Socialist Realist Graphic Art in Albania (Book Review)

Maks Velo, Grafika e Realizmit Socialist në Shqipëri / Socialist Realist Graphic Art in Albania, Tirana: Emal, 2014, 305 pp.

One of the great questions confronted by any history of art in the twentieth century, and particularly of the art of Eastern Europe, is that of the artistic significance of Socialist Realism and the issues surrounding its legacy. This is especially true in Albania, one of the countries where Socialist Realism persisted as the dominant style for more than forty years—especially during the period (1944-1985) whenthe country was led by socialist dictator Enver Hoxha. In Albania, the question of Socialist Realism’s legacy is partially one of public space, due to the large number of monuments and works of architecture remaining from the socialist era. However, it is also more broadly a question of the academic and social history of the nation’s cultural production, and the possibilities for Socialist Realism to be seen in dialogue with the new forms and ideologies of contemporary art. These possibilities have been explored in recent exhibitions such as Workers Leaving the Studio, Looking Away from Socialist Realism, at the National Gallery of Arts in Tirana in 2015, and, more indirectly, in the installation of Armando Lulaj’s works in the Albanian Pavilion at the 2015 Venice Biennale.(The exhibition, which ran February 27 – April 5, 2015, was curated by Mihnea Mircan and juxtaposed the works of contemporary artists like Armando Lulaj, Ciprian Mure?an, IRWIN, and Jonas Staal with works from the National Gallery’s collection, by artists like Thoma Thomai, Muntas Dhrami, Anastas Konstandini, and Sali Shijaku. See http://departmentofeagles.org/portfolio_page/workers-leaving-the-studio-looking-away-from-socialist-realism/ (accessed March 15, 2015). Previous exhibitions at Tirana’s National Gallery, such as The Painting of Modern Life, curated by Alban Hajdinaj in 2011, likewise juxtaposed Socialist Realist works against both older and more recent examples of Albanian art that might be described as “realist” at least in their referential character. For a discussion of Armando Lulaj’s works (including some that appeared both in Workers Leaving the Studio and in the Albanian Pavilion in Venice) in relation to the legacy of Albanian Socialist Realism, see Vincent W.J. van Gerven Oei, “The Production of Hrönir: Albanian Socialist Realism and After,” in Workers Leaving the Studio. Looking Away from Socialist Realism (New York: Punctum, 2015), pp. 191-207.)

Perhaps most importantly, the history of Socialist Realism in Albania cannot be separated from the construction of Albanian national identity, which was—by no means entirely, but to a significant extent—constructed during the socialist period.(For a general introduction to the relationship between the socialist period and the construction of Albanian national(ist) identity, see Fatos Lubonja, “Between the Glory of a Virtual World and the Misery of a Real World,” in Albanian Identities: Myth and History, ed. Stephanie Schwandner-Sievers and Bernd J. Fischer (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2002), pp. 91-103.) Therefore, as art theorist and historian Gëzim Qëndro points out, the image of socialism’s “New Man” was an important factor in the creation of a collective, imagined community of the Albanian people.(Gëzim Qëndro, “Wie Heisst Du, Marionette?” in Harald Szeeman, et al., Blut & Honig: Zukunft ist am Balkan (Klosterneuburg: Edition Sammlung Essl, 2003), pp. 72-79.) As many contemporary Albanians seek to confirm their identity as Europeans in the country’s bid for EU membership, the confrontation with the socialist past has achieved a heightened level of reification (or museumification) in the past year. This period has seen the creation of new museums devoted to working through the traumas of Albania’s long period of political isolation, including the opening of the hybrid museum/art installation space Bunk’Art, housed in a large underground bunker on the outskirts of Tirana.(See “Hapet për publikun bunkeri i fshehtë anti-bërthamor i ish-diktatorit Hoxha,” Shqiptarja, November 22, 2014, available from: http://www.shqiptarja.com/kulture/2730/hapet-per-publikun-bunkeri-i-fshehte-anti-berthamor-i-ish-diktatorit-hoxha-254335.htm (accessed June 13, 2015).) As Bunk’Art’s name suggests, however, the issue is not simply one of confronting the socialist past as a matter of history: it isa matter of culture and art as well, a matter of matching creative output to the task of remembering socialism. In this context, the concrete cultural production of the socialist period presents a particularly fraught historical and ideological territory. As Albania attempts to assert its claim on the histories and memories of the European continent,(For a concise statement of the claim that adopting the correct tactics of cultural memory production will link Albania firmly to the legacy of Europe, see Falma Fshazi, “Kufiri i kujtesës,” Gazeta Dita, January 26, 2015, available from: http://www.gazetadita.al/kufiri-i-kujteses/ (accessed January 30, 2015).) the legacy of Socialist Realism poses serious questions about the ways in which Albanian cultural production belongs and relates to major narratives of twentieth-century Western and Eastern European culture (such as the rise of Modernism, the political radicality of various avant-gardes, and the perceived globalism of contemporary art).

While the painting and sculpture of Albanian Socialist Realism have been the subject of (albeit still quite limited) study, drawings and prints produced in socialist Albania have received relatively little attention. A few books published during the socialist years have highlighted achievements in printmaking and the poster arts.(The most notable is, perhaps Artet Figurative në Republikën Popullore të Shqipërisë [The Figurative Arts in the Popular Republic of Albania] (Tirana: Naim Frashëri, 1969). The more recent survey by Ferid Hudhri, Albanians in Art (Tirana: Onufri, 2003)—the only survey available in English—does not feature the graphic arts.) Yet thus far, no scholarly survey of Albanian socialist graphic art exists. Not least for this reason, Maks Velo’s Socialist Realist Graphic Art in Albania is a monumental endeavor: it attempts to provide a sweeping visual overview of graphic production in Albania during socialism, highlighting the important artists, themes, and techniques of this art. Velo, known in Albania as a respected architect under socialism who was later imprisoned by the regime for his “modernist” leanings, has become one of the primary champions for the preservation of official socialist art in the context of post-socialist Albania. His new book aims to present readers with an introduction to the most significant practitioners of drawing and printmaking from the socialist period (Sadik Kaceli, Foto Stamo, Abdurrahim Buza, Naxhi Bakalli, Zamir Mati, Lumturi Dhrami, Safo Marko, Pandi Mele, Anastas Konstandini, and others), reflecting the aesthetic variety of graphic works published in popular newspapers and magazines.

While the painting and sculpture of Albanian Socialist Realism have been the subject of (albeit still quite limited) study, drawings and prints produced in socialist Albania have received relatively little attention. A few books published during the socialist years have highlighted achievements in printmaking and the poster arts.(The most notable is, perhaps Artet Figurative në Republikën Popullore të Shqipërisë [The Figurative Arts in the Popular Republic of Albania] (Tirana: Naim Frashëri, 1969). The more recent survey by Ferid Hudhri, Albanians in Art (Tirana: Onufri, 2003)—the only survey available in English—does not feature the graphic arts.) Yet thus far, no scholarly survey of Albanian socialist graphic art exists. Not least for this reason, Maks Velo’s Socialist Realist Graphic Art in Albania is a monumental endeavor: it attempts to provide a sweeping visual overview of graphic production in Albania during socialism, highlighting the important artists, themes, and techniques of this art. Velo, known in Albania as a respected architect under socialism who was later imprisoned by the regime for his “modernist” leanings, has become one of the primary champions for the preservation of official socialist art in the context of post-socialist Albania. His new book aims to present readers with an introduction to the most significant practitioners of drawing and printmaking from the socialist period (Sadik Kaceli, Foto Stamo, Abdurrahim Buza, Naxhi Bakalli, Zamir Mati, Lumturi Dhrami, Safo Marko, Pandi Mele, Anastas Konstandini, and others), reflecting the aesthetic variety of graphic works published in popular newspapers and magazines.

Socialist Realist Graphic Art in Albania contains hundreds of examples of drawings, prints, and posters created during Albania’s socialist period, as well as a small number of images of postage stamps, journal covers, and even typography. In a few cases, photographs show the original context of posters and placards, but in general the context of the works remains a bit mysterious (a problem that haunts the entire book, and to which I return below). The images of the drawings and prints are primarily in black and white, while most, but not all, of the posters are shown in color. The quality of the images varies tremendously, but they are unfortunately, on the whole, quite poor. Many appear to have been reproduced from photographs rather than scans, and they are often blurry or even bitmapped. To a degree, since many of the works featured in the book were only ever available in reproduction (in the various journals and magazines produced by the socialist government), this double mediation seems conceptually appropriate. The quality of the printing in Albanian socialist-era periodicals was often low, and so readers at the time sometimes encountered graphic works in reproductions that were blurry or washed out. However, the generally poor quality of Velo’s scans and photos does not simply draw attention to these real effects of printed reproduction – it worsens them, making it in fact more difficult to determine the quality of the original images, and sometimes making parts of them completely illegible. This ultimately defeats two of Velo’s primary stated goals in the publication: to consider the aesthetic merit of the artworks in question, and to interpret their role in and relation to the official ideology of their time.

Socialist Realist Graphic Art in Albania contains hundreds of examples of drawings, prints, and posters created during Albania’s socialist period, as well as a small number of images of postage stamps, journal covers, and even typography. In a few cases, photographs show the original context of posters and placards, but in general the context of the works remains a bit mysterious (a problem that haunts the entire book, and to which I return below). The images of the drawings and prints are primarily in black and white, while most, but not all, of the posters are shown in color. The quality of the images varies tremendously, but they are unfortunately, on the whole, quite poor. Many appear to have been reproduced from photographs rather than scans, and they are often blurry or even bitmapped. To a degree, since many of the works featured in the book were only ever available in reproduction (in the various journals and magazines produced by the socialist government), this double mediation seems conceptually appropriate. The quality of the printing in Albanian socialist-era periodicals was often low, and so readers at the time sometimes encountered graphic works in reproductions that were blurry or washed out. However, the generally poor quality of Velo’s scans and photos does not simply draw attention to these real effects of printed reproduction – it worsens them, making it in fact more difficult to determine the quality of the original images, and sometimes making parts of them completely illegible. This ultimately defeats two of Velo’s primary stated goals in the publication: to consider the aesthetic merit of the artworks in question, and to interpret their role in and relation to the official ideology of their time.

The book contains a brief introduction (in three languages: Albanian, English, and French), wherein Velo provides a summary of the volume’s contents and an overview of the historical situation of Socialist Realist graphic art in Albania. As Velo points out, the graphic arts (chiefly drawing, printmaking and poster design) were indispensible to Socialist Realism’s project of creating the beautiful “mirage” of Albanian socialist life, since they accompanied people everywhere: they adorned the walls of collective eating halls, appeared on the exteriors of apartment complexes, decorated official buildings during celebrations such as International Workers’ Day, and became a mainstay of periodical publications that were read in the home on a regular basis.(Velo, Grafika e Realizmit Socialist në Shqipëri / Socialist Realist Graphic Art in Albania (Tirana: Emal, 2014) pp. 5-6.) The supplemental role of the graphic arts (as illustration, as clarification, and as decoration), vis-à-vis literary and journalistic texts, public events, and the built and lived environment, suggests the full scope of the totalizing context of life under socialism—where even the smallest word, image, or event could be marshaled to carry tremendous ideological weight. However, this supplementarity also shows that the outlines of this totalizing context were shifting and ambiguous. Indeed (although Velo completely ignores this possibility), the reader is tempted to hypothesize that it was precisely the flexibility of the graphic arts—specifically, their ability to effectively encompass both narrative progression and the eternal, mythic quality of the established symbol—that made them ideal for the simultaneous construction and reflection of socialist existence.

The works included in Socialist Realist Graphic Art in Albania run the gamut from cycles of drawings depicting the nation’s industrialization, to sketches depicting village customs, to series of prints chronicling Albanian history, to abstracted images of the elusive “New Man,” the hero of utopian life to come. This breadth hints at the complicated relation of art to the multifaceted process of building a socialism that was both universal and nationally specific, and it also presents a challenge for interpretation and categorization. In the introduction, Velo attempts to establish some of the possibilities for a framing typology of the art contained in the book, providing a structure similar to (though of course much more modest than) that offered by Igor Golomstock in Totalitarian Art.(See Totalitarian Art: In the Soviet Union, the Third Reich, Fascist Italy, and the People’s Republic of China, trans. Robert Chandler (New York: Overlook Duckworth, 2011), pp. 216-65.) It is here that Velo confronts a difficulty that he refuses to fully acknowledge—just how should one go about categorizing Socialist Realist cultural production? The book’s introduction offers, in asense, three answers, but makes no attempt to synthesize them. In the first paragraph of the introduction, Velo suggests that the graphic art of Socialist Realism can be analyzed based on: (1) technical criteria, (2) ideological content, or (3) its function in terms of a target audience and material context. The book itself proceeds along the lines of medium by dividing the works into drawings, prints, and posters, presenting a brief historical discussion of each of these groups. However, within these categories, which coincide with the book’s chapters, images are arranged neither in terms of context nor strictly in terms of chronology, but by artist. Indeed, a significant part of Velo’s enterprise is also to establish a canon of the most significant Albanian artists working in graphic media during the socialist years. This is without a doubt a necessary and admirable goal for a publication, but a fuller understanding of the motivations and strategies of the artists in question is marred by the dearth of contextual and historical information included. This lack of information also hampers the book’s broader goal, since it impedes a general understanding of just how the aesthetic characteristics of Socialist Realist graphic art in Albania were related to official ideology.

The most glaring omission in the compilation of the images is the complete absence of information about where and when particular works were published. Dates (to say nothing of titles, or the short descriptions that sometimes accompanied prints and drawings in socialist-era Albanian publications) are only occasionally present, and while Velo’s introduction makes reference to the pertinent publications where these works first appeared (such as Drita,(Drita (“The Light)” was originally the name of one of the first publications in the Albanian language, initially published in 1884 in Istanbul by Petro Poga. Drita contained literary and educational pieces, often authored by figures who would later become key members of the Albanian National Awakening (such as the Frashëri brothers). The publication drifted in and out of print through the first part of the twentieth century. Eventually, following World War Two, it became the official weekly publication of the Albanian Union of Writers and Artists. See Aleks Buda, et al., Historia e Popullit Shqiptar, Vëllimi i Dytë: Rilindja Kombëtare, Vitet 30 të Shek. XIX – 1912 (Tirana: Toena, 2002) p. 249-250.) Nëntori,(Nëntori (“November”) was the monthly journal of the Albanian Union of Writers and Artists. It began publication in 1953, and featured essays of literary and artistic criticism, translations, poetry, and occasionally photographs and reproductions of paintings, drawings, and prints, often highlighting the work of a particular artist).) and Ylli(Ylli (‘The Star’) was the primary full-color glossy magazine published from 1951 to 1991 in socialist Albania. Its content covered politics, science, leisure, and culture. For a critical analysis of the publication, see Anouck Durand and Gilles de Rapper, Ylli: Les couleurs de la dictature (Paris: 2012), available from: http://www.idemec.cnrs.fr/ spip.php?article239&lang=en (accessed March 16, 2015).)), he gives no contextual information for individual images.(For those familiar with the typefaces used in the different publications, it is possible to extrapolate, at least, which journal or magazine a particular work was published in, if and when Velo reproduces the accompanying caption along with the image. However, this is still relatively unhelpful in terms of chronology and therefore in terms of further research.) This is frustrating, since it seems that (given Velo’s clearly impressive archive of images) it would have been quite simple, if time consuming, to give the reader at least this much. The absence of publication information makes it impossible to trace the careers or artistic development of individual artists or to understand the ideological function of particular works in terms of their target audience or their role in relation to their printed context. Furthermore, without a clear chronology, it is difficult to establish any broader trends in either artistic style or themes within the corpus Velo presents.

As a result, Velo’s project ultimately participates in a mode of cultural history that is unfortunately common in relation to Eastern Europe: the decontextualization of Socialist Realism. This decontextualization takes many forms, the most common of which is the movement’s excision from general narratives of Eastern European art. Typically deemed neither “modernist” nor “avant-garde” (nor, for that matter, “contemporary”), Socialist Realism is often only mentioned and illustrated in passing in major surveys published in Europe and America dealing with twentieth-century Eastern European art.(For example, Socialist Realism is mentioned only in passing in works such as Steven A. Mansbach, Modern Art in Eastern Europe from the Baltic to the Balkans, ca. 1890-1939 (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1999); Piotr Piotrowski, In the Shadow of Yalta: Art and the Avant-garde in Eastern Europe, 1945-1989, trans. Anna Brzyski (London: Reaktion, 2009); Dubravka Djuri? and Miško Šuvakovi?, eds., Impossible Histories: Historical Avant-gardes, Neo-avant-gardes, and Post-avant-gardes in Yugoslavia, 1918-1991 (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2003); Laura Hoptman and Tomáš Pospiszyl, eds., Primary Documents: A Sourcebook for Eastern and Central European Art since the 1950s (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2002); and IRWIN, eds., East Art Map: Contemporary Art in Eastern Europe (New York: Afterall, 2006). While the absence of Socialist Realism from these publications is understandable, it also reveals the need to more rigorously address the contextual interrelationship of Socialist Realism to Modernism and the Avant-gardes (of all varieties) in Eastern European nations other than Russia (where this project of tracing the relationship of official and unofficial art under socialism has been addressed more completely in the scholarship).) Thus, Socialist Realism (and it is the Soviet variety that continues to receive the most historical and theoretical attention) is mostly treated as a separate issue, the subject of books and exhibitions dealing exclusively with that topic.(See, for example, Matthew Cullerne Bown’s monumental Socialist Realist Painting (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1998), or his earlier and more general Art Under Stalin (New York: Holmes & Meier, 1991), as well as exhibition catalogs like Bown, et al., Socialist Realisms: Soviet Painting 1920-1970 (New York: Rizzoli, 2012) and Boris Groys and Max Hollein, eds., Traumfabrik Kommunismus: die visuelle Kultur der Stalinzeit (Frankfurt: Schirn Kunsthalle Frankfurt, 2003).) This bracketing of Socialist Realism—in the wake of Boris Groys’ now famous assertion that the style was first developed by elites who “assimilated the experience of the avant-garde” and was conceived according “to the internal logic of the avant-garde method itself”(Boris Groys, The Total Art of Stalinism: Avant-Garde, Aesthetic Dictatorship, and Beyond, trans. Charles Rougle (New York: Verso, 2011), p. 9.)—has given way to another kind of decontextualization, one in which Socialist Realism is seen as the context itself, rather than a product of any dialectical or dialogic process. In other words, following the popularization of the idea that Socialist Realism provided the background for the pioneering maneuvers and strategies of postmodern (or “post utopian,” as Groys calls it) Eastern European art, it has often been treated as a kind of originary foil against which more recent trends develop.(One example of this, dealing with the Russian case, is Margarita Tupitsyn, Margins of Soviet Art: Socialist Realism to the Present (Milan: Giancarlo Politi Editore, 1989); Victor Tupitsyn’s more recent The Museological Unconscious: Communal (Post)Modernism in Russia (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2009) likewise begins its narrative with a brief discussion of the dreamworld of Soviet Socialist Realism before delving into the exploits of artists reacting against that dreamworld. Such histories raise a great number of important questions about how artists grappled with Socialist Realism, but they also participate in a kind of flattening out of Socialist Realism that ignores, among other things, the challenges it faced as an art that needed to be at once transnational (and utopically global) and regionally (or nationally) specific.) These trends, in turn, take on an implied quality of innovation by dint of the perceived contrast with the backdrop of Socialist Realism’s constraining effects.(This kind of thinking, in which Socialist Realism is an undesirable and vague origin to be heroically resisted and escaped, also plays easily into contemporary Albanian political discourses such as those surrounding Bunk’Art, which emphasize the socialist past solely as a shared trauma to be escaped in the move towards Western European democracy and capitalism.)

The treatment of Socialist Realism as either a separate narrative from that of twentieth-century Modernism in Eastern Europe or as the monolithic ground against which postwar avant-gardes reacted has produced a need for the re-contextualization of Socialist Realism, forming part of a larger historical project of the reevaluation of Realism as an artistic paradigm.(A recent example of this attempt to create a new narrative of Realism’s significance in the twentieth century is Alex Potts’ Experiments in Modern Realism: World Making, Politics, and the Everyday in Postwar European and American Art (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2013), which recasts many of the (both abstract and figurative) trends of postwar art as manifestations of a fundamentally Realist enterprise. Potts, however, still sees Socialist Realism as too “conventional” to partake in the radicality of other postwar art, and so he largely sets it aside. See Potts, Experiments in Modern Realism, pp. 27-29.) This recontextualization generally takes the form of investigations into how audiences can read Socialist Realism today, and how it can speak to contemporary art.(The exhibition noted at the outset of this review (Workers Leaving the Studio, Looking Away from Socialist Realism, at the National Gallery in Tirana) represents one of these recent efforts. Earlier exhibitions, such as Blut & Honig: Zukunft ist am Balkan (in 2003) also juxtaposed works of contemporary Eastern European artists with an installation of Albanian Socialist Realism (although this juxtaposition was not the primary focus of that exhibition, as it was with Workers Leaving the Studio). See Harald Szeeman, et al., Blut & Honig: Zukunft ist am Balkan (Klosterneuburg: Edition Sammlung Essl, 2003), pp. 72-79.)This territory, of course, is also fraught, since it risks too strongly foregrounding the timeless and utopian goals of Socialist Realism, but it does have the virtue of treating works in this style as part of an ongoing narrative of art in the present. Velo also clearly believes that the time is ripe for a recontextualization of Socialist Realism, precisely because, he says, its original context is utterly lost to us.(However, the absence of original context is, in the case of his book, partially imposed precisely by the absence of information that in many cases is still in fact available to those with access to the original publications. Unfortunately, Velo believes that the loss of the Socialist Realist context is a foregone conclusion, and therefore he is content to set aside the scholarly work that would—always partially, of course—preserve it.) In his introduction, he writes, “our graphic art was ideological and it died the moment ideology died.”(Velo, Grafika e Realizmit Socialist në Shqipëri, p. 12. This statement is not so much outrageous for the assertion that Socialist Realist art is “dead,” but for the implication that we live in a “post-ideological” moment.) Thus, from the outset, Velo’s book asserts its postmortem endeavor: Socialist Realism is well and truly dead, and its achievements must be valued precisely because we no longer have access to the world they reflected and shaped. However, this distance also makes the works, allegedly, easier to understand; Velo writes that “today, graphic art is the only art form [from the socialist period] that can be easily interpreted.”(Ibid., p. 5.)

Of course, the variety of works on display in Socialist Realist Graphic Art in Albania precisely denies the ease of any single reading: their diversity (heightened, it is true, by their lack of context) seems to testify not so much to the failure of the socialist project as to its rich aesthetic aspects and possibilities. From Safo Marko’s prints commemorating the Albanian women who died for the partisan cause, to Petrit Kumi’s photomontage juxtaposing Hektor Dule’s well-known sculpture Në Njërën Dorë Kazmën, në Tjetrën Pushkën [In One Hand the Pickaxe, in the Other the Rifle] with factory smokestacks and jubilant crowds, the works witness artists adapting contemporary cultural imagery and national history in new ways, developing viewpoints that are sometimes nostalgic and, at other times, aimed directly at the future. Velo is no doubt aware of the works’ potential to escape the official ideology of their production; he has elsewhere contradicted his statements in the book’s introduction and, instead, asserted that the graphic arts often “escaped the control of official committees because they were considered minor arts,” not important enough to warrant strict regulation.(“Maks Velo promovon grafikat e realizmit socialist në Paris,” Koha Jonë, November 12, 2014, available from: http://kohajone.org/index.php/kultura/item/1687-maks-velo-promovon-grafikat-e-realizmit-socialist-ne-paris (accessed March 18, 2015).) The truth, of course, is not simply that many of the works included in Velo’s book “escape” ideology, but that they broaden our understanding of the interdependent discourses at play in the visual arts of socialist Albania.

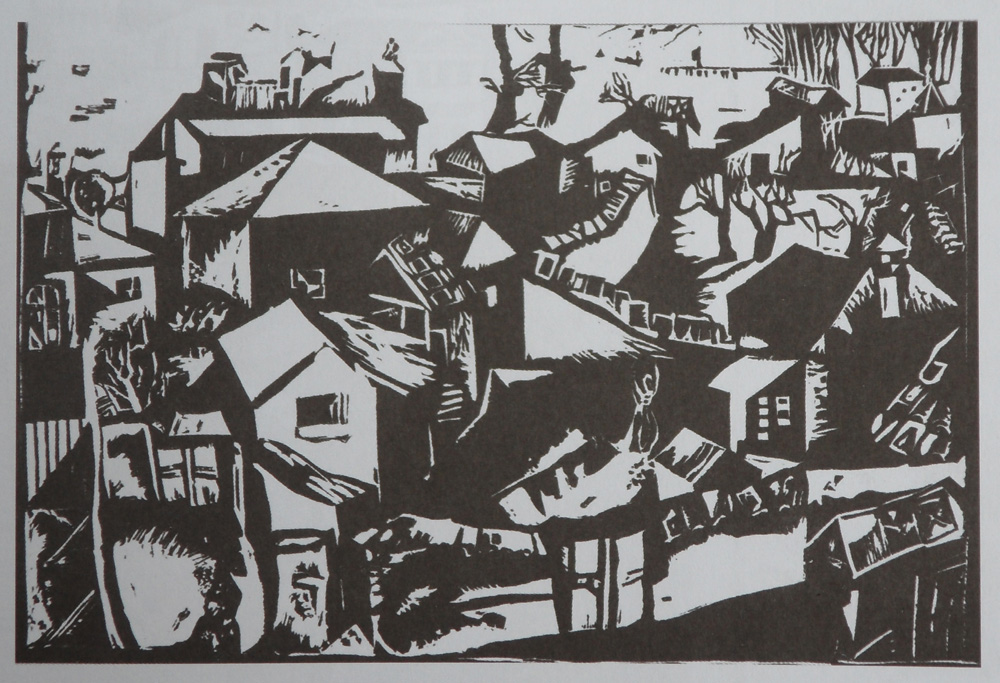

![Skënder Kamberi, “Kooperativistja [Cooperative Farm Worker]” and “Rapsodi [Rhapodist],” ink sketches. In Maks Velo, Grafika e Realizmit Socialist në Shqipëri (Tirana: Emal, 2014), p. 80. Photograph by Maks Velo. Courtesy of Maks Velo.](https://artmargins.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/04/Figure_2_Skender_Kamberi.jpg) Neither evidence of a romanticized aesthetic rebellion against official art, nor of slavish adherence to official principles, the works in Socialist Realist Graphic Art in Albania reveal the complicated navigation between these two extremes. This is, perhaps, most evident in the drawings presented, where the tentative character and frequent incompleteness of the works resists a single, conclusive ideological message. The free and vigorous lines in Skënder Kamberi’s sketches, for example, give his figures an emotional charge that derives from our uncertainty about their thoughts and emotions. On the one hand, this uncertainty makes them seem ready to be filled in by the ideological goals of the Party, but at the same time it indexes the gap that remains between those ideological goals and the everyday experience of Kamberi’s individual subjects. This ambivalence is also present in many of the landscapes and cityscapes. In some images of villages, such as Bujar Zajmi’s engravings, the emphasis is undeniably on the transformation imposed on nature by the Party, evidenced by propagandistic signs and geoglyphs that serve to make the landscape literally readable, as well as by the traces of agricultural work. Elsewhere, however, in some of the works of Pandi Mele or Roland Karanxha, for example, the connection between workers and the landscape appears as an abundant condition that exceeds the Party’s reach. Of course, this is, in part, simply ideology masking itself behind an idyllic image of the freedom of rural life, but it also produces a space where different sources of meaning (individual village traditions, the aesthetic encounter with landscape) become available to viewers. Likewise, in cityscapes of Albania’s oldest cities, such as Berat and Gjirokastra, with their dense Ottoman architecture, the city’s Cubist forms present a picture plane lacking the clear hierarchal organization endemic to many Socialist Realist images. The same is true of Anastas Konstandini’s jumbled views of village streets, which likewise deny organization around a central, monumental structure. The point, again, is not that these images actively resist totalizing ideologies, but that their meanings exceed strictly utilitarian, propagandistic goals. Unfortunately, Velo himself never comments on the potential openness, or duality, present in many of the works gathered in the book, and neither the tone of the introduction nor the organization of the study suggest obvious inroads to such an interpretive framework.(Within existing scholarship on Socialist Realism, one of the best examples of applying close looking and using this technique to discover the potential polysemy of Socialist Realist images is Ewa Franus’ “Frankenstein’s Bride: The Cntradictions of Gender and a Particular Socialist Realist Painting,” in Gender Check: A Reader, ed. Bojana Pejić (Köln: W. König, 2010), p. 71-78. Studies of socialist Eastern Europe that foreground material culture are often more likely to consider the openness or multiple meanings of socialist-era visuality and materiality; for example, see the essays collected in David Crowley and Susan E. Reid, eds., Style and Socialism: Modernity and Material Culture in Post-war Eastern Europe (New York: Berg, 2000).)

Neither evidence of a romanticized aesthetic rebellion against official art, nor of slavish adherence to official principles, the works in Socialist Realist Graphic Art in Albania reveal the complicated navigation between these two extremes. This is, perhaps, most evident in the drawings presented, where the tentative character and frequent incompleteness of the works resists a single, conclusive ideological message. The free and vigorous lines in Skënder Kamberi’s sketches, for example, give his figures an emotional charge that derives from our uncertainty about their thoughts and emotions. On the one hand, this uncertainty makes them seem ready to be filled in by the ideological goals of the Party, but at the same time it indexes the gap that remains between those ideological goals and the everyday experience of Kamberi’s individual subjects. This ambivalence is also present in many of the landscapes and cityscapes. In some images of villages, such as Bujar Zajmi’s engravings, the emphasis is undeniably on the transformation imposed on nature by the Party, evidenced by propagandistic signs and geoglyphs that serve to make the landscape literally readable, as well as by the traces of agricultural work. Elsewhere, however, in some of the works of Pandi Mele or Roland Karanxha, for example, the connection between workers and the landscape appears as an abundant condition that exceeds the Party’s reach. Of course, this is, in part, simply ideology masking itself behind an idyllic image of the freedom of rural life, but it also produces a space where different sources of meaning (individual village traditions, the aesthetic encounter with landscape) become available to viewers. Likewise, in cityscapes of Albania’s oldest cities, such as Berat and Gjirokastra, with their dense Ottoman architecture, the city’s Cubist forms present a picture plane lacking the clear hierarchal organization endemic to many Socialist Realist images. The same is true of Anastas Konstandini’s jumbled views of village streets, which likewise deny organization around a central, monumental structure. The point, again, is not that these images actively resist totalizing ideologies, but that their meanings exceed strictly utilitarian, propagandistic goals. Unfortunately, Velo himself never comments on the potential openness, or duality, present in many of the works gathered in the book, and neither the tone of the introduction nor the organization of the study suggest obvious inroads to such an interpretive framework.(Within existing scholarship on Socialist Realism, one of the best examples of applying close looking and using this technique to discover the potential polysemy of Socialist Realist images is Ewa Franus’ “Frankenstein’s Bride: The Cntradictions of Gender and a Particular Socialist Realist Painting,” in Gender Check: A Reader, ed. Bojana Pejić (Köln: W. König, 2010), p. 71-78. Studies of socialist Eastern Europe that foreground material culture are often more likely to consider the openness or multiple meanings of socialist-era visuality and materiality; for example, see the essays collected in David Crowley and Susan E. Reid, eds., Style and Socialism: Modernity and Material Culture in Post-war Eastern Europe (New York: Berg, 2000).)

It is just this potential openness, however, that seems most fruitful in light of reconsidering Socialist Realism—of the Albanian variety and, indeed, in its many other regional manifestations—in relation to narratives of twentieth-century art. At a time when contemporary art and cultural politics in Albania continue to grapple with defining and understanding the legacy of socialism as a cultural event, books like Velo’s are an important step towards understanding what Albanian Socialist Realism was and what about it still speaks to contemporary viewers. This understanding must involve a careful attempt to recover the motivations and uses of Socialist Realist images, particularly those that circulated in various contexts as the graphic arts did. Only when this recovery is undertaken can we fully appreciate what aspects of the images might have exceeded or complicated the rigorous structure so often attributed to Socialist Realism. Despite its significant flaws from a scholarly perspective, Socialist Realist Graphic Art in Albania should serve as a timely provocation to undertake the difficult work of recontextualizing the graphic arts produced by Socialist Realism, in Albania and elsewhere. One can either lament or celebrate that so much work remains to be done.

It is just this potential openness, however, that seems most fruitful in light of reconsidering Socialist Realism—of the Albanian variety and, indeed, in its many other regional manifestations—in relation to narratives of twentieth-century art. At a time when contemporary art and cultural politics in Albania continue to grapple with defining and understanding the legacy of socialism as a cultural event, books like Velo’s are an important step towards understanding what Albanian Socialist Realism was and what about it still speaks to contemporary viewers. This understanding must involve a careful attempt to recover the motivations and uses of Socialist Realist images, particularly those that circulated in various contexts as the graphic arts did. Only when this recovery is undertaken can we fully appreciate what aspects of the images might have exceeded or complicated the rigorous structure so often attributed to Socialist Realism. Despite its significant flaws from a scholarly perspective, Socialist Realist Graphic Art in Albania should serve as a timely provocation to undertake the difficult work of recontextualizing the graphic arts produced by Socialist Realism, in Albania and elsewhere. One can either lament or celebrate that so much work remains to be done.