Interview with Artpool Cofounder Júlia Klaniczay

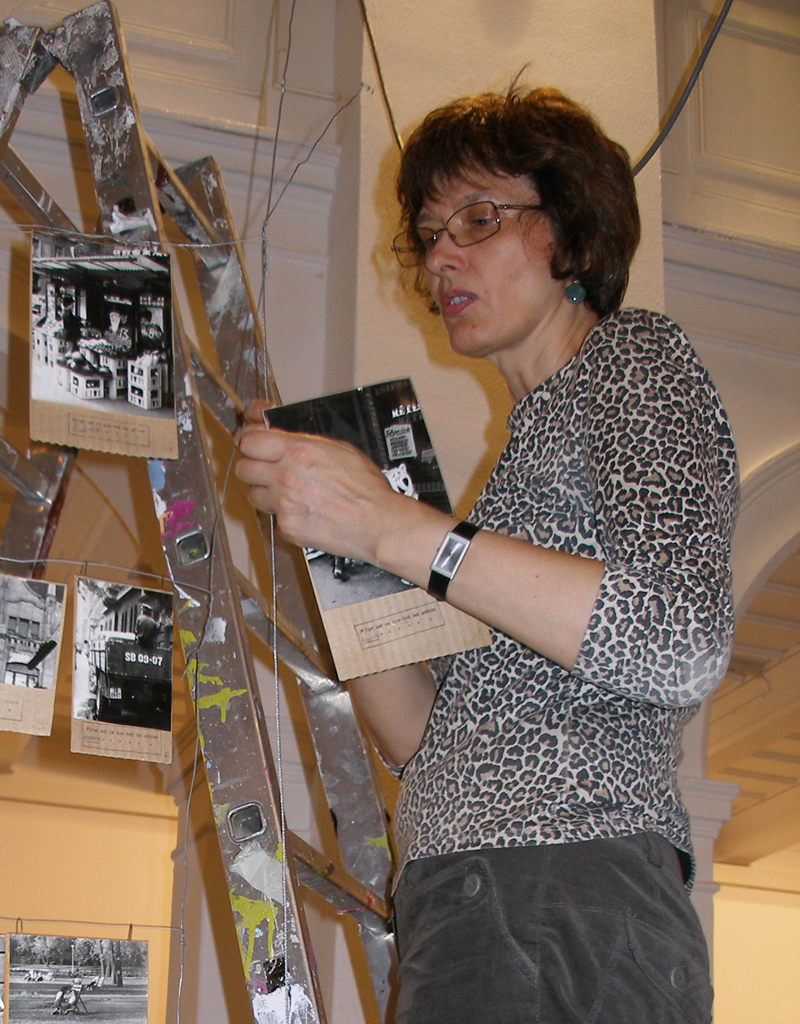

In 1979, Júlia Klaniczay co founded Artpool together with the artist György Galántai. From 1976 onward she was a participant of many art projects concieved by Galántai within the framework of Artpool. Klaniczay is in charge of Artpool’s archives and publications. From 1977 to 1992 she was also the editor-in-chief at Akadémiai Kiadó, the publishing house of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences. Klaniczay has authored several articles and seved as a researcher for the alternative art scenes of the 1970s and 1980s. Since 1992 she has been the director of the public nonprofit institution Artpool Art Research Center in Budapest.

György Galántai and Júlia Klaniczay have been actively involved in the Hungarian cultural scene, since the late 1960s and the 1970s, respectively,.Galántai’s name has often been associated with the Balatonboglár Chapel, a space he rented and transformed into a studio, and which became the most important space for experimentation for the Hungarian neo-avant-garde between 1970 and 1973. In addition to his wide-ranging artistic practice and participation in numerous exhibitions, Galántai, alone or in collaboration with Júlia Klaniczay (from 1976), was very active in setting up initiatives and exchanges among the artistic community. Exhibitions such as Everybody with Anybody (1982) and Hungary Can Be Yours (1984), both at the Young Artists’ Club in Budapest, or World Art Post (1982) at the Fészek Klub, also in Budapest, gave visibility to practices such as mail art, stamp art, and collective artistic proposals. Other initiatives emanating from the Galántai duo included presentations and debates, publications (such the mail art newsletter Pool Window, and later, the Artpool Letter, also titled Aktuális Levél (AL), considered one of the first artistic samizdat publications in Hungary, issued between 1983 and 1985), and even the radio program Artpool Radio, presenting a selection of sound creations through tape recordings.

In 1979, the couple started the Artpool Archive as an alternative institution collecting information on national and international artists, and welcoming contributions from any geographic origin, discipline, or type of production. The original source of works for this singular collection was a simple formula stamped on letters or invitations sent out within Hungary and abroad: “Please send information about your activity.” Due particularly to the Galántais’ involvement in the international Mail Art network, this simple request succeeded beyond their expectations, and after more than three decades of continuous activity and its conversion from an illegal organization into a recognized cultural foundation (the Budapest-based Artpool Art Research Centre, inaugurated in 1992), Artpool’s “active archive” has become one of the most important sites for the conservation and consultation of material concerning non-conventional forms of art from the 1970s onwards, not only from Hungary and Eastern Europe, but also from Latin-America, Western Europe, and North America.

This conversation with Júlia Klaniczay took place at the Artpool Archive in Budapest, in January 2011. It focuses on the exhibition Hungary Can Be Yours!/International Hungary (Magyarország a tiéd lehet!/ Nemzetközi Magyarország). Organized in January 1984 by György Galántai at the Young Artists’ Club in Budapest (often referred as “FMK” for “Fiatal M?vészek Klubja”), the exhibition brought together works by Hungarian and international artists around the topic “Hungary.” Right before its opening, it was censored by the Communist authorities for displaying works which failed to conform to the regime’s cultural policies. Following the political changes in Hungary, Hungary Can Be Yours was recreated for the first time in December 1989, with the aim of showing the censored works and investigating the process that had led to the banning of the exhibition. In the year 2000, further restagings took place, this time motivated by the opening of the State Security Archives and the unearthing of a series of reports concerning Galántai’s activities. Some of the reports referred to this particular exhibition.

The exhibition as well as its banning and its subsequent recreations have been extensively documented; not only by the organizers themselves, also by State institutions and apparatuses of control and by the Hungarian and Western media. The existence of such heterogeneous sources is precisely what makes it an interesting point of departure from which to examine the social uses of information and its specificities in the context of 1980s in Hungary.

One of the intentions with the following interview was to shed light on the interconnectedness of artistic and political practices among what the Hungarian sociologist Elemér Hankiss has called the “second society” or the “second public sphere”.(Hankiss’s definition of a “second society” refers to a “sphere of social existence where a second configuration of organizational principles, a second paradigm, was at work until the mid-1980s,” in parallel or sometimes even juxtaposed to the first society whose rules reflected the Communist party’s line. Elemér Hankiss, East European Alternatives (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1990) p. 104.) It is in fact important to point out the inconsistencies involved in separating radically the activities of the “political” democratic opposition, on the one hand, and those of the cultural scene whose role in the transformation of Hungarian society has often been played down, on the other. It is also essential to consider the relationship between the “original” event of 1984 and its “afterlives” in 1989 and the 2000s, especially in the light of the search for truth and justice that characterized almost all societies of the former Eastern bloc in the post-Communist era.

Juliane Debeusscher: I would like to focus this conversation on the exhibition Hungary Can Be Yours, organized by György Galántai at the Young Artists’ Club in Budapest in 1984, and banned by the authorities just before its opening. Could you introduce the main idea of the exhibition, and give some details about the first steps in its organization? If I’m not mistaken, everything started while Galántai was preparing a special issue of the magazine Commonpress, dedicated to Hungary?

Júlia Klaniczay: That’s right. Commonpress was an international magazine project, anyone interested could take part in it by writing to its main editor, the Polish artist Pawe? Petasz, and ask to become the editor of one issue. György decided to apply after seeing Adriano Spatola’s issue, which was dedicated to Italy. We liked very much the reactions and thought it could be interesting to ask the international community to give its views on Hungary. We were very much devoted to the spirit of our country, and we thought that, although one could hardly be very happy about our situation, it was really up to us to remember that the country belongs to us. These were important topics during the 1970’s and the 1980’s: everybody was wondering if it was better to run away or stay; if you were responsible for trying to save what you could; and do something so the country wouldn’t disappear into this gray, annoying Communist culture.

JD: Does the title refer to the slogan from the era of Stalinist Hungarian leader Mátyás Rákosi, “Hungary is yours,” or was it interpreted in this way only later?

JK: The Rákosi slogan was: “The country is yours, you build it for yourself.”(Mátyás Rákosi (1892-1971) was the Stalinist leader of Hungary between 1945 and 1956.) The way people try to understand the Bible, explain every phrase and take out what is relevant for them, so we also tried to understand these slogans, preserving those that could be applied to our situation and become positive for us. I remember for example that while György was running the Balatonboglár Chapel, he argued with the police by quoting official discourses and Communist slogans. So yes, I can well imagine that this refrain was behind the exhibition’s title.

JD: The Commonpress issue had also another title: International Hungary.

JK: There was a double title: Hungary Can Be Yours and International Hungary. We thought Hungary Can Be Yours could be for the Hungarians, and the other for the international community.

JD: What about the call for participation? Did you send invitation letters to your contacts from the Mail Art network?

JK: Yes, there were around a thousand contacts. The call was open to everyone. It was also announced in several publications. While we were collecting contributions for Commonpress, György met the artistic director of Budapest’s Young Artists’ Club, Antal Vásárhelyi, who offered him to do an exhibition with this material. I was not convinced it was a good idea. The Commonpress issue was not a political thing, but it was clear that the topic “Hungary” was in itself enough to see political intentions behind it. We sent out the exhibition announcement again, in particular for Hungarian artists who could send bigger works and not only poster-sized ones. We received new works, important and interesting ones. That’s how it started.

JD: Were the works initially checked by the police?

JK: No, they were directly brought to us. Only Antal Vásárhelyi, who was also participating, gave us his work directly at the Young Artists’ Club.

JD: Could you describe the process leading up to the banning of the exhibition, and the role of the official committee in this operation?

JK: At that time, according to the law, every exhibition had to be censored, that is to say controlled before its opening. In the 1980s, it became a very formal operation; generally, the committee came to see the exhibition just before the opening. I think our last exhibition to be checked a long time before was the artists’ stamps exhibition in 1982 [World Art Post, at the Fészek Klub]. The authorities had been watching us for months in order to understand what we were doing and what kind of works we were collecting.

In 1984, this procedure had turned to be very formal, and the jury came only the day of the opening. There was a delegate member of Budapest’s Visual Arts Directorate (Budapesti Képz?m?vészeti Igazgatóság). We were asked to name the jury, so György put forward the names of two artist colleagues, András Baranyai and Ádám Kéri. However, the director of the Club had been informed the day before by the authorities that the exhibition was to be banned. The members of the jury only learnt this when they arrived in the morning and they decided to ratify the banning.

The director had the right to keep exhibitions without authorization during three days, because the Young Artists’ Club was not a public place but a professional circle, open only to its members. Furthermore, thousands of invitations to the opening had already been sent and he didn’t want to have a scandal. As a consequence, the exhibition remained in place for three days and the opening took place. The doors were closed, but anyone coming with an invitation was let in.

JD: Why do you think the jury banned the entire exhibition and not only a few works, as was the usual practice at the time? Wouldn’t it have been easier to censor only the problematic works? Perhaps they were instructed to act in this way…

JK: That’s what I think. I think they didn’t have a choice, but these instructions were probably given on the spot. Ádám Kéri himself had a work in the exhibition. I think the jury had several options. They could have said “alright, this exhibition has to be banned, but we won’t sign anything. Why should there be a jury, if the ban has already been decided?” In this way, their signature and names wouldn’t have appeared on the document. In 1989, when we repeated the exhibition and made public the document with which the ban was enacted and which included their signatures, they felt very much offended.(The document mentioned here is the official document that bans the show with the backing of the jury. In 1989, the 1984 exhibition leaflet was reprinted and titled “Reconstruction of a Banned Exhibition” (Egy betiltott kiállítás rekonstrukciója). It included an exact copy of this document.) They did have the option of withdrawing only problematic works–maybe five of them–such as the map by the Inconnu group.(Among the works considered most problematic were those of Inconnu, a group of artists and activists from the city of Szolnok which moved to Budapest in the early 1980s. Inconnu (whose main members were Péter Bokros, Tamás Molnár and Robert Pálinkás) was frequently harassed by the police for its provocative and political works and for its connections with the Hungarian democratic opposition. The works exhibited in Hungary Can Be Yours referred explicitly to the taboo topic of Hungary’s colonization by the Soviet Union. For instance, they displayed a map of Hungary isolated in a red “sea” whose surface is filled with nails. Numerous other works in the exhibition were based on the reinterpretation of Hungary’s and Europe’s map. The presence of Inconnu is often seen as the main motive for the exhibition’s prohibition. For instance, the author of a Situation Report for Radio Free Europe observed that considering the presence of Inconnu, it “came as no surprise that the authorities disapproved of the art show and closed it.” (“Unorthodox Hungarian art exhibit closed”, 25 February1984, Open Society Archives, HU OSA 300-8-47, RFE/RL RI: Publications Department: Situation Reports, 1959-1989, Hungary, 1984, container n. 24.)

JD: How did the first restaging of the exhibition happen?

JK: In 1989, when the system changed, anyone who had done something wrong began to feel guilty, and tried to see how he could make it better. You can imagine that a lot of people were afraid of those towards whom they had acted very badly. One day, we received a phone call from the art director of the Young Artists Club. She proposed to Galántai to make an exhibition there. She was not the only one; Galántai got also a phone call from Balatonboglár, to ask if he wanted the Chapel back! Of course, this nice era lasted only one month or two. After the elections, everybody was glad to see that nothing was about to change: nobody would be tried, nothing would be given back… György said he accepted the YAC’s offer only if he could reconstruct Hungary Can Be Yours and print the catalogue. He also wanted to organize a roundtable discussion and invite those who had taken part in the 1984 ban of the show.(The whole roundtable was video-documented. It can be consulted in the Artpool archive, ref. n. 609, E 8906, E 8907.)

Some people didn’t come, they were upset with the fact that their names had been made public. The director of the Budapest Visual Arts Directorate at that time, Attila Zsigmond, did participate. I don’t understand why! He was convinced he had done his best to save the exhibition and help Galántai. This shows that people didn’t realize how much they were helping the Communist system, serving its aims. I didn’t like this debate, it was not constructive at all. We expected the censors to explain what had happened, and why. But we didn’t learn anything from this experience.

JD: So the facts have remained unknown until now?

JK: Not exactly; we received a few letters. For instance, a person from a ministry wrote to us explaining that when the exhibition was banned in 1984, they didn’t do anything to save Galántai. Why? Because at that time, they were already struggling to install Katalin Néray as the new director of M?csarnok (Kunsthalle) in Budapest. They wanted to modernize visual culture in Hungary a bit, and that was already a risky thing.

JD: What repercussions did the Hungary Can Be Yours incident have for your life?

JK: We just felt there were problems everywhere. Galántai lost all his jobs. At that time, he was renting a basement he had transformed into a studio. From one moment to another the local district authorities, which were responsible for rent, created a lot of problems. There were also letters that never arrived. We were very often controlled by the police, not only in the street but even in cafés or pubs.

JD: Were you allowed to travel abroad? Where did you travel during those years?

JK: In 1982 we went on a big tour through Europe. In 1983 Galántai received the Kassák prize which is awarded by Magyar M?hely, an organization based in Paris. The prize was supposed to be awarded in Vienna, but we were not allowed to travel there. In 1985 we received a DAAD grant but we could finally go to Germany only in 1988 when we finally obtained a passport and the visa. There were a lot of obstacles everywhere.

At that time, people didn’t believe the system was getting worse and worse from a cultural point of view because they could see nice exhibitions at M?csarnok. Artists who were not able to exhibit before, such as Imre Bak and Tamás Hence, were now given big shows. This was the nice face of the cultural policy: Hungarian artists were shown in the West, and people who were not directly involved in the art scene couldn’t know that this was happening just for the Western countries.

Only one positive thing happened at that time : in 1984, the Soros Foundation appeared in Hungary, and we were among the first to apply for financial support. We received money to maintain the archive and that was really important; it covered all our postage costs and also the production of the last AL’s (Artpool Letter).

Still in 1985, an art advisor for George Soros came to Hungary with the intention of working on the project for a Soros Art Centre. She came to us and liked very much the way we were organizing Artpool. She wanted to convince me to become the first art director of this Soros Art Centre, but she didn’t know anything about the political background. When she proposed my name as the director of the new center at the ministry, the deputy minister asked her whether she knew who I was: “[she’s] the wife of Galántai, who exhibited a Hungarian flag in a cage!”

The funniest thing is that this episode was the first proof that the report about Hungary Can be Yours that was shown on Hungarian state television had been seen by people from the Ministry and the Communist party. However, they had conflated two works! A Hungarian flag had been exhibited by the Inconnu group, and another work in the exhibition showed a cage. We joked about the fact that they invented a new work of art.

JD: As you just mentioned, a crew from Hungarian state television came to the opening and produced a report for the cultural program Studio. Some documents that surfaced in the 2000’s confirmed that they produced this report knowing that it would be censored.

JK: When the exhibition opened, György Baló, wo was responsible for the Studio program (Studio 84 at that time) had already been told by the authorities not to put the exhibition in the program.(The documents reporting these instructions are preserved in the Historical Archives of the Hungarian State Security. ÁBTL 3.1.5. O-19618/2, dated January 25, 1984 and February 9, 1984.) But a tv crew came to the show anyway and filmed all the exhibited works one by one. We don’t know what happened to this footage, but it is likely that the cassette was transmitted to the Party’s Central Committee.(Judging by my recent attempts to locate the tape, it seems to be conserved in the archives of the Hungarian State Television (Médiaszolgáltatás-támogató és Vagyonkezel? Alap). A fee has to be paid to see the tape.)

JD: The works exhibited in Hungary Can Be Yours are still preserved in the Artpool archive.

JK: Yes, we have kept all the works, and that’s how we could reconstruct the exhibition in 1989 and in the 2000s’.

JD: In 1989, you were finally able to publish the exhibition catalogue in the form of the Commonpress issue.

JK: We printed the 51st issue of Commonpress, which we hadn’t been able to complete in 1984. At the time we had planned a catalogue wrapped in a tourist prospectus on Hungary, but the person who had promised us this material became afraid and only few copies were issued. In 1989 it was printed in offset, practically with the same design. We have copies of both versions in the archive.

JD: What motivated the recreations of Hungary Can Be Yours in 2000 and 2001, and under what conditions did they take place?

JK: In 2000 we had access to the secret police reports. The first reconstruction showing the agents’ reports took place in our own space, Artpool P60. We didn’t really announce we had found them, we just said that the image of Hungary had changed very much, so it would be interesting to see the artists’ reflections on them one more time Very few people came.

In2001 the exhibition was then presented then at the Centralis Gallery at the Open Society Archives. This time around, we focused on the secret police reports. They were translated to English, and the whole show was built on the public presentation of these documents. The material was the same, but the announcement was different. Of course, it looked more attractive. This time a lot of people came, and the press mentioned it as well. This proves that what you do is not as important as the way you sell it.(The first reconstruction of Hungary Can Be Yours (including the police reports) took place from April 14 to 28, 2000, in the Artpool P60 art space. The second one took place at the Centralis Galeria of the Open Society Archives (Central European University) from October 2 to December 2, 2001 (http://www.osaarchivum.org/galeria/catalogue/2001/artpool/index.html).)

JD: It is clear that the intentions in the 2000s were very different from what they were in 1984 and 1989. This succession of restagings reflects a process that could be considered characteristic of the post-Communist period: on the one hand, the need to disclose hidden information, the until-then missing pieces of the puzzle; and the other, the will to re-establish the “truth”, or even to “bring justice”.

JK: In my opinion, these reconstructions with the secret police reports were very interesting because people could read for the first time what these agents had written. They could see the works together with their descriptions and measure to what extent those reports were full of hidden intentions.

The identity of the main agent was important as well, because he was a figure of the Hungarian avant-garde. He participated in the events at the Chapel Studio in Balatonboglár and since he was a very good friend of many people who participated in this cultural scene, it was really a shock for many of them. After this, some journalists tried to contact him. He had emigrated to New-Zealand and didn’t want to speak Hungarian at all. However, as a result of this interest, he sent us a letter in which he explained that he did this because he thought he was serving a good cause.

JD: His report on Hungary Can Be Yours is a very detailed one, reading it gives us the sense that he was quite familiar with the art scene of that time.(The report written by the agent whose code name was “Zoltán Pécsi” is available online in Hungarian and English (www.artpool.hu/Commonpress51/report.html). The letter sent to the Galántais in 2005 is available in Hungarian. Galántai decided to make public several reports concerning his activities during the period in which he was under surveillance by the Hungarian State Security (1979-1988). The original folder is preserved in the Archives of the State Security (ÁBTL), it can be consulted by accredited researchers with Galántai’s authorization.)

JK: True, but you can also see things he didn’t understand at all, things he mixed up. He was combining information, but this had nothing to do with the works themselves. There were only political speculations behind it all.

JD: The report also mentions the names of members of the Hungarian democratic opposition who were present at the opening. Do you think their presence might have influenced the ban on the exhibition, as a place where persons considered “hostile” to the regime could gather and conspire?

JK: People really didn’t know that the exhibition had been banned, they heard it only when they came to the opening. These members of the democratic opposition were very often present at the Young Artists’ Club; this was a place where one could feel a little bit more free and meet other people, although you knew you were being watched. Artists were taking risks in organizing events, and as far as I know, some politicians really used these public initiatives for their own business. At that time, we considered this normal, we thought we could help the opposition by organizing events where they could meet and demonstrate. In my opinion, this was the artists’ contribution to the changes, but very quickly, the politicians forgot about all this. The worst example maybe that of the Inconnu group, which was marginalized.

Looking back at the last twenty years, I think the avant-garde didn’t get from the politicians what it deserved for the service they did them, on the contrary.

Budapest, January 12, 2011.