Slow Life: Radical Practices of the Everyday

Slow Life: Radical Practices of the Everyday / Lassú Élet: Radikális Hétköznapok, Ludwig Museum, Budapest, April 9 – August 23, 2020

In the late 1930s, over a period of six years, Marcel Duchamp created twenty slightly varying miniaturized and portable galleries of sixty-nine of his pre-1935 works, enclosed in a suitcase and arranged to stand up like the displays of a travelling salesman. His Boîte-en-valise (1935-41) evoked the preparation of a man ready to be on the move at short notice; it anticipated, figuratively, the artist’s flight from occupied France to New York in 1942. Confronting the current pandemic crisis, which interrupted the planned April 2020 opening of the exhibition Slow Life: Radical Practices of the Everyday, the curators at Budapest’s Ludwig Museum (Petra Csizek, Jan Elantkowski, József Készman, Zsuzska Petró, Victória Popovics, and Krisztina Üveges) had to assemble an analogous sort of miniaturized exhibit. In this instance, however, their “microsite” exhibit was not designed for portability and travel, but for retreating to apartments and houses, and for immobilized sheltering as the pandemic runs its course.

To the Duchampian travelling art-salesman ringing doorbells and peddling his artistic wares, the Ludwig curators counterpoise, if not a startup e-commerce site, then at a minimum a social media forum replete with thumbnail images, video clips, sound files, and texts, as well as links to other media such as radio and television interviews and other websites. Forced to respond rapidly to the pandemic, the curators managed a partial realization in virtual form of two years of thought and preparatory labor that might otherwise have been lost altogether in the interminable series of cancellations we are experiencing today. We can truly be grateful for their quick work at the service of our experience of Slow Life. Beyond the instrumental value of the curators’ re-siting of the planned exhibition, however, the latter adds layers of meaning and experience to the exhibited works, which are resonant with questions of waste and recycling, damage and mitigation, appropriation and remediation in contemporary art and everyday life.

In their pathbreaking study Remediation, Jay David Bolter and Richard Grusin note that remediation operates through new media in three overlapping senses: by taking up previously mediated content within a new medium, with distinct technical capacities and limitations; by highlighting and commenting upon previous mediations and their relation to the current new medium; and finally by acting to repair, restore, or compensate for shortcomings in the previous mediations.(Jay David Bolter and Richard Grusin, Remediation: Understanding New Media (Cambridge, Massachusetts: The MIT Press, 1999), 52ff.) The Ludwig microsite is a remediated exhibit in each of these senses. It subsumes the multiple ontologies of gallery-sited objects—installations, photographs, videos, documents, artifacts, and curatorial texts—and remediates them through a pre-portaled web-world, wherein the gallery’s visitor-initiated interactions have been anticipated and programmed into hierarchically stacked pages of HTML code traversed by hyperlinks.

The microsite also marks its supplementary logic with respect to the cancelled analogue exhibition by yes, completing it on time, but by alternate, divergent means; by acknowledging its own imperfect representation of an exhibition that might have been or that has yet to come fully into being; and by providing a surfeit of expository and curatorial materials, especially textual, over what a live gallery exhibit would likely have allowed.(Several curatorial interviews underscore that the digital exhibition is not intended to substitute for the live exhibition, but rather to supplement its (temporary? indefinite?) absence or deferral. But the microsite does not only fall short of the planned exhibition, it also exceeds it. In an interview entitled “A Work of Art in the Age of Digital Publicity,” one of Slow Life’s curators, Józef Készman, expresses concerns about a potential for a loss of comprehensibility with the increase in the number of artworks that an individual may be able to experience digitally over that of live museum visitation. Készman also subtly teases out the difference between the planned Spring 2020 and an eventual later opening (still uncertain), in which the new context of reception, the aftermath of the pandemic shutdown, may reshape in not fully predictable ways the intended meanings of the exhibited artworks. At present, however, the microsite stands in the place of a still suspended decision, holding in play a number of virtual possibilities. See Műalkotás a digitalis nyilvánosság korszakában. Interjú Készman Józef Kurátorral, at https://ludwigmuseum.blog.hu/2020/04/09/mualkotas_a_digitalis_nyilvanossag_korszakaban.) Finally, as the curators note in their introduction, what I framed as remediation through the microsite is, for them, a means of compensating for the pandemic’s virtual yet no less effective damage to the artworks themselves, which were not able to appear in their original mediations: “We will do our best to compensate our visitors with an intensive online presence and provide detailed content about the background of the exhibition, the workflow, the artists involved in the project and the museum’s everyday life.”(http://slowlife.ludwigmuseum.hu/en/intro/.)

It is unlikely that the curators of Slow Life had Duchamp close to mind when they put together their exhibition, just as they could hardly have anticipated that a pandemic would force them out of gallery space and into a virtual boîte of webpages and critical discourse. There is, however, a connecting thread here that is more than just a critical fancy. We may discern a Duchampian vein in contemporary concerns with slowness, as heterochronic countercurrents to the accelerating flows and rhythms of global modernity. Duchamp, after all, nominated “delay” as a medium of art, designating his Large Glass “a delay in glass.” Although it was not their original intention, the pandemic compelled the Ludwig curators, too, to exhibit art in an interval of delay, the time between the planned opening and the still-hypothetical realization of that plan at a later date. As they write in their introduction: “The current situation also affects the preparation and implementation of the exhibition, as well as the opening event and the form of the planned programs. As soon as circumstances allow, the exhibition will be completed, but the opening scheduled for April 8 will be postponed.”(http://slowlife.ludwigmuseum.hu/en/intro/.) In addition, there are also dimensions of artistic process and the artist’s role at stake here.

Támas Kaszás. Contemplation X Never Work. Water color and pencil on paper, installed on a wood stick, 2007. Image courtesy of the Ludwig Múzeum.

With the Ludwig exhibit’s interest in slow ecological and environmental-scale processes in mind, we may recall Man Ray’s 1920 photograph Dust Breeding, showing Duchamp’s Large Glass with the accumulation of over a year of dust, to see that Duchamp brought his own “lazy,” “unemployed” subjectivity in languorous intercourse with non-human materiality as an alternative process of artistic (non-)making and remediated presentation; notably, he included a reproduction of Ray’s photograph in the Boîte-en-valise. Nor, as Maurizio Lazzarato makes evident in his essay Marcel Duchamp and the Refusal of Work(Maurizio Lazzarato, Marcel Duchamp and the Refusal of Work, trans. Joshua David Jordan (Los Angeles: Semiotext(e), 2014), is it accidental that not just Guy Debord but also Duchamp idles and wiles away the time behind the situationist slogan “Never work,” cited in an image on Tamás Kaszás’s artist profile.

Likewise, it is hardly difficult to imagine Duchamp’s approval of Endre Koronczi’s emphatic non-working in Extreme Sleep, a multichannel video loop encompassing fourteen years of experiments with “intentional sleeping” in various sites (see also his Extreme Sleep 2020, a forty-two minute video performance for the exhibition’s non/opening).

In other instances where slowness has been thematized in the arts, most notably in contemporary dance, but also in video and installation work by artists such as Bruce Nauman, Bill Viola, James Coleman, Tacita Dean, and James Turrell, the focus has been on vibratory intensities of the body or of ambient space and the training of attention on a range of microperceptions of difference within near-stillness or apparent repetition. The conception of the “slow” that the curators pursue in the current show, in contrast, is more overtly social and practical, even lifestyle-related in its orientation. As they state in their introduction, “The slow approach represents the need to rethink existing structures and reorganize established practices in the fields of society, economy, and everyday life alike. Its essence can be best expressed by consciousness and critical attitude, which bring forth more and more alternatives, from permaculture farming to zero-waste household, from voluntary simplicity to a concept of no-growth economy.”(http://slowlife.ludwigmuseum.hu/en/intro/.)

A key reference point, accordingly, is the slow food movement inspired by Carlo Petrini in the 1980s, marked too by the inclusion in the exhibit of Hungarian slow food exponent Gabó Bartha, whose extraordinary garden Terrapolis is inspired in name and concept by the work of the environmental feminist and science studies scholar Donna Haraway. This orientation is also reflected in the explicitly didactic portion of the microsite’s materials: “Slow Knowledge,” an A to Z lexicon of terms ranging from “alternative life strategies” to “zero waste,” with brief expositions of concepts and references to environmental and social-alternative thinkers including Paul Crutzen, Andreas Malm, Alf Hornborg, Carolyn Merchant, Jason W. Moore, Jem Bendell, Geir Berthelsen, Carl Honoré, and others.

Several of the works engage overtly with themes that align with this lexicon, for example, the photographs of Krisztina Erdei entitled Riseset, Victory of the Sun, which document her month-long retreat in the remote Turkish village of Çukurköy, where she participated in a community project to sustain the threatened village by taking on the herding of goats.

Krisztina Erdei. Riseset, Victory of the Sun. Photograph, 2009-2020. Image courtesy of the artist.

The work clearly resonates with such slow knowledge terms/concepts as “alternative life strategies” and “community thinking.” Similarly, Támas Kaszás’ thirteen-minute, captioned digital slideshow with sound, An Escapist Story (Forest School), with its narration of wandering in a forest and a progressive dissolution of the centered self into the entangled webs of diverse life, connects with entries such as “biodiversity,” “civil disobedience” (in reference to Henry David Thoreau), and “withdrawing, escapism.”

In their animated Punk Kitchen Fanzine—Pirate Edition, Syporca Whandal and Eszter Ágnes Szabó present pirate society as an alternative social organization to that of a capitalism focused on private property and a legal order designed to protect it, thus connecting with lexicon terms such as “anti-consumerism” and “criticism of capitalism.” These works are of course in no way merely illustrative of social and ecological concepts, but the curators have aligned their critical discourse closely with the artworks explicit thematic content and presented them together as a coherent conceptual index.

Petra Maitz. The Lady Musgrave Reef. Installation, 2002-today. Image courtesy of the Ludwig Múzeum.

Some works in the show are directly documentary in character, such as Ursula Biemann and Paolo Taveres’s thirty-eight minute video essay and multimedia installation Forest Law and Oliver Ressler’s six-channel video installation Everything’s Coming Together While Everything’s Falling Apart, which is represented on the microsite by the twelve-minute segment Ende Gelände, documenting an environmental protest occupation at the coal mines in the Lausitz region near Berlin. Analogous to these documentary depictions of community, but instead positioning art-making as itself the relational focus of community practice and collective action, Petra Maitz’s crocheted coral reef The Lady Musgrave Reef (an analogous parallel project, the L.A.-based Institute for Figuring’s Crochet Coral Reef is discussed at length in Donna Haraway’s recent book Staying with the Trouble: Making Kin in the Chluthucene) and Eszter Ágnes Szabó’s embroidered twelve-meter billboard embody shared voicings of the social and ecopolitical connotations of the works.

Judit Flóra Schuller’s offers a kind of verso-side consideration of the theme of community in her documentation of 128 solo walks in her work entitled Towards Nothingness (Walks). The walks constitute, she implies, an a-representational counterpart to the traumatic entanglements of her family archive, which is the focus of works of hers. At the other end of the rhetorical spectrum, but equally explicit in its exploration of solitary experience, Oto Hudec’s moving speculative video-fiction We Are the Garden, expounds experiences of personal loneliness, fragility, responsibility for others (both human and non-human), and hope in a post-apocalyptic landscape rendered nearly uninhabitable by climate change. As does, in its own way, the narrated solitude of the Thoreauvian (and at times Beckettian too) forest wanderer in Támas Kaszás’s An Escapist Story (Forest School), already mentioned above.

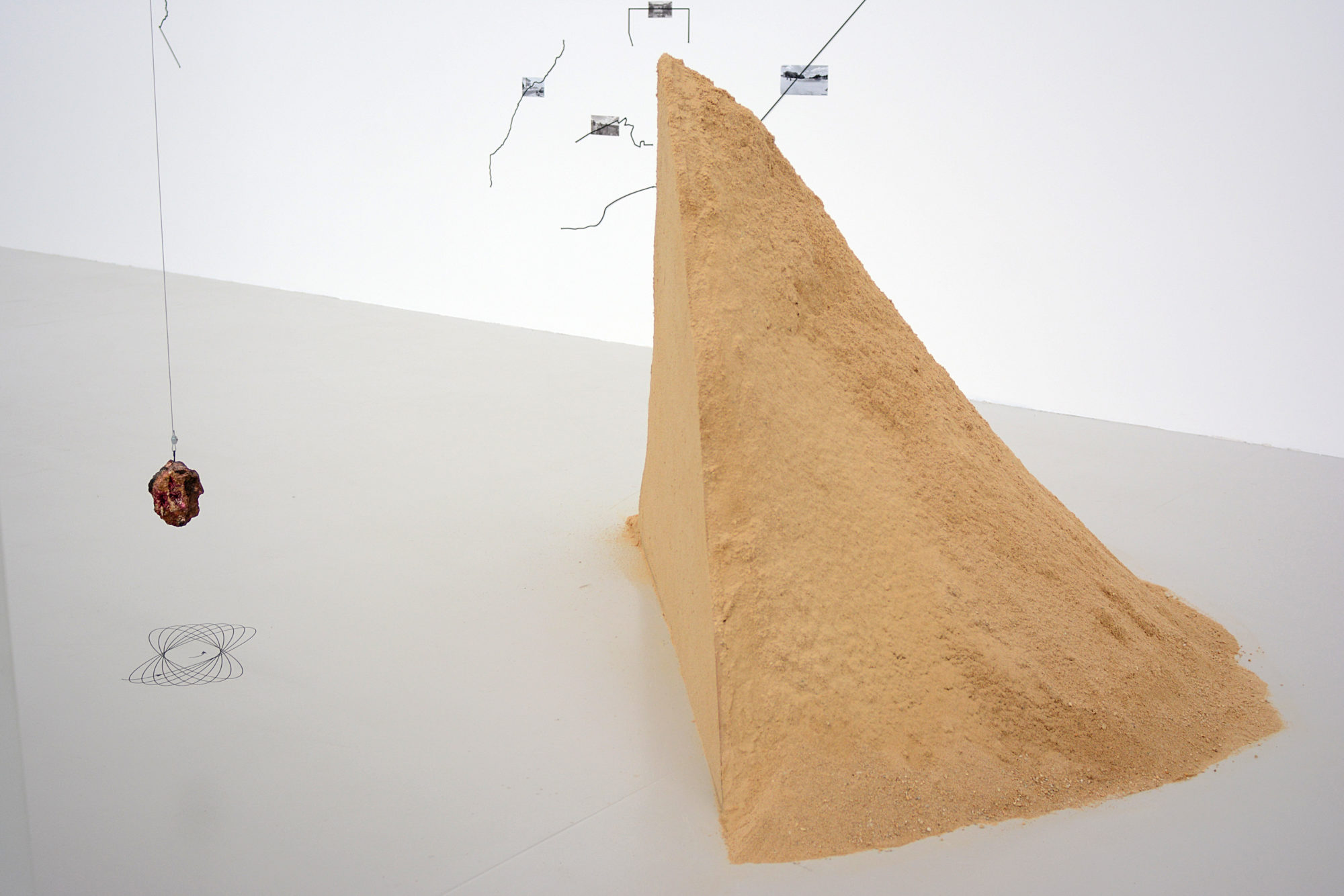

Anca Benera and Arnold Estefan. The Desert Rock That Feeds the World. Installation, 2019. Image courtesy of the Ludwig Múzeum.

Certain works in the exhibit map less easily onto the explicit didactics of the curatorial concept, because of their less overtly discursive and pedagogic character. In these works, the artists express thematic intentions more indirectly and immanently through the phenomenological experiences the works evoke—though such experiences are, at present, in turn accessible only in a mediated form, through the internet materials available on the microsite. These include the installations of Anca Benera and Arnold Estebán The Desert Rock That Feeds the World and The Driving Force of All Nature; Lois Weinberger’s Fallow Lands; the Pine Needle Carpet of Péter Mátyási; Rita Süveges’ painting Out of Control; Gideon Horváth’s infrared, long exposure photographs No Man’s Land; Manfred Erjautz’s untitled (at least on the microsite) installation. A notable instance is Anna Zilahi’s sound-installation The River Knows Better (Ophelia Lives), which explores the soundscape of the inner body, extending John Cage’s transformative experience of the rhythmic throb of his own blood circulation and the hum of his nervous system in a Harvard University anechoic chamber.

Támas Kaszás’s video Vandalizing an Aldo Leopold Bench might also be included here. Although it centers upon the gradual inscription of the phrase “time spent without work” on a wooden bench, the slow process of burning the phrase into the wood, the implication of painful torment as words form in a blackened script arising out of mute, flesh-like wood, as well as Kaszás’ self-reflexive use of a camera lens to focus the sun’s beam in a process of literal “light-writing” (photo-graphy), make this video an especially poignant poetic event that fans out richly beyond any manifest thematic content.(See http://slowlife.ludwigmuseum.hu/en/slow_motion/ on the exhibition site, and for the video: https://vimeo.com/420298992.)

Returning briefly to the Duchampian spirit with which I began, Emese Benczúr and Antal Lakner engage in revisionary ways with the poetics of the readymade, mobilizing the convergence of object and language to interrupt the flow of daily practice and arrest thought in the equivocal space of visual-verbal paradox. Benczúr’s Cut Before Use, a curtain-like set of vertical strips constructed from multilingual clothing tags that spell out in large letters the title phrase, suggests how the commodity fetish-object and commodified brand-language constitute an arrested phantasm of decentered, global flows of capital, labor, and money. The cut-out “bias” of the system, her title implies, is prior to any putative use-value that the clothing item might deliver. Lakner’s Dry Spa retools a Japanese wooden bath as a receptacle filled with dry cherry seeds. It evokes a future domesticity—utopian? dystopian?—that belies what we commonly consider to be the essence of bathing, namely the contact of the body with water. In a moment of arrested meaning—like a koan asking us to ponder “what is the feeling of a dry bath?”—Lakner invites us to reconsider our intimate, embodied relationship to water in our daily rituals of hygiene and, by extension, in so many areas of our daily life now under strain.

Microsite for the Exhibition: http://slowlife.ludwigmuseum.hu/en/.