The Queer Story of Polish Art and Subjectivity

“A new spectre is haunting Eastern Europe: the spectre of sexual and love dissidence.”Tomek Kitlinski, Pawel Leszkowicz, Love and Democracy. Reflections on the Homosexual Question in Poland, Aureus, Krakow, 2005, s. 290-291.

At the dawn of the new millennium, Poland and Eastern Europe face the task of discovering a new all-embracing culture, and of writing a new, affirmative history of diversified and plural stories of love and sexual identities and their cultural representations. After decades of censorship, discrimination, and homophobia, the time has come to discover the complex amorous subjectivity in Polish contemporary society and art.

To embrace such a project is to humanise culture and to open the area of expression and knowledge to all kinds of sexual identities and to oppose the fundamentalist intolerance and ignorance. To embrace such a project is to understand fully what it means to be human in its multiplicity, queerness, cultural variety and sensual pleasures. The new culture in Eastern Europe would be a response to the ethics of human rights and the politics of diversity and social justice.

The text will be concerned primarily with the story of Polish art since the 1970s, yet hopefully its perspective might be relevant for other spheres of culture and inspire similar rediscovery in other post-communist countries grappling with democracy. The examples of curatorial and artistic interventions into Poland’s heteronormativityAccording to Samuel Chambers, “the term “heteronormativity” was coined by Michael Warner (1993), but its roots extend back to Adrienne Rich’s (1980) famous argument about “compulsory heterosexuality”. Some define heteronormativity as a practice of organising patterns of thought, awareness and beliefs around the presumption of universal heterosexual desire, behaviour and identity, while other definitions emphasize either the rule that force us to conform to hegemonic heterosexual standards or the system of binary gender. Heteronormativity means, quite simply, that heterosexuality is the norm, in culture, in society, in politics. It means that everyone and everything is judged from the perspective of straight” (Samuel Chambers, “Telepistemology of the Closet; Or, the Queer Politics of Six Feet Under,” Journal of American Culture, 26.1.2003). might motivate a theoretical reflection on the obligations of art criticism and history in this new millennium with its old prejudices and oppressions.

Contemporary art and art criticism – as ever – spearhead cultural explorations. The range of images of sexuality and gender projected by contemporary art might function as an opening into the hidden erotic history of Polish subjectivity.

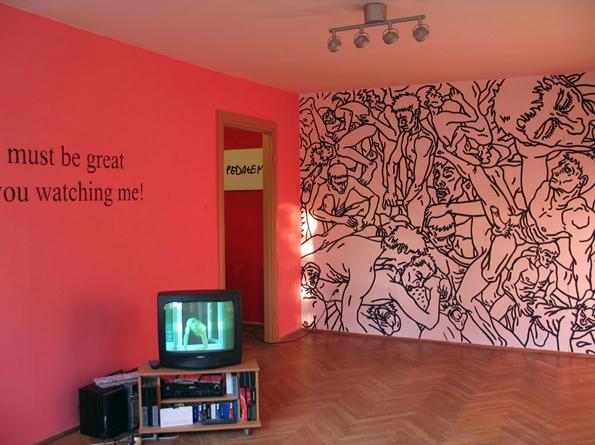

In 2004, I was invited by Izabella Gustowska, the artist and director of Poznan Art Fair 2005, to curate an exhibition which would be part of this annual event that celebrates contemporary art in Poland. I decided to mount an exhibition called Love and Democracy about the contested sexual landscape of this very moment. The first part of the exhibition took place in May 2005 as a part of Poznan Art Fair in the Kulczyk Foundation Galleries,Pawel Leszkowicz, Love and Democracy, in: Art Fair Poznan 2005, exhibition catalogue, The Fine Art Academy, Poznan 2005. the second, larger, part of the exhibition will take place in the Center of Contemporary Art “Laznia” in Gdansk in June 2006.

I faced a question: how do I prepare an erotic art exhibition which constitutes a response to the needs and conflicts of our times? How do you combine sexuality with love and public significance and how do you illustrate the relationship between public and private spheres? How do you find a third path for sexuality between pornography and the terror of Polish ‘sexophobic’ taboo and institutionalised homophobia? How do you convey the association of sex with the emotions and the intellect? How do you create an art exhibition which is simultaneously exciting, educational, and existential and gets to the core of what it means to love and desire a human being?

How do you create a Polish art exhibition which is unlike any previous exhibition,In 2000, in CSW Laznia Aneta Szylak organised an important international exhibition called All You Need Is Love which was still situated in the dominating hetero-normative model. See the All You Need Is Love exhibition catalogue, CSW Laznia, Gdansk 2000. and how do you open a new chapter in the presentation and conception of love and erotica? The simple answer is that there are many stories of love and sexuality, not one story, not only the heterosexual story. Writing, creating and showing the plurality of those stories is a humanist obligation and pleasure. Let me begin with the narrative which comprised the exhibition.

Love And Democracy – The New Millenium

The whole history of culture reveals numerous stories of gender, sexuality and love.This relates to the history and psychology of love expressed in the plural in the philosophy of Julia Kristeva. My curatorial concept of the exhibition was deepened due to Julia Kristeva’s book Tales of Love. Julia Kristeva, Tales of Love, translated by Leon S.Roudiez, Columbia University Press, New York, 1987. The French original Histories d’amour was published in1983. Through the works of contemporary artists, the Love and Democracy exhibition discovers a heritage which has been forgotten or forbidden in Polish culture. The images were chosen to inspire the work of memory and to function as open gate to the past which waits to be rescued from oblivion.

There are many types of art and many types of love, and a democracy should provide room for all of them. Artistic work is one of the best means of expressing the multitude of visual and love-related relationships, ideas, and experiences. Art is the key with which we can open a diversified plane of love, eroticism and aesthetics, beyond repression and discrimination. If we accept the pluralism of a democratic culture as a starting point, it is worth considering the issue of our right to enjoy the freedom of expression and love as one of the fundamental human rights.

The art presented in the exhibition revealed life in a variety of gender-related and sexual identity combinations and dramas. It discloses the various meanings contained in woman-to-woman, man-to-man, and woman-to-man relations. The exhibition does not just make room for a single perspective of love as seen by the representatives of only one sexual orientation or gender. It shows multiple love stories, multiple sexual narratives, and various images of femininity and masculinity. The viewer was introduced to a specific erotic continuum instead of a single account. From the queer perspective, I understood the embrace of all-sexual imagination (straight, lesbian, gay, bisexual) or expressions which make the sexuality unfixed, escaping the heterosexist norms of defined identity.

Polish society is involved in an ongoing debate concerning the closed and open forms of expression, relationships, gender, and sexuality. The exhibition was an artistic voice in this debate based on the assumption that every type of love and sexuality is equally important, fascinating, and worthy of being presented and recognised. The artists presented their erotic tales from the position of love and gender-related individualism. These were far removed from cliché, and existed between sentimentality and brutality, between the bodily and the abstract, between intimacy and politics, and between fantasy and reality.

As a curator I chose artworks which reflect the complex variety of contemporary stories and dramas of sexuality in contemporary Polish art, which goes beyond the heteronormative construction of this society. My subjective selection was based on the premises that both art and sexuality are forms of existence, knowledge, and social intervention. I based my exhibition not only on the politics of plural identities but, foremost, on the politics of diversity which so far has almost not existed in Poland in relation to sexuality and love. I also rejected the concept of minorities’ cultural expression to erase the majority ideology which permeates Polish society.

I decided to title the exhibition Love and Democracy as an homage to the 1960s and the sexual revolution. Due to communism and then religious fundamentalism the sexual revolution and the civil right movement in the name of minority rights did not truly happen in Poland. The country received only a very superficial idea of the important social unrest and transformation that changed western societies, and was often denigrated by the local media. Only at the turn of twenty-first century important civil rights and sexual changes started to occur. My exhibition tries to register this development in the field of visual culture and to be part of the new Poland and a new revolution.

In 2005, at this very moment during the pompous celebration of the Solidarity anniversary which has become part of right-wing parties election propaganda, I propose a need for a Second Revolution which must happen in Poland. The first one in the 1980s, under the banner of Solidarity, was conducted in the name of the free nation and the collapse of communism. The group identity of Poles stands behind it and has nothing to do with real democracy.

This Second, more difficult Revolution, must happen in the name of freedom and the rights of the individuals and minorities, opposing the danger of new nationalistic totalitarianism of group identity. The title of my exhibition relates also to the peace movement of the 1960s and is an ironic comment on the current Polish rampant militarism and involvement in Iraq. In short it is an exhibition organised and sexually constructed against Poland and everything for which the state officially stands for, especially on “moral” grounds.

Love and Democracy was an exhibition which was intimate and public as well as erotic and political. The artists invited or discovered by me represent a diversity of gender – and sexuality-related consciousness, and this is well-reflected in their art. Viewers were given the opportunity to encounter the floating narratives of erotic and love-related images and to confront them with their own desires and repression.

The exhibition intentionally confronted the viewers with representations coming from their own and their opposite sexual orientations thus extending the range of human perception. Consequently, the presented psycho-sensual world was simultaneously familiar and alien. Facing the other, unconscious part of our identity may be pleasant and soothing, but it may also lead to problems manifested in embarrassment, shock, disgust, uncontrolled laughter and even aggression. This is a form of our consciousness’s defence against the side of our psyche and of our society, which we have denied.

In a hetero-normative society, gay and bisexual men and women are conditioned to live out and acceptheterosexual codes. But for heterosexual audiences, queer images are dangerously uncanny. Therefore, the experience of homo-erotic images and identities and their otherness is usually problematic. And it is at this point that these love narratives become public and the personal psychodramas can turn into political issues and cultural wars. This is the type of love and identity-related drama that we are currently faced with in Poland, a country filled with homophobia. That is why all the psychological and sexual configurations have become part of the debate concerning democratic justice and relation between the majority and the minority. The exhibition also touched on social issues which concern the type of relationships in which achieving a partnership status and protection of human rights is extremely difficult. The selection of the works of art aims at creating a unique and utopian space for partnerships of plural sexual narratives.

A Mosaic of Identities

The exhibition Love and Democracy tells stories of love and eroticism through representations which concern various intimate and public aspects related to the pluralism of sexuality. The whole project is a mosaic of photographs, films, slides, tunes and words which in an artistic way reflect the conflicts, phobias, fantasies, desires and pleasure related to a multi-sexual society which erupted in Poland in the 90s.

Due to society’s and official institutions prevailing homophobia the rights of gay and lesbian citizens are the subject of a continuous dispute which is gradually being transformed into aggressive attacks, manifested recently in bashing and the unconstitutional prohibition of Gay Parades.Tomek Kitlinski, Joe Lockard, Poland’s Transition from Communism to Fundamentalist Hetero-sex, bad.eserver.org/issues/2005/72/kitlinskileszkowiczlockard.html

A week after Poland joined the EU, on May 7, 2004 in Cracow far right militia of parliamentary party, The League of Polish Families, attacked a peaceful demonstration of gays, lesbian and their supporters with slurs, stones and caustic acid. Violence towards gay people, as well as the far right hate speech, is an often observed media and political phenomenon and the former war of the genders is being replaced by a new conflict of sexual orientations.

The role of democracy is to ensure peace and safety for all citizens in a multi-sexual society and to restrain aggression and discrimination. Unfortunately, taking into account the current ethical underdevelopment of Polish social policy concerning gay and lesbian human rights, the situation resembles a political or rather street-boxing ring. Hence the symbolic significance of Zuzanna Janin’s installation Ring/ILoveYouToo (2001) which consists of a type of ready made boxing ring fitted into the space of the exhibition as an object reflecting current violent sexual climate.The ring is part of an installation which also includes a video film showing the artist as she is boxing with Przemyslaw Saleta – famous Polish boxer. Thus the ring and the video projection has a strong feminist message as reflection on heterosexual couple dynamism. Due to the symbolic significance of the object I decided to show the ring on its own which gave the work additional dimension commenting on the conflicts related to sexual identities. Zuzanna Janin has already exhibited this work in various versions in the past and agreed to present only one part of it – the ring without the performance.

Fighting in a boxing ring is not only a metaphor for private relationships, intercourse, women-men conflict, but also reflects the conflict between the defenders and opponents of gay and lesbian rights, i.e. the struggle between the various narratives of sexual identity. The ring is accompanied by several of Zuzanna Janin’s artistic books showing photographs from Polish Equality Parades.

The issue of civil rights for non-heterosexual people and of combating discrimination is the subject of the Niech nas zobacza (Let Them See Us) (2003) series of photographs taken by Karolina Bregula as a public art project.

The portraits of real Polish gay and lesbian couples holding hands in the streets, were part of a social campaign organised by NGO Kampania Przeciw Homofobii (The Campaign against Homophobia). The project failed as a public campaign because of the opposition of city mayors and violent reactions of far right politicians and hooligans. In the spring of 2003, the few billboards which were allowed were regularly attacked and destroyed by the far right youth militia All Polish Youth, and only in the seclusion of galleries as a touring show or illustrations in newspapers could the exhibition/photographs enjoy great popularity and have its significant media and public impact for human rights.

The portraits of real Polish gay and lesbian couples holding hands in the streets, were part of a social campaign organised by NGO Kampania Przeciw Homofobii (The Campaign against Homophobia). The project failed as a public campaign because of the opposition of city mayors and violent reactions of far right politicians and hooligans. In the spring of 2003, the few billboards which were allowed were regularly attacked and destroyed by the far right youth militia All Polish Youth, and only in the seclusion of galleries as a touring show or illustrations in newspapers could the exhibition/photographs enjoy great popularity and have its significant media and public impact for human rights.

The contradictory media and social reaction to Niech nas zobacza was the subject of Tomek Kitlinski’s sound/linguistic installation Ciac (To Cut), 2003, which was played loudly, filling the space. Visitors to the gallery were flooded with contrasting homophobic and homophile statements taken from the Polish media and politics, read out loud by the actress Anna Swietlicka who emphasises the tragicomic and crude character of the whole debate with her hysterical vocalisation. The text was a linguistic collage of conflicting opinions on gay and lesbian rights, which exploded in Poland in the year 2003, around the discussions about joining the EU, the public art campaign Let Us be Seen, and the possibility of same-sex partnership. This maze of voices has brought the subject to a crisis of meaning and language. Public and private discussions have always been staged as divided into two opposing camps: for and against sexual minorities. This vicious and tragic dualism doesn’t allow any meaningful social and legal solution. There is no idea of consensus. A debate always framed in the context of contradictions makes counter-speech very difficult and produces hate-speech.

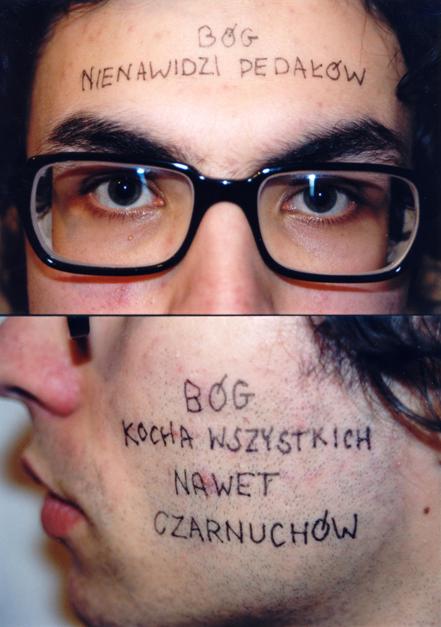

The painting of Piotr Nathan, who was born in Poland but lives in Germany, openly deals with sexual discrimination and hate speech. Piotr Nathan is an internationally recognized artist who often works with gay themes. The painting Pedaly do gazu (Faggots to Gas) 2005, which was ironically included in the exhibition Love and Democracy, consists of silkscreen photographs of the artist as a child with a hateful homophobic slogan written on it: “Faggots to Gas.” One can find such slurs painted on Polish walls or directed at gay people on the street. Significantly the sentence combines homophobia with anti-Semitism and indicates the current ethical crises of human rights consciousness and the inability of the homogenized Polish society to relate to internal otherness, both sexual and ethnic.

In Eastern Europe the trauma of Holocaust is still imprinted on the bodies of other contemporary “strangers.” This poignant juxtaposition of text and image turns the painting into a complex self-portrait with autobiographical traces relating to the artist queerness and Jewishness. Piotr Nathan who emigrated to Western Germany in the 1960s, emphasizes his alienation from Poland and his feeling of not belonging to this culture; the touching painting explains personal drama behind his critical distance, and diagnoses the hatreds imbedded in Polish society.

The painful messages of Tomek Kitlinski and Piotr Nathan art were balanced withmore idealistic vision of Rober Rumas, Katarzyna Korzeniecka and Anna Tyczynska and another series of Katarzyna Bregula. The tension of the exhibition was lessened with Robert Rumas’s Demosutra series of photographs (1994-2004). These show two hands connected in different gestures with the sky in the background. The unity and ascension into the heavens in the process of touching is almost an abstract concept if gender is not taken into account. The body is surrounded by the color blue in an almost cosmic connection; there seems to be a reference to Plato’s metaphysical concept of unity.

These images present pairs and solitude, prayer and tenderness, elation and retreat, closeness and confinement. The two hands and the sky as an image of togetherness of love and eroticism, as an image of reconciliation, as an utopian icon for Love and Democracy and “new Poland”. Moreover, the artist confronts us with the traditional symbolism of gestures which expands from religious iconography to sexual connotations. The holding of hands from Niech nas zobacza is transferred by Robert Rumas into a universal dimension which encompasses all types of relationships as well as sexual positions.

The next group of works in the exhibition moves from a social to an intimate dimension. A series of self-portraits Mezatki (Married Women, 2005) executed by Katarzyna Bregula with another women photographer, represent an emotional and bodily closeness of two young women artists living together. The poetic and aesthetic quality of this sophisticated and subtle compositions evoke the atmosphere of safe domestic haven, sensual comfort and lesbian eroticism.

The presentation of hetero-and homosexual relationships, without the marginalization of any of them, was the main idea of the exhibition and this was ideally envisioned in the portraits of various straight, gay and lesbian couples photographed by Katarzyna Korzeniecka. The viewer is invited into different bedrooms in which the couples in love are photographed. Their names are given in the titles of the works: Dominique and Piotr, Magda and Tomoho, Magda and Rafal, Szymon and Kasia, Krzysztof and Suppie, Leon and Suppie and Rachel and Sylwia (2000-2004).

In the life-size images, photographs transferred on a white bed sheet, we see men and women immersed in sensual ecstasy, caresses and tenderness or simply holding each other. The white bed sheets imbue the photographed nudity of the bodies with intimacy, softness and sentimentality. The strongly emotional character of the photographs makes their eroticism intense, albeit idealistic and pure. Katarzyna Korzeniecka’s images of individuality and sexuality come from a world of unrestricted eroticism and fulfilment, which is not accompanied by feelings of guilt, shame, or sinfulness, and these photographs are, therefore, almost therapeutic in their character.

As a contrast, the fascinating and perverse tradition related to prudery is referred to in the compositions and sculptures made of embroidered bed sheets by Anna Tyczynska. The series is called Kocha, lubi, szanuje (Loves, Likes, Respects, 2004). The holes in the square fragments of bed sheets are surrounded by embroidered patterns of floral and symbolic motifs. On the one hand, the decorated openings in the fabric can evoke vaginal forms, and on the other, they relate to Victorian bedding and nightdresses with openings for the genitals, recommended for married couples to make love in. The artist presents a series of ten intimate embroideries of this kind. Their subtlety does not exclude a hint of perversity. The art of Anna Tyczynska shows sensuality in a more abstract way than the other works in the exhibition. The folds, openings and ornaments of the fabrics imply the mysteries of erotic matter in a very decorative and sensual way.

Hanna Nowicka’s photography series Insignia (2000) affects the viewer with a more direct and teasing eroticism and play with dominant and passive gender positions observed from a feminist perspective. The relationship between male and female subjection and domination as well as the states of being active and passive are presented by the contrasting of fragments of the male and female body and their fetishist attributes. The photographs are composed in such a way that they look as if they were made from the male’s eye perspective. The imperceptible ‘him’ looks down at his partner’s passive feminine body and sees it from the angle of his penis, which is clearly visible in the photograph and which demarcates its composition axis. The artist arranges desire from a heterosexual and phallic point of view.

It is, nevertheless, clear that it is she (the women-artist) who has created the image, whilst the male in his genital nudity remains one of the passive objects of her observation with the compositions concentrating the view on his penis. The photographs make the viewers strongly feel their gender and sexuality and also recognise their own erotic perspective. Additionally, in order to stress the visceral character of this visual and sexual charade of glances, genders, bodies and desires, a stain of blood appears between the male and female figures. It is a quite disturbing phenomenon that this suggestion of violence makes these photographs more exciting and repulsively attractive. Images like these seem to stem from the dark side of desire and are quite distant from the idealisation of love.

Whilst Katarzyna Korzeniecka presents joy and fulfilment in a relationship on partnership terms, Hanna Nowicka depicts the deeper and concealed price that one has to pay for love and the imbalance of power. In their work both artists expose two individual philosophies of love accompanied by a multi-sexual perspective. In the photographic composition For Hockney (1997) Hanna Nowicka looks at a pair of naked men at the seashore in a homoerotic way, suggesting this approach to the viewer.

Bogna Burska is another women-artist who explores the theme of violence in male-female relationships in her video film Deszcz w Paryzu (Rain in Paris). The found footage video installation comprises fragments of cult erotic movies which are set in Paris.Bogna Burska quotes films such as: Queen Margot, Marquise, Dangerous Liaisons, Frantic, Henry and June, Quills, Lovers on the Bridge and Night Wind. The compilation made by the artist depicts the divas of French cinema, for example: Isabelle Adjani, Sophie Marceau and Catherine Deneuve. (Who would not want to be one of these women and who would not want to be with these women?) The artist chose scenes which depict a violent confrontation between a man and woman with blood in the background. The subsequently presented erotic scenes concentrate on the female figures found in states of romantic or sensual insanity, subjection and despair.

Deszcz w Paryzu is a review of women’s submission to love and sensuality as well as French existential eroticism which is known for its subversive edge, and since the 1950s, has had a strong influence on Polish culture. Apparently it is only the French who know how to depict, talk, write and think about sexuality, and this is best done in Paris settings. Female beauty fires the French imagery of pleasure and transgression and this, to a great extent, is based on female masochism and submission. Nevertheless, this imagery carries such a charge of poetry and existentialism that it is impossible to resist itserotic aesthetics, particularly in relation to Polish culture, which lacks the intensity of such features.

There is No One Masculinity!

Masculinity, as a gender norm, is especially closed and codified, causing exclusion or stigmatization of all individuals who cannot or do not want to conform. This is why opening masculinity, introducing pluralism to it, questioning heterosexual domination, and feminizing it, has deep existential, political, and liberating potential. The revolution is in discovering, writing, imagining, visualizing, and performing multiple forms of masculinity, numerous stories and male identities. The new masculinity begins with liberation via freedom of sexual orientation and noncontrastive relations to womanhood. Homosexual and bisexual male identity, as well as nonhomophobic heterosexual masculinity, play an important role in constructing new nonhierarchical, democratic, and humanistic masculinity, which may eventually match the contemporary liberated femininity.

Thus another group of works in the exhibition Love and Democracy presented various views of male sexuality and the male body. Equality means a consistently honest approach to both female and male nudity beyond the traditional domination of the female nude in Polish art and the taboo surrounding the full male nude. And this is why the exhibition aims at exposing the sexuality of both genders in a democratic way. What is more, the artworks present critical approach towards traditional masculinity and project vision of post-patriarchal masculinity. The discovery or just imagining of post-patriarchal masculinity play a psychoanalytic and strongly political role in a culture where official media and political rhetoric is based on fundamentalist, archaic, and homophobic models of manhood and boyhood.

Katarzyna Korzeniecka, Hanna Nowicka, Anna Tyczynska and Bogna Burska look at love and eroticism from the perspective of female desires and concentrate on female metaphors, fascinations, and perversities, whereas issues related to multidimensional masculinity are reflected in the works of Tomek Kozak, Dorota Nieznalska, Eliza Ciborowska, Karolina Wysocka, Pawel Kruk, Karol Radziszewski and Wojciech Gilewicz.

Just as Bogna Burska looks at film scenes from a female point of view, Tomek Kozak is equally interested in male passions and erotic traps represented this time in Polish cult movies. In his found-footage video installation Plec i charakter (Gender and Character) 2004,The title is a reference to the famous philosophical and sexology treaty written by Otto Weininger in 1903. the artist used Krzysztof Kieslowski’s famous A Short Film about Love to make his own abridged version of this movie, a type of video clip accompanied by the song Nic nie moze przeciez wiecznie trwac (Nothing Can Last for Ever) performed by the tragically deceased Polish pop singer from the communist period, Anna Jantar. Kozak’s pop video is a captivating explosion of sounds and images which bring us closer to the core of a teenager’s love and desire, and the power which a woman holds over him.

Due to the combination of cartoon elements with the actual film scenes, in contrast with the original by Kieslowski, the viewer does not look at a deep and gloomy personal psychodrama, but at an energising visual stream which intensively pulsates in the imagination long after the video is over. This is a work that cannot be easily forgotten and which the viewer wants to see and hear repeatedly due to the strong audio-visual pleasure. By reaching for various sources in an eclectic way, particularly national classics like the works of Kieslowski and Jantar, the artist amuses the viewer and triggers reflection of Polish myths concerning love. His art is also a critical but entertaining form of nationalistic memory preserved in visual cliché.

Pawel Kruk photographs and videos from the extended visionary series Messiah College (2003-2005) are semi-self-portrait studies of various psychosomatic and religious stages of masculine beauty, ecstasy, suffering and rapture. Messiah College is also a complex catalogue of the history of the male nude with multiple exposures of the male body and its sensations. The artist tells the cultural stories of the male body and its iconography. In the context of the exhibition the erotic-narcissistic-mysterious character of the images is crucial. Narcissism as a foundation of a person’s identity is one of the basic elements of Western erotic language. The exaltation and affirmation of masculinity presented by Pawel Kruk, might provoke a critical reflection on masculinity and its obsessions and function for religion and the contemporary body cult. And that is why the art of Dorota Nieznalska, the champion of dark portraits of masculinity, is the perfect partner for his Messiah’s cycle.

I chose three large colour photographic prints from a recent Nieznalska’s series Implantacja perwersji (Implantation of Perversity, 2004) to be shown in the exhibition as an S&M triptych. Two of them are allegorical: Wiernosc PL (Fidelity PL), a monumental image of a depersonalised male torso and back with a type of “whip-leash-spiked collar” on the neck, while the head is not visible. The last of the three images is Kaganiec meski (Male Muzzle), a photograph of a special black leather muzzle for the penis on a red background. The criticism of male power and domination, which is typical of the artist, is combined with a sexual approach to fundamental nationalistic masculinity that has targeted Dorota Nieznalska with the violence of censorship for her outstanding installation Passion. Another striking feature is the erotic character of the analyses of the male sexual drive. The photographs are sado-masochistic and fetishist and can equally provoke reflections about desire as well as desire itself.

I believe that creating a new, diversified, and just space for love and sexuality is only possible after the breaking through the traditional heteronormative gender roles, including the patriarchal masculinity which is the subject of Dorota Nieznalska’s visual studies. In this context let us look at some alternative images of liberated masculinity. The joyous and unrestrained vision of the male body presented in Eliza Ciborowska’s photographs Lubiezne, Woda i Wojti (Lascivious, Water, and Wojti) (2003) transcends the trauma of hetero-normative imprisonment and gloom of Polish masculinity.

Three young, well-built naked Polish lads are playing with one another as they pose for the photographs in natural surroundings. They touch one another and their bodies are arranged to form various compositions, all in the frivolous and happy atmosphere of a paradisiacal garden in the Polish countryside. They are free and rollicking in their homo-erotic triangle which glows with natural health and humour. They are aware of their sexuality and are happy to display it. As with Korzeniecka, Ciborowska views male sensuality without any taboos and with great aesthetic taste and historical references to homoerotic male nude in the history of photography. Her art is an idyllic erotic fantasy in which the actors participate for their own as well as the viewer’s amusement. The sensual humour liberates and opens the straight masculine gender performance.

An open celebration of gay erotic iconography is manifested in Karol Radziszewski’s photographic portraits and self-portraits.

His 2005 exhibition brutally entitled Faggots declared the artist homosexuality and his identity based art which consists of the male nude, scenes of gay sex, pornographic drawing and frescos. His images, in a very explicit way, treat the gay subject as the artist’s individual brand/mark on the prudish scene of contemporary Polish art. The artist publishes also a gay artzine DIK. Radziszewski’s position signifies the beginning of out-of-the-closet phase in Polish culture.

His 2005 exhibition brutally entitled Faggots declared the artist homosexuality and his identity based art which consists of the male nude, scenes of gay sex, pornographic drawing and frescos. His images, in a very explicit way, treat the gay subject as the artist’s individual brand/mark on the prudish scene of contemporary Polish art. The artist publishes also a gay artzine DIK. Radziszewski’s position signifies the beginning of out-of-the-closet phase in Polish culture.

Another gay artist, Wojciech Gilewicz, in a series of his double self-portraits Oni (Them) photographs an imaginary dialogue or affair/romance with himself. We see two young men played by the artists in an enigmatic, intimate or erotic relation. The meaning of those images oscillates between self-love or narcissism and an allegory of radical loneliness and despair.

Another gay artist, Wojciech Gilewicz, in a series of his double self-portraits Oni (Them) photographs an imaginary dialogue or affair/romance with himself. We see two young men played by the artists in an enigmatic, intimate or erotic relation. The meaning of those images oscillates between self-love or narcissism and an allegory of radical loneliness and despair.

I would like to emphasize the importance of photography and of the traditional genre of the self-portrait for contemporary young Polish male artists who want to place themselves in an alternative to heterosexuality narration or to manifest or encode their homosexuality. The self-portraits enable them to open the male identity for other sexual possibilities and escape the narrow gender imprisonment prepared for them by Polish culture. Nowhere is this more evident then in drag self-portraits by Maciej Osika.

The sensual self-portraits of Maciej Osika (2002/2004), which make use of a technique which combines analogue and digital photography, depict the artist in stunning female incarnations inspired by the history of art, cinematography, and high fashion. Here gender is a performance and a visual construction, not a biological role. The photographs are linked by elements like self-portraits, narcissism and phantasmatic identification with the opposite gender. By feminising the image of his masculine identity the artist liberates himself from its restrictions in the quest for a freedom of gender-related fantasies and roles. His self-portraits are as auto-erotic as the male nude of Pawel Kruk, although they achieve this effect on a completely different level by identifying with one’s inner and cultural femininity. To make these self-portraits, the author needs to engage in the enjoyable process of dressing and making up as well as masking of himself. Like the idyllic homoeroticism presented by Eliza Ciborowska these works are an important representation of the world of erotic fantasies and alternative masculine performances.

The sensual self-portraits of Maciej Osika (2002/2004), which make use of a technique which combines analogue and digital photography, depict the artist in stunning female incarnations inspired by the history of art, cinematography, and high fashion. Here gender is a performance and a visual construction, not a biological role. The photographs are linked by elements like self-portraits, narcissism and phantasmatic identification with the opposite gender. By feminising the image of his masculine identity the artist liberates himself from its restrictions in the quest for a freedom of gender-related fantasies and roles. His self-portraits are as auto-erotic as the male nude of Pawel Kruk, although they achieve this effect on a completely different level by identifying with one’s inner and cultural femininity. To make these self-portraits, the author needs to engage in the enjoyable process of dressing and making up as well as masking of himself. Like the idyllic homoeroticism presented by Eliza Ciborowska these works are an important representation of the world of erotic fantasies and alternative masculine performances.

An authentic transformation of gender and duality is presented in the well-known series of three “transsexual” photographs by Alicja Zebrowska Kiedy inny staje sie swoim (When the Other Becomes Familiar, 2001). The baroque-style portraits of a naked transsexual (male to female) person who resides in luxurious purple fabric inside a large mirror chamber introduces the element of the lavishness of the gender ambiguity, which surpasses the limitations of the body, the destiny of nature. We are on the other side of the looking glass, beyond the ring of the masculine-feminine struggle, in a world of primeval, androgenic, and sensual plenitude. This, however, is not a fantasy, but a real existential experience, presented by the artist as splendour of freedom and transformation. The beauty of the in-between state of being disrupts the safe but destructive conventions of traditional gender dualism which is the basis of heteronormative society.

One of the features of a democratic public sphere of the city live is the pluralisation of the clubbing scene, i.e. the existence of clubs frequented by the representatives of various sexual orientations and social groups. Since the early 1990’s gay clubs in Poland with their ecstatic discotheques have been enjoying increasing popularity.

In fact the appearance of gay clubs after 1989 was one of the symptoms of democratisation of the public space and of commerce. Since Western metrosexuality is not really a popular performance among straight men in this country whose look is still very conformist and homogenised, a new post-communist masculinity could have been noticed manly in gay clubs. This is where one can meet a completely new type of fashion-conscious young Poles who are looking for perhaps short-lived pleasures and a retreat from the surrounding grey reality.

The important urban scene marginalized by the media found its reflection in contemporary art. Katarzyna Górna’s Barbie Bar (2004) is a video installation that shows ritual dance and costumes of boys in a gay club, which the artist has depicted as hallucinogenic. The club atmosphere leads us to club art and the lesbian environment. This is art which decorates a secretive lesbian clubs in Lodz. The comic strip (cartoon) Darkless (2004) by Justyna Apolinarzak records the everyday life of girls who love girls: their family lives, parties, relationships and language as well as their fashion, problems and conversations.

All this is presented in a familiar format of cartoon which enables the viewer to directly see a completely unknown Polish youth environment. This is a work of art which is fun and easy to perceive, whilst at the same time it is a unique anthropological document that strikes us with its fresh and direct approach. This is the first significant image of lesbian subculture and “girlhood” in Poland. In the milieu still not discovered and underrepresented, art – as always – opens the social frontiers of seeing.

From public campaigns to intimate portraits, from a theatre of sexuality to club subcultures, the exhibition shows the stories of love and identities in a period of floating sexuality which disrupts from inside the Polish heteromatrix, sexophobia, and censorship, and democratise society and culture. One may note in the artworks many references to the visual vocabulary and figuration of popular culture (film, advertisement, soft-core erotic, illustration). This form of pop art combined with the reflection on private life and the everyday is a characteristic feature of the young Polish art at the dawn of the twenty-first century. The political dimension of art here is less obvious than in the critical art of the 1990s, yet the cultural policy of sexual diversity which stands behind my curatorial collection has a clear political and educational message of sexual equality and transformation of the homophobic social regime. This sexual politics of the Polish intimate version of pop art is a reference to the western pop art of the 1960s as an art movement of the era of sexual revolution.

What Kind of Democracy Do We Want?

Democracy, love, and art are all concepts with Greek origins, a long history, and problematic modern and postmodern incarnations. Their value is continuously analysed and questioned. Love and democracy in particular are flexible and important phenomena and this is why it is so important and pleasing to focus on them. Love and democracy (as concepts and experience) connect us with a society and move us out of alienation and egocentrism. Thinking about them and representing them touches upon the most fascinating values of humanism.

On the one hand it is assumed that democracy is the power of the majority, and on the other it is believed that the rights of minorities have to be respected since all citizens are equal and free. The exhibition has been inspired by a liberal and humanistic tradition which focuses on individuality in its multitude of forms and on the politics of diversity. Democracy in relation to sexuality and art does not only mean the freedom and equality of the numerous forms of love, but also the freedom and equality of the images of love and identity. By grouping the expressions of various love-related orientations and the problems they face I intentionally expanded the dominating reductive heterosexual model. The classic scholars of democratic thought like Alexis de Tocqueville,Alexis de Tocqueville, Democracy in America, ed. J.P. Mayer, M. Lerner, transl. G. Lawrance, New York 1966. John Stuart MillJ.S. Mill’s famous essay On Liberty (1859) is directed against “the tyranny of the majority”. and, presently, Claude LefortClaude Lefort, Essais sur le politique, Editions du Seuil, Paris 1986. and Martha Nussbaum,Nussbaum Martha C., Cultivating Humanity. A Classical Defense of Reform in Liberal Education, Harvard University Press, London, Cambridge 1997. declare that the tyranny of the majority threatens democracy and that it is necessary to care for others. The whole concept of the exhibition is determined by this idealistic vision.

This understanding of democracy relates to all social and psychological levels, including sexuality and love which should not be regarded separately. The power of love can be used to enhance and personalise the concept of democracy, and democracy can be used to tell numerous stories of love and subjectivity which enrich new humanism.

Towards A Democratic Public Space – The 90s

In the second part of my text I would like to sketch the short history of queer (non-heteronormative) presence in art in the first decade of Polish democracy. Moreover I want to suggest that the question of human rights for gay and lesbian citizens, the radical other in homogenous Poland, including rights for representations and expression in the cultural arena, functions as lens through which I view the condition of democracy and diversity in society and culture alike and the condition of the humanist values of tolerance and respect for human freedom and independence. In my vision of art, public space and, democracy, I draw on the concept of the democratic public space and citizenship which was outlined in the political philosophy of Claude Lefort, and in Rosalyn Deutsche’sRosalind Deutsche, Evictions. Art and Spatial Politics, The MIT Press, 1996. thoughts on public art.

I would like to pose the question of a possibility for visual culture to operate as a vehicle of alteration in culture and mediation of otherness in relation to sexual and amorous differences in a society where gays and lesbians are politically staged as an underclass. Moreover, in a country which still hinges between democracy and fundamentalism, the fragile anddifficult problem of sexual difference, offers for culture the margin for subversive edge and revolutionary force.

It is precisely the transforming energy which, in Eastern Europe, is still contained in the sexual otherness that makes the subject here so different from its Western incarnation. The commercial commodification has not happened yet and the political and social implications are revolutionary. Hence my idea: in Eastern European traditional societies and quasi–democracies, the new kind of dissidence is sexual and love dissidence, and the Polish case gives the best example. Therefore the Polish case of homosexuality and visuality may open a broader reflection on the role of the difference and local context in the studies and expression of sexuality.

My text has an introductory character, opening a vista for further research in Polish art history and visual culture alike. As a method of interpretation I have chosen contextualised iconography in my search for homosexual motifs in the art of the 90s. That is, the historical period after the political break, collapse of communism (1989), and during the democratic and capitalist transformation. Behind the iconography lies a certain political approach connected with the concept of the democratic public and institutional space.

Therefore, in my analysis the homosexual iconography functions as a form of social iconography too, due to the social implications of the subject. As a point of departure I take the necessity of pluralism in democratic visual culture: a pluralism which embraces the right for expression, also about sexuality and its diversity. The idea taken for granted, even commodified in the West, still has a potentially subversive and highly political edge in post-Soviet Central and Eastern Europe which under the influence of the European Union only began to embrace the concept of human rights for all.

Art which deals with female and male homosexuality is located in a fragile area between the public and the private, between subjectivity and ideology, and finally between forces of freedom and repression. Thus such forms of artistic expression may function as a symptom of the quality of democracy in a culture emerging from transition and entering the capitalist market and the culture of human rights. This part of the text concentrates on such a time of change, yet before the market has tempered the subversive and significant feature of the problem through commercialization.

I divided my story into three sections entitled In the Town Hall, In the Body, and In Femininity, to explore different levels of the issue.

In the Town Hall

In 1992, the office of the Director of the Provincial Centre Of Culture, located in the Town Hall in Gdansk, was magically transformed for three days by covering the interior and the historic furniture with snow-white mist of vegetal down. The action and installation of a young artist Krzysztof Malec was entitled Silence; it altered the official, institutional space and exposed to the public a alternative version of the office.Danuta Cwirko-Godycka, Krzysztof Malec – In the Field of Nature, in Mystical Perseveration and a Rose, exhibition catalogue, State Gallery of Art, Sopot, 1992, p.65.

The furniture, floor and window-sills were covered with a layer of down which subtly and radically transformed the space, dematerialised it, changing the reality of things into a ghostly and shadowy presence. The filling of the room with a weightless down – the seeds of a marsh plant – effaced material shapes and sharp edges and created theatmosphere of secrecy and otherness.

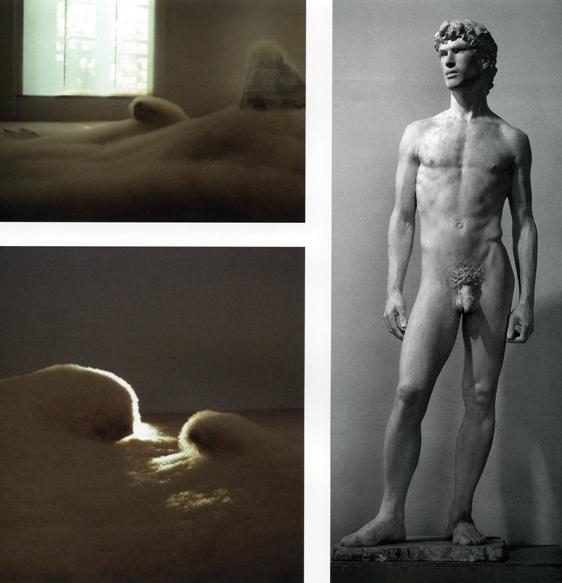

This poetic installation evokes many associations which I don’t want to reduce, but it is the title Silence which remains for me particularly significant: unspoken presence in the institutional architecture, silenced yet all-covering, altering reality yet beyond language. However, taking the next step, the artist found his own, much more direct expression and material, bodily presence in a sculpture The Male Nude in the exhibition I and AIDS.

In 1995, three artists (Grzegorz Kowalski, Katarzyna Kozyra and Artur Zmijewski) organized in Warsaw,in the “Capital” cinema, an exhibition I and AIDS. It was the first art show devoted to AIDS opened in Poland, while in the West art accompanied the epidemic from the beginning in the early 80s. The exhibition which related to sexuality was closed after two days. The manager of the cinema regarded it as too controversial and the problem of AIDS was considered “improper” for the youth. As the title captured it, the exhibition presented subjective view of the artists faced with sexuality in the time of AIDS. Images of fear and anxieties prevailed. The works were dominated by sex and the body seen in the context of threat and surveillance. In the centre of the show stood proudly a white and muscular plaster sculpture, The Male Nude by Krzysztof Malec from 1994 (made two years after Silence). This time the artist turned to the real matter – desire crystallised, fully embodied, erotic but deadly, crowning the exhibition I and AIDS.

In 1995, three artists (Grzegorz Kowalski, Katarzyna Kozyra and Artur Zmijewski) organized in Warsaw,in the “Capital” cinema, an exhibition I and AIDS. It was the first art show devoted to AIDS opened in Poland, while in the West art accompanied the epidemic from the beginning in the early 80s. The exhibition which related to sexuality was closed after two days. The manager of the cinema regarded it as too controversial and the problem of AIDS was considered “improper” for the youth. As the title captured it, the exhibition presented subjective view of the artists faced with sexuality in the time of AIDS. Images of fear and anxieties prevailed. The works were dominated by sex and the body seen in the context of threat and surveillance. In the centre of the show stood proudly a white and muscular plaster sculpture, The Male Nude by Krzysztof Malec from 1994 (made two years after Silence). This time the artist turned to the real matter – desire crystallised, fully embodied, erotic but deadly, crowning the exhibition I and AIDS.

Classical, The Male Nude clearly referred to Michelangelo’s David, an emblem of homosexual code in art. The ancient and Renaissance male nude, so rare in Polish art in its entire history, appeared this time in a tragic context of exhibition devoted to AIDS. Critics pointed out that the sculpture embodied a remarkably beautiful man’s flesh which exudes sexuality to the level of social provocation. The curator of the exhibition Artur Zmijewski wrote that the sculpture is a “monstrance of the male body” and the sculpture of genitals borders on mimetic extremity.Artur Zmijewski, “Und morgen die ganze Welt…. About the exhibition Me and AIDS“, Magazyn Sztuki (10 / 1996), p.262. The vegetal down in the artistic intervention in the government office in Gdansk, where meanings were open for all kinds of projections, was replaced by an obviously erotic figure shown in the frame of an exhibition, which stereotypically linked AIDS with the issue of homosexuality.

The homoerotic directness of Krzysztofa Malec’s plaster sculpture drew my attention to his earlier metaphorical action with down and inspired a look at the installation Silence from an-Other, queer perspective.

It seems to me that the transition from Silence (1992) to Male Nude (1994) marks the dialectic of homosexual presence in Polish society and culture in the 1990s: a paradoxical circulation between official invisibility and visual fetishism and a move from implicit/coded and explicit presence. What does it mean?

It is the title Silence which reflects one side of the presence of the question of gay and lesbian identity and rights in contemporary Polish life: the sphere of politics and institutional legislature in Poland. In the language of power and law the subject was hardly visible or it was treated with disdain or even contempt. But the media told another story; they were more “hospitable.” The sexual otherness is an attractive product to sell, in a limited dose, of course, especially in a form of talk-show trauma, comedy or an erotic tease. There are Western films and programs on the subject broadcast occasionally on commercial TV channels late at night. However they function as a form of entertainment, not of education and are hardly ever discussed in the context of democratic society and its ethics.

But the Polish gay and lesbian associations (such as Lambda, Campaign Against Homophobia) are working mostly on legal changes, on the improvement at the level of institutional, official policies of the state towards non-heterosexual citizens. At stake are such key issues as: establishing a constitutional law against discrimination, introduction of partnership agreement for same-sex couples, regulating inheritance and taxes, starting of anti-homophobic education at schools. However, in the 90s one could observe a lack of official reaction to these postulates, in spite of simultaneous sporadic commercial exploitation and ephemeral discussion. Hence the down of silence filled the office of the director of the Provincial Centre of Culture, located in the Town Hall of Gdansk, in a public institution associated with power much more directly than any gallery of art. In this way Krzysztof Malec’s installation Silence was a closeted intervention of sneaking in a space shut down for homosexual rights, a space where expression and hearing still seems impossible. Evidence of this negation is most clear in the Polish Constitution of 1997.

First, let us note that in Polish law homosexuality was decriminalized in 1932, very early in comparison to the processes of depenalization in Western European democracies in the 60s and 70s. Formally the surprisingly liberal law also functioned in the communist Poland but it did not change at all the negative attitude of the society and the authorities. In general, under communism, homosexuality existed as a social taboo or social pathology, registered mainly in medical and criminal context. The outcome of this prudish and pathological attitude still exists and works in the social field of today, and the recent Constitution is a continuation of it. Even despite the liberal legal tradition, prejudice rules.

The Constitution of April 2, 1997 lays out in Article 32 the fundamental principles of non-discrimination: the principle of equality before the law, the principle of equal treatment by public authorities, and the prohibition of discrimination in political, social or economic life on any grounds. The existing Article 32 is a result of a compromise reached in the debate preceding the adoption of the Constitution. One of the drafts of Article 32 included sexual orientation as one of the criteria of non-discrimination. However, the draft was rejected in favour of a provision on non-discrimination “on any grounds.”

In the light of generally accepted interpretation, this existing provision also implies non-discrimination on grounds of sexual orientation. However, the fact that the explicit clause on non-discrimination on grounds of sexual orientation in the draft caused the rejection of the draft – suggests that there is a strong trend to challenge the principle of equality of homosexual people before the law in Poland. It is worth adding that the draft which included the sexual orientation was strongly opposed and criticized by the Catholic Church, the right wing politicians and president Lech Walesa and other Solidarity politicians who stated that the inclusion could be a danger to the family and the moral upbringing of children.Jerzy Slawomir Mac, ”Prawo do rownosci,” Polityka (15 / 2001), p.22.

In spite of the general non-discriminatory provision, the Constitution also includes specific clauses extending protection tosocial groups considered most vulnerable to discrimination or violation of rights. Unfortunately, the groups which merit special protection do not include sexual minorities, even though they are obviously vulnerable to discrimination. The only positive aspect is that after joining EU in 2001 the Polish government was forced to implement protection against discrimination based on sexual orientation in employment and housing.

But the embracing and emphasizing of sexual orientation in the general constitutional principle of non-discrimination seems to be a fundamental step in the constitution of a democratic state protecting its citizens, especially in the situation of gays and lesbians in Poland. Let us not forget that one deals here with a small minority towards which, as polls show, most Poles (70%) still declare dislike and even contempt, and powerful far right parties like the League of Polish Families and Law and Justice declare open hostility. Thus the progress of acceptance and tolerance is slow and anti-homophobic education is hardly present in the media and at schools.

Very often the statistics cover violence and injustice existing in social life. Let us look at a second Town Hall acting in the story. Words and Gestures of the Town Hall Tower – the action of Polish internationally recognised artist Krzysztof Wodiczko was organised in Krakow’s Market Square in August 1996. His public projection for a while broke the silence when, through art, the tower of Town Hall spoke with the voice of a young gay man. While in the action of Krzysztof Malec, the office of Town Hall in Gdansk was filled with the mist of silence, four years later in 1996, the wall of Town Hall in Krakow uttered a voice of pain and despair.

Krzysztof Wodiczko is a champion of critical public art: he uses a technique of public projection on the walls of architecture associated with power. The artist projects images of exclusion, brutality, and injustice provoked or legitimised by the power. In his art, Wodiczko continues a study of otherness and alienation, which he calls xenology, from a Greek word xenos. The Krakow action was a piercing research of xenology, painfully diagnosing the condition of human rights in democratic Poland and its failure of social hospitality.

It was a dark rainy evening. The artist projected images of hands holding various objects, as if attributes of human fate, on the brick wall of the Town Hall Tower in the centre of the Market Square. Formerly, the Tower functioned as a municipal prison with dungeons and the space around the Tower was used for public executions. It is a telling site for Wodiczko’s projection. The images of hands were accompanied by voices resonating across the square. One of the voices told the story of an abused wife, another spoke about the life of a drug-addict: about fear of death and longing for a family. A third voice spoke about the fate of an elderly blind man: his rejection by the son and about being lost in the unseen space of the city. Another image represented gesticulating hands. The voice that went with them told the story of a young gay man, the physical pain of having been beaten and the spiritual pain of rejection.Jaroslaw Lubiak, “What Tower Would Like to Say?”, Exit. New Art in Poland (October –December 1996), p. 34.

The hands of the abused wife, of the alcoholic, of the blind man, of the drug-addict, of the gay man are emblems of the excluded and the silenced social subjects. The artist decided to let the ostracized speak in a public space that is in society: in a place where society does not allow the excluded to speak, removing them from its awareness, pushing them to the edge of non-existence, closing them in a circle of exclusion where they find loneliness, fear and pain. In Wodiczko’s view, a public projection can change the life of the marginalized and humanize the violence of public and private space. For a moment, the Others can be present in the center of social recognition; they can express themselves in the most sublimated language of art.

Regrettably, xenology meets with victimology in Wodiczko’s art. The other is at the same time the oppressed, the victim. Alienation, violence, intolerance, indifference overlap with the experience of otherness and marginalization in the society. Looking from the perspective of emigration, Krzysztof Wodiczko – a Pole and a foreigner alike, free from local prejudices and taboo – reached to the core of isolation and exclusion experienced by stigmatized and ostracized individual.

Words and Gestures of the Town Hall Tower depicts Polish society without mercy and forgiveness. It is art about not even a failure but denial of hospitality and humanism. It is art which becomes the space of hospitality and of education. By means of his projection, Wodiczko lightens darkness and lifts the veil of oblivion. The tower invaded by the image and voices of the “rejected” becomes a sort of monument to them and anti-monument of the unjust society to which they belong.

This painful projection of Krzysztof Wodiczko dealt with the tragic destiny of the individual in the relation to the society and history – at this particular moment. The artist allowed the oppressed and the forgotten to emerge in the public sphere and through the artistic intervention he democratized this sphere, releasing repressed emotions and experiences.

Soon after this action, the national campaign for the victims of domestic violence started in the media and at schools. Yet, for almost ten years, nothing has changed in the case of gays and lesbians. Even worse: hitherto existing silence and hypocrisy in the name of the moral health of family was enforced by the language of ridicule and scorn used by some politicians and journalists, which appeared as reaction to the legalization of same-sex unions in Western Europe. Their attitude legitimizes populist homophobia and, consequently, young people discovering their sexual orientation will be still experiencing the fate of the anonymous young man whose voice sounded in the Market Square.

The example of the public art of Wodiczko signals also a hospitable perspective in which the issue of sexual difference emerged in the Polish context in the 90s. But it is a problematic kind of hospitality. I would call this tendency a humanitarian pedagogy, which – however important and much needed – has its drawbacks. The others are placed in the position of an alienated victim and the society is supposed to feel compassion only for the suffering in the act of solidarity with the victim. As a result the acceptance comes from the position of superiority; pain and marginalization must precede understanding and maybe help. Additionally gay people are placed in the framework of social pathology, such as domestic violence, drug addition and illnesses, which seems to be a potentially dangerous position. As an alternative I would propose humanist pedagogy which is based on deeper understanding and respect for human differences and freedom and on the democratic principle of human rights. And so we are in need of a different philosophy of hospitality: xenology embracing victimology but also going beyond it to the culture of equality. New humanism in Eastern Europe must respond to this demand.

In the Body

Fortunately, there is also a different aspect of the story which started to emerge in the 1990s and came to fruition with my exhibition Love and Democracy in 2005. The other story is more personal, more erotic, but to get to it we must leave the town halls and go out in the streets, and come back to the body. We have to look into the “controversial sexuality.”

The perspective of victimology (the position of the victim) is no longer welcomed by the growing gay and lesbian movement in today’s Poland. The civil rights activities started in the 1980s and the demands for equal rights and visibility in public space have become stronger with each year. The Polish Gay Pride Parade has been organised in Warsaw since 1995, the first Mister Gay Contest took place in 1997. Muscular and beautiful The Male Nude by Krzysztof Malec reflects this new atmosphere, even – and maybe exactly – in the context of exhibition about AIDS.

The beauty and eroticism of male bodies is a frequent theme of gay art. The male nude has flourished in the Western modern visual culture, surely under the impact of the liberalisation of homosexuality. Those tendencies started to influence the visual culture of Poland only in the 90s, mainly in advertising, and then in the arts. There is almost no tradition of full male nude in the history of Polish art, even in the 20th century, and the naked male body was considered pornographic, or even abject under communism.

Thus, together with the Western pop culture, the gay movement and its erotic products began to penetrate the visual sphere of the country very recently, mainly in the last decade. The obviously erotic male body entered Poland through the channel of gay erotica, produced both inside and outside the country. It also means that this kind of images appeared in the dark aura of AIDS. The first publications on homosexuality in the Polish mainstream newspapers in the 80s were about the new epidemic. So it is not a coincidence that the first art exhibition with many examples of homosexual motifs and male nude was devoted to AIDS. Only in this context gay erotic subject in art could find its space and justification and the historians (including me) got a chance to encounter this kind of expression. This is a very telling part of the story!

As a result, the first out-of-the-closet cases of homosexuality in Polish art emerged in an exhibition about bodily and sexual fears and anxieties. There is a long journey from the exhibition I and AIDS to Love and Democracy like two different moments in history and political and artistic consciousness. The context of the show about AIDS immediately inspires a critical reflection about the sexuality. Faced with AIDS, The Male Nude of Krzysztof Malec can be read not only as an affirmative monument of gay desire but also a shrine of its deadly failures, a trap. In the show the male body is caught in the dialectics of oppositions: gay pride and gay tragedy in one emblem, a phantasmal figure at the crossroads of longing and danger, the embodiment of desire and a gravestone angel.

This is how we got the sexual liberation in Eastern Europe in the 1990s, constructed and deconstructed at the same time. From this point of view The Male Nude may be read as a confirmation of the most conventional model of the masculine body, which should be rather rethought and transformed, even contested, not adored or eroticized. It is the frame of the exhibition on AIDS which activates the negative approaches around the sculpture and its gender ideology: a post-gay influx into sprouting Polish homoerotic visuals. In contrast, my exhibition Love and Democracy affirmed the pleasures and emotions of the bodies and placed them in the context of pluralistic equality and sexual rights. The show I and AIDS still looked at the sexual identity from typically Polish sexophobic position and the epidemic functioned as a perfect metaphor for local repression and fears about all-sexual society which started to emerge in new capitalism.

Coming Out

In the mid-1990s, I and AIDS exhibition was also the moment when first openly gay artists appeared in post-communist Polish culture preparing ground for contemporary photographs. Not only Krzysztof Malec, but foremost Andrzej Karas was one of few Polish artists who openly acknowledged his homosexuality. Andrzej Karas treated his sexuality asthe basis of both existential and artistic experience. As he claims he has the same right as straight artists who speak in their art overtly of their eroticism, desire and fascination with the body. This gesture both discursive and creative is enough to make his art rather special in Poland. His coming out was in itself an artistic performance.

The works of Andrzej Karas based upon self-portrait have a self-referential attitude towards sexual and bodily condition of the artist.Iwona Lewandowska, “Andrzej Karas”, Gazeta na Mazowszu. Dodatek Gazety Wyborczej (14 February 1994 ) reprinted in A.r.t: Galeria a.r.t. 1992-1997, Plock, 1998, p.46. A desire of self-manifestation is combined with the desire of healing self-affirmation towards his sexuality and corporeality. His art is a confrontation with external constraint of concealment in the Academy of Fine Arts and internal rules of desire present in the gay world. These rules are specifically the subject of the most interesting work of Andrzej Karas inspired by pornography. Pornography has for him a positive value: the artist removes from it in a liberating way any moralism.I am referring here to an interview with the artist: Katarzyna Kozyra, Artur Zmijewski, “Homoartysta”, Czereja ( 6/1998), pp.5-11.

In a series of three collages set in fetishist frames of red plush the artist placed his own nude in the middle of cut-offs from porn gay magazines. Fragments of exposed masculine bodies overlap creating a whirlpool of desires, a mosaic exploding with sexuality, irritating the viewers, transcending the distance of neutral, aesthetic contemplation. Inside this visual-libidinal pulp, in the centre of this picturesque orgy reigns the naked artist masked in pagan insignia. It is an art emerging from the centre of sexuality; through a whirl of organs and muscles the viewer enters somebody’s auto-erotic dream. Exhibitionism is here the psychological basis of creation. His auto-erotic self-portraits which stage the private fantasies allow Andrzej Karas to create bold homosexual art – unique in Poland. His work is a signal that a self-aware and open gay art has finally started to emerge in Polish visual art, that the movement from coding do explicit message has been completed and might start to influence the new generation.

In Femininity

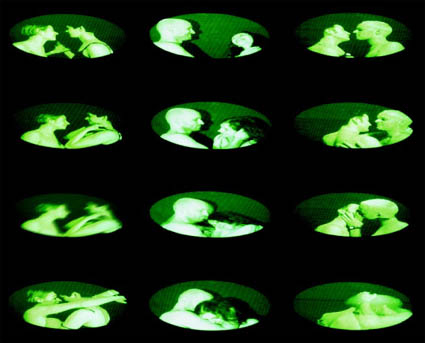

Apart from the works of Krzysztof Malec and Andrzej Karas, the most interesting works concerned with homosexual eroticism proposed in contemporary Polish art were created by women. The first name on the list is that of Katarzyna Kozyra with her video installation The Men’s Bathhouse which represented Poland during the Venice Biennale in 1999. Kozyra, disguised as a man with a false beard and penis, with a hidden camera shot naked men in the Gellert Bathhouse in Budapest, a bath which is also the place of gay cruising.

Contrary to her earlier work The Women’s Bathhouse from 1997, in which the artist concentrated mainly on nude older women she shot with a hidden camera in Gellert, in The Men’s Bathhouse we can mainly see young and attractive men. Many photo reproductions of the work further stress these elements. They tend to be often quite explicit in their presentation of flirting men. The real masculine body is a source of visual pleasure both for the artist and the viewer. The revolution in the ways of perception proposed in The Men’s Bathhouse is based upon the enforcement upon the viewer of a homosexual point of view.

The artist introduces the viewer as one of the participants, into an interplay of gazes full of desire which take place on the screen. Kozyra shows and stresses how often men watch and evaluate each other. She accepts this point herself as a woman putting on a costume of masculinity in order to be able to enter a men’s bathhouse and watch it withoutdisturbing its rituals. In the interviews the artist often clearly stressed the homosexual atmosphere and interplay of erotic looks which incessantly took place there and in which she felt embarrassed to participate only pretending to be a man.Artur Zmijewski, A Passport into the Male Sanctum. An Interview with Katarzyna Kozyra in catalogue of the exhibition Katarzyna Kozyra. The Men’s Bathhouse, XLVIII International Biennale of the Visual Arts, Venice, 1999, pp.75-78. In a fascinating way this embarrassment passes on also to viewers of her art, especially to the masculine part of the audience.

Regardless of the lack of the tradition of the masculine nude in Polish art, and consequently against existing local habits, Kozyra strongly sexualizes the male body both through the feminine and homosexual gaze. It is surprising how few Polish critics who wrote about this installation noticed or commented upon this gay or erotic subtext of her work which the artist discussed freely and with a great sense of humour. Censorship absent in the very work appeared in the sphere of verbalisation; that is, the introduction into the public language.

And here a paradox arises. In 1999, Poland was awarded one of its few prizes during the Venice Biennale, the most prestigious European exposition of contemporary art for a video installation also about a gay meeting place. We should bear in mind that the Biennale is a very nationalist show: art is represented there by states; the video installation of Katarzyna Kozyra represented consequently Poland and Polish culture. Is it not a wonder which bears witness to our liberalisation? The question sounds ironic as with Kozyra’s success a campaign against contemporary art in Poland started with a return to censorship which reached its peak in attacks aimed at Anda Rottenberg, the director of Zacheta art gallery, which ended up in her dismissalTomasz Kitlinski wrote in Art in America that Anda Rottenberg ‘shook up the nation’s male-dominated art establishment’: Tomasz Kitlinski, Warren Niesluchowski, Jacek Maslanka, “Polish Passions Damage Two Works”, Art in America (March 2001), p.160. and with prosecution of Dorota Nieznalska for her installation Passion.

Furthermore, as soon as The Men’s Bathhouse appeared, many oppressive authorities of Polish culture expressed disgust concerning the work of art so highly appreciated in the West. A moment of folly was duly punished, consequences of which still last. We deal here with dangerous territories: humanitarian pedagogy gets a “yes” sometimes, but an affirmation of queer sexuality almost always a “no.”

The Men’s Bathhouse of Katarzyna Kozyra signals a fundamental cultural change in sexuality that, however painful, was taking place in Poland and the stopping of which was not possible. Even despite of this cruel and intolerant part of reality which the action of Wodiczko depicted. Although Kozyra shot the Hungarian’s foreign bathhouse, she introduced her vision into the realm of Polish culture. Her installation was presented in a number of important Polish cultural institutions. It has also entered the popular awareness through massive coverage in artistic press as well as, which is even more important, in pop-culture press.

From a historical point of view it is interesting to compare the video installation of 1999 and a mysterious acrylic picture on paper Die Einsamkeit painted in 1984 by two artists Jaroslaw Modzelewski and Marek Sobczyk from Polish neo-expressionist group Gruppa during their scholarship in Dusseldorf. Both in Kozyra’s work and in the painting we deal with a space dominated by water and nude or half-naked men. In Die Einsamkeit the scenery of a public bath is replaced by an indoor swimming-pool, although a pool is present also in Kozyra’s video-work. In the painting in an absolutely empty and extremely industrial space two men, one of whom is naked, embrace. The atmosphere of the scene is cold and tragic, and the title Loneliness strengthens the drama of alienation.

Modzelewski and Sobczyk have their own story to this strange painting. As they claim it is connected with a friendly, not sexual, identification with two artist’s friends who stayed in Poland and for whom they longed.Jaroslaw Modzelewski, Marek Sobczyk, Szesnascie obrazow, in catalogue of the exhibition Jaroslaw Modzelewski i Marek Sobczyk. Szesnascie wspolnie namalowanych obrazow, Centrum Sztuki Wspolczesnej Zamek Ujazdowski, Warszawa, 1998, p.14. I suggest here a conscious interpretative appropriation. It is my opinion that no gender studies are necessary to notice that no two men embrace in such a manner, especially when they are naked. Actually, why is one of them naked? I would like to concentrate simply on what can be seen as this is the way most viewers shall perceive the painting. And what can be seen is precisely loneliness emanating from the inside of this tragic intimate-erotic relationship of two men. In this isolation there is no authentic closeness: it is not happiness meant for two. The embrace and bodies are clumsy, cut off; the word ‘rejection’ would fit here much better, a total rejection of the world, the people.

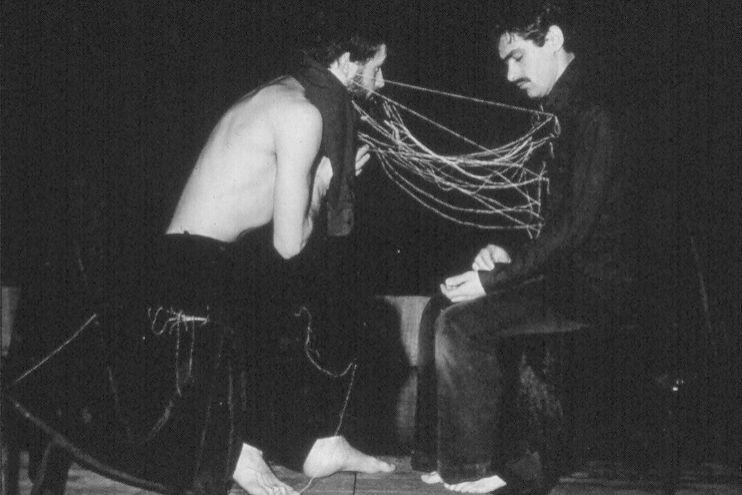

The scene is a quintessence of a homosexual relationship in hostile reality. A vapour of silence emanates from the picture, it is both silence between the partners and walls of silence which cut them off. The vision brought by the artists from Germany in the first half of the 1980s actually reflects Polish attitude towards such homosexual relationship. One perceives reality through one’s own eyes, in a way of perception trained within one’s own society. What the two painters saw several years ago in the beginning of the period of social changes in Eastern Europe differs radically from the contemporary view of Kozyra inspired by Budapest a more developed part of Central Europe.