The Films of Polish Women Artists in the 1970s and 1980s – From the Archive of Polish Experimental Film

The program was staged at the Kitchen (NYC, April 28), co-joining with the exhibition “Architectures of Gender: Contemporary Women’s Art in Poland” (Sculpture Centre, NYC, April-June 2003). Many of the films in the presentation were being shown for the first time since they premiered 20-30 years ago. The majority had been in need of restoration or even partial reconstruction.

When observing Polish art over the last decade, one can discern a somewhat sudden increase in the number of women artists using video techniques.

The presentation of “Films of Polish Women Artists in the 1970s and 1980s” is an attempt to establish the genealogy of this phenomenon; an attempt to explain how, during that time, Polish women artists confronted their ideas and artistic strategies against film and video.

It aims to provide a comprehensive view of independent films (in 8 mm, 16 mm and 35 mm) from that period by twelve women artists: Zofia Kulik, Ewa Partum, Natalia LL, Anna Kutera, Katarzyna Hierowska, Jadwiga Singer, Jolanta Marcolla, Teresa Tyszkiewicz, Ewa Zarzycka, Barbara Konopka, Irena Nawrot, and Iwona Lemke-Konart.

Zofia Kulik – Open Form , 1971, scene: Game on the face of the actress (realization: Zofia Kulik, Przemyslaw Kwiek, Jan. S. Wojciechowski)

|  |  |

In 1971 Zofia Kulik took part in the realisation of the film titled Open Form , which was carried out jointly by the students of Lodz Film School and the Department of Sculpture of the Warsaw Academy of Fine Arts (where the artist studied).

This intermedial work attempted to activate in different ways the relationships between film and other visual arts such as sculpture, painting, happening, public interventions, performance(The Open Form film, alongside other films produced later by Zofia Kulik and her partner Przemyslaw Kwiek in co-operation with film makers, such as Dzialania (1972) and Dzialania na jednominutowkach innych (1973) form together a very interesting variation of Polish intermedial cinema.) .

In their practice the co-authors of the film advocated a change from existing “fetish-like,” hierarchical relations between the recipient and the creator towards more “democratic” models of artistic communication.

Being more interested in initialising and analysing the process of artistic realisations than in producing traditional, “objective” works of art, they promoted participatory aesthetics, and an inter-medial attitude of transgressing inter-artistic borders (also those separating art from life).

The team put emphasis on the co-operation of artists from different specialisations learning how to integrate their skills to work together. There was also more stress on communication and cognition than on presentation.

All of the above-mentioned properties created a context for developing the formula of group visual games, which allowed the games to take on a process structure of subsequent moves – made by “players” in a specific sequence.(Ronduda, Lukasz. Dzialania na jednominutówkach innych KwieKulik (www.csw.art.pl/foundfootage).)

The scene entitled “The game on the Face of the Actress” is a good example of a visual game, where each subsequent shot represented another move by particular artists.

The players (who are not visible in the frame) are gathered around the face of an actress. Their moves (called steps by the artists) require each player to integrate three important aspects.

First, to react to already existing facts (former moves of the players); second, to unfold one’s own expression; and third, to remember that by moving, one creates the context for the move of the subsequent player.

The artists communicated (played) using both visual forms, and various sorts of activities.

The name of the actress is Ewa Lemalska. She was quite famous through Janosik, a very popular TV series in 70s Poland.

She played Maryna – Janosik’s girlfriend and was a kind of celebrity of that time. This TV series was broadcasted parallel to the projections of the Open Form film with the scene “The Game on the Face of the Actress.”

And it turned out that this realisation acquired a strong critical dimension towards the pop culture context of 70s Poland.

Zofia Kulik – Open Form , 1971, scene: The revealing of complex form (realization: Zofia Kulik, Przemyslaw Kwiek, Jan. S.Wojciechowski)

|  |  | |

|  |

Another technique invented during the making of Open Form was “The revealing of complex form”.

The artists wrote: “The results of the artists’ work should be fit for use by the recipients as information illuminating (explaining) current problems and relations of reality”.

The artists’ desire was to knock the recipients out of the “rhythms” or “strings” of social life, of dominant models of perception, as well as an attempt to put the recipients in a situation where they were forced to ask themselves questions about the social, functional, cultural (and – connected with all previous ones – formal (of material and space) mechanisms in which they were stuck.

Through “revealing the complex form” the artists strove to create certain cognitive situations, trying to define the character of the reality in which they lived and worked.

They did so by putting an unexpected (“abnormal”) element into the context of public life, as in the scene “The revealing of complex form.” In the scene the actress – Ewa Lemanska – is behaving very provocatively in the context of a public space in Warsaw at the beginning of the 1970s. It is worth mentioning here that the turn of 1970/1971 – when Open Form was filmed – was a very disquieting time in Poland. It was a period of numerous changes within the socio-political sphere, and of a change of government.

Zofia Kulik – “Synchronisation of An Open Form film projection onto three screens”, 1971 – reconstr. 2001, (realization: Zofia Kulik, Przemyslaw Kwiek)

Zofia Kulik went about her diploma work in 1970 and 1971. The work adhered to the process method and consisted of two parts: one was to make a copy of the Michelangelo Buonarotti’s sculpture Moses by using hardened coloured rags, the other to prepare a simultaneous projection of about 500 slides onto three screens surrounding the viewer.

The slides shown during the three simultaneous projections constituted a kind of Kulik’s visual notepad. Since the beginning of her studies, the artist registered important events in her life, both artistic, and more personal.

This slide show was aimed at sorting out the visual material and connecting formal elements from different situations into micro-stories.

When recording a given part of the visual material (things, people, matter, etc.), the artist would often modify and animate it. Slides that documented these modifications were later put together to form a complex narration on the screen.

In 1971, concurrently working on her diploma, the artist was involved in a group realisation of the film Open Form .

After the film had been completed, the artists (Zofia Kulik i Przemyslaw Kwiek) tried several times to combine the screening of Open Form film with the two (or three) slide projections. It is worth noting that this work follows the idea of Kulik’s diploma.

Artists knew that when the show is projected on three screens, the viewer’s sightwould be released; the viewer is given the possibility of changing his or her point of view (unlike in the case of a traditional cinematic projection) and as a consequence – the viewer could take some control over the creation of the work.

In this instance we can say that “the reception structure is freed from the permanent supervision of the work”.

The viewer’s gaze is being freed and the viewer is required to become an active participant between the three simultaneous projections.

A similar situation occurs during the show when the artist introduces the so-called Interrupted Projection—a sudden interruption of the show, lights turned on, and artists trying to provoke interaction with the audience.

The process of film reception had to be different from peaceful contemplation, so characteristic of classic film shows. Its ideal (in the artists’ assumptions) was active participation of the audience in the activities initiated within the framework of the show.

In 2001 Zofia Kulik managed to reconstruct one of the said combined shows of the film Open Form and slides for three screens (“Synchronisation of An Open Form film projection onto three screens”), using scores from the seventies. These scores meticulously determined the projection narration scheme.

This realisation is an interesting document of expanded cinema, and also shows very well how the recent work of Zofia Kulik, as an “organiser of very complex epic visual structures,” is a specific continuation of what she had been doing (at the beginning of the 1970s.

In “Synchronisation,” one of the artist’s first realisations made by both Kulik and Kwiek we may note a number of characteristic elements, determining the shape of her future work (such as photo-carpets). For example, “Synchronisation” expresses an original construction and similar organisational regime of complex visual structures (the manner of relating both individual narration and singular elements in relation to themselves and to the whole of the composition etc.).

Let us emphasise here that Kulik makes her current works in part out of materials registered during the seventies.

In the light of the above information, we see that this show from the early seventies is linked with the artist’s contemporary work by, for example, the occurrence of “visual idioms of the soc-age” (images of totalitarian architecture, draperies, monuments and statutes, the Palace of Science and Culture, May Day marches etc.).(Piotrowski, Piotr. ed.. Od syberii do cyberii (Poznan 1999).)

Ewa Partum – Tautological cinema : Poem by Ewa (1973)

The cycle of films entitled ‘ Tautological cinema ” is a thorough presentation of the creative work of Ewa Partum during the 1970s.

The majority of pieces belonging to this cycle are related to actions and activities connected with visual poetry.

Visual poetry has been the main area of the artist’s creative interests since 1969, along with films contained in the structural cinema paradigm.(Ronduda, Lukasz. Kino Tautologiczne Ewy Partum, Exit nr 3 / 2003.)

“Poem by Ewa” is a film documentation of ephemeral and volatile activities centred on visual poetry: the scattering of single letters of the alphabet, thrown into the wind, into the sea.

These activities were a continuum of such pieces as Thearea on poetic licence (1971) or Active Poetry (1971).(Ewa Partum 1965 – 2001, (Berlin 2001).)

This gesture was aimed at deconstructing traditional, and in her opinion, “used-up,” canons and forms of poetic expression.

The act was motivated by the need to replace conventional grammar and linear syntax of language with more open, process structures, thereby incorporating into the process of their formulation, the actuality of chance, and the creative activity of the recipient.

The deconstruction of syntactical and grammatical structures of language and the creation of anarchist and “drifting in the world” poems may be seen through the context of later feminist activities of the artist as an act of contesting language – i.e. the “medium of patriarchal world values.”

Ewa Partum – Tautological cinema : Film by Ewa (1973)

|  |

Film by Ewa (1973), the first film from the Tautological cinema cycle, does not bear any resemblance to a document.

It is an autonomous cinematic realisation conveying the impossibility of communicating one’s own ideas.

Covering her mouth, eyes, and ears, to signify that the idea is within the artist and thus unable to be conveyed, Partum formulated a concept, which – as it was her objective – describes the alienation of a conceptual art creator.

The artist-creator cannot express his/her idea, which, when materialised on a medium or entering into the field of experience of another person, becomes distorted and distant from the original.

Ewa Partum – Tautological cinema : 10 meters of tape (1973)

Apart from the realisations connected with visual poetry, the Tautological cinema cycle characterizes a collection of films contained in the structural cinema paradigm.

For example, in 10 meters of tape Partum takes up the problem analysing the film medial properties.

The words: “1 metre, 2 metres” etc. have been placed into the structure of the film and present the actual flow of physical metres of film tape through the projector.

Ewa Partum – Tautological cinema : Drawing of TV (1976)

Drawing of TV is one of the last (1976) films from the Tautological cinema cycle. This realisation constitutes a specific intervention into the sphere of public media and further advances (in addition to moving into a different dimension) the former actions of Partum.

An example of this active progression and intervention is seen through The Legality of Space (1971), which was carried out in the public reality of Poland during the 1970s and was often critical in its intent.

Drawing of TV, was conceived by the artist drawing with a felt-tip pen on the screen of a switched-on TV. She was creatingspontaneous commentaries to the broadcasted programme.

The fact that the artist “intervened” only with news and information programmes such as “Wieczór z dziennikiem” or “Dziennik telewizyjny” – through which there were a number of propaganda slogans and images – allows us to interpret her expression as a critique of the over-ideologized public media in seventies Poland.

The act is also a protest against television as a mass medium, that is an instrument of the executive power.

The construction framework of Drawing of TV is defined by “re-filming” – one of the basic methods of structural cinema.

This realisation is characterised by a specific aesthetics of the trembling, flickering image, built on the frame speed difference between the 8mm camera registering the TV screen and the TV monitor image refresh rate.

This effect corresponds well with the strategies of structural cinema artists who included all kinds of noise, dirt, etc in their films, in order to bring out the medial properties of the film.

To that end the flickering picture of Drawing of TV may be interpreted as a visualisation of the difference between mechanical and electronic media – as a specific trans-media communication.

At the same time, we may treat Drawing of TV as yet another symptom of “the artist’s opening onto history,” which was taking place during that time.

It was her transition from “contemplating general issues present in conceptual art” toward “reflecting on socio-political problems.”

It was at this juncture that Partum started to formulate the feminine problems in her pieces in a more radical way.

Ewa Partum – Performance documentation – “Change. My problem is a problem of a woman”, Art Forum Gallery, Lodz, 1979. Action documentation – “Self-identification ”, Mala Galeria, Warszawa, 1980.

|  |

Since the late seventies the artist has gradually moved from the issues of autonomous conceptual art and contemplation of purely artistic problems to taking up feminist issues in her creative work.

This transition has been marked by the use of the artist’s naked body in her performance art.

Partum appears naked to stress a specific “location” and “subjectivity” of her creative expression – the need to stress that she is, above all, a woman who speaks.

In 1979, Partum performed Change – My problem is a problem of a woman (Galeria Art Forum, 1979).

During the performance, she, with the help of make-up artists, carries out the act of ageing on the right side of her body, thus subversively alluding to the compulsion of making the body look younger and more beautiful: a compulsion to which women commonly fall victim.

This action was accompanied by broadcasted statements by Valie Export, Urlika Rosenbach and Ewa Partum herself through loudspeakers: “Woman can only function in these alien societal structures if they master the art of camouflaging themselves and deny their own personality.”

In 1980, Partum performed Self-identification . During this action, Partum enters into the public space naked.

She carries out in reality a vision made out of her photomontage (presented at that juncture in Galeria Mala) showing a naked woman (Partum) in various contexts of the Polish public sphere of the late seventies, e.g. in front of the presidential palace, in a shop.

This action can also be interpreted as a provocation against the institution of marriage, since the naked artist confronts herself with a newly-wed couple and a crowd of wedding quests.

Natalia LL – Consumptive Art (1973)

|  |

Natalia LL started her film and photography experiments as the first of the artists presented here.(Sztuka i Energia (Muzeum Narodowe, Wroclaw 1994).)

She worked in Wroclaw, a city which by the turn of the sixties and seventies had become the centre of Polish conceptual art.

LL started criticising restrictions of the analytical version of conceptualism relatively early, seeing it as overly rationalised.

Her work during this period is characterised by the juxtaposition of powerfully “hot” erotic motives (deliberately opposing discourse or rational system analysis) with “cold” instruments of conceptual art.

Such a stance is borne out of her realisations related to permanent photography strategy, “intimate photography” installation, and ultimately “ Consumptive Art ” or “artificial photography”.

“ Consumptive Art ” is one of the artist’s best-known pieces. It is on one side an attempt to compromise the cognitive ambition of conceptual art, and on the other an effort to critically relate to the iconographic sphere of popular culture that frequently employs erotic motives.

This aspect of the artist’s work has often been the subject of discussion. For example, Piotr Piotrowski,(Piotrowski, Piotr. Dekada, (Poznan 1991).) who denied the work any demystifying or critical dimension towards the mass culture during the seventies and provided the social context from which these works sprang.

He pointed out that the reality of 1970s Poland was that of a puritan socialism, devoid of mass culture saturated with eroticism.

As such, erotic motives were very rare, and even when they came out into the open, the projected model of the woman was asexual.

According to Piotrowski, this piece of work becomes a-critical of consumption – rather encouraging it than analysing it, yielding to it rather than describing it.

From the standpoint of feminist critique, the work of LL has been interpreted many times as deconstructing visual perception models (the canons so characteristic to Western culture which institute the role of a woman as an object of visual consumption by a male viewer).

It has often been stressed that the Model in the “ Consumptive Art ” frees herself from the role of “object of erotic contemplation,” is autonomous and, similarly to LL’s other works, becomes a figure of a woman exploring the realms of her own sexuality. From a passive object of desire she becomes a fully empowered subject.(Kowalczyk, Izabela. Cialo i Wladza, (Poznan 2003).)

Katarzyna Hierowska – Murderer (1975) (filmed with Stanislaw Antosz, with the nom de plume of Antosz & Andzia).

Apart from structural and intermedial cinema, another strong strand in Polish experimental cinema was pop-art.

It must be stressed that in the seventies there was a strong current of artists who regarded their work as an attempt to critically or to affirmatively relate to the sphere of popular culture.

Apart from Natalia LL, this group included Zdzislaw Sosnowski, Janusz Haka, Jacek Drabik and Antosz & Andzia.

The work of Antosz & Andzia is characterised by its multi-element play on the reality of TV serials and Hollywood movies.

Conversely, their films or cycles of photographs pretend to adhere to (mimic) the stylistics of the dominant tendencies of Polish art in the seventies (focusing on cognitive objectives, examining reality or creating models to explain it, etc.) with the sole aim of ridiculing them.(Antosz & Andzia. Dwie uwagi dotyczace koncepcji filmu w Photelart’ie, Stare Zajecie (Galeria Labirynt, Lublin 1977); Antosz & Andzia, Pholetart (Wroclaw 1976).)

Antosz & Andzia pretend to be scientific by using modular structure in their films, where subsequent parts show variations of the same situation (variations on the same theme).

Their theoretical manifestos and programmatic texts have an ironic and absurd side to them.

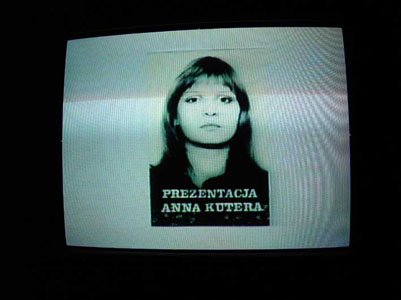

Anna Kutera – Presentation (1974)

|

Anna Kutera was closely linked with the artistic community of Wroclaw, where she co-created The Recent Art Gallery with Romuald Kutera and Lech Mrozek.

In the mid-seventies these artists were augmenting the contextual art theses of Jan Lwidziski.

The Lwidziski model of contextual art held that the dominant conceptual art model should be abandoned for a more pragmatic one – one with more focus on the concrete context (i.e. social, political, economic etc.) in which art operates.

“Contextualism” was opposed to the separation of art and reality into distinctive independent spheres.

The contextual artist, assuming the attitude of an engaged anthropologist, does not contemplate (speculate) but rather inwardly participates in the reality “under investigation.”(Piotrowski, Kazimierz. Sztuka jako sztuka kontextualna, Exit 1995; Lwidzinski Jan, Art as Contextual Art (Sellem Galerie 1976); Lwidzinski, Jan, Quotations on Contextual Art (Eindhoven 1988).)

Lwidziski and Kutera maintained close tieswith other artists – either individual exponents of the post-conceptual movement such as Joseph Kosuth from the Anthropologized Art Period, or groups such as Collective Art Sociologique and Sistema Latino America.(Por: Piotrowski, Kazimierz. op. cit.; Sztuka Kontextualna w Galerii Najnowszej, 1977 (Galeria Sztuki Najnowszej, Wroclaw 1977).)

The Presentation by Anna Kutera offers a number of very slight contextual interventions (almost completely integrated into the sphere of social interactions).

Jolanta Marcolla – The Kiss (1975)

|

At the beginning of the 1970s Jolanta Marcolla was one of the founding members of the group of artists known as “The Actual Art’s Agency”.

The members were students and graduates from the Academy of Fine Arts in Wroclaw (painting and sculpture departments) with a particular interest in film and photography.

In her films, Marcolla focuses on the analysis of media properties of film and video (concentraiting mainly on the analysis of the relation between film and the reality depicted within it).(Stokzosa, Bozenna. Obiekty i ich widoki, Jolanta Marcolla (Galeria Labirynt, Lublin 1978).) She presents her movies as very long film loops.

It has to be emphasized that Marcolla was the first Polish female artist to select video.

Her first piece – closed-circuit installations – was completed in 1975. These projects were performed in Lodz with the help of the members of “Warsztat Formy Filmowej” (Film Form Workshop) – the most important faction in Polish structural cinema and analytical video.

There was a direct affinity between Marcolla and the Workshop’s artistic pursuit, as both focused on the analysis of contemporary artistic media.

Jadwiga Singer – The End The End (1979)

Jadwiga Singer was a founding member of Laboratorium Technik Prezentacyjnych (The Laboratory of Presentative Techniques).

This entity came into being in 1975 at the Academy of Fine Arts in Katowice, as a Special Interest Group in the department of graphic art.

The principal aim of the group was to promote work that defied the established curriculum of art courses.

Under the adopted name of the group, its members started analysing various media such as film and TV.

They endeavoured to develop their own variety of structural cinema and analytical video.(Laboratorium Technik Prezentacyjnych, Inne Media (Galeria Studio, Warszawa 1978).)

Jadwiga Singer’s film “Koniec Koniec” (The End The End ) shows an interest in media issues, the film-making process as a subject, or relations of materials which determine cinematography as a medium.

The artist is also interested in using structural cinematic instruments to formally organise images.

One can observe that Singer’s film achieves a particular balance between the artistic and meta-artistic discourse.

The motif of closed composition (on which “The End The End ” is based), is of a circular nature, in which the end signifies the return to the point of departure and is frequently employed by the artist.

Teresa Tyszkiewicz – Grain 1980

|  |

Teresa Tyszkiewicz began her artistic pursuit in 1978. Between 1978 and 1981 she was connected with a hub of artists centred on the Warsaw Contemporary Gallery (Galeria Wspólczesna).(Tyszkiewicz, Teresa. Film poza kinem, (Galeria Jatki PSP, Wroclaw 1981); Bojko, Szymon, Film poza kinem (Kino nr 5 / 1981).)

She made her first 16mm film with her husband, Zdzislaw Sosnowski. Alongside performance art, film quickly became one of the main media of her creative expression.

Films by Tyszkiewicz are very characteristic of the changes that were taking place in Polish art at the end of the seventies.

The focal point of these changes was the transition from analytic, structural, and systematic interests (from objectivism and rationalism) to strongly expressive tendencies, using powerful emotional, radically subjective, and intuitive means – the qualities characterising the art of the following decade.

Tyszkiewicz has often stressed that her films were unscripted – i.e. originating from spontaneous (unconscious) impulses.

They were aimed at visualisations of subjective emotions and non-verbalized desires, whose expression required the artist to seek her own original aesthetics or form of expression.

In this way she justified the need for experimentation.(Jankowska, Malgorzata. Obrazy wyobrazni w ruchu, Film artystów (Torun 2002).) Assigning more value to sensuality and spontaneity, at the expense of rational control over the work of art, causes subsequent films by Tyszkiewicz to resemble a set of “tests” of emotional reactions, attempts to express the artist’s intuition.

This explains their specific rules of construction. They are usually composed of several modules, depicting subsequent actions carried out by the artist, but one does not logically imply or cause the other.

The most clear-cut rules of construction at the base of each scene are designed to confront the artist’s naked body with various materials (glue, cotton wool, grain, pins, etc.), as well as to depict the body through various mechanical (often monotonous and absurd) activities.

Through the experience of the body, through experiencing its mechanics, its physical side, the identity of its substance with other surrounding objects (materials or machines), Tyszkiewisz – as she herself states– deliberately erases the precise border between the self and the external world.

Tyszkiewisz deliberately reduces herself to an “animated fragment of matter.” Partly because of the above mentioned characteristics, Tyszkiewicz’s films have been interpreted as an example of écriture feminine in the field of film.

Ewa Zarzycka – Symptoms (1980)

|

Zarzycka’s Symptoms was critical of medialism – an artistic approach dominant in the seventies and, according to the artist, one representing a barren reflection of the nature of the used media.

The whole film is full of humorous and absurd references to medialism, from the dialogue and props to the dominant aura of a masquerade, a paratheatrical atmosphere was supposed to express a reaction to “de-subjected”, a-literary media analyses.

Symptoms belonged to the rather popular kind of artistic activities created outside the scope of official artist institutions, mainly in art galleries set up in people’s apartments at the beginning of the 1980s.

Such activities gained popularity especially after martial law was introduced in Poland (1981), and constituted the independent culture of this period.

The film was made as a silent movie. There was dialogue written for it, which was initially to be inserted into the film on dialogue boards. However, the artist finally decided to read it aloud during the shows.

I would like to quote a fragment of the dialogue list that the artist herself read during the show:

“There are two characters in the film:

Ms X – a woman of a certain age – between 130–140; still beautiful; dressed in a white or black gown.

Mr Y – a man of between 350 and 380 years of age; nonetheless exceptionally elegant and charming; wearing a dark suit.

Ms X and Mr Y have spoken to each other a lot of words in just any language. In all sorts of situations. Not all the words require translation, not all of them are translatable. The situations may or may not be understood. Some of the words are contained in dialogues. Here are some of those:

For example, Mr Y asks Ms X:

– Don’t you think, Madam, that photography is a razor in the paws of a monkey?

And Ms X answers:

– Oh, no. I have consciously chosen this medium and I am still examining its properties.

Mr Y is silent.

Now Ms X asks:

Don’t you think, Sir, that the symptoms of spring that are existing around us, are capable of changing our visual identity?

Mr Y:

– Please take into account that no certainty has in itself the characteristics of a factual certainty.

Ms X:

That film is an appropriate medium?

Mr Y:

Accidentally, Madam, don’t you think that the end of photography and film seems to be imminent?

Ms X:

Oh, yes, chance allows for a great range in character and intensity of contact, from an elusive reflection to a powerful life-threatening shock.”(Zarzycka, Ewa. Symptoms – dialog list, 1980 (Centre of Documentation and Research, CCA).)

Barbara Konopka – Interferences (1985)

“ Interferences ” – a film by Barbara Konopka – depicts a number of self-manipulative interventions of the artist on her own body.

In the accompanying text of the work, the artist states: “This form of self-manipulation manifested one’s own autonomy towards external, social manipulation practices.”(Konopka Barbara. Interferencje 1985 – 2000 (Centre of Documentation and Research CCA).)

At the forefront of Konopka’s mind was the socio-political reality of Poland after the period of martial law, still replete with police brutality and military dictatorship propaganda.

Directly after the making of Interferences , Barbara Konopka, together with Zbigniew Libera and Jerzy Truszkowski, established the Sternenhoch group, whose activities included painting pictures, playing concerts, organising happenings, as well as other forms of actionism.(Truszkowski, Jerzy. Od nihilistycznego aliansu orgiastycznego do infekcji memetycznych, Kontperformance 7 (Galeria Kont, Lublin 2003).)

The performances, in addition to video realisations carried out by the group members, have drastically emphasized issues of the body.

Worth mentioning is Intimate Rituals by Libera, or Truszkowski’s realisations where the artist carves out symbols of political or religious authority on his body with a scalpel.

Another important layer of the film’s meaning is the aspect of reflection on the nature of the selected media.

Konopka’s film is a specific trans-medial story about the differences between mechanical and electronic media.

When the artist transcribed Interferences onto a digital medium in 2000, she decided to leave the sound of a running film projector on the sound track; she also tried to highlight the materiality (the specific characteristics of the material) of the celluloid film.

After its transposition onto an electronic medium, the film (super 8 mm) gains, according to the artist, yet another dimension. This is the reason why the film has been supplemented with a pulsating effect (quasi strobe), which stresses the phenomenon of emission: medial conditions of screen image reception.

The effect of this “pulsating white light” adheres the viewer to the fact that that the TV screen is a lamp emitting its broadcast into the viewers body (as opposed to a cinematic projection). This effect allows the artist to accentuate, for example when watching (or being watched through) TV, that the viewer’s body – as the TV projection screen – is being constantly bombarded with a large number of extra-conscious stimuli.

This type of medial conditioning of TV is often used by advertisers who, through image flickering or pulsation effects, affect our bodies (making us follow the events on the screen – commercials) rather than our conscious decisions.

Revealing a source of potential manipulation, the artist writes: “Strobe effects used in the film act subliminally on the viewer’s body, the viewer becomes the object of manipulation parallel to the author’s body which the viewer is observing.

The manipulation of the body takes place in the presentation layer, as well as in the sphere of the viewer’s contact with this work (in the sphere of “dispositiv”). The character of this work determines that it can only be presented from a monitor, i.e. not using a projector.”(Konopka, Barbara. op. cit.)

These two aspects, the issues of the body and the reflection on the nature of the selected media, have always been present in the artist’s work.

Currently, in hercycles of digital photographic images, Konopka picks up on the problem of body identity and perception changes in the context of cyberspace.

The aggression against one’s own body (one’s own sexual attributes), included in Interferences finds its particular culmination when the figure of the Binary Man is introduced (a cycle of digital photographic images Illuminations On-line Binary Man) – “an extra-sexual being” (ultimately divested of sexual attributes).(Jakubowska, Agata. Cialo zenskie – meskie – nijakie (Katedra, nr 1, Warszawa 2001, str. 85 – 90); Ronduda, Lukasz Ci, którzy uniemozliwiaj rozwiniecie sie jednosci sa twórcami anionów (Galeria FF, Lódz, 2000).)

Irena Nawrot – The Yellow Film (1985)

Irena Nawrot has for many years been active in the field of photography. The films she made in the eighties complemented her photography cycles.

The rare screenings of these films always took place in the context of the artist’s exhibition openings, and formed part of a more complex artistic presentation, consisting not only of films, but also photography cycles, poetry, performance and music.

Her first film The Yellow Film was made in 1985, and premiered the same year at Nawrot’s individual exhibition opening at BWA, Lublin.

On several occasions during the show the artist went into the light of the projector to face the audience. She was wearing the same dress as in the film – a yellow piece with black dots.

She was uttering short poetic texts. The exhibition only displayed photographic self-portraits of the artist (in “1 to 1” scale – that is 160 cm high) wearing the same dress both in the film and in reality. These photographs were also shown in the film.

The performances and exhibitions represented an attempt by the artist to touch on some media issues, for example, the identification of reality with a cinematic or photographic representation.(Lechowicz, Lech. Soma i psyche w fotografiach Ireny Nawrot, Irena Nawrot (Galeria FF, Lódz 1995).)

This issue – of the twin relation between reality and its image – has a parallel personal context—an analysis of the artist’s relationship with her identical twin sister (Anna Nawrot).

In some scenes of the film we see Irena, in others Anna, and it is impossible to distinguish one from the other.

The artist refers to all her cycles of photography and their accompanying films as “a visual diary.” She often stresses the links with particular periods in her life and personal development.(Gryka, Jan. Ujarzmiony Personalizm, Irena Nawrot (Galeria Pusta, Katowice 1995); Grygiel, Marek, Dotyk, Dotyk (Galeria Mala, Warszawa 1996).)

Iwona Lemke Konart – The Limits of Human Possibilities (1984)

The majority of Iwona Konart’s film experiments originate from her work in the field of artistic books, which is her main area of creative activity.

The film titled The Limits of Human Possibilities is a cinematic version of an earlier piece executed by drawing and photography.

Just as in her other work, Konart initiates a string of complex inter-medial relations between drawing, performance art, photography and film.

She creates an “autonomous closed structure, within which a particular problem or artistic theme is being solved.”(Rypson, Piotr. Ksiazki i strony (Centrum Sztuki Wspólczesnej, Warszawa 1992).)

The artist elaborates the narration set out in the title by contrasting the shape of the human body with the contour of a mountain range.

To sum up, the most popular trend among the film realizations of the Polish women artists of the early 70s was the structural cinema.

The representatives of it were: Ewa Partum, Jolanta Marcolla, Natalia LL i Jadwiga Singer.

The second important area of exploration of this period were inter-medial realizations, for example Open Form by Zofia Kulik.

From about the middle of the 70s the development of the post-conceptual tendencies can be observed.

The socio –political aspects were included into the artistic works. In this group the works connected with the feminist ideology should be distinguished – the pieces of Ewa Partum i Natalia LL.

In this context we should also mention the pop works in which artists confront the mass culture sphere (for example: Murderer by Katarzyna Hierowska and Consumptive Art . by Natalia LL) as well as realizations connected with profound interference into public sphere of the socialist Poland of the 70s (Anna Kutera).

Among the realizations of the 80s two groups can be distinguished. The first are the realizations that may be treated as a particular reaction on the art of the 70s – as its critique but also its continuation. In this context we should enumerate works of Ewa Zarzycka, Iwona Lemke-Konart, Irena Nawrot.

The second group are the works which demonstratively break with analytical, rational art of the 70s, for example, the realizations of Teresa Tyszkiewicz and Barbara Konopka, which use expressive, emotional, and intuitive elements. They also radically undertake the body aspect.