Central and Eastern European Art: 30 Years After the Fall

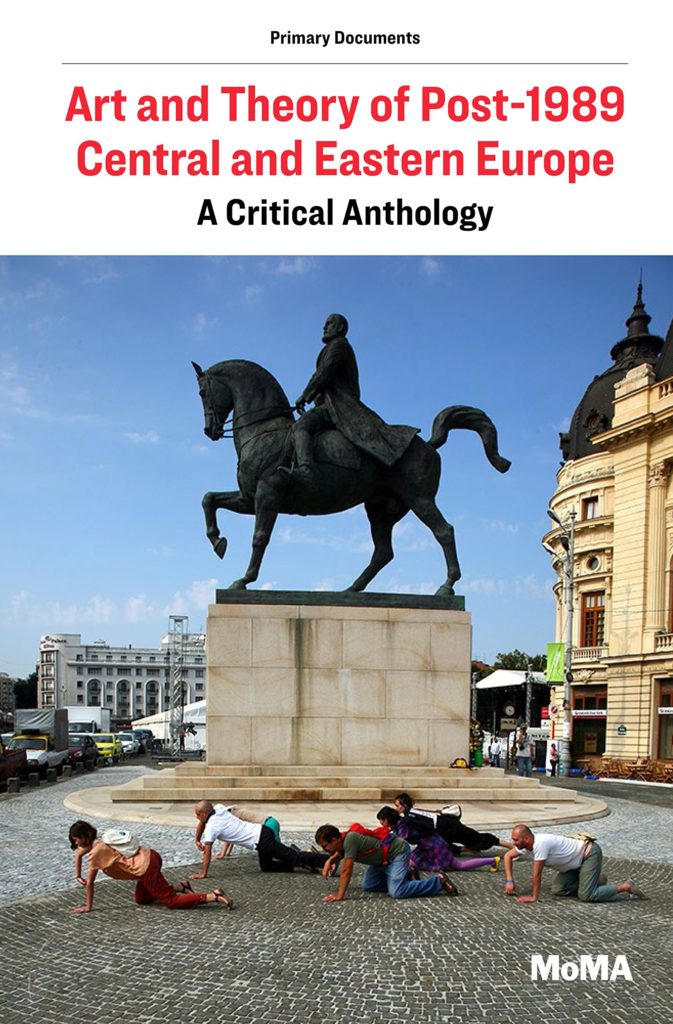

Ana Janevski and Roxana Marcoci with Ksenia Nouril (eds.), Art and Theory of Post-1989 Central and Eastern Europe: A Critical Anthology (New York: The Museum of Modern Art, 2018), 408 pp.

“To give a definition of Eastern Europe is a difficult or almost impossible task” (p. 279). This observation, offered by artist Sanja Iveković in an interview featured within Art and Theory of Post-1989 Central and Eastern Europe, neatly captures the challenge that the volume sets for itself. Elsewhere within this new addition to the Museum of Modern Art’s series of critical anthologies, curator Raluca Voinea evokes the difficulties encountered by Western visitors in describing the Balkans at the beginning of the 20th century, having found the region’s geography simply too complicated, its ethnography too confused, its history too intricate, and its politics too inexplicable (p. 106). It is telling that—more than a century later—these perceptions endure, and are often easily extended to the entire eastern half of the European continent. Indeed, well into the 21st century some Western European officials still find themselves unable to distinguish their Slovenia from their Slovakia, and hold only the vaguest of notions as to the line of demarcation that was the Iron Curtain. In this context, the team at MoMA takes on the ambitious task of (re)positioning this contentious region in light of the tremendous political and creative transformations that have occurred since the fall of communism.

Bringing together a sizable international team of artists, curators, editors, translators, and researchers, Art and Theory of Post-1989 Central and Eastern Europe is a product of MoMA’s Contemporary and Modern Art Perspectives (C-MAP) research program, which examines art histories beyond the North American and Western European canon. The anthology, edited by Ana Janevski and Roxana Marcoci with Ksenia Nouril, presents an extension of the work that informed the inaugural collection in this series, Primary Documents: A Sourcebook for Eastern and Central European Art since the 1950s—a 2002 publication that brought together primary sources pertaining to artistic production from this region during the second half of the 20th century, with an introduction penned by conceptual artist and noted non-conformist Ilya Kabakov. With the new volume, the editors extend their focus to the post-socialist era, presenting seventy-five primary and secondary sources that reveal “the massive changes and ripple effects that the dismantling of socialist regimes across Central and Eastern Europe had on artistic practices and critical theory of the last thirty years” (p. 12). Structured around seven thematic chapters, the collection assembles a vast range of materials originally written in over a dozen languages, including excerpts from academic studies, exhibition catalogues, art journals, collections of artists’ writings, as well as critical texts and interviews commissioned specifically for the volume. This kaleidoscopic approach effectively captures the complexity of artistic engagement with phenomena explored throughout individual chapters—from historical legacies to future alternatives—and the wealth of creative strategies that emerged in the process.

Bringing together a sizable international team of artists, curators, editors, translators, and researchers, Art and Theory of Post-1989 Central and Eastern Europe is a product of MoMA’s Contemporary and Modern Art Perspectives (C-MAP) research program, which examines art histories beyond the North American and Western European canon. The anthology, edited by Ana Janevski and Roxana Marcoci with Ksenia Nouril, presents an extension of the work that informed the inaugural collection in this series, Primary Documents: A Sourcebook for Eastern and Central European Art since the 1950s—a 2002 publication that brought together primary sources pertaining to artistic production from this region during the second half of the 20th century, with an introduction penned by conceptual artist and noted non-conformist Ilya Kabakov. With the new volume, the editors extend their focus to the post-socialist era, presenting seventy-five primary and secondary sources that reveal “the massive changes and ripple effects that the dismantling of socialist regimes across Central and Eastern Europe had on artistic practices and critical theory of the last thirty years” (p. 12). Structured around seven thematic chapters, the collection assembles a vast range of materials originally written in over a dozen languages, including excerpts from academic studies, exhibition catalogues, art journals, collections of artists’ writings, as well as critical texts and interviews commissioned specifically for the volume. This kaleidoscopic approach effectively captures the complexity of artistic engagement with phenomena explored throughout individual chapters—from historical legacies to future alternatives—and the wealth of creative strategies that emerged in the process.

The volume opens by examining the ways in which artists, curators, and historians who lived through socialism and witnessed its collapse engage with this history in their works. A conversation with Hungarian artists Katalin Ladik and Tamás St.Auby sets the scene: born and raised in Yugoslavia, Ladik recounts some of the significant artistic freedoms she enjoyed as a poet, actor, and performance artist during socialism. This description contrasts sharply with St.Auby’s memories of socialist Hungary, where his artistic experiments—grounded in Fluxus practices including happenings, action-poems, and mail art—led to official persecution and exile. The breakdown of socialism sees a complete reversal of roles, with Ladik now forced into exile by oppressive nationalist regimes in Yugoslav successor states, and St.Auby returning to Hungary where many former dissident artists had become part of the art establishment, and fashionable subjects for doctoral theses. While Ladik continues to draw inspiration for her work from “late, multicultural Yugoslavia” (p. 25), St.Auby has worked extensively on digitizing artworks from the socialist era that had been banned at the time of their production, noting that these past struggles might sadly still be relevant today.

Subsequent contributions further explore the notion of Eastern Europe as a battleground for cultural influence between Cold War superpowers; different ways in which Eastern European artists employed modernist, avant-gardist, and neo-avant-gardist practices to advance or subvert the interests of political elites; the role of dissident groups in dismantling socialist regimes; and the efforts of artists to communicate across the East-West divide. What is clear is that the ideological tensions that underpinned and energized artistic production under socialism have lost none of their provocative edge. In an interview included in the volume, artist David Maljković provides telling insight into how the Yugoslav brand of socialist modernism—which combined a predilection for abstraction with an emphasis on monumentality—has today become a target of nationalist governments. Across the countries of the former Yugoslavia, efforts to establish new national ideologies have been underpinned by systematic erasure of any notion of cultural continuity with the former state—along with the principles of internationalism, emancipatory politics, and supra-national identity that had been so powerfully captured by generations of Yugoslav artists.

The ensuing second chapter is dedicated to Eastern European exhibition history since 1989. Bringing together materials written between the mid-2000s and 2014, this section focuses primarily on large-scale survey shows held in North America and Western Europe, and traces the dominant curatorial trends in exhibiting Eastern European artistic production over the past thirty years. An introductory essay by art historian Claire Bishop describes the craze for the art from the ‘former East’ immediately following the raising of the Iron Curtain as something of a “curatorial safari,” with Western curators “hunting for discoveries in the newly open territory” and bringing these artworks back as trophies (p. 67). After 2000, the curatorial approach would shift to exhibiting art from “Central and Eastern Europe,” with particular attention being paid to the Balkans—a region that, in the wake of the Yugoslav wars, would once again emerge as an ideal backdrop for projecting orientalist fantasies. The concept of exhibiting the ‘post-Soviet’ space, and in particular Russia and Central Asia, would develop in parallel with a curatorial construction of the so-called ‘New Europe,’ with numerous shows foregrounding Europe as a united construct following the absorption of the Eastern bloc into the European Union. The texts assembled in this section provide both a valuable historical survey and an insight into the tense process of renegotiating familiar categories of East and West, center and periphery, Europe and the Other. While the focus in this section is primarily on international exhibitions, selected material here also reveals the emergence of self-historicizing processes—research and curatorial projects launched by smaller galleries and independent entities in the region seeking to articulate Eastern European art histories in their own voice.

This account provides a good segue into a chapter dedicated to archives—a concept that has and continues to play a major role in Eastern European creative practices as a method of preserving, subverting, and resisting. In offering his reading of Ilya Kabakov’s installation Sixteen Ropes (1984) as a form of archive, art historian Sven Spieker reminds us that “stringing up” or suspending objects in a line is the most ancient method of filing, with ‘string’ (fil in French) the origin of English term to file (p. 149). A series of texts in this section expand on the concept of (self-)filing as a strategy for recuperating the history of artistic practices “that were neither supported or documented by official art bureaucracies” (p. 135). Here, as curator Zdenka Badovinac notes, artists become their own art historians and archivists—a strategy that was just as important for preserving progressive artistic practices under socialist regimes as it is today under increasingly conservative governments. A piece by critic and curator Tomáš Pospiszyl engages with the question of state surveillance under communism and the artistic subversion of this practice, exemplified in Jiří Kovanda’s Prague performances of the mid-1970s. When photographed by his collaborators, Kovanda’s seemingly innocuous public activities—walking down the street, brushing up against other pedestrians—would suddenly become records of his (artistic) existence. Kovanda’s statement that these projects were apolitical in nature presents a challenge for viewers, who rightly doubt the political neutrality of these acts of mimicry. This examination of the phenomenon of surveillance seamlessly expands into the contemporary context, saturated as it is by consumer culture and its insatiable appetite for our personal data.

Importantly, a piece on artist Lia Perjovschi and the shift in her practice from body art to the creation of a corpus of research materials pertaining to international art frames a set of texts that foreground the archive as a site of resistance. The act of collecting, studying, and sharing of sources on contemporary art in Perjovschi’s practice takes on the shape of a ‘living archive’—an organic assemblage of alternative bodies of knowledge that challenge official narratives, and help us to imagine alternatives. The concept of a living archive, and the intersection between performance and archival theory intimated here is unfortunately not further explored, despite the emergence of an important trend that has seen contemporary artists use their own bodies as sites of memory, as literal living archives, exemplified in the works of, for example, performance artists Tanja Ostojić or Petr Pavlenskii. Yet the artistic archive as a repository of alternative knowledge (and thus a platform for reimagining a different, better future) does reverberate across the volume. Indeed, this concept is beautifully captured in an interview with filmmaker and artist Hito Steyerl, who suggests that perhaps the most important thing art can do today is to “look, listen, and interpret with precision, imagine without compromise or fear” (p. 346).

Arguably the two most absorbing sections within this anthology are the central pair of chapters that examine how artistic practice and critical theory engage with two major themes: the crisis of democracy, and the potential for collective action. In each chapter, a series of intriguing texts not only reveal the “post-communist condition” in its full complexity, but also trace how “post-socialist” became a global condition. Cultural critic Boris Buden opens with a piece that recounts how democracy “turned stale” in the eyes of Eastern Europeans. The explanation is as confronting as it is simple: following the end of communism, Eastern Europe saw the introduction of Western (rather than ideal) democracy, which arrived with all its internal contradictions, a legacy of colonialism and inequity, and was accompanied by the most predatory form of capitalism. Disenchantment was immediate; the impact long-lasting.

Spanning the period between 2001 and 2012, contributions in this section reveal the effect that the transition from socialist to free market systems had on civil society more broadly and art specifically in Central and Eastern Europe, as the state withered away to make space for economic rationalism. In a stand-out piece, sociologist Ratko Močnik asks whether the East’s past will become the West’s future, as the state of crisis—once applied exclusively to the East—is now the West’s reality. Elsewhere, this levelling facilitated the introduction of the term “former West”—a counterpart to the label “former East” used to denote the fact that the West no longer serves as a reference point for emancipatory ideals. In response, the ensuing chapter asks whether art can save us from the current state of perpetual crisis. Here emphasis is placed on the shift towards collective practices in Eastern European art as a reaction against the politics of individualism and isolationism, as well as the state’s withdrawal from fields of life that were previously, as historian Ilya Budraitskis explains, “part of its organic sphere of responsibility” (p. 243). In this way, art becomes a method for articulating new forms of solidarity and reconstituting a sense of community. Importantly, these texts collectively reveal the emergence of new “post-socialism” within this practice, which emphasizes an organic link (rather than a break) with socialist experience, a vantage point from which to imagine new forms of transnational solidarity, public good, and emancipatory politics.

Discussions of gender discourse and the position of Eastern European art within the contemporary global context form the final portion of Art and Theory of Post-1989 Central and Eastern Europe. The selected texts on gender present an exceptional effort to map the complex relationship between socialism and gender, as well as the trajectories of exchange between Western and socialist feminist circles. The legacies of the revolutionary approach to gender—where the common fight for a communist future took precedence over anything else —would reverberate in the post-socialist era, where efforts to surpass the chaos of 1990s were again framed as a “genderless struggle” (p. 288), notwithstanding the fact that women, as in any crisis, were disproportionally affected. This point is made powerfully through the inclusion of Ostojić’s web project Looking for a Husband with EU Passport (2000–05), in which the artist is photographed completely naked and depilated, appearing more like a specter than a bride, with text below inviting suitors with a European Union passport to get in touch. The trauma of transition had specific and profound effects on women, and scholars of Eastern European art will find this chapter particularly valuable as an exploration of the history of gender discourse in art—a field that remains in great need of further research.

The closing chapter, which is dedicated to the position of Eastern European art within the contemporary global context, exemplifies the editors’ kaleidoscopic approach to their material. Here a discussion of the Non-Aligned Movement—established in 1961 in Belgrade as an alliance of states seeking to transcend the bi-polar Cold War world—extends into texts that provide critical readings of the socialist principle of internationalism as the polar opposite to the notion of globalization, which is grounded in competition, individualism, and highly compatible with extreme conservativism. While these texts go to great lengths to place Eastern Europe in the world both during and after socialism, a text by art group Slavs and Tatars powerfully captures the Eastern European perennial experience of displacement—a sense of never quite being at home (whether at home or not), which has remained constant throughout 20th and 21st centuries, irrespective of ruling regime:

The country we call home, the country we used to call home, and the country we dream to call home are all very distinct and disparate places. It is the result of a productive schizophrenia: we are in all of them at once, a ravishing sensation but one tempered by the slow, sobering devastation of never being in any one entirely (p. 365).

Expansive and enthralling, Art and Theory of Post-1989 Central and Eastern Europe stands out for both its intellectual rigor and its commitment to tackling complexity. It is also energizing in its insistence that art can and must change the world. Indeed, the volume unapologetically casts the artist as a political actor, with philosopher Boris Groys emphasizing that true contemporary art is “much more open and inclusive than the national societies” because it provides a “territory that accepts everybody and everything” in a world that is “becoming increasingly conservative and restrictive” (p. 341). Equally, however, it appears difficult for MoMA to resist its reputation as an institution that defines the canon, and this leaves the volume with some blind spots. First, the anthology materials are characterized, without critical reflection, as ‘primary documents,’ despite the fact that a significant portion of the volume in fact comprises secondary sources. Compounding this issue, while the volume captures the voices of a well-established cohort of artists and curators, it does so almost exclusively.

The inclusion of a wider range of artists, curators, art historians, and theorists might have lent greater nuance to certain sections, and indeed to the anthology as a whole. More material, for example, on queer perspectives (some of which are present in the recent volume Russian Performances: Word, Object, Action edited by. Julie A. Buckler, Julie A. Cassiday, and Boris Wolfson (2018), or the study of decoloniality exemplified in the work of Madina Tlostanova, would have been welcome. Also conspicuous in its absence are works reflecting on Eastern European production that engages with environmental issues and the current climate emergency—despite the fact that Eastern European art collectives are often closely connected to climate activism, or that ecocinema from Eastern Europe is emerging as an important field of contemporary scholarship, or indeed that the Non-Aligned Movement is being look to as a model for a new global alliance for climate action. Perhaps this remains for a future volume. In the meantime, there is no doubt that students, scholars, artists, activists, and art enthusiasts alike will find much to keep them occupied in this captivating and important volume.