Why Sports and Art Go Well Together: A Conversation with Przemysław Strożek (Warsaw)

Katalin Cseh-Varga and Kristóf Nagy started working on the interrelation of sport and neo-avant-garde in January 2016, based on an in-depth research of Hungarian painter László Lakner’s Foot Art project (1970), which was further developed into an exhibition-action draft by art organiser László Beke designed for documenta 5 (1972). During the intense research period in June 2016 the European Network for Avant-Garde and Modernism Studies arranged two conference sessions on Avant-Garde and Sport in the framework of which Katalin got acquainted with the work of Przemysław Strożek who at that time talked about the world cup of 1934, politics, art and physical culture in fascist Italy. This encounter was the beginning of a lively academic exchange on the relevance of sports for non-conformist art in Central Europe and beyond.

Katalin Cseh-Varga – Kristóf Nagy: In your current research you are focusing on responses by former Czechoslovakian and Soviet artists to the so-called Workers’ Olympics. Why do you think the enthusiasm for sports was so significant for avant-gardists?

Przemysław Strożek: After the geopolitical shifts following 1918 and the establishment of new countries in Central and Eastern Europe, avant-garde trends flourished in the region primarily within leftist artistic circles who were drawn into the ideas of internationalism and who were inspired, in a greater part, by Constructivist trends in Soviet Russia. Artists from the radical wing of Constructivism from Poland, Hungary, Czechoslovakia, Romania and Yugoslavia recognized their social role as “constructors” of the new post-1918 reality. They connected new art with leftist ideologies and promoted the idea of working-class struggle. 1920’s Constructivism linked the concepts of cultural modernity to art’s renewal for social needs. In this context sport started to become one of the most important social phenomena and a sign of modernization. Seeking to establish the foundations for a new proletarian culture, the Constructivists enthusiastically responded to the idea of creating new public spaces for physical activity, such as sports grounds, stadiums and other recreational grounds. They promoted wellbeing and a healthy lifestyle because “to construct” meant to “organize life” by means of new architecture; or, more directly: it meant to “organize life” according to the proletariat´s social needs.

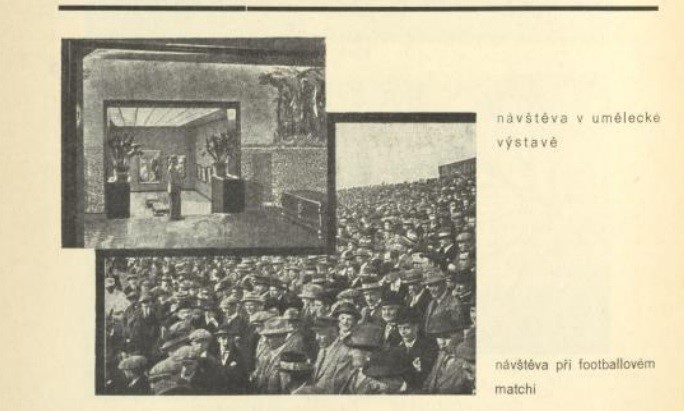

Stadiums and sporting grounds had the function of replacing museums, while sports meant replacing traditional, “bourgeois” art. It is worth quoting here the Swiss architect Hannes Meyer who was a member of the ABC group that introduced Russian Constructivist architecture in the West. In 1926 he wrote: “The stadium vanquishes the art museum and bodily reality has taken the place of beautiful illusion.”(Hannes Meyer, “Die Neue Welt”, Das Werk 7 (1926): 27, 185.) There is an interesting photomontage published inthe Czechoslovakian Constructivist magazine called RED. We can find there a juxtaposition of two photographs. One photograph is showing the audience of an art exhibition, and the other one the audience at a football game. At the museum we see only one person contemplating artworks, whereas at the stadium there is a huge crowd gathered watching the sports spectacle. This image expresses a clear message: in terms of its impact on the masses, the art exhibition is something inferior compared to a stadium game. To reject the “bourgeois” tradition and to move art towards social and proletarian needs was at the core of the Constructivists’ radical program. Sports suited these ideas very well.

KCSV-KN: In the 1920s and ‘30s many leftist artists from our region were inspired by sports. Was this enthusiasm towards sports entirely homogeneous?

PS: I have referred to Russian and Czechoslovakian Constructivists because they were most involved in the Red Sport International (RSI) propaganda. RSI was a Communist organization established in 1921 to unite sport and politics, with an aim to support international class struggle and to create new ideals for workers´ culture. RSI organized the so-called Spartakiads, which were supposed to be directed explicitly against all chauvinism, racism, sexism, and social exclusivity, and which were organized for the enjoyment of working class women and men. When we look at Eastern Europe, the RSI did not establish branches outside of Russia and Czechoslovakia. I would say that the enthusiasm for RSI activity within the radical wing of the Russian and Czechoslovak Constructivists was homogenous in terms of workers’ cultural propaganda. The RSI had over 2 million members and was the biggest workers’ cultural movement. More “moderate” avant-garde artists from the region may not have supported the RSI that much, but rather the idea of workers´ sports in general. I learned from Anna Juhász, the curator of the Kassák Museum Budapest, that Hungarian avant-garde magazines such as 100% or Munka [Work] were just as enthusiastic about workers´ sports. In Poland, this enthusiasm was weaker. It is interesting that Mieczys?aw Szczuka, the leader of the Polish Constructivists, was a very skilled sportsman, a mountaineer, who discovered new routes in the Tatra Mountains. Unfortunately, he died climbing the most dangerous route of Zamar?a Turnia in 1927. He was a sports enthusiast, but in a different way: he never paid much attention to sports mass spectacles, and he was not really involved in class-struggle-propaganda through sport. He was very much involved, however, in the activities of the Polish Communist Party although, he never connected his sporting activities to a political agenda.

KCSV-KN: In a number of your presentations/publications you combine the three “pillars” of politics, sports, and the (historical) avant-garde. How do these three seemingly different fields come together, and could you give us any examples where we can study their interrelation?

PS: Sport has almost always been, and in fact still is, about politics and about cultural and visual propaganda. Even nowadays artists are responding to these connections. Just recall the case of Ai Weiwei who was the artistic consultant of the Stadium in Beijing for the Olympics in 2008 and, this way, supported the Chinese government’s propaganda. Sport is almost always about showing a kind of soft-power strategy. Take the case of the avant garde leftwing artists from Russia and Czechoslovakia who were involved in RSI and Communist propaganda. However, we can trace the politics of sport also to the artworks supported by Italian Fascism or German Nazism. Especially in the 1930s the promotion of sports was very important for these right-wing governments, and artists responded to that. But the governments’ approach towards visual sport propaganda was far more related to the promotion of a country’s accomplishments at the Olympic Games. Workers´ sport movements accused the International Olympic Committee of being fascist. And they were right: among the Olympic founding fathers many had racist views including even the founder of the modern Olympic movement, Baron Pierre de Coubertin, and the 1936 Olympics were after all awarded to Nazi Germany. Artists from Germany created many artworks related to sports, but in a very different manner from the RSI propaganda. They focused more on athletics and the revival of ancient Greek art, whereas the Constructivists had focused on visual propaganda through new media. The 1936 Berlin Olympics were the last important international event organized in the German capital before the war. The objective of the event was also to show the “new” Germany as an open country. How much Germany was “open” in 1936 is illustrated by the fact that the Olympic art competition included even avant-garde artworks. Only a year later, in 1937, avant-garde would be qualified as “degenerate”. And we cannot forget that Leni Riefenstahl’s Olympia (1936) documentary was one of the most recognizable Nazi propaganda films. It was in fact based on the innovations in filmmaking introduced by Russian Constructivists and the German avant-garde. It is interesting to look at the way in which various nationalisms included avant-garde experiments in their propaganda. In both cases, politics, sport and art are being merged.

KCSV-KN: You have written about the political differences that divided the right from the left avant-garde—the Futurists from the Constructivists—when it came to the relationship between art and sport. Was this division more fundamental than the one between traditional artists and the avant-garde in this regard, or not?

KCSV-KN: You have written about the political differences that divided the right from the left avant-garde—the Futurists from the Constructivists—when it came to the relationship between art and sport. Was this division more fundamental than the one between traditional artists and the avant-garde in this regard, or not?

PS: For both left-wing and right-wing avant-gardists, sports was an issue of both of modernity and physical culture propaganda alike. The Italian Futurists who promoted fascist politics in the 1930s were also sports enthusiasts, but in a different way from the Constructivists connected to the RSI. These divisions are especially visible in the use of materials: for example, the Futurists promoted soccer, “the national Fascist game,” (Simon Martin, Football and Fascism: The National Game Under Mussolini, (London: Bloomsbury, 2004), 221.) and worked with traditional genres such as painting and sculpture. Avant-garde artists from the radical wing of Constructivists, on the other hand, focused on sports propaganda as a way of supporting working-class struggle in a new media format (photography, photomontage). Both groups recognized the importance of sports and its visual representation, but for different political aims and in different form. For example Enrico Prampolini’s painting Angels of Earth from 1936 expressed a vision of a football match that brought together the 1930s Futurist aesthetic and the ideology of Fascist propaganda. All that is national, masculine, modern, victorious and dynamic is here being related to the aspects of new spiritualism and cosmic reality in the form of the Football match. The angel footballers are hovering above the map of their home country where the victorious tournament took place, while players such as Giuseppe Meazza, Gianpiero Combi, and Raimundo Orsi became the idols of cheering Italian crowds.

KCSV-KN: You have discussed both the liberating and the disciplining functions of sport, which are also reflected in avant-garde artworks related to sports. How do these two functions relate to each other?

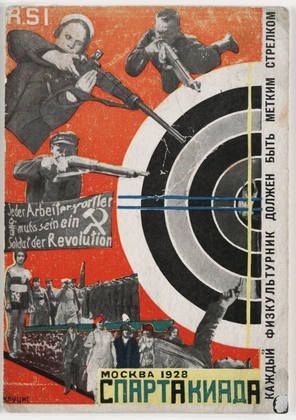

PS: Gymnastics, for instance, can be seen as a liberation of the body through innovative dance experiments—also as a liberation of women’s bodies—, but it can also be a disciplining force, for example when it is connected to military training. Avant-garde artists were interested in both of these possibilities. Gustav Klutsis writes on one of his Spartakiad postcards: “Every worker-sportsman must be a soldier of the revolution.”(Gustav Klutsis, Postcard for the All Union Spartakiada Sporting Event, 1928, Courtesy of the Museum of Modern Art New York, https://www.icp.org/icpmedia/k/l/u/t/klutsis_gustav_2012_64_6_448919_thumbnail.jpg, last accessed: January 17, 2017.) Sports had the role of training the proletariat for class struggle. On the other hand, other postcards carried the inscription “Physical education is one of the links in the Soviet cultural revolution.”(Klutsis, Postcard for the All Union Spartakiada Sporting Event, 1928, https://www.moma.org/collection/works/7031?locale=en, last accessed: January 22, 2017.) Women and men were to have equal positions, they competed together, and even their clothes were more and more unisex.

PS: Gymnastics, for instance, can be seen as a liberation of the body through innovative dance experiments—also as a liberation of women’s bodies—, but it can also be a disciplining force, for example when it is connected to military training. Avant-garde artists were interested in both of these possibilities. Gustav Klutsis writes on one of his Spartakiad postcards: “Every worker-sportsman must be a soldier of the revolution.”(Gustav Klutsis, Postcard for the All Union Spartakiada Sporting Event, 1928, Courtesy of the Museum of Modern Art New York, https://www.icp.org/icpmedia/k/l/u/t/klutsis_gustav_2012_64_6_448919_thumbnail.jpg, last accessed: January 17, 2017.) Sports had the role of training the proletariat for class struggle. On the other hand, other postcards carried the inscription “Physical education is one of the links in the Soviet cultural revolution.”(Klutsis, Postcard for the All Union Spartakiada Sporting Event, 1928, https://www.moma.org/collection/works/7031?locale=en, last accessed: January 22, 2017.) Women and men were to have equal positions, they competed together, and even their clothes were more and more unisex.

KCSV-KN: It is becoming clear that the idea of nation (politics) and the community-building force inscribed into e.g. football have a lot in common. The same is true for many of the artistic adaptations about which you have written. Have you ever thought about the gender discourse inscribed into artworks dealing with, say, soccer? Can you think of any Polish cases?

PS: The gender discourse in visual representations of sports is very important. It is worth mentioning how many women were involved in painting sports motifs. In Poland the most significant and known sculptures of boxers in the 1930s were created by Olga Niewska, while Maria Ewa ?unkiewicz Rogoyska painted big canvases showing soccer players, and Janina Konarska gained a medal for her graphics on a soccer game at the Olympics in Los Angeles.

When thinking about gender and football I always have in my mind a great piece by Zdzis?aw Sosnowski that was made decades later than the historical avant-garde pieces we were discussing before. In the mid-1970s he shot a film entitled The Goalkeeper. Sosnowski portrayed himself as the soccer player, as a celebrity adored by young and beautiful women. During the sporting training the goalkeeper seduces them but they exploit him, too, wrestling with him in his fight for the ball. When the goalkeeper lies on the pitch, the women tread on him with only their legs—in thin black tights and black, high-heeled shoes—visible in the frame. The woman’s role is reduced here to the role of an aggressor who rhythmically kicks the ball held by the goalkeeper. In one of the scenes the entangled bodies of a woman and the goalie are  separated only by a ball that is being pushed by both of them, in a manner reminiscent of lovers’ sexual gestures. The ball becomes the vehicle by which their sexual relations are mediated. Thereby, Sosnowski transforms the sporting game into an erotic one. This happens in order to examine masculinity in the context of man-woman relationships, erotic fantasies, and sports. This is what interests me most: not sports in art per se, but a critical approach towards society, politics, and the world that 20th-century artists mediate through their works related to sports.

separated only by a ball that is being pushed by both of them, in a manner reminiscent of lovers’ sexual gestures. The ball becomes the vehicle by which their sexual relations are mediated. Thereby, Sosnowski transforms the sporting game into an erotic one. This happens in order to examine masculinity in the context of man-woman relationships, erotic fantasies, and sports. This is what interests me most: not sports in art per se, but a critical approach towards society, politics, and the world that 20th-century artists mediate through their works related to sports.

KCSV-KN: Thank you for this conversation.

Budapest, October 2016.

Przemysław Strożek completed an MA at the University of Warsaw (Polish Studies); MA at Theatre Academy in Warsaw (Theatre Studies) and PHD at the Institute of Art of the Polish Academy of Sciences in Warsaw. He is a lecturer at Academy of Fine Arts in Warsaw (Graphic Design Faculty), a lecturer at Collegium Civitas is Warsaw (Cultural Studies) and a 2012/2013 Fulbright Visiting Scholar at The University of Georgia (Modernist Studies). He is a member of the European Network for Avantgarde and Modernist Studies and focuses his research on avant-garde and popular culture. He has authored several studies on Avant-garde, Polish modern and contemporary art.

Przemysław Strożek completed an MA at the University of Warsaw (Polish Studies); MA at Theatre Academy in Warsaw (Theatre Studies) and PHD at the Institute of Art of the Polish Academy of Sciences in Warsaw. He is a lecturer at Academy of Fine Arts in Warsaw (Graphic Design Faculty), a lecturer at Collegium Civitas is Warsaw (Cultural Studies) and a 2012/2013 Fulbright Visiting Scholar at The University of Georgia (Modernist Studies). He is a member of the European Network for Avantgarde and Modernist Studies and focuses his research on avant-garde and popular culture. He has authored several studies on Avant-garde, Polish modern and contemporary art. Katalin Cseh-Varga holds a Master’s degree (2010) in Theatre, Film and Media Studies from the University of Vienna. She is currently working as a research assistant at the Graduate School of East and Southeast European Studies at the Ludwig-Maximilians-University in Munich and as a lecturer at the Department of Theatre, Film and Media Studies at the University of Vienna. In June 2016 Katalin successfully defended her doctoral dissertation entitled “Rebelling (Play)Spaces and Underground Networks. The ‘Second Public Sphere’ of the Hungarian Avant-Garde”. She is a member of the Young Academic’s Network “Action Art Beyond the Iron Curtain” funded by the German Research Society (DFG). Katalin presents and publishes extensively on the theory of public spheres in the former Eastern Bloc, creative practices of Hungarian samizdat respectively archiving, performative and medial spaces of the Hungarian experimental art scene in the period of the late 1960s to the early 1990s.

Katalin Cseh-Varga holds a Master’s degree (2010) in Theatre, Film and Media Studies from the University of Vienna. She is currently working as a research assistant at the Graduate School of East and Southeast European Studies at the Ludwig-Maximilians-University in Munich and as a lecturer at the Department of Theatre, Film and Media Studies at the University of Vienna. In June 2016 Katalin successfully defended her doctoral dissertation entitled “Rebelling (Play)Spaces and Underground Networks. The ‘Second Public Sphere’ of the Hungarian Avant-Garde”. She is a member of the Young Academic’s Network “Action Art Beyond the Iron Curtain” funded by the German Research Society (DFG). Katalin presents and publishes extensively on the theory of public spheres in the former Eastern Bloc, creative practices of Hungarian samizdat respectively archiving, performative and medial spaces of the Hungarian experimental art scene in the period of the late 1960s to the early 1990s. Kristóf Nagy completed his MA in 2015 at The Courtauld Institute of Art in the Special Option Countercultures: Alternative Art in Eastern Europe and Latin America. His BA dissertation was published in Hungarian and will be included in the forthcoming volume East-Central European Art from Global Perspectives: Past and Present. He is currently completing his second MA in Sociology and Social Anthropology at the Central European University and works at the Artpool Art Research Center as a research fellow. His research primarily focuses on the intersections of artistic and social issues since the 1970s, and he presented them in several conferences, such as Eastern Europe in a Global Perspective in Lublin, AAH in Norwich or IKT in Vienna.

Kristóf Nagy completed his MA in 2015 at The Courtauld Institute of Art in the Special Option Countercultures: Alternative Art in Eastern Europe and Latin America. His BA dissertation was published in Hungarian and will be included in the forthcoming volume East-Central European Art from Global Perspectives: Past and Present. He is currently completing his second MA in Sociology and Social Anthropology at the Central European University and works at the Artpool Art Research Center as a research fellow. His research primarily focuses on the intersections of artistic and social issues since the 1970s, and he presented them in several conferences, such as Eastern Europe in a Global Perspective in Lublin, AAH in Norwich or IKT in Vienna.