Ricochets: Ukrainian Solidarity and Resilience at the 60th Biennale di Venezia

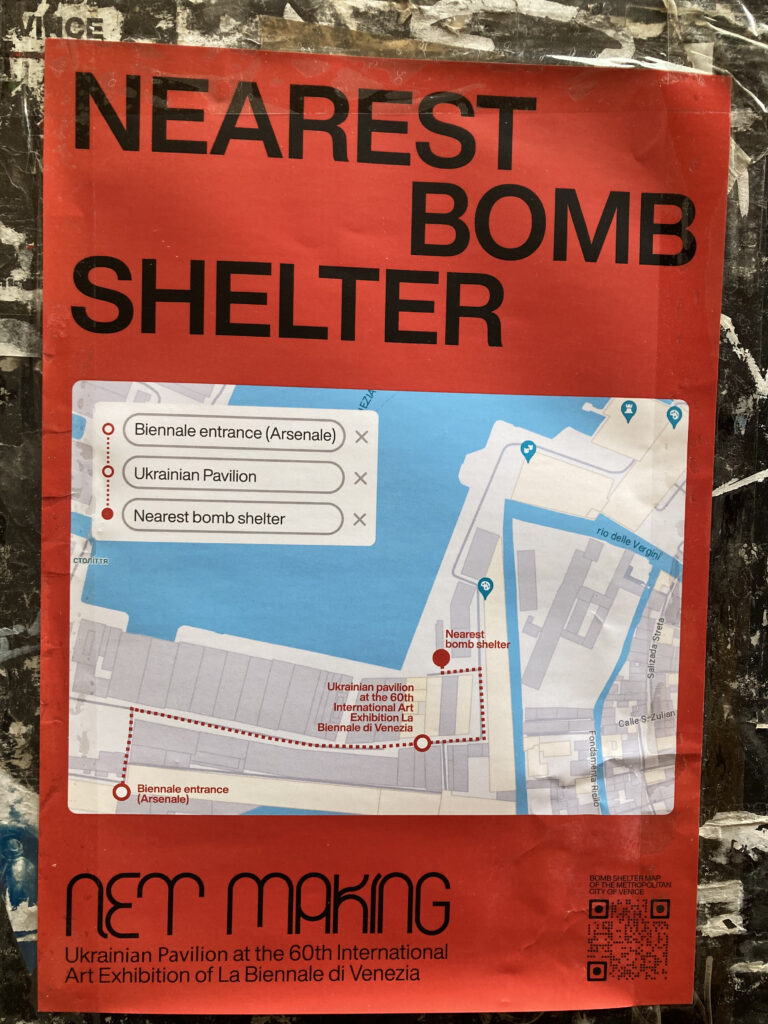

Posters for “Net Making”: Ukrainian Pavilion, Arsenale, Venice, 2024. Photograph by Klara Kemp-Welch.

The war in Ukraine continues to loom large at this edition of the Venice Biennale, as it did at the last, though now the nightmare unfolds in parallel with the heavily mediatized Israel-Hamas war. The city’s walls are plastered with red fly posters advertising directions to the “Nearest Bomb Shelter,” which, as a map shows, is located not far from the Ukrainian pavilion. This information vies for pedestrians’ attention with the “No Genocide Pavilion” Palestinian solidarity posters. An exhibition has been mounted in the Israeli pavilion, but a sign informs visitors that this will remain closed pending the release of hostages and a ceasefire agreement. Meanwhile, pro-Palestinian speakers attract crowds by the gates to main venues. Russia has made a point of not participating this year and has lent its unused pavilion to Bolivia. Reminders of war appear everywhere and provide the unofficial political frame for the Biennale. Its official rubric, Foreigners Everywhere / Stranieri Ovunque, borrowed for the occasion from Claire Fontaine’s series of neon signs by the Biennale’s curator, Adriano Pedrosa, director of the São Paulo Museum of Art (MASP) puts the politics of displacement and difference center stage. While complex histories of colonialism and human flow are thematized in many of the displays and national pavilions, my focus will be on those that relate explicitly to the War in Ukraine.

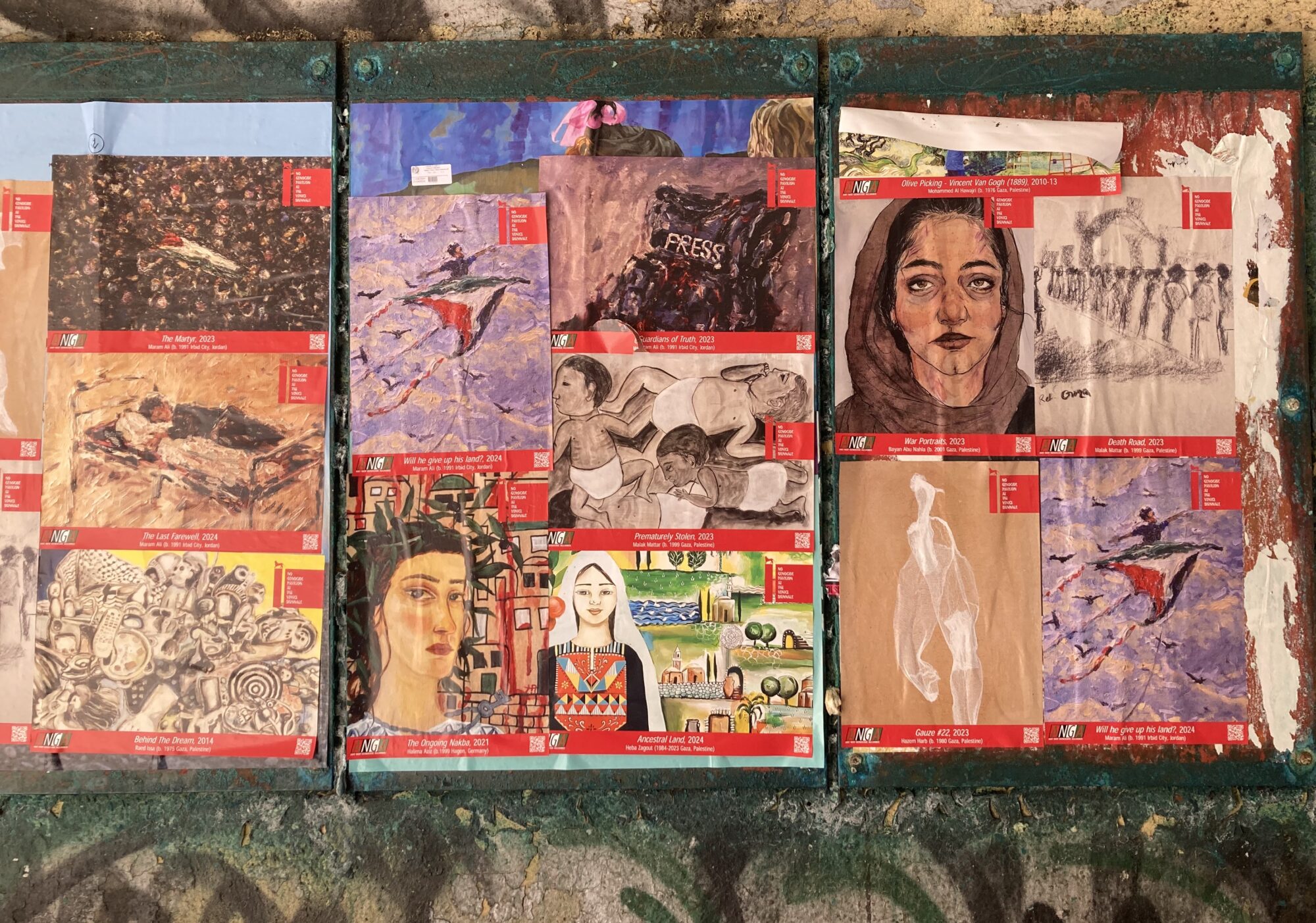

Posters for “No Genocide Pavilion,” Venice, 2024. Photograph by Klara Kemp-Welch.

Anna Jermolaewa represents Austria this year. The artist left the USSR in 1989 with her Ukrainian husband to seek political asylum, after suffering persecution due to their membership of the USSR’s first political opposition party, the Democratic Union. On entering the pavilion, we see assorted flower arrangements dotted around: each symbolizes a different revolutionary moment—the Rose Revolution in Georgia (2003), the Orange Revolution in Ukraine (2004), the Cornflower Revolution in Belarus (2006), the Tulip Revolution in yi2007), among others. The wall text explains that the installation (The Penultimate, 2017) is to serve as “a reminder of what undemocratic regimes fear most: an overthrow originating with the people.” These aides-mémoire are accompanied by strains of Tchaikovsky from the video of a Rehearsal for Swan Lake, 2004 (150 min.), in the room opposite, where Ukrainian dancer and choreographer Oksana Serheieva can be seen stretching at a bar. The artist explains that the piece refers to an old Soviet habit of looping the ballet on television during times of political upheaval, suggesting that the dancers rehearsing in her work are also rehearsing for political change in Russia today. In an adjacent room, an installation of Ribs (2022/24)—the name given to popular music illegally copied in the Soviet era onto X-ray film discarded by hospitals—serves as a reminder of longer histories of creative dissent.

Anna Jermolaewa. Untitled (Telephone Booths). Austrian Pavilion, Giardini, Venice, 2024. Photograph by Klara Kemp-Welch.

Jermolaewa’s personal experience as an asylum seeker is incorporated by way of a video re-enactment entitled Research for Sleeping Positions, 2006 (18 min). The artist shifts uncomfortably around on a bench at the Westbahnhof in Vienna, attempting to get some rest; “she has been here before, seventeen years earlier” when she “spent her first week on a bench in this station, sleeping on it every night before ending up in the refugee camp in Traiskirchen.” Nowadays, those wrestling with destitution in the urban environment face further impediments: “the bench now has armrests, installed as a deterrent.” A row of six metal Telecom Austria payphones, Untitled (Telephone Booths), 2024, some, but not all, out of order, have been taken directly from Traiskirchen refugee camp. One has a sign reading: “This telephone booth works. Feel free to call someone.” The booths have been used to make more international phone calls than any other phones in Austria. Making links between her historic flight from the Soviet Union and the fate of those fleeing war today, Jermolaeva has been involved in running a refugee-advocate organization since 2021, supporting Ukrainians displaced by war today.

The Polish pavilion is fully devoted to conveying the experiences of victims of the war in Ukraine. Here, the Open Group (for this project: Yuriy Biley, Wrocław and Berlin; Pavlo Kovach, Lviv; and Anton Varga, New York) show two films as part of the installation Repeat After Me. The first was recorded in a refugee camp outside Lviv in the months following Russia’s 2022 full-scale invasion and tells the stories of internally displaced people. The second is from 2024; the interviewees have left Ukraine and find themselves scattered around Europe and beyond. They each say their names and where they now live, before performing a haunting sound of war (a weapon, an air-raid siren), imitating the sound several times before asking the viewer to “repeat after me.” Curator Marta Czyż describes their selection as a “soundtrack of war,” and the strategy as responding in part to concerns about the weakness of images of war in today’s oversaturated mediascape. The sounds are accompanied by matter-of-fact information about the technical capacities of each type of weapon, provided in silent intertitles. Paradoxically, as Czyż notes, “the traumatic sounds featured in the 2024 film are simultaneously the sounds that actually saved the interviewees’ lives.”(Marta Czyż in Anna Theiss, People and Voices in Polish Pavilion at the 60th International Art Exhibition in Venice: Repeat After Me, exhibition leaflet/poster, 2024.) She hopes that the installation raises awareness of the experience of refugees more broadly to become “a collective portrait of refugee people all over the world,” pointing to how “‘refugee geography’ is as fluid as the geography of war,” and saying that the pavilion has the spirit of a “peace manifesto.”(Marta Czyż, “A Workshop on Empathy,” in Polish Pavilion at the 60th International Art Exhibition in Venice.)

Open Group. Repeat After Me. Polish Pavilion, Giardini, Venice, 2024. Photograph by Klara Kemp-Welch.

The installation courts participation, imitating a military bar, and providing microphones set up for Karaoke; the audience can take their turn at publicly enunciating the sonic experience of war, potentially striving for empathy. But while Czyż writes that the project “aims to jolt the viewers out of a state of apathy,” it also seems to test the limits of empathy. The faces of the participants in the 2024 film are muted and expressionless; their experience produces emotional distance. Pavlo Kovach reflected that in the two-year gap between the first and second film, somehow, “people have got used to war”; Anna Theiss calls this “normalization.” The project therefore examines the complex relationship between art, repetition, and catharsis, making it clear that mimesis, in and of itself, cannot result in psychological resolution.

The Ukrainian pavilion is devoted to “net making,” referring to one of the many forms of civilian support being coordinated since 2014, from raising funds to purchasing supplies for the armed forces. Given that targets for strikes are largely found by drone surveillance, effective visual camouflage is critical. Curators Viktoria Bavykina and Max Gorbatskyi recount how their exhibition title is inspired by the fact that “In many cities, strangers began to connect to weave camouflage nets… to disguise and protect equipment, weapons, engineering fortifications, and military locations.”(Net Making: Ukrainian Pavilion at the 60th International Art Exhibition of La Biennale di Venezia, exhibition leaflet, 2024, p. 1.) They explain that they took the idea of the net as their framing device because it is both “symbolic and, simultaneously, a very real embodiment of horizontal organization and collective action.” Nets symbolize the extent to which “Ukraine’s strength remains in its collective response of self-organization and mutual support. This applies to both the civil society and the military.” But making nets has also become “a group therapeutic practice that offers a sense of belonging.” The aim of the pavilion is to gather fragmented “experiences that are complex and controversial, requiring preservation and articulation…forging connections in times of crisis and attaining the strength to speak through unity with others.” The four projects include research-based and collaborative works spanning textiles, photography, and video. They all emphasize “joint work and co-creating.”(Viktoria Bavykina and Max Gorbatskyi, “About the Pavilion,” in Net Making, p. 1.) Andrii Dostiliev and Lia Dostilieva’s Comfort Work (2023–24) explores stereotypes of refugees, working with actors to play the roles of different variations of the category of the refugee deemed desirable by host countries. The work responds to the complexity of being forced into the role of refugee and having to navigate the myriad assumptions projected onto those seeking refuge. The work is important because it goes beyond statistics to pose challenging questions about how we view and treat those fleeing war, all the while rendering the identities and experiences of migrants opaque and affording them a degree of privacy that their life circumstances and their manner of mediatization conspire to erode.

Andrii Dostiliev and Lia Dostilieva. Comfort Work. Ukrainian Pavilion, Arsenale, Venice, 2024. Photograph by Klara Kemp-Welch.

The most powerful project in the Ukrainian display (arguably, in the Biennale as a whole) is Civilians. Invasion (2023) by Andrii Rachynskyi and Daniil Revkovskyi. The pair sourced material originating from eastern cities such as Mariupol for this film, editing together social media posts from Instagram, TikTok, and YouTube made by civilians at the time of the full-scale invasion. Their montage offers an account of how events were experienced on the ground: “it starts with the realization that a full-scale invasion has begun and attempts to understand how to survive it; continues with the risks experienced by civilians during hostilities, episodes of damage and destruction of housing; and ends with moments of some of the filmmakers dying, and what happens to the bodies of civilians after death,” including footage of the widespread “destruction of cemeteries as a result of hostilities.” The shocking ad-hoc footage includes scenes of people desperately trying to escape cities in cars with completely flat tires while being shot at by Russian forces, elderly people at home with frightened pets watching through their windows as neighboring blocks of flats are shelled and crumble, streets strewn with the bodies of dead civilians mown down by gunfire, and hungry dogs feeding on human remains. The soundtrack to these scenes consists largely of expletives, repeated against a backdrop of screaming and shelling.

Rachynskyi and Revkovskyi have made a distressing assemblage of the sorts of experiences that mainstream media do not represent. Besides conveying the unfathomably grim realities of the invasion for an audience that might not consider searching for such material online, the project “preserves important evidence from resources that are not permanent…videos can disappear any at any time: accounts may be blocked, and authors may delete the videos for security or other reasons. Collected in one archive, these videos will remain important eyewitness accounts of Russia’s armed aggression against Ukraine, war crimes, and the humanitarian crisis.”(Bavykina and Gorbatskyi, “About the Pavilion,” in Net Making, p. 6.) The artists’ observations echo Svitlana Biedarieva’s arguments about the “documentary turn in new Ukrainian art” when she claims that “for countries experiencing political and economic challenges, such as contemporary Ukraine, the mobility and visibility of documentary art becomes the principal instrument for the dissemination of information and the involvement of new audiences—not only in art but in the generation of knowledge about Ukraine’s identity.”(Svitlana Biedarieva, “The Documentary Turn in New Ukrainian Art,” in Contemporary Ukrainian and Baltic Art: Political and Social Perspectives 1991-2021, Svitlana Biedarieva ed., Ukrainian Voices, Vol. 14, (Stuttgart: Ibidem Verlag, 2021), p. 55.)

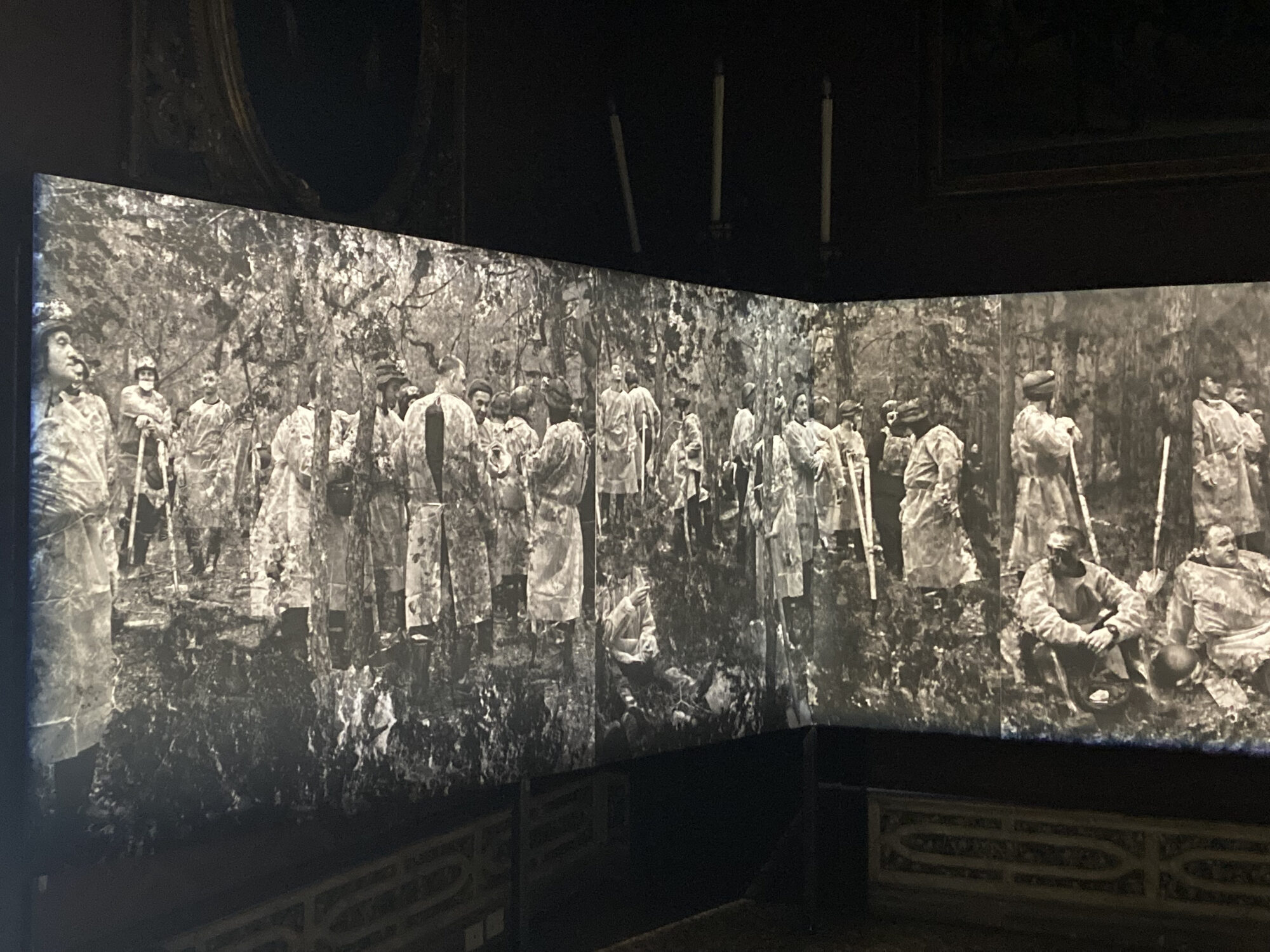

Yana Kononova. Izyum Forest, 2022. “From Ukraine: Dare to Dream,” Palazzo Contarini Polignac, Venice, 2024. Photograph by Klara Kemp-Welch.

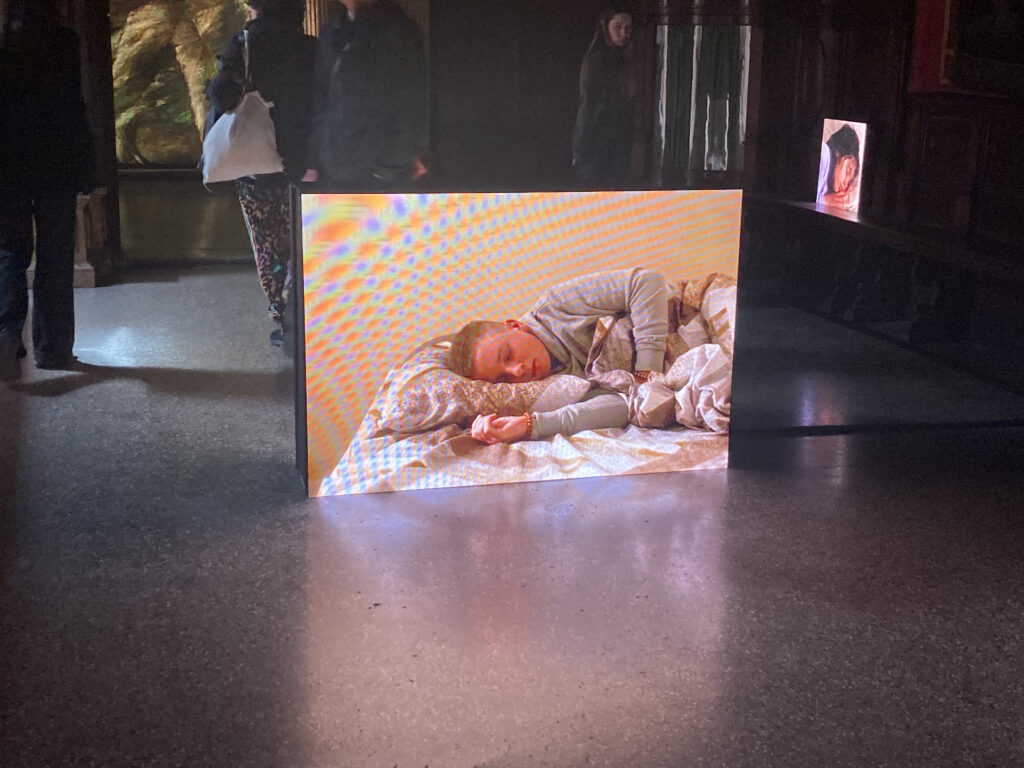

The war also dominates the large-scale collateral exhibition organized by the Victor Pinchuk Foundation and the PinchukArtCentre, From Ukraine: Dare to Dream. Yana Kononova’s Izyum Forest, 2022, is upstairs. This panoramic black-and-white photomontage surround shows stunned men with devastated expressions dressed in protective equipment while exhuming mass graves in eastern Ukraine. The intensely stylized patina renders the image disturbingly vivid. A label informs us that “most of the dead were civilians, many of whom showed signs of torture” and describes the work as “an emotional portrait of an exhausted nation and land.” Exhaustion resolves itself into sleep in Yarema Malashchuk and Roman Khimei’s moving six-channel video installation You Shouldn’t Have to See This (7’30” loop) which shows children of various ages, first abducted to Russia then returned to Ukraine, asleep in bed. We read that there have been anywhere between 20,000 and one million children taken to Russian territories by force since the invasion of 2014. Watching them being filmed is an awkward experience but provokes discomfort deliberately: by violating the “boundaries of privacy” the artists call war-time image-making into question, arguing that “every such image is primarily evidence of a crime, and only potentially a work of art (which should never have been created).”

Yarema Malashchuk and Roman Khimei. You Shouldn’t Have to See This. “From Ukraine: Dare to Dream,” Palazzo Contarini Polignac, Venice, 2024. Photograph by Klara Kemp-Welch.

These and many other artists’ projects currently on display at the 60th Venice Biennale showcase the resilience of Ukrainians fighting and suffering as a consequence of the Russian assault. The many gestures of creative solidarity adopt a wide range of approaches to the question of how contemporary art can respond to limit-cases of violence and devastation, shedding light on dimensions of wartime experience that go otherwise unrecorded. Such ricochets of the brutality of war contribute to the consolidation of a cultural consensus and play their part in fostering support for the Ukrainian cause.