statement: “I am happy to be together with a group who understands the meaning of being together in art and getting to know each other without words.” Ewa Tatar stated that the performance was “a very difficult emotional situation of intimacy;”(Ewa Tatar, “The introduction—performance by Anna Kutera,” Parallel Chronologies: An Archive of East European Exhibitions, 2012, https://tranzit.org/exhibitionarchive/ewa-malgorzata-tatar-is-wyspa-anna-kutera-the-introduction/.) however, Anna Kutera indicated a slightly different interpretation of the situation. The artist recalled that “the moment he [an artist she invited to join her] sat next to me everyone was taking photographs and we were presenting ourselves but without words—it was reminiscent of posing for a press picture with this one and then with the other one.”(Ewa Tatar, “Zdarzyło się we Wrocławiu; an interview with Anna Kutera and Romuald Kutera,” September 16, 2008, Obieg, http://archiwum-obieg.u-jazdowski.pl/rozmowy/4421.) This statement hints at a possible mistranslation of the performance’s title, as the word presentation might be more fitting. Unlike that of Endre Tót, another participant of the festival, Kutera’s happiness at being together is not ironic. Rather, it explores the possibility of personal interaction without resort to language, while exposing the performative dimension of artistic contact. Kutera’s action with its emphasis on posing and being photographed and filmed—the ten-minute-long video was presented the next year in Sweden in the Contextual Art exhibition in Lund—tackles the issue of the politics of connectedness as a manifestation of an artist’s position within the increasingly networked field.

Opportunities to create both national and international artistic events were often intrinsically linked with acquaintances, and Kutera’s example is no different. Jean Sellem, a French artist living in Sweden, where he ran an experimental contemporary art gallery, St. Petri, in Lund, participated in the festival upon the invitation of Recent Art Gallery and invited Kutera to exhibit her works displayed at F-Art. In addition to her performance, Kutera showed her series The Morphology of New Reality, which consisted of photographs taken of the artist’s seven-year-old nephew presenting various stages and perspectives of various activities, such as sitting behind a table or holding a flower. The catalog for her 1975 exhibition in St. Petri stated: The apparent stasis underlines essential, though minimal changes of relations between the presented elements, which participate in organizing the new reality.(Anna Kutera, The Morphology of New Reality, November 29–December 10, 1975, (Lund: St Petri, 1975), exhibition catalog.)

Kutera’s exhibition in Lund turned out to be a breakthrough not only for the then twenty-two-year-old artist, but for her entire social milieu. Romuald Kutera recalls how he encouraged the artist and theorist Jan Świdziński to go to Sweden with Anna in order to discuss in person the possibility “of a large Polish avant-garde exhibition.”(Ewa Tatar, “Zdarzyło się we Wrocławiu.”) Świdziński started to write his theory of contextual art during the F-Art festival and had finished it before going to Lund in November 1975, where it was well received and led to the eponymous exhibition and publication in 1976. This chain of connections, seemingly reliant on a series of coincidental meetings and unforeseeable chances, was further extended over time, and led to the recognition of Świdziński’s concepts abroad. Sellem’s friend, Amerigo Marras who run the Centre for Experimental Art and Communication in Toronto read Świdziński’s text published in Lund and invited the author to the Contextual Art Conference organized in the same year, where he discussed his theory with a number of prominent local and international artists including Joseph Kosuth. Although these international encounters might appear to be lucky accidents, in fact they were the results of efforts over half a decade on the part of the artists of Recent Art Gallery to foster transregional and international contacts and maintain a presence abroad. Świdziński’s Contextual Art marks a shift from conceptualism towards an art theory that undermines the exploration of linguistic universalism in favor of the importance of immediate context. As the ninth point of the “12 Thesis of Contextual Art” published in 1976 states: “art as contextual art is concerned with the relation itself,” though it rejected relativism insisting that only one meaning is true in the given pragmatic context.(Jan Świdziński, “12 Thesis of the Contextual Art,” in “Kontekst/Kontekstualizm,” ed. Izabela Kowalczyk, special issue, Zeszyty Artystyczne 32, no. 1, (2018): pp 209–211.) Świdziński’s privileging of locality and particular social practice in his art theory, which was announced in Sweden in 1975 and then internationally presented and popularized, reflects the tension between local impact and international recognition, as well as a renewed interest in the immediate and specific social context. The incorporation of a contextualist perspective into networking practices marks a shift from earlier theorizations of networked art as exemplified by the NET manifesto. Kozłowski’s and Kostołwoski’s 1971 proposal highlighted potentially unlimited reach and assumed intelligibility of artworks amongst the participants of the network, an assumption that coincided with the popularization of conceptualist strategies of dematerialization, critique of objecthood, as well as linguistic analysis.

One of the pioneers of conceptual and feminist art in the region, Ewa Partum, explored affective elements/aspects within the network, not only in her visual poetry and actions, but also through the organizational labor connected with the Address Gallery she ran. Ewa Partum’s personal connections and her capacity to produce prints and catalogs for the artists she exhibited—which she owed to an acquaintance working at a printing house—helped to introduce international artists to Polish audiences. A publication accompanying Maurice Roquet’s exhibition at the Address Gallery in June-July 1974 entitled Étre Ensemble (Being Together) introduces his project capturing various types of contact between people. The Belgian artist registers these “signs demanding a physical presence of people who share some sort of relationship” and describes them as a spectacle that serves to “represent a connection and inform about the existence of a particular relation between the actors.” A detailed analysis accompanying a photograph of two people holding hands assumes an objective, distant and scientific position, and explains the relationship between the couple, regarded by Roquet as actors performing a scene. Roquet questions how manifestations of relationships and contact function in a situation where their significance is constituted and confirmed by an outsider’s gaze; the willingness of a viewer—who becomes an audience in such a performance of relations—to acknowledge, analyze and attest the existence of a connection. Contact becomes here a performance and a subject of analysis rather than a mode of being or a goal in itself. Contact understood as a performative act was central in Roquet’s and Kutera’s works that featured camera documentation as a form of mediation that carried the interaction beyond the parties involved. F-Art became a site for negotiation of performative contact as an artistic action as well as artistic praxis.

At F-Art Endre Tót performed a new iteration of his zero-typing action, which he had previously presented in Poland and abroad numerous times since at least 1972.(Detailed analysis of Endre Tót’s practice in the context of the Hungarian socio-political situation as well as his use of humor and the reception of his works is contained in Klara Kemp-Welch, Antipolitics in Central-European Art, (London: I. B. Tauris, 2014), pp. 142–184.) Endre Tót also exhibited previously in Ewa Partum’s Address Gallery in May 1973—following his earlier performance at the Foksal gallery in 1972—where his show was accompanied by the publication of his eponymous work Ten questions, in which all words that could define the content of the questions are replaced by zeros, and the accompanying postcard served also as an invitation to the exhibition. Whereas the invitation featured the English version of the ten questions, larger format prints included a Polish translation of the text, adapting the message to both local and international audiences. Tót’s mail art practice consisted mostly of two continually repeated concepts—typing zeros, and announcements “I am glad if…”(Kemp-Welch, Antipolitics, pp. 142–184.)—which reflected self-censorship and engagement with absence and fragmentary information, as well as the contentment that is derived from an ability to perform even the most mundane activities, or, indeed, to type zeros. Klara Kemp-Welch notes that since 1970 Tót had been concerned with reaching wider audiences abroad and that his “overproduction of incomprehensible messages parodied and performed for a Western audience the dilemma of a Hungarian avant-garde artist seeking to make contact with the outside world.”(Kemp-Welch, Antipolitics, pp. 151–152.) Although Tót managed to reach a number of prominent artists in the West and was one of the few Eastern European mail artists to participate in Jean-Marc Poinsot’s Envois (Mailings) section of the seventh Paris Biennale in 1971, his international travels in the first half of the decade took place in the East. While his self-censorship and irony could have been perceived in the West as curiously “other,” reflecting and reinforcing the Iron Curtain binary, in the other satellite states his self-limiting stance and perverse transparency in its supposed nullity of meaning was welcomed with empathetic understanding of a shared context. Although cultural policies and degrees of permitted artistic freedoms varied between the countries of the Soviet bloc, the comprehension of mechanisms of power and the functioning of the repressive apparatus was shared and—as empirically experienced—rather obvious.

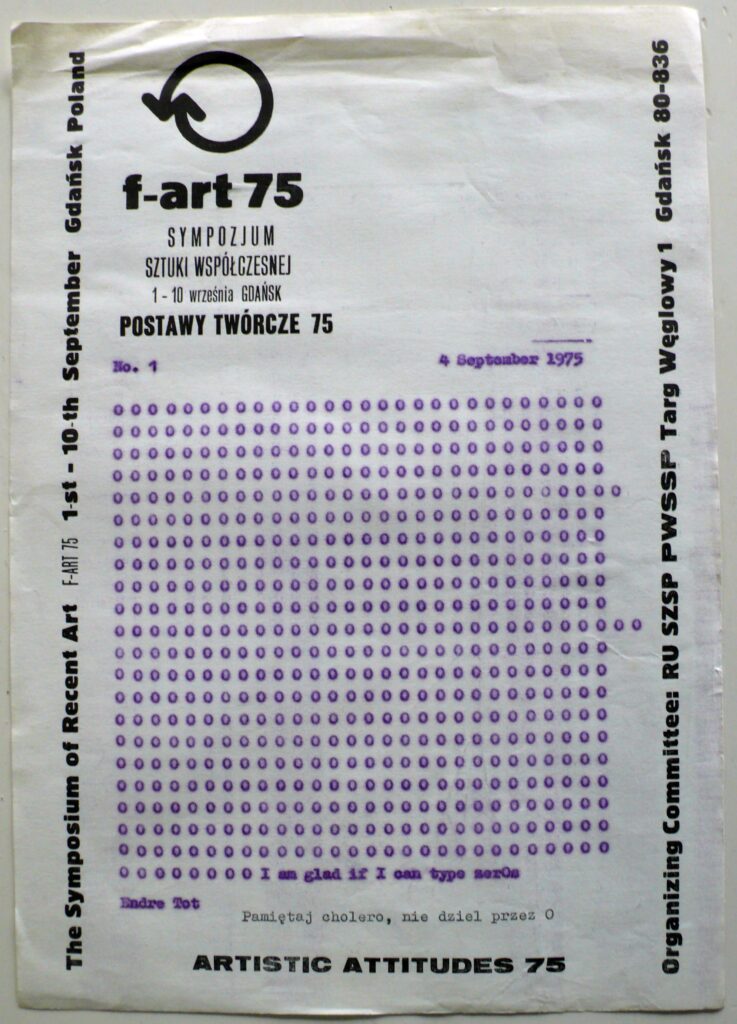

Endre Tót. I’m glad if I can type zeros, 1975. Typescript on paper, 29,7 x 21 cms. Image courtesy of Lomholt Mail Art Archive.

Tót’s action at F-Art, combining performance, mail art activity, and the actual production of the piece, plays with the ambiguous dichotomy of locality and international network that is inherent to the practice. It is safe to assume that his action does not greatly differ from his usual mode of working on his other typewritten zero works. The main difference is the presence of an audience largely consisting of fellow artists watching him type the kind of works they would find in their mailboxes, transforming a secluded activity into a display of a work of ironically glad self-censorship. Questions about the context of creation of a work are reflected in Tót’s use of the F-Art official paper, which included information about the dates, name of the festival, and its organizers, as support for his work. Below Tót’s assertion “I am glad if I can type zeros” there is a sentence in Polish which roughly translates as “remember, you brat, not to divide by zero,” a slightly rude rhyming mnemonic device reminding schoolchildren about this mathematical principle. Added to Tót’s piece, it incorporates a specifically local and playful element that is legible only to those who speak Polish, thus restricting a part of a dialogue to the cultural realm in which it was created. Tót’s work represents a particular conflation of varying modes of being and relating. Personal contacts were linked with distant mail art dialogues, and a potentially unlimited field of mail art was addressed from a very particular local perspective of a situation happening over a very short period.

Croatian conceptual artist—and later filmmaker—Goran Trbuljak reflected on the official, bureaucratic tangent of the F-Art festival, in line with his practice of exposing the ramifications of participation in an institutional system and questioning the role of an artist within it. Trbuljak covered a sealed envelope with official stamps of the union of the Academic Council and Socialist Union of Students that organized the event, highlighting the administrative, state-dependent context of the organization of a counter-culture festival as well as highlighting the context and local specificity informing the work’s presentation. Trbuljak’s other contribution to F-Art festival consisted of twenty-one works from his Galleries series in which a form, including a photograph of a gallery’s façade, stated:

I entered ………. and, not identifying myself (surname, first name, education documentation), asked this question seeking an answer of Yes or No or Maybe: Would you like to exhibit this work in your gallery?

1. Yes.

2. No

3. Maybe

Director of gallery Anonymous Artist(Goran Trbuljak, Artiste Anonyme, 1972–1973. Photograph and ink on paper. Generali Foundation, object number GF0030291.00.0-2005. English translation from French from the Generali Foundation.)

In 1973 Trbuljak changed this tactic of remaining anonymous and continued the project in 1974 identifying himself, and adding his artistic credentials to the form. As the artist had spent two years in Paris before returning to Croatia in 1974, most of the works in the Galleries series were a result of him visiting galleries in Paris and talking to the directors in person. While operating within the logic of the institutional critique they were, crucially, a documentation of specific meetings that reflected the subjective and individual dimension of the art world and the dependence of artists’ careers on singular decisions. Trbuljak’s piece was to a large extent a documentation of rejection and the absence of support.

His presentation at F-Art was accompanied by a letter in a similar format addressed to the festival’s commissioners asking them to put a price on the work. Trbuljak stated their valuation in Paris at 15,000 Francs and suggested the commissioners select one of five price-ranges in Polish Złoty, as such allowing the location of the presentation to determine the work’s potential monetary value and valorization within a specific context. The three organizers responded on the same sheet stating: “we treat this entire piece as a work of art. The idea of the work of art is significant outside the commercial and mercantile system, and this is why we cannot put a price on it.”(Goran Trbuljak, Gdansk Work, 1975. Photo montage black-and-white photograph, typescript text and ink on paper. Generali Foundation, object number GF0030294.05.0-2005.) Trbuljak’s attempt to introduce a mercantile dimension into the event organized by the Socialist Union of Students tackled one of the crucial differences between the Eastern and Western art worlds. Crucially, this work was later mailed—and most likely gifted—to Lomholt, thus exemplifying the amiability and the continuation of contacts following the personal meeting while further mocking the commercialized side of the circulation of art.

The near absence of a private art market in socialist countries, along with drastic discrepancies in exchange rates that made travel to the West very costly, meant that conceptualist dematerialization of the artwork or mail art’s reliance on a form of a gift economy in the East was not primarily construed as rejecting commercialization of the work of art. Trbuljak’s work shown at F-Art was a stark reminder that presence in the West did not guarantee success and perversely highlighted the benefits of artmaking in a situation where art “is significant outside the commercial and mercantile system”, even if it might render it priceless. In comparison to the experiences of artists who, like Tót or Ewa Partum, actively and to some extent successfully sought international contacts, Trbuljak’s stories of rejection complicate a simplistic binary of center and periphery and highlights the significance of individual relations and personal choices as the crucial infrastructures that allow for transregional and international artistic presence. Trbuljak’s joyous yet reticent participation in Anna Kutera’s action at F-Art is one of the traces of how such personal and intimate interactions became the subject and the medium of the neo-avant-garde art that negotiated its international presence and intelligibility with its local relevance.

In 1975 in Poland, mail art constituted an important source of information on international art events and contacts, yet a number of artists sought various opportunities to meet and get to know each other in person. At the same time, as the F-Art festival indicates, the notions of contact and human interaction within the field of art became a crucially important subject explored also outside mail art. This recognition coincides with the apparent change of paradigms in Polish avant-garde art at the time, and 1975 appears to be a moment of re-evaluation of existing approaches and modes of communicating within and outside the networked activities. This transition from dialogue mediated through artworks to personal conversations and projects relying on collaboration at F-Art garnered a multilayered visibility that complicates apparent conventions of East-to-West aspirations. The international symposium became a foundation for projects realized abroad and at home that proposed new models of art and modes of engagement. The presence of experimental international art and visits by foreign artists both from the socialist satellite states and from the West to a large extent resulted from the development of the network both in Poland and in the region, and the particular cultural policies that the artists negotiated and managed to use to their advantage. At the same time, with the change of the mode and intensity of international artistic interactions came different manifestations of contact in art. Several works at F-Art festival reflect an interest in a new aesthetics of contact understood as the mediation of connectedness. This artistic contact not only testifies to an existence or experience of a relation, but also situates it in a specific context incorporating social dynamics, geo-political positioning, and regional specificity.

This article is part of a Special Issue on Regional Resonances. You can read other articles from this Special Issue published on ARTMargins Online below: