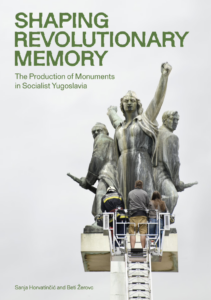

Shaping Revolutionary Memory: The Production of Monuments in Socialist Yugoslavia

Sanja Horvatinčić and Beti Žerovc, eds., Shaping Revolutionary Memory: The Production of Monuments in Socialist Yugoslavia (Berlin: Archive Books, 2023), 424 pp.

Maybe they never really left the public consciousness, but monuments have been at the front of public discussions in the last decade. Despite major world events such as a pandemic and several wars erupting – or possibly precisely because of these major events – there has been significant attention paid to our relationship with public monuments. The so-called “statue wars” in the US and UK of recent years are one example.(Statue wars have been covered in AMO in various articles in recent years.)The fascination with the high modernist monuments on the territories of the Former Yugoslavia is another. Closely related with the fascination with Soviet monuments, the attention to the Yugoslav monuments is slightly more unique, possibly because of their distinctive aesthetic, and possibly because of their complex and unresolved historical legacy.

Another reason for the uniqueness of Yugolsav monuments is the amount of attention paid to them in publications. Monuments to World War II from Former Yugoslavia have enjoyed considerable attention in the literature, and some of the key authors of such publications are included in this book. In different ways over the last 15 years, these authors have engaged with the history, legacy and afterlife of these monuments. As such, this book makes an excellent starting point for anyone interested in getting into the topic in more detail. Billed as an expansion of the course reading material for a postgraduate course at the University of Ljubljana, the anthology does have the feel of a course book. It is clearly structured, it has well-defined aims and it is pitched to a specific demographic. The individual chapters are for the most part strongly argued and engaging, which is unsurprising given that the authors are mostly well-known names in this area. Even though much of this material is available elsewhere it is good to see it all collected into a single volume.

Following a short introduction by the editors Sanja Horvatinčić and Beti Žerovc, the book starts with a chapter by Žerovc exploring the cultural and political landscape of Yugoslavia from the late 19th century to the end of the First World War. The chapter establishes the way in which a diverse cultural space with very different memories regarding certain historical events were tentatively unified through monuments. The chapters by Haike Karge and Horvatinčić examine the memory canon and strategies of production in monument production, highlighting the conceptual, artistic and political challenges faced in the year during and after the construction of a monument. Sabina Tanović examines the same material from an architectural perspective, placing monuments in the context of broader professional architectural trends in Yugoslavia 1960-1980. These chapters provide a solid historical overview of monument production and identify some of the key underlying issues around monuments that only became more pronounced in the later years.

Following a short introduction by the editors Sanja Horvatinčić and Beti Žerovc, the book starts with a chapter by Žerovc exploring the cultural and political landscape of Yugoslavia from the late 19th century to the end of the First World War. The chapter establishes the way in which a diverse cultural space with very different memories regarding certain historical events were tentatively unified through monuments. The chapters by Haike Karge and Horvatinčić examine the memory canon and strategies of production in monument production, highlighting the conceptual, artistic and political challenges faced in the year during and after the construction of a monument. Sabina Tanović examines the same material from an architectural perspective, placing monuments in the context of broader professional architectural trends in Yugoslavia 1960-1980. These chapters provide a solid historical overview of monument production and identify some of the key underlying issues around monuments that only became more pronounced in the later years.

The inclusion of an interview with art historian Bojana Pejić as a chapter is somewhat puzzling, given that it is based on her doctoral dissertation. While Pejić is undoubtedly a key voice in this area and offers significant insights that contribute to the conversation, the interview’s approach of looking at the broader visual culture of Yugoslavia feels more lightweight compared to the other chapters. It reads like series of broad reflections on the changes to the visual culture and ideology of Yugoslavia and its dissolution. Perhaps an inclusion of a chapter from Pejić’s unpublished thesis would have been a better choice.

Marija Djordjević’s chapter examines community events and public performances connected to the Yugoslav monuments, providing an important counterpoint of perspective ‘from below’. Vladimir Kulić discusses the fetishization of Yugoslav monuments in the last two decades, providing a broader perspective on how Yugoslavia’s cultural and revolutionary heritage is taken up, repurposed and recycled in contemporary media. Kulić also reflects on the use of monuments as memes, advertising material and backdrops for influencer social media posts: a timely discussion of the intersection of remnants of 20th century high modernism and 21st century hyper-production of images.

Horvatinčić and Žerovc each have a second chapter included in the book that take the approach of historical evaluation. Horvatinčić critically examines ideas around authorship and problematic gender politics around the monuments, while Žerovc examines the unresolved legacy of the Yugoslav monuments somewhere between works of architecture/sculpture and failed social projects. These two chapters seem the most unfinished and read more like the start of future projects than as their written realization. While these chapters hint at an interesting future direction of the historical examination of monuments, I wonder if the space they occupy in the book would have been better offered to other voices from the region that fall outside of the standard cultural axis of Ljubljana-Belgrade-Zagreb, which is sadly reinforced in this publication.(This may sound like a local gripe, but for a book dealing with collectivism and collective identity in the territories of Former Yugoslavia, I believe it is significant. It has now become almost customary to overlook voices from Bosnia and Herzegovina, North Macedonia, Kosovo, and Montenegro.)

The key strengths of this book are the clarity and strength of the material it contains. Its chronological approach is tried and tested, and it works here as well. We start with the historical precedents for the monuments, the first iterations of the idea for them, and we then shift through their history during WWII and immediately after WWII. We then examine the way in which the discourses surrounding the monuments developed in the later years of Yugoslavia’s existence, and the way in which their eventual construction coincided with significant political events that led to the dissolution of the country. The final section of the book looks at the position of the monuments during and after the Yugoslav wars: the destruction, the appropriation, the neglect.

The publication is richly illustrated, including photographs of many monuments that have been destroyed, such as the Monument to the Battle for the Wounded at Makljen that was devastated in 2000. The book also includes illustrations in individual chapters, as well as a special 50-page chapter dedicated solely to visual material. The authors and editors made full use of the access to archives in Croatia and Slovenia they were granted. I was very excited to see some of these photographs, and the personal touch (many are from private collections) made them particularly engaging. Notable images include families on picnics and high school children on organized visits to some of these monuments, illustrating the nexus of state ideology reinforced through staged pedagogical rituals with childhood memories. It strikingly demonstrates the ways in which the state ideology of socialism entered the private sphere. The backdrop of monuments that have since been destroyed gives the pictures a mournful note.

There are two main problems with the publication, and they both revolve around the most common objection to collected anthologies: what is included and not included. Regarding what is included, a good portion of the material here is recycled from the participating authors’ previous work. For example, Karge, Horvatinčić and Kulić all provide a slightly edited version of already published research.(Horvatinčić and Kulić were both involved in the exhibition Toward a Concrete Utopia: Architecture in Yugoslavia 1948-1980 held at MoMA 2018-2019, which included a publication of material in an exhibition catalogue and online. See https://www.moma.org/calendar/exhibitions/3931 accessed 28 March 2024. Heike Karge’s PhD on Yugoslav monuments was published in German, translated and published as articles in English and published in Serbian 2014 as Sećanje U Kamenu: Okamenjeno Sećanje, XX Vek, Belgrade.) This is not a problem per se, and it often happens in edited collections, but it does raise the question regarding what is the new contribution to knowledge here? Or, was the point to provide a comprehensive overview of the existing literature on the topic?

Regarding what is not included, in addition to the omission of voices outside of the cultural axis of Ljubljana-Zagreb-Belgrade, the publication contains a significant conceptual oversight. Shaping Revolutionary Memory is based on three key claims: to provide a comprehensive overview of memorial production and practices around monuments; to take a chronological approach, tracing the monuments from the origin of the idea to the present; and to pay close attention to the relation of the monuments to the different ‘post-separation, post-socialist’ realities of the Yugoslav successor states. While the book does deal with contemporary visual culture and the mass appropriation and circulation of images of monuments online (as in the chapter by Kulić), it completely ignores the rich and substantial body of artistic practices that have engaged with the legacy and continued relevance of the monuments. This body of work, however, is significant in that it not only stands apart from the broader visual culture but in that it is often articulated as a critique of it. Adela Jusić, Jasmina Cibic, David Maljković, Aleskandra Domanović, Igor Bošnjak, Mladen Miljanović, Siniša Labrović are some of the artists whose work has engaged with the reception, legacy and afterlives of these monuments.(There are numerous other artists, designers and architects from the region I did not mention. For an illustrative example of this body of work, see the discussion of Miljanović’s work in ARTMargins Online: https://artmargins.com/realtime-monument-interview-with-mladen-miljanovic/.)

In one sense, this criticism can be chalked up as the version of the familiar trope “the book I would have liked to see rather than the one that I was asked to review.” But in fact, the omission is more than just a gripe from an informed art theorist for the omission of this artistic body of work ignores the crucial way in which monuments not only continue to live in the public sphere, but may, beyond that, also mobilize the past as an expression of what Igor Štiks describes as the ‘new left’ in post-Yugoslav spaces: a critique of the neoliberal capitalist transformation of the post-Yugoslav societies; of the conservative, religious, patriarchal and nationalist hegemony that has accompanied that transformation; and of an anti-nationalist approach to the region.(Igor Štiks, ‘“New Left” in the Post-Yugoslav Space: Issues, Sites, and Forms’, Socialism and Democracy 29, no. 3 (2015): 135–46, 137.)

The ways in which the aforementioned artists use the images of monuments mobilize the emancipatory social, political and class structure of Yugoslavia: the notion of ‘social property’ and of worker self-management; the conception of a moderate socialist welfare state; and of Non-Aligned international politics. This is not just a case of art ‘about’ monuments, but of art that captures erased histories of emancipation through its engagement with monuments. Art that captures abandoned pasts and fictionalized futures.(Another notable omission in the book – which is less problematic than the missing artistic practices, but curious nevertheless – is no discussion of the hyper-production of monuments after the nineties. This is a phenomenon that mirrors the production of s in significant ways and the discussion would potentially be very productive for providing a more complete contemporary context.)

As it stands, Shaping Revolutionary Memory treats the Yugoslav monuments as a completed body of work. It does this because it fails to acknowledge one of the main ways in which monuments continue to be engaged. The reality is, however, that these monuments continue to resonate in the region, often in problematic ways, but nevertheless in ways that are important to note. Despite these strictures, the collection is to be commended for its meticulous approach, quality image reproductions, and high standard of book design. It will make a great starting point for any student of Yugoslav monuments.