The Law of the Underground: The Critique of Gender, Performance Art, and the Second Public Sphere in the Late GDR

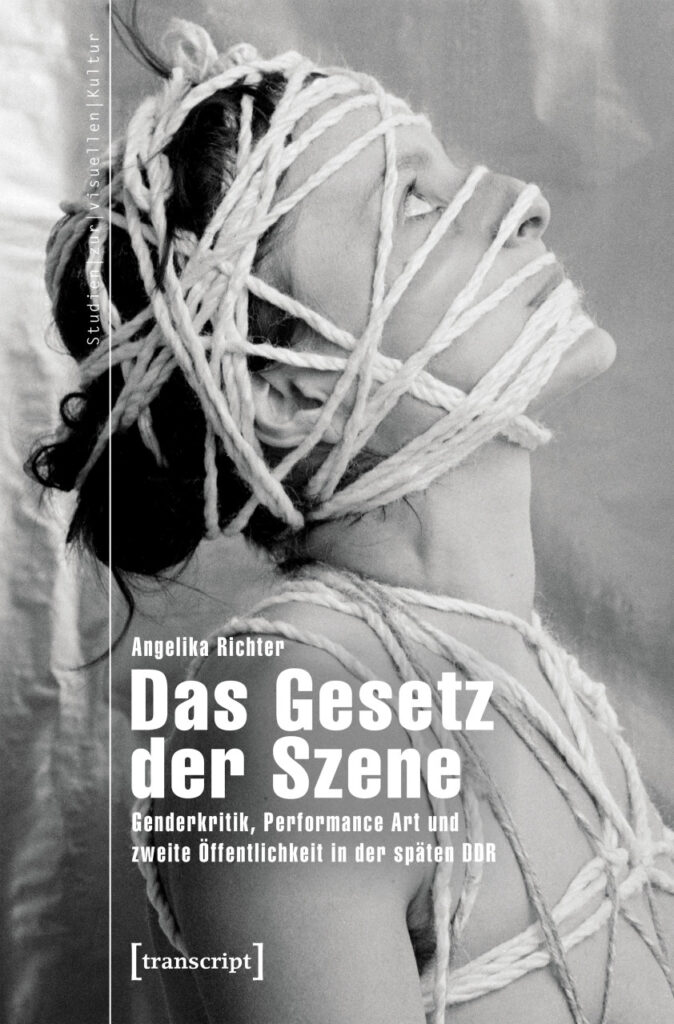

Angelika Richter, Das Gesetz der Szene. Genderkritik, Performance Art und zweite Öffentlichkeit in der späten DDR [The Law of the Underground: The Critique of Gender, Performance Art, and the Second Public Sphere in the Late GDR] (Bielefeld: Transcript-Verlag, 2019), 408 pp.

In 2019, German art historian and curator Angelika Richter published her doctoral thesis The Law of the Underground: The Critique of Gender, Performance Art, and the Second Public Sphere in the Late GDR, in the German language. This book is worth reviewing even three years after its initial publication due to its meticulous research and profound documentation of the self-dramatization and self-empowerment of East German female artists—especially in the genre of performance art—who worked in what the author calls the “second public sphere,” which she defines as the subcultural public sphere that eluded the standardizations of the “first public sphere.” The Law of the Underground comprises three major chapters: “Socialism and the Question of Gender”, “Art and Gender,” and “Showing Gender Differently.” Each of these chapters evolves around Richter’s central thesis that performances by female artists critically negotiated representations of gender, sexuality, and femininity. These performances sought to demonstrate that there is no universal patriarchy, only a plurality of feminisms. Richter contextualizes these female artistic practices in the first and second public spheres of the GDR, and analyzes their sociopolitical and gender-specific conditions of production.

In the first part of the book, Richter meticulously reconstructs the state programs of emancipation that led to significant legal and structural improvements for women in the period under consideration. Already in 1949, the GDR’s constitution guaranteed legal equality for women, and therefore women’s rights became a basic principle for the socialist state. The right to work, granted by the state, enabled women to be active members of society in ways that were previously impossible. Richter also documents qualification and training programs for women, as well as other significant measures implemented to support mothers in the GDR (including free childcare in pre-school and kindergarten and special school programs). The GDR had the highest rate of full employment for women in the world, but women also had to endure the “double burden” of household duties and child care and education, which were still left predominantly in the hands of women. Although women in the GDR had equal legal status to men and were financially independent and secure through their professional activities, traditional gendered distributions of labor still prevailed in the country. Society was dominated by men, as they continued to occupy the majority of leadership positions and women quickly hit a glass ceiling when it came to career advancement.

In the first part of the book, Richter meticulously reconstructs the state programs of emancipation that led to significant legal and structural improvements for women in the period under consideration. Already in 1949, the GDR’s constitution guaranteed legal equality for women, and therefore women’s rights became a basic principle for the socialist state. The right to work, granted by the state, enabled women to be active members of society in ways that were previously impossible. Richter also documents qualification and training programs for women, as well as other significant measures implemented to support mothers in the GDR (including free childcare in pre-school and kindergarten and special school programs). The GDR had the highest rate of full employment for women in the world, but women also had to endure the “double burden” of household duties and child care and education, which were still left predominantly in the hands of women. Although women in the GDR had equal legal status to men and were financially independent and secure through their professional activities, traditional gendered distributions of labor still prevailed in the country. Society was dominated by men, as they continued to occupy the majority of leadership positions and women quickly hit a glass ceiling when it came to career advancement.

In her first chapter, Richter also surveys all exhibitions in the GDR that were exclusively dedicated to women artists, and contextualizes these within a historical framework of similar exhibition projects in other countries. In order to analyze artistic positions that critically address gender roles and attributions, the author elaborates on the characteristics of the alternative “second public sphere” in the GDR, and shows how even this underground was not free from (gender-based) hierarchy. Thus Richter argues that the widespread myth of the “bohemian” underground and the corollary widespread gender differences and gender-specific division of labor within subcultural circles allowed for the emergence of a “patriarchy in private.” For all these circles’ professed egalitarianism, women artists were in fact significantly underrepresented as actors and decision-makers within underground groups and galleries.

In her summary of the book’s second major section, about the representation of gender in the GDR, Richter concludes that even though gender differences and the negative effects of state driven politics on women weren’t addressed publicly, Western feminism was considered a “bourgeois” way of thinking. In the GDR during the late 1970s, feminist groups were only active within certain contexts, such as the church, as well as within literature, film, theater, and visual art circles. The 1980s opened up a variety of nonconformist gender images that contradicted stereotypical fixations. Richter particularly emphasizes the fact that during the 1980s, a renewed interest in antiquity in the arts activated iconic female figures such Penthesilea, Medea, or Cassandra, rebellious and emancipated women who attempted to defend themselves against the oppression and discrimination of patriarchal hegemony.

Having established the social context, Richter makes a “tiger’s leap into the past” in the spirit of Walter Benjamin, reconstructing the history of women artists in the GDR, a subject that has received little attention to date. She attends above all to critical artistic positions that question and make visible the construction of gender roles and attributes, as well as of gender hierarchies by exposing their structural conditions. With useful recourse to Judith Butler, a pioneer of the deconstruction of gender norms, Richter succeeds in revealing the ambivalence of the situation facing women in the GDR, and female artists in particular. She emphasizes the special position that women from the GDR—but also from other socialist countries in Eastern and Central Europe, as Richter repeatedly points out—took and continue to take within feminist discourse.

According to Richter, a feminist discourse as such, or a feminist movement in the true sense, did not exist in the GDR in the way it is known for the “West,” since many of the artists presented in the book also saw themselves as emancipated, not oppressed. Nevertheless, Richter demonstrates that specific academic programs of research into women’s issues established themselves in the GDR as well, albeit in isolated cases that were only institutionalized in late stages—but this was no different in the West. The volume of proceedings of the first (and at the same time last) conference of women art scholars in the East at the end of 1989 is considered by the academic world as an impressive testimony to the diversity of positions in women’s studies and feminist art history. The Center for Interdisciplinary Women’s Studies (now the Center for Transdisciplinary Gender Studies) at the Humboldt University in Berlin, founded by women scholars from the GDR in 1989, remains active to the present day. However, an East German-influenced women’s studies that both elaborates the emancipatory effects of women’s politics and criticizes the internal contradictions of gender relations in the GDR has not been established. In an effort to address this gap, Richter introduces these approaches into the feminist discourse, which continues to be dominated by the West. To blunt the West’s discursive hegemony, and to sensitize readers to the important emancipatory and empowering ideas and theories of women from the GDR, which are mostly ignored because they are misunderstood, Richter aims to expand and enrich contemporary feminist discourse.

To accomplish this, The Law of the Underground analyzes specific case studies: the female artists Karla Woisnitza, Gabriele Stötzer, Heike Stephan, Cornelia Schleime, and Yana Milev. These case studies explore individual artists’ performances and photographic (self-)stagings. Richter questions how the visual representation of women and its effects are reflected in specific works by these artists and how these representations pushed back against gender stereotypes. Richter underlines the key role of process-oriented art and intermediality for the emergence of alternative female corporeality beyond fixed gender identification or normative femininity.

One important case study that Richter discusses is the work of the Erfurt-based artist Gabriele Stötzer, whose archive was recently shown in several museum exhibitions (such as at the Gallery of Contemporary Art in Leipzig in 2019). Stötzer gathered a group of women and female artists around her who made photos, super-8 films, and paintings. United by their precarious situation as social dropouts and outsiders, they formulated alternative life concepts in their art, and in their practices of artistic collaboration and communal life. By exploring their naked bodies with great pleasure and joy in series of photos and in films, they created counterimages to the domesticized representations of women made by male artists of the first public sphere, creating new models for female identities. Stötzer also worked with punks and with queer men who identified as trans, as well as models who identified as neither feminine nor masculine. In the several images from her artist book Mackenbuch (the Book of Quirks), Stötzer photographs a crossdresser, a man who dresses in female clothes and shoes, who performs typically female poses on a chair. Posing for Stötzer, this crossdresser breaks up not only normative representations of femininity, but also of masculinity.

Richter herself belongs to the GDR’s so-called “Third Generation,” comprising those born in the 1970s. Her own biography as a child and adolescent shaped by the GDR—and then intellectually socialized in reunified Germany—remains largely unconsidered in the book, but her experience plays a supporting role as a background against which the author lays out her study. Through this book on the empowering and emancipatory actions of women artists, Richter extends these practices into the present precisely because she is also aware of her own subjective and contingent position as a researcher socialized in East Germany.

It is in this sense that The Law of the Underground performs the Benjaminian “tiger’s leap” mentioned above: Richter also opens up the possibility of reflecting on the situation of women in reunified Germany today precisely from the point of view of an Eastern-socialized woman. Although she demonstrates that women, and especially women artists, were not fully equal in the GDR, their position seemed utopian compared to the current debates that women have to face in reunified Germany. Specifically, the infrastructure of the care system was much more developed in GDR than it is reunified Germany. Reactionary perspectives (coming in particular from Bavaria) still tend to see women in the role of mothers, wives, and housewives. Women who dare to work and to be mothers are considered as bad mothers. Consequently, the few women who hold leading positions rarely have children. Richter’s book reminds us that policies regarding women in the GDR were progressive, despite all their failures. We can even say that this book not only explores a part of East German history that has been forgotten, but also that it describes artistic practices and feminist counterimages that could still serve as role models for the present and future. Further study of these women artists could enrich actual feminist debates by showing that the path to women’s emancipation did not have to follow the same trajectory popularized in the West.

As mentioned, Richter embeds the artistic positions and the theoretical debates in the GDR not only in an Eastern European context, but also in a Western European and American context, identifying many parallel structures. Since the art of the GDR has long been portrayed primarily in isolation from other objects of art-historical scholarship—or else as a belated counterpart to the Western part of divided Germany that has fallen out of time and failed to live up to its standards and aspirations—Richter’s approach is particularly important because it provides new perspectives on this art. It is true that the cultural exchange of women artists in the GDR with the other states of the former Eastern Bloc was rather marginal. This is something that Richter, and the research project Own Reality (which focused primarily on the cultural relations between the GDR and Poland)(See the website https://dfk-paris.org/de/ownreality.) both acknowledge. The interested gaze of East German artists was primarily directed at artistic developments on the other side of the Iron Curtain in the twin state of West Germany.

Nevertheless, Richter finds many similarities between the performances of Eastern European women artists and East German ones. For example, she compares the output of female East German performances, generally speaking, to the works of Polish artist Ewa Partum, who critically examines the subjugation of women in the institution of marriage. Threading insights from the work of artists like Partum into her investigations, Richter also contributes to the inclusion of art from the GDR in the discourse on Central, Eastern, and Southeastern European art of the state socialist era. Since East German art is comparatively understudied in this scholarship, Richter’s book helps art from the GDR to gain more visibility in an art historiography where it has been treated only with great restraint from both Western and Eastern European perspectives.

Finally, Richter’s book develops new approaches to the art of the GDR. Rather than record case studies in a purely empirical and thus almost positivistic manner, and line them up in a linear fashion, she subjects both discourses and artistic practices to an analysis guided by theory, one that is dedicated to and confronts the complexity—but also the contingency—of these same practices. In order to adopt a supposedly neutral stance towards the always-politically-charged and multi-layered artistic positions in the GDR (and in order to reconstruct and tell “the” single “true” story of the events) art historiography of the GDR has mostly dispensed with theoretical approaches. This makes one forget—as Richter contends, following Benjamin—that history is never a linear stringing together of events, but rather a collage-like, contradictory process that is always forming a new and constantly evolving. The author achieves her goal by analyzing the positions of female artists from the GDR in the context of current debates about performance art, critical questions about the representation of women, the construction of gender identities in gender studies, questions of power according to Foucault, and the issue of access to the public sphere and its definition. This allows her to speak “affirmatively” about this art, in the sense that Butler describes as “opening up the possibility of agency.”

Angelika Richter’s The Law of the Underground is thus an important contribution to bringing the historiography of art from the GDR to a new scholarly level and, above all, to giving the practices of women artists from the GDR a new publicity and visibility. Works by these artists are unfortunately still underrepresented even in collections, a situation that will hopefully change as more curators and scholars begin to explore the interrelated ideas, critical positions, and shared histories that Richter presents.