Uzbek Elegy: The Films of Ali Khamraev

Along with Andrey Konchalovsky and Otar Iosseliani, Ali Irgashaliyevich Khamraev (in Uzbek, Ali Hamroev; b. 1937) is one of the great survivors of Soviet New Wave Cinema. Since 1964, Khamraev has been active in numerous genres, from the Romantic Comedy to the Political Drama, and from the Western to the Art-cinema Parable, to the TV mini-series. The son of a Tadjik man and a Ukrainian woman, he typified Soviet poly-nationalism, working for studios across Central Asia and Russia, from Tadjikistan to Moscow. Since the fall of the Soviet Union he has also lived for a time in Italy. Kent Jones has called him “far and away the most flamboyant director in the entire region [of Central Asia] and an artist of rock-solid humanism and amazing expressive power.”(Kent Jones, “Lone Wolves at the Door of History,” Film Comment vol. 39, no. 3, May/June 2003, pp. 54-55.)

Jones also celebrates Khamraev’s poly-stylism, calling him “one of those rare talents like Welles or Godard or Scorsese whose love for the medium is so intense that his best films burst with criss-crossing energies and insights, like a fireworks display.”(Ibid., p. 57.) However Khamraev’s “kidinacandystore” attitude toward cinematic history could also be attributed to a lack of a firm aestheticfulcrum. His eclecticism often leaves his films seeming derivative. A recent retrospective of eight of Khamraev’s features (from 1966 to 1998), distributed by Seagull Films and shown (among other venues) at the Gene Siskel Film Center, School of the Art Institute of Chicago, has provided a rare chance to assess Khamraev’s repertoire, as well as re-examine the aesthetic exchange among Soviet filmmakers and the International New Wave.

The Story of an “Unveiling”

After graduating in 1961 from the All-Union State Institute of Cinematography (known by its Russian acronym VGIK), where he studied under Grigorii Roshal’, Khamraev emerged in 1964 with the film Yor-Yor (the title is an Uzbek wedding song), a lyrical comedy in color, which was dubbed into Russian and released as Where Are You, My Zul’fiia? (Gde Ty, Moia Zul’fiia?). (At the time of writing it is available on YouTube in both Uzbek and Russian versions.) Under pressure from his father to find a bride, the protagonist of the film falls in love with a young singer he happens to glimpse on a television set in a shop window. She is identified to him by other onlookers, enchanted as much by the technology as by the voice, as Zul’fiia Rakhimova. The protagonist then bluffs his way into the television studio, blunders onto the soundstage where a live variety program is in progress, and inadvertently broadcasts his profession of love to the entire audience. Evidently sharing his immediate attraction Zul’fiia writes him a letter, but amidst his family’s move to a new apartment he loses the envelope with her address. After a series of misadventures, many of which involve musical performance, our young protagonist recovers his beloved’s address, but her home has disappeared. However, when his family moves into the new highrise building, he discovers Zul’fiia watering the flowers on the balcony next to his own. As in the narrative, so in the style, Yor-Yor shows Khamraev to have pre-occupied from the beginning with his search for an autochthonous Uzbek (and sometimes pan-Central Asian) modernity, gladly drawing on models from Moscow to Bombay.

In subsequent films, this commitment became focused as a dominant metaphor, that of the “unveiling” of modern Uzbek individuals. White, White Storks (Belye, Belye Aisty, 1966) shows Khamraev (in black-and-white) drawing on Ozu and Italian Neo-Realism in search of a distinct Central Asian style. We see a sleepy Uzbek village, where the only person in motion appears to be the officious postman. Malika (Sairam Isaeva/Sayram Isoyeva) is an abused wife who finds support in the quiet Kayum (Bolot Beishenaliev). Their mutual sympathy angers her husband and shames her father. When Kayum disappears, Malika suspects the worst, but he soon returns to claim her. It remains to be seen whether she will accept him after his cowardice. The point of this melodrama is never in doubt, as the film opens with a spread of newspaper headlines, such as “Fight Survivals of the Past.” Nor is its claim to documentary veracity at issue; a voiceover declares “We have invented hardly a single thing in this entire story.” The credits include among the actors the residents of a village who participated in the shoot, which augments the sense of documentary veracity.

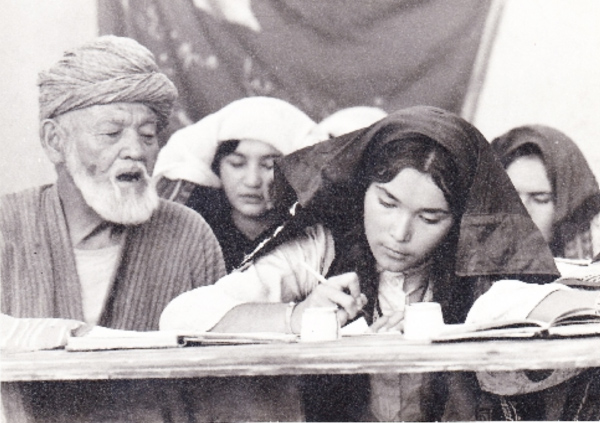

The liberation of Uzbek women is also the main subject of Without Fear (Bez Strakha, 1972), set in a village 60km from Tashkent in 1927, in the midst of campaigns for the redistribution of land and the “unveiling” of women. The Red Army commissar (Jakub Akhmedov) and his lieutenant (Bolot Beishenaliev) face a populace of reluctant women and openly hostile men. The only volunteer is a young girl (Dilorom Kambarova) who is shamed and killed. The result is a massacre of the Reds, but over their corpses the women begin ripping off their veils. This rousing finale occurs just as cars from the Tashkent-Bukhara road race roar into view. As is clearly and repeatedly enunciated in the film, the forces of tradition are helpless before the pressure of history, for better or for worse.

The liberation of Uzbek women is also the main subject of Without Fear (Bez Strakha, 1972), set in a village 60km from Tashkent in 1927, in the midst of campaigns for the redistribution of land and the “unveiling” of women. The Red Army commissar (Jakub Akhmedov) and his lieutenant (Bolot Beishenaliev) face a populace of reluctant women and openly hostile men. The only volunteer is a young girl (Dilorom Kambarova) who is shamed and killed. The result is a massacre of the Reds, but over their corpses the women begin ripping off their veils. This rousing finale occurs just as cars from the Tashkent-Bukhara road race roar into view. As is clearly and repeatedly enunciated in the film, the forces of tradition are helpless before the pressure of history, for better or for worse.

A later political drama (unfortunately absent from the retrospective, but available on YouTube), is the joint Soviet-Afghan production Hot Summer in Kabul (1983). Set in 1978, before the Soviet invasion, the film follows an elderly Russian doctor Vladimir Fedorov (Oleg Zhakov, in his final role) on a lecture trip to a young Afghan Republic, embroiled in what his host and former student Pavel (Nikolai Olialin) calls an “undeclared war.” Shot by Iurii Klimenko, with whom Khamraev frequently worked, the film maintains a documentary feel, even as it veers towards a thriller, specifically when the doctor’s helicopter is forced to land amidst an attack by the “dushmany,” as the Russians call the Mujahadeen. Khamraev dutifully drives home the ideological lesson: Afghans face a choice between friendly assistance and terrorism,without compromising a sense of raw authenticity (though Peter Rollberg dismisses the film as “political demagoguery”)(Peter Rollberg, Historical Dictionary of Russian and Soviet Cinema (Lanham, Md.: Scarecrow Press, 2009) p. 336.). The intervening thirty-odd years of Afghan history only make the brief cameos of Afghan subjects all the more compelling.

In the early 1970s his search for a style brought Khamraev to embark on two parallel, but very different series of films: Central Asian Westerns (or “Easterns,” as they are sometimes known) and Art films. Seventh Bullet (Sed’maia Pulia, 1972) is the first of Khamraev’s Uzbek Westerns in the Seagull retrospective, and is co-scripted by Fridrikh Gorenshtein and Andron Konchalovskii. In the film, the warlord Khairulla raids a Red Army stronghold and defeats a detachment of Red guards, but their commander Maksumov (Suimenkul Chokmorov) does not give up. He then courageously infiltrates the warlord’s fortress, betting on the loyalty of his men. A central role is played by Khairulla’s young bride (Dilorom Kambarova), who (like the soldiers) aids the cause of the Reds, although more out of personal affection for Maksumov than for any overt ideological commitment. Seventh Bullet was followed in 1979 by The Bodyguard (Telokhranitel’), in which a Red Army officer (Aleksandr Kaidanovskii) escorts a sultan (Anatolii Solonitsyn) and his young bride (Gul’buston Tashbaeva) across the desert. The sultan’s questionable motivation underscores the film’s shaky politics, and any discussion of women’s liberation or other social issues is a mere afterthought. Both Westerns feature distinctive soundtracks, cool jazz in the case of Seventh Bullet, Eduard Artem’ev’s synthesizers in the case of The Bodyguard, but while they veer towards self-parody, Khamraev’s films never reach the endearing humor of Vladimir Motyl’’s White Sun of the Desert (Beloe solntse pustyni, 1970), the classic of the genre.

In the early 1970s his search for a style brought Khamraev to embark on two parallel, but very different series of films: Central Asian Westerns (or “Easterns,” as they are sometimes known) and Art films. Seventh Bullet (Sed’maia Pulia, 1972) is the first of Khamraev’s Uzbek Westerns in the Seagull retrospective, and is co-scripted by Fridrikh Gorenshtein and Andron Konchalovskii. In the film, the warlord Khairulla raids a Red Army stronghold and defeats a detachment of Red guards, but their commander Maksumov (Suimenkul Chokmorov) does not give up. He then courageously infiltrates the warlord’s fortress, betting on the loyalty of his men. A central role is played by Khairulla’s young bride (Dilorom Kambarova), who (like the soldiers) aids the cause of the Reds, although more out of personal affection for Maksumov than for any overt ideological commitment. Seventh Bullet was followed in 1979 by The Bodyguard (Telokhranitel’), in which a Red Army officer (Aleksandr Kaidanovskii) escorts a sultan (Anatolii Solonitsyn) and his young bride (Gul’buston Tashbaeva) across the desert. The sultan’s questionable motivation underscores the film’s shaky politics, and any discussion of women’s liberation or other social issues is a mere afterthought. Both Westerns feature distinctive soundtracks, cool jazz in the case of Seventh Bullet, Eduard Artem’ev’s synthesizers in the case of The Bodyguard, but while they veer towards self-parody, Khamraev’s films never reach the endearing humor of Vladimir Motyl’’s White Sun of the Desert (Beloe solntse pustyni, 1970), the classic of the genre.

At the very same time that Khamraev was exploiting the popular appeal of the Western, he was also making a clear case for inclusion amongst the Soviet Union’s recognized auteurs, enabled by Iurii Klimenko. Khamraev and Klimenko’s collaborations always remain inseparable from specific models in Soviet cinema. In Man Follows Birds (Chelovek Ukhodit Za Ptitsami, 1975), Khamraev turns to the archaism of Tarkovskii’s Andrei Rublev (1966/1969), Paradzhanov’s Shadows of Forgotten Ancestors (1964), and Color of Pomegranates (1968). A boy Farukh (Dzhanik Faiziev) catches sight of a beautiful girl Gul’cha (Dilorom Kambarova), who floats by elusively like an ethereal apparition. The film is an extended visual study of a poem that is repeated several times in the film, “The almond-trees have blossomed in the mountains… And the snow of my tears is melting”, perhaps it is the story of the poem’s composition. For Kent Jones, it differs from Paradzhanov in its “more boyishly melodramatic undertone,”(Jones, “Lone Wolves at the Door of History,” p. 57.) but the differences are less conspicuous than the similarities. Entire shots, lines of dialogue, and interludes of baroque music seem lifted directly from Tarkovskii and Paradzhanov. Ultimately, the film says more about the power of their influence on Soviet cinema than about the characters or cultures it presents.

At the very same time that Khamraev was exploiting the popular appeal of the Western, he was also making a clear case for inclusion amongst the Soviet Union’s recognized auteurs, enabled by Iurii Klimenko. Khamraev and Klimenko’s collaborations always remain inseparable from specific models in Soviet cinema. In Man Follows Birds (Chelovek Ukhodit Za Ptitsami, 1975), Khamraev turns to the archaism of Tarkovskii’s Andrei Rublev (1966/1969), Paradzhanov’s Shadows of Forgotten Ancestors (1964), and Color of Pomegranates (1968). A boy Farukh (Dzhanik Faiziev) catches sight of a beautiful girl Gul’cha (Dilorom Kambarova), who floats by elusively like an ethereal apparition. The film is an extended visual study of a poem that is repeated several times in the film, “The almond-trees have blossomed in the mountains… And the snow of my tears is melting”, perhaps it is the story of the poem’s composition. For Kent Jones, it differs from Paradzhanov in its “more boyishly melodramatic undertone,”(Jones, “Lone Wolves at the Door of History,” p. 57.) but the differences are less conspicuous than the similarities. Entire shots, lines of dialogue, and interludes of baroque music seem lifted directly from Tarkovskii and Paradzhanov. Ultimately, the film says more about the power of their influence on Soviet cinema than about the characters or cultures it presents.

Tarkovskii’s presence becomes increasingly oppressive in Khamraev’s next two films Triptych (Triptikh, 1979) and I Remember You (Ia tebia pomniu, 1985). After a brief prologue, which shows the retirement of an old teacher, Triptych follows his memories back to 1946. It focuses on a young Khalima (Dilorom Kambarova) who has been abandoned by her husband, whom she then finds accidentally at a building site. Two people she comes into contact with, her sons’ teacher (Shavkat Abdusalamov) and a bureaucrat Sanibor (Gul’buston Tashbaeva), become romantically involved with her though perhaps only in their imaginations. Khalima ends up building herself a house in the dead of winter. Fragmentary conversations and enigmatic framings (including generous double and triple exposures) allow the viewer to study this situation in light of the elderly teacher’s opening declaration, “Our life was hard but honest.” (Unsurprisingly, Tarkovskii held Triptych in high regard.(Shavkat Abdulasamov, [Memoir about Aleksandr Kaidanovskii], in Aleksandr Kaidanovskii: V vospominaniiakh i fotografiiakh (Moscow: Iskusstvo, 2002) pp. 121-30: 122; first published in Kinovedcheskie zapiski no. 47, 2000, pp. 314-321.))

Tarkovskii’s presence becomes increasingly oppressive in Khamraev’s next two films Triptych (Triptikh, 1979) and I Remember You (Ia tebia pomniu, 1985). After a brief prologue, which shows the retirement of an old teacher, Triptych follows his memories back to 1946. It focuses on a young Khalima (Dilorom Kambarova) who has been abandoned by her husband, whom she then finds accidentally at a building site. Two people she comes into contact with, her sons’ teacher (Shavkat Abdusalamov) and a bureaucrat Sanibor (Gul’buston Tashbaeva), become romantically involved with her though perhaps only in their imaginations. Khalima ends up building herself a house in the dead of winter. Fragmentary conversations and enigmatic framings (including generous double and triple exposures) allow the viewer to study this situation in light of the elderly teacher’s opening declaration, “Our life was hard but honest.” (Unsurprisingly, Tarkovskii held Triptych in high regard.(Shavkat Abdulasamov, [Memoir about Aleksandr Kaidanovskii], in Aleksandr Kaidanovskii: V vospominaniiakh i fotografiiakh (Moscow: Iskusstvo, 2002) pp. 121-30: 122; first published in Kinovedcheskie zapiski no. 47, 2000, pp. 314-321.))

If Triptych is an elegiac homage to his parents’ generation, then I Remember You is much more directly autobiographical. The protagonist Kim (Viacheslav Leonidovich Bogachov) is sent by his dying mother, a Ukrainian woman, to Asia to find the grave of his Uzbek father, outside the Russian town of Viaz’ma. He is shown the site where his father(a partisan) was buried, along with several others. On the return journey he falls in love with a beautiful musician (Gul’buston Tashbaeva). In the meantime, his sister has visitedAsia and together they revel in memories and fantasies that distend the spaces of Samarkand into a dream-world. The straightforward plot is given depth by means of enigmatic set pieces, from ballet dancers who interrupt their pas-de-deux to plead “Give the woman some medicine,” to scenes from Kim’s childhood as recorded in his memory. The film ends with a shot of the director packing up his camera and leaving the studio.

If Triptych is an elegiac homage to his parents’ generation, then I Remember You is much more directly autobiographical. The protagonist Kim (Viacheslav Leonidovich Bogachov) is sent by his dying mother, a Ukrainian woman, to Asia to find the grave of his Uzbek father, outside the Russian town of Viaz’ma. He is shown the site where his father(a partisan) was buried, along with several others. On the return journey he falls in love with a beautiful musician (Gul’buston Tashbaeva). In the meantime, his sister has visitedAsia and together they revel in memories and fantasies that distend the spaces of Samarkand into a dream-world. The straightforward plot is given depth by means of enigmatic set pieces, from ballet dancers who interrupt their pas-de-deux to plead “Give the woman some medicine,” to scenes from Kim’s childhood as recorded in his memory. The film ends with a shot of the director packing up his camera and leaving the studio.

Despite the conspicuous borrowings from Mirror and Stalker, from a hand held before a flame to Kim’s mother’s monologue into the camera, I Remember You is Khamraev’s supreme achievement. All his stylistic influences are finally transformed by the powerful and unmistakably individual tone. For Khamraev the war is, like pre-revolutionary tradition, an oppressive legacy. Despite his desire to liberate himself and his generation from the heavy weight of history, it continues to exert moral claims on him. I Remember You is also the only one of Khamraev’s films that directly takes on the relationship between Uzbek and Russian cultural traditions. The scene during the New Year’s party, on the train, clashes jarringly with the dominant tone, and is a marvelous piece of improvisation. It portrays the master artist at his peak, aware of being limited by his historical moment, yet confident in his ability to transcend it.

Since the fall of the Soviet Union, Khamraev has been sporadically spotted on the international festival circuit. His recent work was presented in the retrospective by the film Bo Ba Bu (1998), a French-Italian co-production. Two desert herders discover a bedraggled fashion model (Arielle Dombasle) amidst the wreckage of an airplane. They wash her and then clothe her in rags. By means of gestures and grunts, the elder of the two (Abdrashid Abdrakhmanov) introduces them as Bu and Bo and suggests that she be called Ba. They show her around, take her to a dogfight, rape her and fight over her. She in turn teaches them to use eating utensils. She establishes a sympathetic relationship with the younger of the two, and their sex appears to become consensual. Conflict between Bo and Bu leads to the elder selling Ba to a whorehouse in Khiva, but soon she is back at home with them, chained among the livestock.

Since the fall of the Soviet Union, Khamraev has been sporadically spotted on the international festival circuit. His recent work was presented in the retrospective by the film Bo Ba Bu (1998), a French-Italian co-production. Two desert herders discover a bedraggled fashion model (Arielle Dombasle) amidst the wreckage of an airplane. They wash her and then clothe her in rags. By means of gestures and grunts, the elder of the two (Abdrashid Abdrakhmanov) introduces them as Bu and Bo and suggests that she be called Ba. They show her around, take her to a dogfight, rape her and fight over her. She in turn teaches them to use eating utensils. She establishes a sympathetic relationship with the younger of the two, and their sex appears to become consensual. Conflict between Bo and Bu leads to the elder selling Ba to a whorehouse in Khiva, but soon she is back at home with them, chained among the livestock.

As allegory, the film is as heavy-handed as Andrei Zviagintsev’s Banishment (Izgnanie, 2007) or Sergei Loznitskii’s My Joy (Schast’e moe, 2010), but even more vacuous than them. However, it could be taken as an updated version of Khamraev’s earlier analyses of gender relations in Central Asia. In one taped interview, (on YouTube) Khamraev makes a point of criticizing Gul’shad Omarova’s Shizo (2004) for denigrating Kazakh culture in its effort to fulfill the “sotszakaz” of Western audiences, i.e. to be pandering to Western stereotypes of the region. However the elimination of dialogue appears calculated to make the film easily exportable. Given the air traffic and the military officer who twice comes to ogle at Ba and steal the men’s livestock, the film could be commenting on the ways in which a now dominant Western culture is leading to the re-objectification of women as sex objects (and a new colonization of Central Asia). Yet, none of these possible explanations is ultimately cohesive, and all of them are liable to end up seeming like feeble excuses for the camera’s intent examinations of Dombasle’s exposed flesh. If Bo Ba Bu is Khamraev’s unveiling of a new, post-Soviet Uzbek modernity, it would appear to register nothing beyond the continuing crisis of identity in the region’s cinema.

The Soviet Exchange

In her review of White, White Storks, T. Khlopliankina began by declaring: “Yes, this is today’s cinema – in the rhythm, the camera work, the music of R. Vil’danov, which does not try to comment on the story but, as if for a moment, removes us from the chain of immediate events and carries us far and high, enriching our perception.”(T. Khlopliankina, Sovetskii ekran no. 19 (1966). Accessed on 6 March 2011 from: < http://www.kino-teatr.ru/kino/movie/sov/485/annot/>) Indeed, so many of Khamraev’s stylistic choices are recognizable from mainstream (i.e., Russian) contemporary Soviet cinema that one is tempted to classify his films as provincial imitations. Most of his films have clearly identifiable models. Yor-Yor follows close along Georgii Daneliia’s I Stroll around Moscow (Ia Guliaiu Po Moskve, 1962). The white storks that appear in the closing sequences are the most obvious homage to the cinema style of the Soviet Thaw, which was typified by the camera work of Sergei Urusevskii in Mikhail Kalatozov’s The Cranes Are Flying (1957). The notion of using genuine villagers is probably taken from Asia Kliachina by Andron Konchalovskii (Istoriia Asi Kliachinoi…, 1967), with whom Khamraev later collaborated. When he strays from models, one might think, Khamraev loses his way, as he seems to do in Bo Ba Bu.

However, Khamraev does display elements of a distinct individual style. Each of his films (save the Westerns) includes at least one extended conversation in which the dialogue is replaced by music, frequently that of Rumil’ Vil’danov. There is an easy slippage between waking reality and dreamscapes, often shot with simple special effects. Most of Khamraev’s films are pervaded by an exuberant humor that at times, especially in the Westerns, verges on slapstick. Perhaps most interestingly, Khamraev’s films retain elements of distinctive performance styles, from the acting of the elders in Without Fear to the New Year’s celebration in I Remember You, which might represent original Uzbek developments, perhaps under the influence of Bollywood. If Khamraev’s images are rarely as stunning as those of his peers, one notes that his financial and technical resources are much more limited; for instance, his films were all shot on inferior Soviet stock.

However, Khamraev does display elements of a distinct individual style. Each of his films (save the Westerns) includes at least one extended conversation in which the dialogue is replaced by music, frequently that of Rumil’ Vil’danov. There is an easy slippage between waking reality and dreamscapes, often shot with simple special effects. Most of Khamraev’s films are pervaded by an exuberant humor that at times, especially in the Westerns, verges on slapstick. Perhaps most interestingly, Khamraev’s films retain elements of distinctive performance styles, from the acting of the elders in Without Fear to the New Year’s celebration in I Remember You, which might represent original Uzbek developments, perhaps under the influence of Bollywood. If Khamraev’s images are rarely as stunning as those of his peers, one notes that his financial and technical resources are much more limited; for instance, his films were all shot on inferior Soviet stock.

Most fascinating, however, are the reminders that Khamraev’s relationship with his more mainstream counterparts cannot be viewed as one-way traffic. When viewed alongside the films of his contemporaries, Khamraev’s cinema clearly instantiates the intense exchange that occurred between studios and national cinema traditions in the USSR. The Central Asian studios provided a willing market for screenplays by Russian authors. In addition to his work with Khamraev, Konchalovskii contributed to the screenplay for Tolomush Okeev’s Fierce One (Liutyi, 1973). Following Konchalovskii’s lead, Tarkovskii contributed the screenplay to Z. Sabitov’s Beware, Snakes! (Beregis’ zmei, 1979). Tarkovskii’s diary details his work with Aleksandr Misharin on the screenplay of a Western intended for Khamraev.(Andrei Tarkovskii, Martirolog: Dnevniki 1970-1986 (n.l.: Mezhdunarodnyi institut imeni Andreia Tarkovskogo, 2008) pp. 99, 105, 110, 125, 138, 14.) The exchange also involved actors like the Kyrghyz Bolot Beishenaliev, who had played a major role in Konchalovskii’s First Teacher (Pervyi uchitel’, 1965) and Tarkovskii’s Andrei Rublev (1966/1969), before Khamraev cast him in several of his own films.

Khamraev served as a conduit by which Central Asia acquired palpable aesthetic value in Russian films. For instance, Seventh Bullet appears to have exerted a clear influence on Nikita Mikhalkov’s At Home Among Strangers (1974). A key figure in this aesthetic exchange is Shavkat Abdusalamov, who served as set designer on several of Khamraev’s films (from White, White Storks to Hot Summer in Kabul) and acted in The Bodyguard and Triptych. He also worked with Tarkovskii on the set design of Stalker, and in a memoir highlights the tantalizing connections between Khamraev’s Bodyguard and Tarkovskii’s Stalker (1980). Both films were scored by Eduard Artem’ev, using his innovative synthesizer. Sharing most of their cast, both films show Aleksandr Kaidanovskii leading an expedition through desolate territory, on what may be a fool’s quest. In both cases, he is faced with the problem of conveying Anatolii Solonitsyn. Nikolai Grin’ko, the third member of the group in Stalker, plays a Red Army officer at the beginning of The Bodyguard. (Disconcertingly, all three were dubbed by other actors, and to complete the jarring effect Abdusalamov’s voice was supplied by Oleg Iankovskii, star of Tarkovskii’s next feature Nostalgia [1982). The films could have been together bound even more closely. Stalker was originally slated to be shot in Isfara, Tadjikistan, where parts of The Bodyguard were filmed (the plan was allegedly abandoned after an earthquake hit the area). Igor’ Maiboroda’s 2009 documentary Rerberg i Tarkovskii: Obratnaia storona Stalkera includes photographs of Khamraev and Tarkovskii scouting locations for Stalker. Shavkat Abdusalamov has written that Khamraev purposefully made The Bodyguard as “a kind of variation on Stalker with Central Asian material,”(Shavkat Abdulasamov, [Memoir about Aleksandr Kaidanovskii], pp. 122; 125-6.) but the overlapping chronology of the two projects suggests that they were developed in tandem.

The intensity of this mutual aesthetic exchange between Khamraev and Russian directors in the 1970’s forces one to reframe the question of Khamraev’s legacy in post-Soviet cinema of the region. Most suggestive are the fleeting similarities in tone and technique with the cinema of Aleksandr Sokurov, another accomplished polystylist who is not afraid of spectacular failures. These similarities are strongest in Days of Eclipse (Dni zatmeniia, 1988), which was shot in Turkmenistan. He later returned to the region for his 1994 documentary Spiritual Voices (Dukhovnye Golosa). Whether or not Sokurov knew (let alone admired) Khamraev’s films, he provides a name for the genre, the social elegy, which in retrospect, Khamraev did as much as anyone to establish in late and post-Soviet cinema.

Robert Bird, of The University of Chicago, is Associate Professor in the Department of Slavic Languages and Literatures, Cinema and Media Studies, and the College; Associate Faculty in the Divinity School. His main area of interest is the aesthetic practice and theory of Russian modernism.

Robert Bird, of The University of Chicago, is Associate Professor in the Department of Slavic Languages and Literatures, Cinema and Media Studies, and the College; Associate Faculty in the Divinity School. His main area of interest is the aesthetic practice and theory of Russian modernism.