The Artist as Mediator: An Interview with Marjetica Potrč

Based in Ljubljana and Berlin, Marjetica Potr? deals with issues of social space and contemporary architectural practices, sustainability, and new solutions for communities. Her practice is strongly informed by her interdisciplinary collaborations in research-based, on-site projects, such as Théâtre Evolutif (Bordeaux, 2011), The Cook, the Farmer, His Wife and Their Neighbour (Stedelijk Goes West, Amsterdam, 2009), and Dry Toilet (Caracas, 2003). She translates these investigations into text-based drawings and large-scale architectural installations (“case studies”). Her work has been featured in exhibitions throughout Europe and the Americas, including the São Paulo (1996, 2006) and Venice biennials (1993, 2003, 2009). She has received numerous grants and awards, including the Hugo Boss Prize (2000) and the Vera List Center for Arts and Politics Fellowship at The New School in New York (2007). Since 2011, she has been a professor at the University of Fine Arts/HFBK in Hamburg. See www.potrc.org.

“I have three different practices in my life. One is on-site participatory projects, which I do in collaboration with other professionals and with my students. The second is architectural studies, and the third is drawing narratives.” – Marjetica Potr?

Janeil Engelstad: Could you talk about the role of collaboration in your work? How do you see collaborative and interdisciplinary practices and research contributing solutions to critical problems, such as issues connected to climate change?

Marjetica Potr?: For several years, I have been focused on participatory projects with my students in Hamburg.(Marjetica Potr? teaches a course, Design for the Living World, on participatory practice at HFBK Hamburg / Hochschule für bildende Künste Hamburg http://designforthelivingworld.com.) We do projects using participatory practices in places around the world. In fall 2013, we did a project in Belgrade where we worked with residents of the Savamala neighborhood in the tradition of learning by doing. The students became acquainted with a number of crafts practiced in the neighborhood and learned about the social and economic systems that support the crafts. The goal was to create an open-source manual, an analysis of present-day ways of working and living in Savamala. But we managed to do much more than that. We set up two spaces that the community can now use: Studio KM8, a space for sharing knowledge and skills, and Župa, an old boat docked by the riverbank that is being transformed into a community center.

There are four steps to doing participatory projects: The first step is to listen and talk with the residents where you are working; the second step is to involve the community in the decision making; the third step is to involve the community in the construction process; and the fourth step is co-create with the community a project that they can continue after you leave the site.

JE: Creating a project that is sustainable over the long term.

JE: Creating a project that is sustainable over the long term.

MP: Sustainability is a word that has been overused, and it doesn’t really mean very much anymore. But yes, if you want to engage the power of citizens in shaping the cities they live in, then this is exactly what sustainable development should be about. We try to be on location for two months at a time. This gives the students a chance to understand the site and the people who live there, their challenges and expectations. It also allows them how to change their own perspectives and share knowledge and practices. And then, a magical moment comes when they are able to construct something new in collaboration with the residents.

I am not talking about a new architectural structure; I am talking about social architecture, which for me is very important. We are interested in people. In Savamala, we worked with the residents for two months so they could then start constructing their own spaces. I am talking about place making, not public space. Any group that wants to be recognized in society needs to have a physical space—a place. People often talk about some abstract notion of public space that is good for everyone and so on. But when you talk about place making, you understand that having a space is something down to earth. People need it to ground themselves, their ideas and desires. It is a chance for people to build a community from the ground up; their group identity becomes strong when they can actually build a truly shared space. These bottom-up initiatives are a potential force for democracy.

JE: As you work across countries and the old “East-West” divide, how do you see public space functioning across society today? What differences, if any, do you perceive in the use and role of public space? How do you see the culture, history and/or politics influencing our ideas around the use of public space?

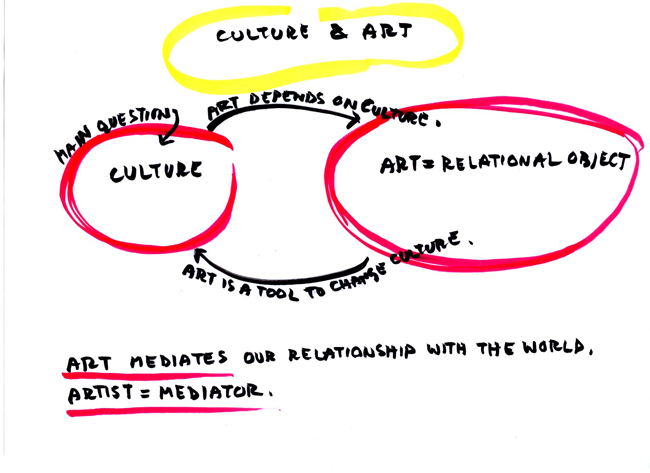

MP: I have never understood the term “public space,” because for me public space has been corrupted. The so-called “public space” is not free and shared by all. My public art projects always happen in a private space or in a community space. In this way, the project becomes a tool for rebuilding the notion of shared space and the idea of what “public” means. What is happening in European cities, both East and West, is that you have this amazing push for community gardens. The important thing about community gardens is not only the cultivation of a city’s green spaces and growing vegetables, but also the fact that they are actual political schoolrooms where you can reclaim your community, reclaim your neighborhood, and reclaim your city. It is a simple process that originates in people engaging with the community garden. Community gardens have become relational objects: they are tools for changing the culture of living.(For additional discussions of community gardens in this special edition of ARTMargins Online, see the projects by Budapest Farmer’s Hack, Nina Czegledy and Matej Vakula.)

MP: I have never understood the term “public space,” because for me public space has been corrupted. The so-called “public space” is not free and shared by all. My public art projects always happen in a private space or in a community space. In this way, the project becomes a tool for rebuilding the notion of shared space and the idea of what “public” means. What is happening in European cities, both East and West, is that you have this amazing push for community gardens. The important thing about community gardens is not only the cultivation of a city’s green spaces and growing vegetables, but also the fact that they are actual political schoolrooms where you can reclaim your community, reclaim your neighborhood, and reclaim your city. It is a simple process that originates in people engaging with the community garden. Community gardens have become relational objects: they are tools for changing the culture of living.(For additional discussions of community gardens in this special edition of ARTMargins Online, see the projects by Budapest Farmer’s Hack, Nina Czegledy and Matej Vakula.)

JE: And in that place, is the artwork the change? It is the result of your actions, rather than the action itself, which can come from project-based work?

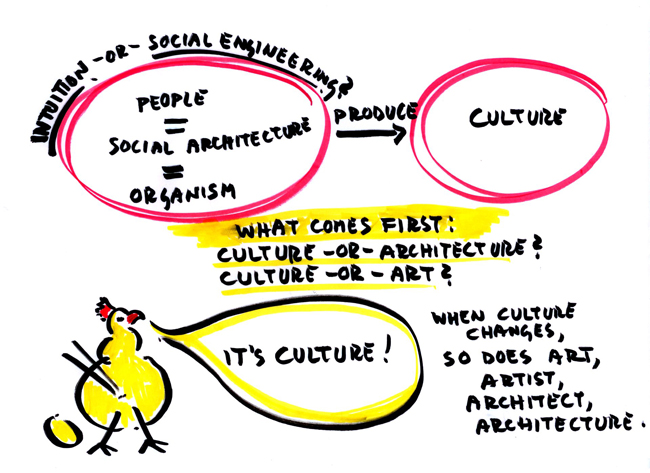

MP: I made two drawings titled Notes on Participatory Design that illustrate the relationships between art and culture. Art is a tool to change culture, and when culture changes, it follows that the artist, art, and architecture also change.

JE: In 2006, you participated in The Lost Highway Expedition (LHE), where over 300 artists traveled through nine cities in the Western Balkans and engaged in cultural production. You created both drawing narratives and architectural case studies in response to this research trip; much of it in response to the famous, highly decorated houses in Tirana and Prishtina. Could you talk about this project, the work that emerged and how you see the houses functioning in society? Do these colorful expressions merely reflect people’s creativity and individualism, or do they collectively hold people together in a way that builds and strengthens community in the post-socialist era?

MP: When we traveled in the Western Balkans it was after the war and the political changes. People were still talking about the war, but no one was talking about the society that was being built after the war, or the values of the society that was building the new cities. In many places, there was a lack of engagement by the state, and this created a need for self-organization by people on the ground and for the reconstruction of the society. The crazy, decorated houses we saw were proud houses. By constructing their homes in personalized styles—pseudo-Byzantine, pseudo-Oriental, and so on—the residents were celebrating the new society they were co-creating. ??? ??????? ?????? ???????? ? ???? ???? These were architectural archetypes that alluded to the distant past. This was definitely not about modernism. It was about individualism, but not the individualism of the modernist state of mind that celebrated equality. On the Lost Highway Exhibition we saw a new citizenship being born on the ruins of the socialist state. And we asked ourselves whether citizens in the European Union could learn anything from the reconstruction of the Balkans. As we are talking now, I remember the inaugural speech by the new king of the Netherlands a few months ago. He said that the welfare state of the twentieth century is over. In its place there is an emerging “participation society,” where people must take responsibility for their own future while the role of the state diminishes.(In an address to the Dutch parliament on September 17, 2013, King Willem-Alexander talked at length about the end of the Dutch welfare state: “The shift towards a participation society is especially visible in our systems of social security and long-term care. In these areas in particular, the classical post-war welfare state produced schemes that are unsustainable in their present form and which no longer meet people’s expectations.” For the full text of this speech see: http://www.koninklijkhuis.nl/globale-paginas/taalrubrieken/english/speeches/speeches-from-the-throne/speech-from-the-throne-2013.) This sounds a lot like what we saw on the LHE in 2006.

MP: When we traveled in the Western Balkans it was after the war and the political changes. People were still talking about the war, but no one was talking about the society that was being built after the war, or the values of the society that was building the new cities. In many places, there was a lack of engagement by the state, and this created a need for self-organization by people on the ground and for the reconstruction of the society. The crazy, decorated houses we saw were proud houses. By constructing their homes in personalized styles—pseudo-Byzantine, pseudo-Oriental, and so on—the residents were celebrating the new society they were co-creating. ??? ??????? ?????? ???????? ? ???? ???? These were architectural archetypes that alluded to the distant past. This was definitely not about modernism. It was about individualism, but not the individualism of the modernist state of mind that celebrated equality. On the Lost Highway Exhibition we saw a new citizenship being born on the ruins of the socialist state. And we asked ourselves whether citizens in the European Union could learn anything from the reconstruction of the Balkans. As we are talking now, I remember the inaugural speech by the new king of the Netherlands a few months ago. He said that the welfare state of the twentieth century is over. In its place there is an emerging “participation society,” where people must take responsibility for their own future while the role of the state diminishes.(In an address to the Dutch parliament on September 17, 2013, King Willem-Alexander talked at length about the end of the Dutch welfare state: “The shift towards a participation society is especially visible in our systems of social security and long-term care. In these areas in particular, the classical post-war welfare state produced schemes that are unsustainable in their present form and which no longer meet people’s expectations.” For the full text of this speech see: http://www.koninklijkhuis.nl/globale-paginas/taalrubrieken/english/speeches/speeches-from-the-throne/speech-from-the-throne-2013.) This sounds a lot like what we saw on the LHE in 2006.

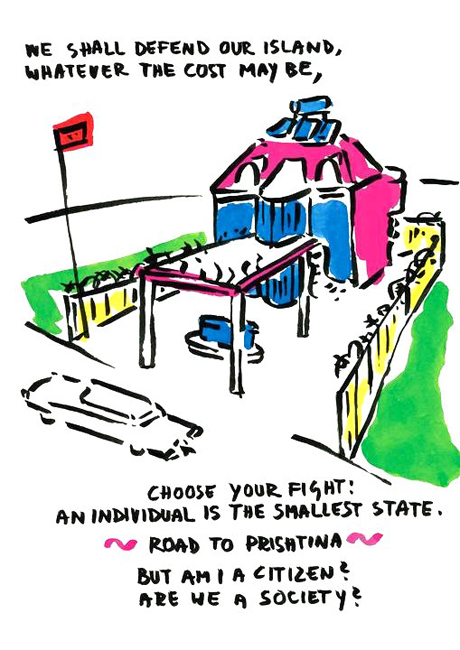

The crucial experience for me was when we entered Prishtina, the capital of Kosovo. At the time there were three layers of government: the United Nations government, the Serbian government, and the Kosovo government. What this meant, in short, was that no one really ruled and, basically, the individual became the smallest state. Each person who lived there, who was constructing his life, his house and his territory—he was the smallest state. I reflected on this in a drawing that is part of my Struggle for Spatial Justice series (2005-2007). The text in the drawing is taken from a speech by Winston Churchill where he talks about the defense of the city. The illustration is a family house with a business out front—a gas station. It is fenced off and at the edge there is a flag that marks the territory. The house celebrates the existence of its builder, but it also celebrates the fragmentation of the socialist state. On the LHE, we encountered fragmentation again and again. One example is the fragmentation of territories: think of how Yugoslavia became seven new states—small-scale territories. Another example we saw was the shrinking of residential communities. In Socialist Yugoslavia you had apartment-block neighborhoods where 10,000 people lived together; by 2006, you had ten or fifteen families living together in clusters called urban villas. While these apartment blocks still exist, the trend was towards smaller micro-communities living in smaller housing developments. But is it possible that fragmentation is another way of saying “de-growth,” a word we use when we talk about sustainable communities?

The crucial experience for me was when we entered Prishtina, the capital of Kosovo. At the time there were three layers of government: the United Nations government, the Serbian government, and the Kosovo government. What this meant, in short, was that no one really ruled and, basically, the individual became the smallest state. Each person who lived there, who was constructing his life, his house and his territory—he was the smallest state. I reflected on this in a drawing that is part of my Struggle for Spatial Justice series (2005-2007). The text in the drawing is taken from a speech by Winston Churchill where he talks about the defense of the city. The illustration is a family house with a business out front—a gas station. It is fenced off and at the edge there is a flag that marks the territory. The house celebrates the existence of its builder, but it also celebrates the fragmentation of the socialist state. On the LHE, we encountered fragmentation again and again. One example is the fragmentation of territories: think of how Yugoslavia became seven new states—small-scale territories. Another example we saw was the shrinking of residential communities. In Socialist Yugoslavia you had apartment-block neighborhoods where 10,000 people lived together; by 2006, you had ten or fifteen families living together in clusters called urban villas. While these apartment blocks still exist, the trend was towards smaller micro-communities living in smaller housing developments. But is it possible that fragmentation is another way of saying “de-growth,” a word we use when we talk about sustainable communities?

JE: Many artists doing project-based work aim to create new ways of making the future civil society. In your three different levels of engagement—on-site participatory projects, architectural case studies and drawing narratives—what is your position as an artist? Does it shift from medium to medium, from project to project?

MP: In all of my on-site work, I consider myself a mediator. That’s quite easy. The architectural case studies and drawings supplement it. Contemporary art is a living language. It changes when the culture changes. And when the culture changes, the role of the artist changes as well.

This interview took place via Skype in January 2014.