Post-Diaspora: Notes on the Second World’s Exile, Postmodernism, and Diaspora Nationalism

A question of paramount importance must be raised once again before one can open a discussion on the subject concerning the post-Soviet diasporic condition and the cultural production of the post-Soviet diaspora.

This question is of a rather geographical nature, namely, where is the Second World to be found now in 2003?

Has it dissolved and disappeared into oblivion now that its political and social structures have been discredited or disintegrated and its cultural production proclaimed nonparadigmatic?

A question of paramount importance must be raised once again before one can open a discussion on the subject concerning the post-Soviet diasporic condition and the cultural production of the post-Soviet diaspora.

This question is of a rather geographical nature, namely, where is the Second World to be found now in 2003?

Has it dissolved and disappeared into oblivion now that its political and social structures have been discredited or disintegrated and its cultural production proclaimed nonparadigmatic?

I would like to argue that perhaps it is not in the vast lands of Eastern and Central Europe that one should be looking for the ghostly remnants of the Second World.

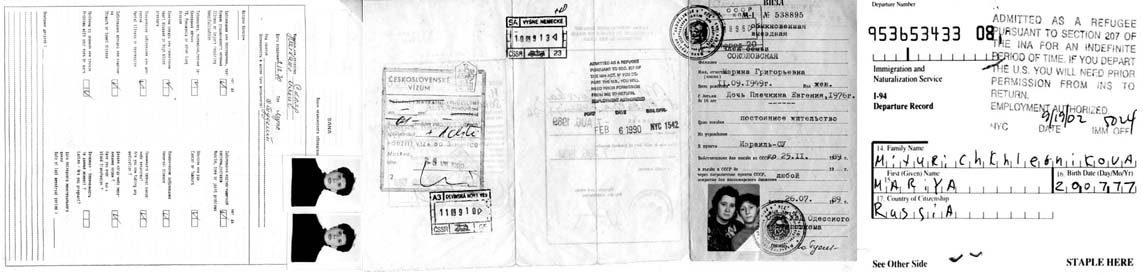

The construction formerly known as the Second World was substantially displaced to the ethnic ghettos of Western metropolises beginning in the late 1980s and ’90s, when an estimated three million former holders of red USSR passports found themselves in “world number one”.

This mainly self-imposed displacement (though sometimes assisted, which in the late 1990s and 2000s became a reincarnation of the Soviet-era persecution of political dissidents) was both a product of the trauma from the first few years of glasnost and perestroika, and a continuation and acceleration of pre-perestroika immigration dynamics.

The exodusof the late 1980s and ’90s was a consequence of a kind of mass hysteria of awesome proportions that occurred in the post-Soviet space.

This hysteria was precipitated by political and economic upheavals during this period and subsequently led post-Soviet subjects to assume the role of “the Other” in Western cities, and, at the same time, was a rather radical upgrade of a pre-perestroika diaspora.

The critical point of this historical shift, in my reading, was during 1994.

During the spring of 1994, Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn made his historic and much-publicized return to Mother Russia after almost twenty years of exile in Vermont.

Solzhenitsyn arrived extravagantly in the easternmost part of Russia, then traveled by train through the vast country towards Moscow, making stops along his way to schmooze with the Russian people (who greeted him enthusiastically on the station platforms).

This arrival marked the beginning of a distinctly new era in Russian diasporic politics.

While Solzhenitsyn was moving westward by train, self-displacing Soviet subjects were boarding planes and flying to the West as though the great writer was pushing them out of the post-Soviet space in a type of virtuoso mainland-to-diaspora conversion.

Thus, upon Solzhenitsyn’s 1994 return, the Second World went into exile, abandoning, in turn, the majority of its loyal subjects to a state of apathy or even internal dissent.

The spectacle of Solzhenitsyn’s homecoming illuminates nothing less than a shift from the essentially postmodernist rhetoric of late-Soviet art to the high modernist rhetoric of the 1990s.

Solzhenitsyn’s choice of a train as his means of transportation for his return signaled the reemergence of the modern, evoking the constructivist propaganda trains of the October Revolution era.

The choice of the train mirrored a melodramatic, petit bourgeois 1990s remake in which the splendor of the great steam diesel engine of the 1920s, that beloved subject of the Russian constructivists, was substituted by the ugliness of the late-Soviet locomotive.

Undoubtedly, the post-Soviet cultural situation in the early 1990s was prepared for a continuation of the postmodern project, for a peculiar brand of moderate postmodernism (of which Sots art was an eloquent example) had developed quite naturally in the Soviet Union during the 1970s and ’80s.

However, the collapse of the Soviet Union in the early 1990s slowed down the much-anticipated advance of postmodernism and high-modernist rhetoric made a sudden and violent return.

Cultural production on the post-Soviet mainland, especially in Moscow, seemed to privilege high-modernist logic, with its glorification of innovation and novelty in the cultural sphere.

In ’90s Moscow, it was commonplace to stress, for instance, the movement quality of Moscow Actionism (whose practitioners included Alexander Brener, Oleg Kulik, and others).

This was during a time of postmodernity when no artistic movement or even periodization, for that matter, was possible, for the aesthetics of the great masters, movements, and linear chronology carried an unambiguous family resemblance to high modernism.

Mainland Russian production was doomed to function along the high-modernist trajectory, as cultural production in Moscow was hijacked by the political and social upheavals of the 1990s.

Cultural motivation was fueled by the necessity and inevitability of progress and innovation in the cultural sphere (and in that mirroring the political and social progress and innovation): an ordeal that the West, and post-diaspora as its internal “Other”, was fortunate to avoid.

The diaspora, on the other hand, progressed along a different trajectory. By the late 1990s it had become apparent that the majority of post-Soviet diasporic artists and intellectuals (with the exception of the so-called professional nomads) neither represented the new Russia nor mediated between the new Russia and the West.

Post-diaspora carries a unique symptom: Its artists and intellectuals appear to represent the seemingly absent Second World.

I argue that the encounter with the post-Soviet diasporic cultural production of the 1990s and 2000s is an encounter with a displaced Second World (late-Soviet) postmodernism, which was, naturally, carried to the West in the late 1980s and 1990s.

Post-Soviet diasporic artists remained within the postmodern paradigm because late-Soviet postmodernism was the very foundation of their cultural identity.

The Russians in diaspora have become a database in which diverse entries manifest the postmodern fragmentation and the rejection of wholeness.

Ironically enough, this “database logic” is the return of the repressed of the departmentalization of the Moscow Union of Artists, in which Ilya Kabakov, for instance, was assigned to the book-graphics department.

In the 1990s and 2000s, the Second World became an empty designation that can easily be filled by peculiar combinations of Western marginal identities.

It seems as if the database logic of post-diaspora historically concludes the project of the identity-politics discourses that were prevalent in the 1990s.

It is perhaps to the historical return of high modernism to Russia after the collapse of the Berlin wall that we can attribute the continuing and seemingly impassable East-West dichotomy, a situation that nobody had expected in hopes that the gap between East and West could be easily bridged.

Simply put, Russia, in its essentially high-modernist agony of the 1990s, was incapable of joining the West in the era of textbook postmodernist practices.

Surprisingly, it seemed to have been more ready during the 1980s, but by the 1990s the historical moment had passed in the midst of social and political restructuring.

The West was not prepared for the sudden collapse of the Eastern bloc; its postmodernist constructions experienced an impact.

They leaned, but recovered and remained standing. The East, in turn, undertook several recovery attempts of its own by taking on several exclusively Western discourses, including, quite unsuccessfully, that of postcolonialism.

It must be noted also that the exile of the Second World’s artists and intellectuals to Cuba or China would have seemed much clearer politically but not culturally.

Culture workers of the Second World sought asylum not in the still-remaining oases of quasi Marxism but in the countries of the First World, effectively substituting their art-historical motivations (perpetuation and advancement of late-Soviet postmodernism) for its political agenda (dissent toward the policies of the new Russia).

The West proved to be a database of such a monumental scale that it was able to absorb the Second World as one of its own internal Others.

The entries in the post-Soviet diasporic database range from artists, to refugees, to professional nomads, to the new breed of political dissidents, to economic opportunists, to hardened criminals, to retired KGB agents, and so on.

In the cultural sphere, a new generation of post-Soviet diasporic artists has come to the art scenes of the West since the late 1990s.

These artists either came to the West as children or teenagers or merely launched their careers there.

In contrast to Russian émigré artists of the 1970s and ’80s (the “high” diaspora), who came to the West as mature and ideologically conditioned individuals, this new generation is unified by its typical postideological pluralism and its active participation in what are commonly thought of as exclusively Western topics of discourse.

This distinction inevitably calls into question the authenticity of their work.

The post-Soviet diasporic subject embodies a complex juxtaposition and overlapping of cultural, ethnic, religious, gender, and sexual identities, which creates a different narrative from that of mainland Russia.

This subject is the “Other” in transition, a postideological work in progress of Western modernity: this diaspora is an extremely flexible and ever-changing organism.

The diasporic artists of the 1990s and 2000s generation are casualties of the postideological condition on the one hand and displacement on the other.

Nevertheless, these artists often speak of the historical void of the Second World as if the location of the Second World’s discourse has moved from the traditional Second World to this diffused one.

Today, the post-Soviet diasporic condition is characterized by the actualization of a diaspora nationalism that in its extreme manifestations can perhaps be compared to that of the Cuban or Puerto Rican diaspora, in its (un)conscious assumption of responsibility for the mainland’s past (absent Second World).

Post-diaspora both reaffirms globalization (nomadic diaspora) and undermines it (diaspora in local context).

It is precisely because of the tension between the notions of globalism and diaspora in the 1990s that diaspora redeems itself, frees itself from its trauma, and becomes paradigmatic once again. The “high diaspora” of the past has been replaced by post-diaspora.

Diaspora has become a constant reminder of the Soviet past, of the Soviet trauma that the new Russia, in its desperate wish to remain in denial, wants to suppress.

On the one hand, it seems appropriate for post-Soviet diasporic intellectuals who have taken residence in Western metropolises to play along with the Western discourse of the “Other” and, perhaps, to finally find its much-desired niche in the Western (local) cultural landscape through negotiations with other ethnic and marginal groups here.

However, the problem that arises is that the post-Soviet subject is not prepared to assume the role of the “Other”.

The Second World has never thought of itself as the “Other” and keeps mistaking itself for “another” First World.

And this perhaps is the major source of the continuing frustration and misperceptions between the East and West, between the post-diaspora and mainland Russia, and between the post-diaspora and the West.

This article was published previously in “pH: Pro-Contemporary Art Edition” no.3 (Spring 2004) Kaliningrad, Russia.