Axis Mundo: Queer Networks in Chicano L.A.

Hunter College Art Galleries, June 21–August 19, 2018

In 1970, the influential Chicano artist Carlos Almaraz created a series of minimalist collages. Superimposing select magazine cutouts—including pornographic images of women, male physique models, and animals—over a piece of grid paper, Almaraz disrupted the structure of the ordered field while using the grid to visually connect disparate images across the picture plane. Exhibited as part of Axis Mundo: Queer Networks in Chicano L.A. at the Hunter College Art Galleries in New York, Almaraz’s gridded collages convey some of the show’s most vital concepts: they defy a narrative centered on a singular subject, instead focusing on interconnections that imagine creative modes of living.

Installation view of Axis Mundo: Queer Networks in Chicano L.A. at 205 Hudson Gallery and the Bertha and Karl Leubsdrof Gallery. Photo by Stan Narten. Courtesy of Hunter College Art Galleries.

Axis Mundo was organized by ONE National Gay & Lesbian Archives at the USC Libraries with The Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles as part of the Getty initiative Pacific Standard Time: LA/LA, and traveled to the Hunter College Art Galleries this past summer. With over fifty artists presented between two of Hunter’s exhibition spaces, Axis Mundo, as posited by curators C. Ondine Chavoya and David Evans Frantz in the exhibition’s opening statement, confronts the “direct and indirect connections [that] led to shared content and affiliated aesthetic strategies” throughout Los Angeles and beyond, which “constituted a form of queer worldmaking” from the late 1960s to early 1990s. The period under consideration witnessed the rapidly growing fight for civil rights through the Chicano Movement and gay and women’s rights activism, as well as the struggle by AIDS activists to receive recognition and support from U.S. politicians and institutions. One of the strongest aspects of this intelligent exhibition is that the various works all communicate the urgency of such issues, but through examples that are both explicit and subtle. The queer Chicana/o artists and their collaborators who are the subjects of this exhibition cannot be encapsulated by any one definition of sexuality, gender, or race.(Although the more recently established gender-neutral term Chicanx is productive, I use the form Chicana/o in this review to maintain the form used by Chavoya and Frantz in their catalogue texts.) As such, Axis Mundo is committed to exploring queer directionalities, meaning the paths and courses of action that artists took to establish the “physical and conceptual spaces where these identities flourished and intersected.”(David Evans Frantz, “Chicano Chic: Fashion/Costume/Play,” in Axis Mundo: Queer Networks in Chicano L.A. (Los Angeles, CA: ONE National Gay & Lesbian Archives at the USC Libraries), p. 68.)

Installation view of Axis Mundo: Queer Networks in Chicano L.A. at 205 Hudson Gallery and the Bertha and Karl Leubsdrof Gallery. Photo by Stan Narten. Courtesy of Hunter College Art Galleries.

The exhibition developed out of meticulous research into the life and work of artist Edmundo “Mundo” Meza (1955–85). Born in Tijuana and raised in East Los Angeles, Meza forms the core of the exhibition’s proposed network. Despite his short life, Meza produced numerous daring and multidisciplinary collaborations with artists such as Gronk and Robert Legorreta (also known by his performance persona, Cyclona). Beyond highlighting Meza, the title Axis Mundo indicates that directionality and orientation are central to the exhibition’s thesis. This orientation can be openly interpreted, whether in terms of sexual or physical orientation, among many other definitions. The exhibition astutely proposes an interpretation of how a network centered on queer Chicana/o artists charted its way through, across, and beyond Los Angeles amidst institutional oppression, the wave of civil rights movements, and the AIDS crisis. The spaces that these creators inhabited, and the way they oriented themselves in such spaces, are clarified through Axis Mundo’s wide array of works. In Queer Phenomenology: Orientations, Objects, Others, cultural studies scholar Sara Ahmed offers a point of entry into the significance of space and time in relation to queer directionality. Arguing for a queer phenomenology, Ahmed proposes a “model of how bodies become oriented by how they take up time and space.”(Sara Ahmed, Queer Phenomenology: Orientations, Objects, Others (Durham; London: Duke University Press, 2006), p. 5.) Disrupting straight paths—defined as predetermined, whether heterosexually constructed or otherwise—the artists in Axis Mundo oriented and disoriented space with the queer body.

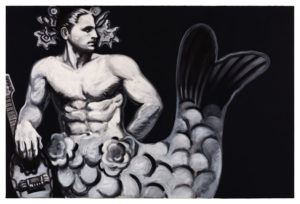

Mundo Meza, “Merman with Mandolin, “1984. Acrylic on canvas, 72 x 111 in. Collection of Jef Huereque. Photo by Fredrik Nilsen

Familial relationships were crucial to many of the artists in Axis Mundo. Diverging from patriarchal order, these families did not impose strictly defined domestic roles, and several works demonstrate how the queer family became a refuge in which to establish oneself. Ricardo Valverde’s video Mujeres (c. 1974) captures a dialogue between him and his sister Maya on her thirtieth birthday not long after she came out as a lesbian. In the video, Maya discusses how she lives in a collective with her children and other women. It is displayed next to the flyer announcement for Valverde’s 1976 MFA thesis show titled Cambios en la familia (Changes in the Family), which examined the realignment of familial dynamics towards broader social structures. Returning to Ahmed, she argues that occupying space involves “a dynamic negotiation between what is familiar and what is unfamiliar.”(Ibid., p. 7.) In other words, the familiar is formed by unprecedented movements towards objects that are already in reach. For Valverde, his subjects, and others, the nuclear family was a recognizable structure ready to be dismantled and reoriented.

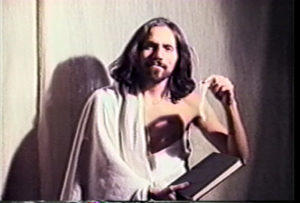

DIVA TV, Still featuring Ray Navarro from “Like a Prayer,” 1990. Digitized VHS video, 28 min. Ray Navarro Papers and Videos. ONE National Gay & Lesbian Archives at the USC Libraries.

The reorientation of traditional spaces was a tactic that artists often used to penetrate the domains that had rejected them. While this approach was implemented to reconfigure the patriarchal family, it was also employed to infiltrate highly visible public space such as the Catholic Church. Of the many compelling videos on view, the most captivating are the excerpts featuring Ray Navarro from Like a Prayer (1990). A founding member of DIVA TV (Damned Interfering Video Activist Television)—the video affinity group of ACT UP/New York—Navarro worked to educate AIDS activists outside of the mainstream television networks which, as the video shows, refused to acknowledge the urgency of the AIDS crisis. The video includes excerpts from Stop the Church, a protest staged at St. Patrick’s Cathedral in New York City against the Catholic Church coinciding with the Archbishop’s visit in 1989. The protest focused on the Church’s destructive views on AIDS education, gay civil rights, and women’s reproductive rights. Infiltrating the Church and major news channels, these activists oriented themselves within the very spaces from which they had been excluded.

Mundo Meza, Documentation of a window display at Maxfield Bleu, West Hollywood, c. early 1980s. Photo by Mundo Meza. Courtesy of Pat Meza.

The department store window display, a different space but no less sacred for some, was another arena to be subverted. Mundo Meza is extensively represented by his imposing yet introspective paintings, however, photographic documentation of his early 1980s window displays for the West Hollywood department store Maxfield Bleu emphasize his rebellious nature. Working with Simon Doonan, a British designer who would go on to become a major figure in the fashion world, the pair used dark humor and provocation to usurp the highly visible site. Photographs of the duo’s most scandalous yet famous project show a window parodying the recent abduction of a young child by a coyote. Complementing high fashion with campy props and inflammatory scenarios, Meza and Doonan shrewdly concretized their own place within the fashion sphere while bewildering and offending Los Angeles’ elite.

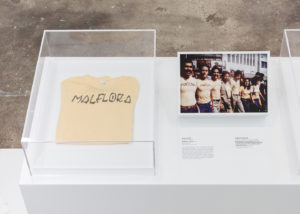

Beyond the spatial opportunities afforded by the department store window, clothing became a means to circulate and establish queerness in public. In 1976, Joey Terrill, a recurring figure throughout Axis Mundo, began producing yellow T-shirts with either the word maricón or malflora emblazoned on the front. Terrill’s use of such words—Spanish slang for faggot or lesbian—reclaimed the pejorative terms and injected them into the space that the wearers entered. Created to be worn in resistance to the lack of Latina/o representation in the Gay Rights Movement, as well as in the face of the homophobia in Chicano culture, the shirts not only circulated but also created space within an antagonistic context.(Leticia Alvarado, “Malflora Aberrant Feminities,” in Axis Mundo: Queer Networks in Chicano L.A. (Los Angeles, CA: ONE National Gay & Lesbian Archives at the USC Libraries), p. 95.) For his analysis of Terrill’s T-shirts, David Evans Frantz logically turns to José Esteban Muñoz’s idea of disidentification, which, as Frantz describes, “conceives of how minority subjects negotiated and created space within an often hostile culture—from the larger progressive groups in which they sought to intervene, reclaiming the insult as a politically mobilizing group identity.”(Frantz, 68; see also José Esteban Muñoz, Disidentifications: Queers of Color and the Performance of Politics (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1999).) Terrill’s project clearly had an impact. Two decades later, with the AIDS epidemic posing a new challenge to queer communities, Argentine artist Roberto Jacoby would implement a similar strategy by creating a T-shirt with the statement “Yo tengo SIDA” (I have AIDS) to contest the prejudice around the devastating disease.

Installation view of Axis Mundo: Queer Networks in Chicano L.A. at 205 Hudson Gallery and the Bertha and Karl Leubsdrof Gallery. Photo by Stan Narten. Courtesy of Hunter College Art Galleries.

Muñoz’s theories are also productive for questioning how these artists sought alternative spaces to cultivate and exhibit their own work. ASCO, a group composed of Harry Gamboa Jr., Gronk, Willie Herrón III, and Patssi Valdez that formed in 1972 following the Chicano Moratorium, explored diverse artistic forms that included performance and ephemeral practices. Commenting on the lack of Chicana/o representation in movies, ASCO created the No Movie: faux film stills featuring dramatically stylized characters in elaborate yet familiar cinematic scenes. These images were distributed on postcards and dispersed through the mail to local and international media outlets. Re-envisioning the role of the Chicana/o in film, the No Movie imagined the possibility of Chicana/os as movie stars while concurrently stressing their underrepresentation. By circulating these postcards to larger institutions, the works functioned as a form of infiltration and a means to establish space within a context that normally relegated Chicana/os to the margins.

Installation view of Axis Mundo: Queer Networks in Chicano L.A. at 205 Hudson Gallery and the Bertha and Karl Leubsdrof Gallery. Photo by Stan Narten. Courtesy of Hunter College Art Galleries.

In fact, several of the figures represented in Axis Mundo implemented circulatory artistic practices as processes of disidentification and self-orientation. Publications such as Homeboy Beautiful (edited by Terrill), Egozine, Jockstrap, and Cabaret Voltaire operated as alternative exhibition spaces. As inexpensive and readily accessible formats, magazines and postcards decentralized artistic space while also extending outwards to new audiences.(C. Ondine Chavoya, “Exchange Desired: Correspondence into Action,” in Axis Mundo: Queer Networks in Chicano L.A. (Los Angeles, CA: ONE National Gay & Lesbian Archives at the USC Libraries), p. 219.) As such, Axis Mundo points to how these queer networks sought to establish their own domains, but also reach towards uncharted territory through innovative distribution circuits.

Installation view of Axis Mundo: Queer Networks in Chicano L.A. at 205 Hudson Gallery and the Bertha and Karl Leubsdrof Gallery. Photo by Stan Narten. Courtesy of Hunter College Art Galleries.

Both Ahmed and Muñoz argue for the importance of the unknown in queer ideologies. For Ahmed, the politics of disorientation puts new possibilities within reach, and for Muñoz, “the future is queerness’ domain.”(José Esteban Muñoz, Cruising Utopia: The Then and There of Queer Futurity (New York: New York University Press, 2009), p. 1; Ahmed, pp. 9–10.) Therefore, the question becomes how a historically-grounded exhibition can work to orient objects for future viewers while also continuing to embody these objects’ original, disorienting nature? While the answer is not quite clear, an anecdote from Axis Mundo’s New York opening sheds light on the complexities that shows of this nature face. That evening, a scholar of Latin American art circulated through the gallery wearing one of Terrill’s maricón T-shirts. The shirt fit right in, which on the one hand suggested that it had already become historically oriented. On the other hand, the renewed circulation of the shirt proposed the disorienting question of its own place within future artistic spheres. Perhaps the answer to such a conundrum will only be revealed in the future.