Unrecounted: Historical Amnesia in Germany and Namibia at the Venice Biennale 2015

Unrecounted: Historical Amnesia in Germany and Namibia at the Venice Biennale 2015, May 4-9, 2015, Conservatorio Benedetto Marcello, Palazzo Pisani, Venice

After Angola won the Golden Lion for best national pavilion upon its first participation in the Venice Biennale in 2013, Okwui Enwezor’s edition of the Biennale in 2015 further emphasized the African context. With the exception of the debacle surrounding the Kenyan pavilion, which was disowned by the Kenyan government because the artists chosen to participate, grotesquely, were once again, as in 2013, mostly Chinese, Enwezor’s curatorial lead meant that artists from the margins were finally given greater visibility.(Laura C. Mallonee, “Kenyan Government Denounces the Country’s Venice Biennale Pavilion,” Hyperallergic, April 24, 2015, http://hyperallergic.com/201564/kenyan-government-denounces-the-countrys-venice-biennale-pavilion/.) But Enwezor’s Biennale also attracted artistic and curatorial projects in which artists of European descent owned up to their inherited legacy of the colonizer, raising difficult questions about what it meant to speak from this perspective, and, more broadly, about how the different voices were situated in relation to one another.

Among the unofficial fringe events in Venice during the Biennale’s opening week was a small thematic exhibition held in the Palazzo Pisani, which also hosted the Angolan Pavilion, focused on the history of German colonialism in Namibia. Entitled Unrecounted (with a nod to W. G. Sebald), the exhibition paired two time-based works by artists of German heritage: Christoph Schlingensief (1960-2010), whose work for the German Pavilion had been posthumously awarded the Golden Lion for best national participation in 2011; and Nicola Brandt (born Windhoek, 1983), who recently had a solo exhibition at the National Art Gallery of Namibia, which also supported the Venice Biennale exhibition.(Nicola Brandt, The Earth Inside, National Art Gallery of Namibia, 2014.) (In the aftermath of German colonialism and then South African apartheid policy until 1990, Namibia has yet to institute a national pavilion.) Their work not only explored visual art’s capacity for and limitations in dealing with unspeakable history and repressed trauma, but also addressed historical responsibility and the dilemmas presented by the inherited perspective of the perpetrator – to confront the ghosts from the past by undertaking what T. J. Demos has referred to as a “return to the postcolony” without, however, recreating problematic power relations.(T. J. Demos, Return to the Postcolony: Specters of Colonialism in Contemporary Art (Berlin: Sternberg Press, 2013).)

In the Unrecounted exhibition, this meant the artists coming to terms with their own culture’s denials, the discourses that underpinned the colonial project, and the legacies of these discourses in the present situation. Organized by an international team of curators—Sarah Hegenbart from Germany, Vid Simoniti from Slovenia, and Adina Drinceanu from Romania—whose collective interests in the exhibition project converged around romanticism and repressed histories, the exhibition contributed to rich existing discourses about the relation between romanticism and imperialism, while also bringing an awareness to a part of colonial history that has often been overlooked. Whereas in Namibia, the traumas caused by the colonial past and the genocide committed by the Germans from 1904 to 1908 have carried across generations (while official memory work has largely been lacking), this history is only just starting to become part of collective consciousness in Germany, where it has been blocked from view by the magnitude of the crimes inflicted afterwards, two world wars and the Holocaust. In fact, it is only now, a century after the end of German colonial rule in Namibia, that the German government has acknowledged the massacre of the Herero and Nama to be “genocide.”(“Bundestagspräsident Lammert nennt Massaker an Herero Völkermord,” Die Zeit, July 8, 2015, http://www.zeit.de/politik/deutschland/2015-07/herero-nama-voelkermord-deutschland-norbert-lammert-joachim-gauck-kolonialzeit.) As Germany plans to address its colonial past within the institutional context of the future Humboldt Forum – a planned presentation of its ethnographic collections in a yet to be completed, contested reconstruction of a baroque castle in Berlin – questions about collective memory and the construction of identity, and about romanticism and reconciliation that were dealt with in the Unrecounted exhibition are not only timely, but also part of a much larger conversation.(On the Humboldt Forum, see Michael Scaturro, “Berlin’s rebuilt Prussian palace to address long-ignored colonial atrocities,” The Guardian, May 18, 2015, http://www.theguardian.com/world/2015/may/18/berlins-rebuilt-prussian-palace-to-address-long-ignored-colonial-atrocities.)

The different problematics of memory culture in Germany and Namibia, respectively, were reflected in the works by the two artists, whose deployments of the moving image also present different ways of dealing with traumatic history and the “return to the postcolony.” While Schlingensief is an artist with a background in time-based media, whose nonlinear, often impolite installation works push disciplinary boundaries and whose search for a new energy in art and dissatisfaction with Western capitalist culture has led him to repeatedly visit Africa, Brandt’s video work with loosely narrative and partly fictional elements recasts the legacy of South African and Namibian documentary photography to create more emotive multimedia work as she returns to her home country to find a place haunted by ghosts from the past.

In Schlingensief’s The African Twin Towers (2005-2009), projected in Venice as a single-channel 70-minute film, the confrontation with the former colony and traumatic memory spurs a narrative breakdown that manifests as a daybook of fragments about the equally fragmented Fitzcarraldo-esque attempt of staging Richard Wagner’s Ring Cycle in a township in Namibia, presented with a retrospective voiceover commentary.(An overview of the different versions of The African Twintowers is provided by the distributing gallery at http://www.filmgalerie451.de/filme/the-african-twintowers.) In Werner Herzog’s 1982 film Fitzcarraldo, the opera lover’s feverish and ultimately failed romantic vision was to transform the world by building an opera house in Peru – even, or especially as that involved hauling a steamship over a mountain in the Amazon rainforest. However, it was the European conception of opera itself that Schlingensief strove to transform (along with Herzog’s narrative film practice), reinvigorating it from the elitism epitomized by the Bayreuth Festival in Germany.(For Schlingensief’s own account of his aims to reinvigorate traditional opera, see his mission statement for the Opera Village Africa in Burkina Faso (2010-). “Unsere Oper ist ein Dorf” can be accessed at http://www.operndorf-afrika.com/index.php/das-projekt/articles/unsere-oper-ist-ein-dorf.html. In the Unrecounted exhibition, documentary material about the Opera Village Africa conveyed a sense of the scope and progress of this ongoing project, which brings together European opera and everyday life in Africa, while seeking to overcome the hegemonic implications of development practice.)

In Schlingensief’s The African Twin Towers (2005-2009), projected in Venice as a single-channel 70-minute film, the confrontation with the former colony and traumatic memory spurs a narrative breakdown that manifests as a daybook of fragments about the equally fragmented Fitzcarraldo-esque attempt of staging Richard Wagner’s Ring Cycle in a township in Namibia, presented with a retrospective voiceover commentary.(An overview of the different versions of The African Twintowers is provided by the distributing gallery at http://www.filmgalerie451.de/filme/the-african-twintowers.) In Werner Herzog’s 1982 film Fitzcarraldo, the opera lover’s feverish and ultimately failed romantic vision was to transform the world by building an opera house in Peru – even, or especially as that involved hauling a steamship over a mountain in the Amazon rainforest. However, it was the European conception of opera itself that Schlingensief strove to transform (along with Herzog’s narrative film practice), reinvigorating it from the elitism epitomized by the Bayreuth Festival in Germany.(For Schlingensief’s own account of his aims to reinvigorate traditional opera, see his mission statement for the Opera Village Africa in Burkina Faso (2010-). “Unsere Oper ist ein Dorf” can be accessed at http://www.operndorf-afrika.com/index.php/das-projekt/articles/unsere-oper-ist-ein-dorf.html. In the Unrecounted exhibition, documentary material about the Opera Village Africa conveyed a sense of the scope and progress of this ongoing project, which brings together European opera and everyday life in Africa, while seeking to overcome the hegemonic implications of development practice.)

The Fitzcarraldo theme of transporting culture provided a point of reference for artists at the Polish Pavilion as well, where the theme was differently interpreted to reflect the fact that Polish soldiers in Haiti defected from the French colonial army in the fight for independence. A joint film project about the staging of a Polish opera in Haiti by the artists in the Polish pavilion, C. T. Jasper and Joanna Malinowska, Halka/Haiti 18°48’05?N 72°23’01?W (2015), by the latter’s account was based on the “decision to realize Fitzcarraldo’s obsession, to succeed where he failed.”(The pavilion was curated by Magdalena Moskalewicz. See Lilly Wei, “Poland’s Venice Pavilion Explores Haiti’s Polish Connection,” ARTnews, April 29, 2015, http://www.artnews.com/2015/04/29/polands-venice-pavilion-explores-haitian-polish-connection.) By contrast, Schlingensief didn’t try to succeed where Fitzcarraldo failed but raised the stakes – “hauling the mountain over the steamship” is how he put it in the film. Here, the artist suggests the sense of inadequacy of any response he might provide to the suffering inflicted by Germany’s colonial history, a history that, while hardly addressed directly in the film, confronts the viewer throughout in the form of utter chaos.(All translations from the German are by the author.)

Schlingensief’s film is effectively an absurdist theater of indefinite meanings in which the script is conveniently stolen first thing, leaving his motley cast of actors to reenact other scripts, conjure Nordic myths, and experiment with psychedelics. Meanwhile there is news of his father back in Germany having suffered a stroke, and Patti Smith shows up in the desert at random. For much of the film, it remains unclear what is fiction and what is not, adding to the viewer’s sense of disorientation, yet the physical and mental exertion of Schlingensief and his crew is beyond doubt. While a twin-masted ship is ultimately lifted onto a rotating stage in the township of Lüderitz to provide a platform for locals and their stories, in Schlingensief’s film, the emphasis, rather than on collecting these stories, is instead on rendering the German crew ridiculous. Following a casting scene in which local residents and the German casting crew have an encounter that leaves the viewer feeling uncomfortable, Schlingensief ruminates: “Perhaps the Africans know better what the Germans are doing in Namibia than the Germans themselves.” In The African Twintowers, for the Germans, confronting the legacies of colonialism’s politics of otherness means confronting their own psychic otherness – a process, which holds the potential for creating some level of understanding between the descendants of former colonizers and former colonial subjects.

Schlingensief’s film is effectively an absurdist theater of indefinite meanings in which the script is conveniently stolen first thing, leaving his motley cast of actors to reenact other scripts, conjure Nordic myths, and experiment with psychedelics. Meanwhile there is news of his father back in Germany having suffered a stroke, and Patti Smith shows up in the desert at random. For much of the film, it remains unclear what is fiction and what is not, adding to the viewer’s sense of disorientation, yet the physical and mental exertion of Schlingensief and his crew is beyond doubt. While a twin-masted ship is ultimately lifted onto a rotating stage in the township of Lüderitz to provide a platform for locals and their stories, in Schlingensief’s film, the emphasis, rather than on collecting these stories, is instead on rendering the German crew ridiculous. Following a casting scene in which local residents and the German casting crew have an encounter that leaves the viewer feeling uncomfortable, Schlingensief ruminates: “Perhaps the Africans know better what the Germans are doing in Namibia than the Germans themselves.” In The African Twintowers, for the Germans, confronting the legacies of colonialism’s politics of otherness means confronting their own psychic otherness – a process, which holds the potential for creating some level of understanding between the descendants of former colonizers and former colonial subjects.

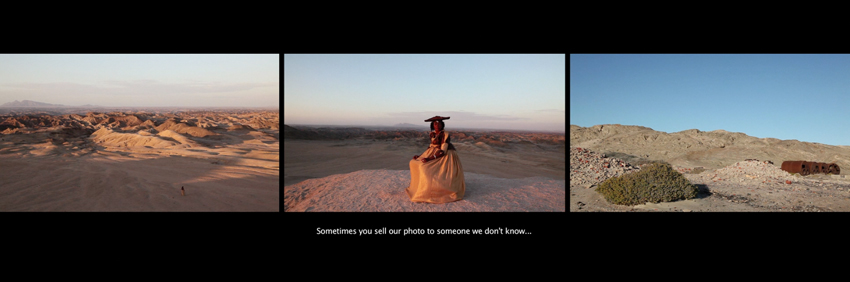

If Schlingensief, arriving in Namibia from Germany, engages the problematics of otherness (his trip to Namibia was itself part of the film on display),(At the start of the film, we see him sporting a cowboy hat together with the most unlikely, dressed up crew of German actors arrive at the airport in Windhoek, where they are welcomed like tourists by a local music group – a scene that immediately raises issues of hegemony and authenticity, but by virtue of the German’s own carnival dispels the concerns about exoticism that a European film project in Namibia might bring up.) for Brandt, having grown up in Namibia, it is in the first instance one of memory. Her video Indifference (2014) captures something of the multiplicity of subjective experiences that exist beyond the archival record and that get related orally. Indifference, a three-channel, fourteen-minute video, features women of three generations against the background of metaphorically charged landscapes and interior spaces. One is a Herero woman, who finds herself reminded of the Herero and Nama genocide as she goes about her daily business, sporting the traditional Herero dress for tourists in the outback. An older German woman, only present through her voiceover, talks nostalgically about romance and the past while visiting a cemetery; a younger German woman, who in a kind of reverse mimicry, is clad in traditional Herero dress, does not speak, but her silence suggests the presence of inherited feelings of guilt and shame. In Brandt’s video, her use of nonlinear narrative mimics the ways in which memory itself works and trauma is transmitted from one generation to the next. Accompanied by classical music, the video appeals to what Jill Bennett has theorized as “empathic vision,” an understanding of trauma derived from sensuous, affective qualities; that is, an empathic relation to lived experience more than objective contextual information.(Jill Bennett, Empathic Vision: Affect, Trauma, and Contemporary Art (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2005).)

If Schlingensief, arriving in Namibia from Germany, engages the problematics of otherness (his trip to Namibia was itself part of the film on display),(At the start of the film, we see him sporting a cowboy hat together with the most unlikely, dressed up crew of German actors arrive at the airport in Windhoek, where they are welcomed like tourists by a local music group – a scene that immediately raises issues of hegemony and authenticity, but by virtue of the German’s own carnival dispels the concerns about exoticism that a European film project in Namibia might bring up.) for Brandt, having grown up in Namibia, it is in the first instance one of memory. Her video Indifference (2014) captures something of the multiplicity of subjective experiences that exist beyond the archival record and that get related orally. Indifference, a three-channel, fourteen-minute video, features women of three generations against the background of metaphorically charged landscapes and interior spaces. One is a Herero woman, who finds herself reminded of the Herero and Nama genocide as she goes about her daily business, sporting the traditional Herero dress for tourists in the outback. An older German woman, only present through her voiceover, talks nostalgically about romance and the past while visiting a cemetery; a younger German woman, who in a kind of reverse mimicry, is clad in traditional Herero dress, does not speak, but her silence suggests the presence of inherited feelings of guilt and shame. In Brandt’s video, her use of nonlinear narrative mimics the ways in which memory itself works and trauma is transmitted from one generation to the next. Accompanied by classical music, the video appeals to what Jill Bennett has theorized as “empathic vision,” an understanding of trauma derived from sensuous, affective qualities; that is, an empathic relation to lived experience more than objective contextual information.(Jill Bennett, Empathic Vision: Affect, Trauma, and Contemporary Art (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2005).)

By addressing viewers on an affective level, Brandt gives a visceral sense of the specters of history. Her video seduces the viewer by mobilizing the aesthetics of German Romanticism and the sublime, but ultimately only to deconstruct their ideologies of unoccupied territory. The landscapes, which the Herero woman passes through, are awe-inspiring, both beautiful and vast, but also haunted by history and implicated in present-day politics of gender, race, and social class. In one of the opening scenes that takes place in Lüderitz, a new railroad track is being built alongside unmarked mass graves. The proximity of the railroad tracks to the mass graves and the absence of a historical marker signify a lack of concern for the traumas incurred by the country’s Herero and Nama minorities. As her way to work leads her past another set of unmarked mass graves in Swakopmund, the Herero woman’s narrative does not so much recall the past as conjure its presence in everyday experience.

Providing a platform for a suppressed Herero voice goes hand in hand with exposing the prejudice and denial still present in the German-Namibian population to this day. The vast, immersive landscapes that unfold across three screens are recurrently interrupted by a close-up shot of a bookshelf that provides the backdrop for the older German woman’s voice. While at first the book spines and the sentimental trinkets decorating the shelf create a haptic experience of the German-Namibian household, the viewer eventually spots – among books by authors such as Stefan Zweig – Adolf Hitler’s Mein Kampf. It is the shock of the book and the shift from a sensuous to a more contextual mode of engagement with questions about historical connections between Nazism and German colonialism that makes this moment in the video so particularly powerful.

Both works in the Unrecounted exhibition deal with repressed history, but rather than representing it, they affectively invite a response to its legacies that continue to haunt the descendants of victims and perpetrators. By withholding an objective account of this history, Brandt’s video challenges the viewer to engage with the two voices (one German-Namibian, the other Herero), and when confronted with disturbing material, to enter into a position of moral responsibility. By contrast, Schlingensief provides commentary throughout his film, but also avoids any sense of didacticism or a firm conclusion. His disorienting and often discomforting film stirs up viewers to actively engage on a moral level and positions itself in opposition not only to stupefying and manipulative mass media formats, but also to a memory culture in which concern ends up solidified in stone memorials.

Both works in the Unrecounted exhibition deal with repressed history, but rather than representing it, they affectively invite a response to its legacies that continue to haunt the descendants of victims and perpetrators. By withholding an objective account of this history, Brandt’s video challenges the viewer to engage with the two voices (one German-Namibian, the other Herero), and when confronted with disturbing material, to enter into a position of moral responsibility. By contrast, Schlingensief provides commentary throughout his film, but also avoids any sense of didacticism or a firm conclusion. His disorienting and often discomforting film stirs up viewers to actively engage on a moral level and positions itself in opposition not only to stupefying and manipulative mass media formats, but also to a memory culture in which concern ends up solidified in stone memorials.

As artists face up to repressed history by undertaking a “return to the postcolony,” they run the risk of recreating or reinforcing problematic power relations. For Schlingensief, playing with this risk is part of his artistic strategy of provoking a moral reaction in the viewer. In Brandt’s work, she builds relationships with the Herero woman, Uakondjisa Kakuekuee Mbari, and, in another series of photographs, with Katuvangua Migal Maendo, with whom she has collaborated since 2012. When Uakondjisa Kakuekuee Mbari in Brandt’s video Indifference addresses the commodification of her own image by tourists, Brandt’s video self-critically reflects on the difficult issues of representation and power as they can pertain also to artistic practice. Such work invites viewers to imagine a different future as they confront a traumatic past. In the case of the Unrecounted exhibition, it may even set a precedent for a Namibian pavilion in Venice, in which previously suppressed voices may be heard in the future and new relations forged.