“A Universal System for Depicting Everything”: A Dialogue Between Ilya Kabakov and Boris Groys

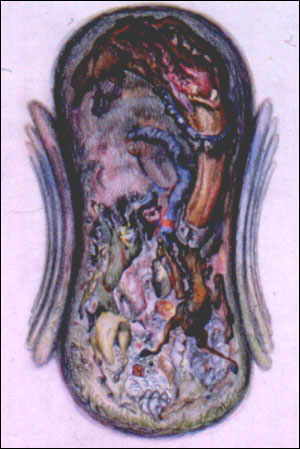

I. K.: Without any foreword my album “A Universal System for Depicting Everything” plunges into an exploration of some sort of fantastic system, namely, a system for a view from the fourth dimension. It is an elaboration, in several sketches, of how our reality, the different qualities of our reality, can be seen from this dimension. For the viewer, of course, what is being discussed is not at all comprehensible, nor is it clear who is the one proposing such a system, or who has seen it. The very flow of speech-emotional, not entirely logical, gasping-indicates that a rather strange subject is under discussion. The topic is not some abstract theory purely expressed in comprehensible scientific language. Under discussion, perhaps, is a strange kind of delirium that the viewer must elucidate over the course of the entire album, understand, even though many of the fragments are not entirely comprehensible. The question arises immediately: to whom does this delirium belong, who is the author of this album, what should be the attitude toward the one who drew this, or do we have here some sort of figure of estrangement.

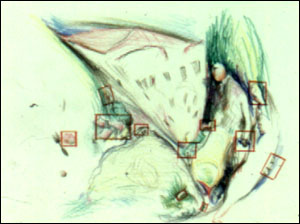

B. G.: In general this theme of the fourth dimension is very characteristic for the art of the avant-garde. The entire Russian avant-garde has been interpreted by many scholars as art of the fourth dimension. Works of Russian mystics of the beginning of the century-Gurdjieff, Blavatskaya, Uspensky-who wrote about the fourth dimension were used in these interpretations. There was a vast mystical tradition at the beginning of the century that in part has now been forgotten. Yet many people have interpreted Malevich, and Russian constructivism as a whole, as an art of the fourth dimension. But even given that, it seems to me that if you compare this interpretation to what can be seen in your album, then the artist-the author of this album-is demonstrating not some sort of new vision that was revealed to him in the fourth dimension as opposed to what he saw in the three dimensions in which we live. It seems to me that if you are talking about a universal system for describing everything, then that system might be a fourth dimension, and it might be a fifth dimension, and it might even be a twelfth dimension. And it seems to me that this impulse towards “describing everything” leads de facto to some sort of a miniaturized view. He whowished to understand everything is immediately lost in the details. This is my overall impression. The perspective recedes into the details. The more you strive to encompass everything, the more you are in fact dealing with tiny details, in the process losing “everything” from view, and losing whatever perspective you may have had. The greater the striving for an all-encompassing view, the greater the detail, the loss of the general.

I. K.: I would like to return again to the initial question I posed, mostly for myself. And herein rests in part the goal of our dialogue. It seems to me that you have to separate the author who created this album from the outside glance that observes him from the periphery, as it were from the fourth dimension. You are right to speak about the fact that all previous attempts to examine the fourth dimension were attempts to see what is going on in the fourth dimension. The whole idea of this character consists, on the contrary, in his attempt to see our three-dimensional world from the fourth dimension, to see what we ourselves look like from there. What there is in the fourth dimension, and what it looks like, this person doesn’t know, he doesn’t see any of that. His task is to exit into the fourth dimension in order to see our world from there. The rationale for his project lies, in all probability, in the fact that as he surveys the world he feels nothing but an enormous void. Our world, despite the fact that it is solid, appears to him to be absolutely tattered and not in any way reducible to a unified system. The systems of the Renaissance where perspectives of dimensions were established do not satisfy this person because his problem lies in the fact that, for example, I see you now but I don’t see the you that existed yesterday or what will happen to you tomorrow. The problem, it would seem, is absurd from the point of view of normative human logic. But from the point of view of this character there is an extreme deficiency in our vision. He proposes that there is a certain point of view that will remove this enormous deficiency of our localized eyesight. Let’s say I see before me a tape recorder, but I don’t know what happens to this tape recorder and this table if they are seen them from another point of view.

B. G.: If we ask what is the name of the personage you are talking about, I think the answer to the question is not hard to find, it is “God”. Divine vision is distinguished from human vision by the fact that it sees all moments in time simultaneously. It is not by coincidence that the fourth dimension is the temporal (space is three dimensions, the fourth is time). The problem posed by your album is the problem of divine consciousness or divine contemplation. You ask after the specific problems God encounters as he contemplates the world, viewing all moments in time simultaneously. The fact that God experiences these problems is widely known from theological literature. For example, he encounters significant problems saving souls or resurrecting a dead person. When God resurrects a person, the question arises at what moment should the dead person be resurrected. If the dead person is resurrected at the moment of death, the result will be an ugly, disintegrating corpse; if a little bit earlier, than the person is also old and ugly; if in youth, he is not the one that he is at a later time, etc. In other words, the theological question about the resurrection is entirely in sync with the logic of your album. Divine consciousness, as a result of the fact that it is located outside of time, sees all moments of time simultaneously. At the same time, it encounters specific difficulties that we as humans do not experience. The point being that any resort to the fourth dimension would probably result in more difficulties rather than relief. God has too many possibilities for choice, he faces too many details, too large a spectrum of potentialities, to a point where one has the impression that he cannot handle them all. It seems to me that your album is a description of the specific difficulties God faces as he contemplates reality. These difficulties do not arise for us since we see the world only as a cross-section, and hence as a whole. For us the problem of discerning all the details, or the correlation between these details and the whole, simply does not arise. God, on the other hand, does not see a cross-section. He sees all the moments in their sequence and winds up facing the necessity of a virtually impossible choice between various temporal stages. God thus finds himself inside a logical paradox from which we are saved by our mortality and by the limitations of our perspective. It seems to me that the internal mechanism of your album is the paradoxical nature of divine consciousness.

I. K.: All of that is perhaps so. Yet I am bothered by one small, insignificant number, the number four, which has been associated with such a universal and all-encompassing concept as God. We could exist in a one- dimensional or a two-dimensional world. Yet we have chosen a third variant, the three-dimensional world. Why not assume, then, that dimensionality is infinite, that there is a fifth, sixth, seventh dimension. Why not assume that there are certain beings, angels for example, who see our world from a fifth dimension? I am talking about measurability as an entirely new calculation of the world.

B. G.: I can tell you where I see the problem. Whether the measure we take is a fourth, a fifth, or a twentieth measure doesn’t really matter. The question is whether any of these dimensions are temporal. The point being that we can easily imagine to exist in the twelfth or in the twentieth dimension, but being mortal means that our existence is in any event finite. The hero of your album is immortal. He is immortal because he can outlive time. I call this “divine consciousness” because only God can move across any number of dimensions. The question is whether time is really a coordinate, a.k.a., something that has the potential of preempting all subsequent moments? The real rupture occurs when we talk about a consciousness that is capable of encompassing all the individual moments of time not in their succession but as a single dimension. Such a consciousness that can see all moments of time simultaneously is what I call “divine consciousness”. Divine consciousness is central in that it determines the relative difference between the human and the divine, between the mortal and the immortal, between the partial and the total. Therefore especially the artists of the Russian avant-garde (Khlebnikov who called himself the king of time; Malevich who sought to escape from the boundaries of time) strove to possess this divine vision. The artists of the 1960’s and 1970’s were also eager to acquire for themselves this divine vision. What I liked most of all in your album is the fact that it contains a sophisticated critique of this position. This critique does not simply consist of hinting at the impossibility of achieving such divine consciousness. The album rather sets up an experiment, a proposition or thesis according to which we assume that an artists actually has achieved divine consciousness. The question is: what next? As it turns out, the artist simply finds himself confronted with a new set of problems. His artistic vision begins to disintegrate into a heap of alternative details. Not only does he not acquire a view of everything, he completely loses whatever purview he might have had before acquiring divine consciousness. Now the artist only sees fragments and details that he cannot correlate with each other. That is to say that the problems implicit in divine vision turn out to be even bigger and even more difficult to resolve than the problems of ordinary human vision. It seems to me that this analysis suggests a more witty, more pessimistic and more radical critical perspective than the ordinary one that contends that even an artist is only human and therefore he cannot become God.

I. K.: As you know, ancient maps created at a time when the Earth had not yet been recognized as round represent the most fantastic combinations of continents. Certain continents appear overly large, while others appear shrunk. Certain areas were left white because they were as yet unexplored while others were, on the contrary, littered with innumerable details. From the point of view of today’s globe and today’s topographical maps, all this looks naive and ridiculous. But from the point of view of the topography of that time, these maps seem entirely reasonable. The artist in my album also uses the device of “another topography”. He proposes a systematic map in which each single point is connected to all the other points.

B. G.: But this topographical system consists of signs that are either too general or too particular. That is to say that the symbols used on the map are either too highly detailed or too generalized. In this way, the middle zone gets lost, the very zone where the illusion of identification is created. There are maps that are too detailed, making it impossible for us to find our bearings in them. And then there are maps that are too general, which means that once again they are of no use to us. The map you mention is just such a map; it is impossible to use it.

I. K.: I like your idea that we see the world either too generally or in excessive detail, with no middle ground in between. Looking at my album is like looking at a heavily crumpled shirt whose many protuberances are nothing but bubbles filled with emptiness. But then this is just how the album’s author thinks. One of the central ironic or reflective moments of the album is that, as you have pointed out, the map cannot be used. Even if we could enter the fourth dimension and see our world from that dimension, we still would not know what to do with your discovery. Incidentally, this is also what happened with many scientific discoveries-some of them brilliant, some not-where nobody has any idea what to do with them.

B. G.: There exists a “reality zone” in which we exist and which is characterized by the fact that we look at it with the naked eye. But there also exists an “armed” eye equipped with a telescope or a microscope. Through the telescope we can see different galaxies, we can describe what is going on there, but that does not mean that we can actually explore these places. Then there are the elementary particles, such as protons or neutrons. If I had an appropriately equipped eye I would see not “you” but instead a composite of very quickly rotating electrons, protons, and other particles. But this would not add anything to our conversation because this vision would remain dead “knowledge”. Itseems to me that the artist who drew your album has a “naked” eye. That is to say, even though he looks from the fourth dimension, he isn’t looking through a telescope or a microscope. The problem raised by the album, then, is the following question: What happens if we look with a “naked” eye at something that demands an “armed” eye?

I. K.: The “armed” eye looks at things that do not have any relationship to us. We are ourselves immersed in the banality of everyday reality. The author of the album decided to look literally at everything that we see around us. He doesn’t see anything new, in fact he sees nothing except for apples, a tramcar, a house. He sees exactly the same things that we see. The author is not after other worlds, flying surfaces, or a new reality. He is just as banal as any of us. He wanted to see a frying pan that is sitting on the table and then depict it. The point is that he believes that we see this frying pan incorrectly. Our world as we see it doesn’t satisfy him. He is inspired by the idea of finding the correct point of view for everything that exists. The theme of the album is the pathos of correctness. He sees this correctness in the fact that, having combined different time frames, he sees the frying pan, finally, from the correct position. There are moral positions, religious positions, and there is the position of everyday affairs. This person has the ambition to see correctly.

B. G.: In and of itself vision is not the same thing as what can be seen. When you try to show vision, this leads to a paradox. The demand for a new vision, a new sight, a new, altered view of things is the demand of any religious movement, any avant-garde. But this demand clashes with the necessity to show vision itself. In the very place where the demand to show vision arises it disintegrates because it is impossible to show vision. This impossibility is inscribed in your album. The author sees that he cannot show what he sees.

I. K.: Yes, but he still uses the device, a device that Malevich used in his squares and that Kandinsky used in his colored spots. By sheer willpower, in some sort of blindness, the author discovers a two-dimensional topographical map onto which he projects a fourth dimension. At the moment of transition from a system of a higher order to a system of a lower order, inevitable deformations and inevitable losses occur that distort communication. Each artist has his own topographical system. The author of the album argues that three-dimensional vision translated into two-dimensional representation has become outdated. On a two-dimensional surface, the author of my album depicts visions that he has acquired in the fourth dimension. Today we still use the maps and topography used by Leonardo da Vinci. His standards for translating three-dimensional space into a two-dimensional painting have been canonized.

B. G.: I think that the word dimension takes us astray because it creates the illusion of some sort of knowledge that can be conveyed to an other person. You can convey knowledge, but you cannot convey vision. At that very moment when you depict it for the viewer, when you illustrate it, you are already oriented toward the banal sight of the viewer.

I. K.: I look through his eyes.

B. G.: You look through his eyes. That’s why the problem rests with the fact that it is impossible to learn vision, it is impossible to convey vision, and it is impossible to encode it. All invocations to a new vision represent merely invocations. The viewer sees the products of your new vision with his old vision. The internal dynamics of your album are dictated by the tension that exists between the claim to a new vision on the part of the artist, and the demonstration of the old vision that he de facto uses, that he has to use since in it is founded the practice of drawing.

I. K.: There exists a form of intuition that allows people sufficiently close in consciousness to “see” the murky experience that another person is trying to signal, no matter how strange and vague these signals look from the point of view of a normal consciousness.

B. G.: I think this is so, although I would formulate it differently. I would say that the less a person is capable of such new visions, the more easily he can perceive them. There are such concepts as the inexpressible and the inarticulable.

I. K.: In art we do not in fact hear the inexpressible that a specific author or poet tries to reproduce for us. This stimulates and provokes the element of the unknown that is contained in each of us, the inexpressible that none of us can formulate. But given an encounter with such a formulation from another person, that vague resonance that we find in ourselves is awakened.

B. G.: It is often argued, incorrectly, that the artists of the avantgarde depicted the concealed, the inexpressible, or that which is not accessible to direct sight, meaning that they saw some sort of hidden reality and depicted it in the very same sense in which we see the reality that is given to us. It seems to me that what the avant-garde accomplished is something of an entirely different order. They did not so much unveil something that was hidden as they depicted the undepictable as undepictable. Just as the artists of the 19th century depicted a tree or a cow, the artists of the avant-garde learned to depict the undepictable. Malevich did this, Mondrian did this. When we see their works we understand that “this is the undepictable”, just as in a Realist painting we may understand that “this is a cow” These works can be understood only if you do not ask what the undepictable actually depicts. The same is true for your hero and the fourth dimension in general. The fourth dimension is that very thing that is inexpressible and undepictable. The author of your album has depicted it, but that doesn’t mean that he saw something that other people did not see.

I. K.: The matter is obviously somewhat murky but nonetheless the translation of the unknown, the “infection” of a person by the unknown element in another person occurs according to a specific combination of topographical maps or forms. There is apparently in us a combination of rhythms, a system of interrelationships between different elements, an instinct for what is concealed. This is why there is a specific set of combinations in the formal structure that the author proposes to us in his album.

B. G.: I agree with you, but it still seems to me that although this criterion exists, this criterion is not of a positive but rather of a negative nature. That is, it is not that the viewer recognizes the presence of the concealed through some sort of strong feeling. I think that something else occurs. I think that he does not recognize the ordinary.

I. K.: Correct.

B. G.: The majority of artists, no matter how hard they tried, could not eliminate familiar connections and combinations between things. In their works the viewer can always recognize some sort of familiar form, which means that he loses the sense for the inexpressible. Artists like Malevich and Kandinsky possessed unbelievable willpower and an extraordinary ability to avoid any combinations that might be familiar. Compare for example Malevich’s compositions with Lisitsky’s. The latter are all recognizable as constructions, something that is never the case with Malevich. The same can be said for the author of your album, he also has that feeling of the unknown.