Performing Oneself into History: Two Versions of Trio for Piano (Tallinn, 1969/1990)

During the late 1980s and early 1990s everything changed in the Estonian art world, as it did in the art worlds of other Baltic states and the entire Soviet Union. Not only was art itself – its techniques, media, strategies, contents, and purposes – rethought and the functional and financial system of the art scene reorganized, but also the self-perception of artists, their understanding of their activities and their relation to world culture, both contemporary and historical.

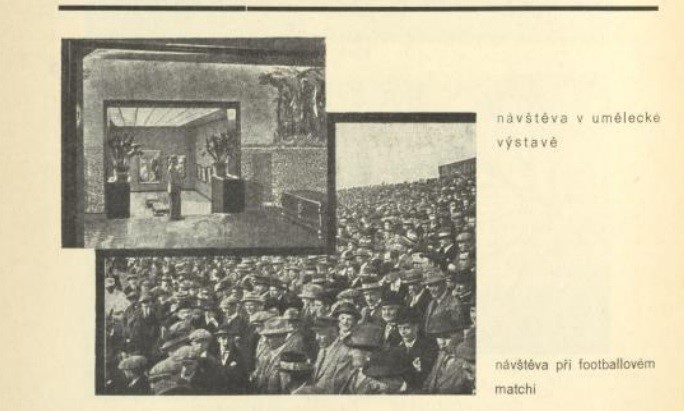

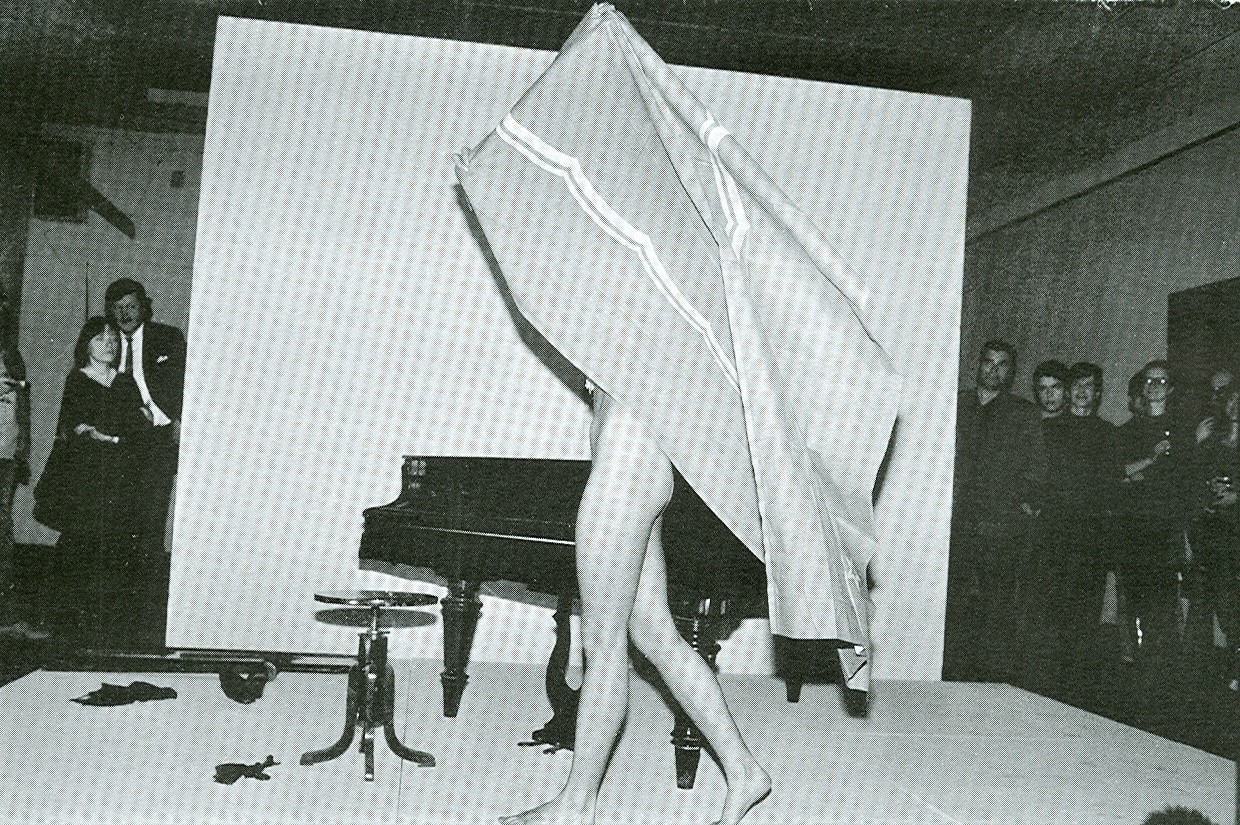

Leonhard Lapin, Ülevi Eljand, Ando Keskküla, “Trio for Piano,” 1990, happening in Tallinn Art Hall, 1990. Image courtesy of the Art Museum of Estonia, Tallinn.

Many artists, critics, and art historians have described the situation during this period as a time of total confusion. Much of what they had known about art, the ways they had thought and talked about art, no longer seemed adequate; there was too much new information and too little time to take it in.(Cf. Johannes Saar, “Competing landscapes: changing cultural horizons in the art writing of the 1980s” in: Sirje Helme, Andreas Trossek, Johannes Saar (eds.), Lost Eighties: Problems, Themes and Meanings in Estonian Art of the 1980s (Tallinn: Center for Contemporary Arts, 2010), pp. 23–38; Ants Juske, “The Myths and the Realities of Post-Communist Art” in: Sirje Helme, Johannes Saar (eds.), Nosy Nineties: Problems, Themes and Meanings in Estonian Art on 1990s (Tallinn: Center for Contemporary Arts, 2001, pp. 11–22.) The dialogue with the world outside brought a need for new narratives to contextualize Estonian art and its history.

Among other things, a new lens was used to view the recent history of art in Soviet Estonia. During the first half of the 1990s, several exhibitions focused on artistic movements and events that had been either partly or completely hidden during Soviet times, and which eventually defined the new version of Estonian post-war art history.(The first post-Soviet overview of Estonian art history was published in 1999: Sirje Helme, Jaak Kangilaski, Lühike eesti kunsti ajalugu (Tallinn: Kunst, 1999); a more profound examination (that still follows the narrative established during the 1990s) of Estonian art under the Soviet regime appeared in 2013–2016: Jaak Kangilaski (ed.), Eesti kunsti ajalugu 6 (1940–1991), vol. I, (Tallinn: Eesti Kunstiakadeemia, 2013), Jaak Kangiaski (ed.), Eesti kunsti ajalugu 6 (1940–1991), vol. II, (Tallinn: Eesti Kunstiakadeemia, 2016).) These movements and events were mainly related to Pop and Conceptual art. Exhibitions in the early 1990s revealed the activities of young artist groups of the 1960s such as ANK, SOUP, Visarid,(Exhibitions SOUP ’69–90 in Tallinn Art Hall in 1990, Eesti avangardi klassika in the gallery Luum (Tallinn) in 1992, Kollaaž eesti kunstis. 1960-ndad aastad in Tartu Art Museum in 1994, ANK ’64 in Tallinn Art Hall in 1995, 60-ndate kunst. Fenomeni rekonstruktsioon in the Art Museum of Estonia in 1996, Visarid in the gallery of Tallinn Art Hall in 1997.)and reconstructed experimental exhibitions from the 1970s (Harku ’75)(Harku 1975–1995 inTallinn City Gallery in 1995.) as well as the “bridge” that linked the Tallinn art scene to the Moscow underground.(Tallinn-Moskva 1956–1985 in Tallinn Art Hall in 1996–1997; see also Leonhard Lapin, Anu Liivak (eds.), Tallinn–Moskva 1956–1985, exhibition catalogue (Tallinn: Tallinn Art Hall, 1996).)

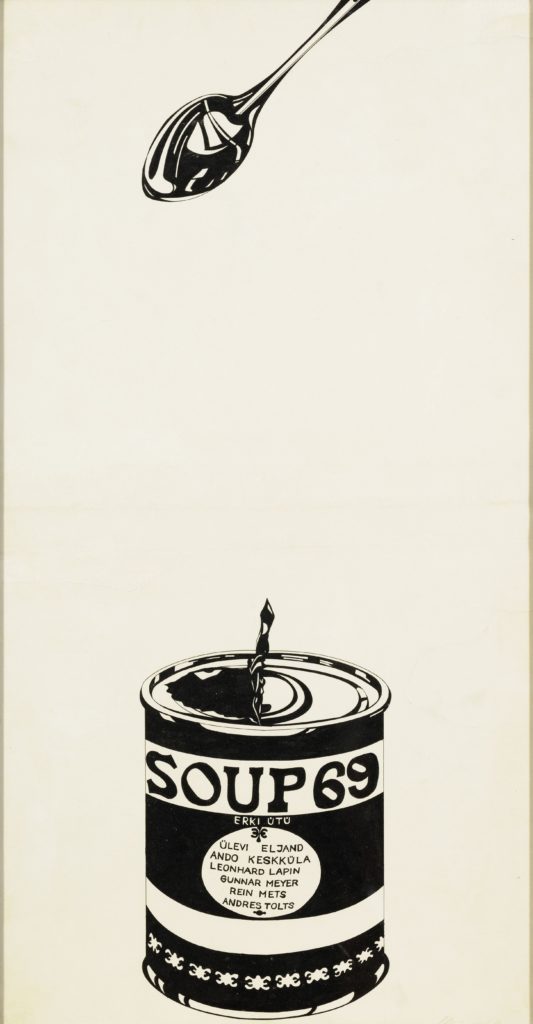

Leonhard Lapin, “SOUP’ 69,” 1969, poster, 61.2 x 32.3 cm. Image courtesy of the Art Museum of Estonia, Tallinn.

The first of the exhibitions that created a new narrative of the recent history of Estonian art was a show of the artist group SOUP at Tallinn Art Hall in 1990 (SOUP ’69–90). The group had been active in late 1960s, but never gained – or sought – broader attention. SOUP’s first exhibition took place in the Pegasus café in Tallinn in 1969, with a poster that referred to Andy Warhol’s Campbell’s Soup Cans (1962), after which the group was later named. The central figures of SOUP were industrial design students Ando Keskküla and Andres Tolts, and a student of architecture, Leonhard Lapin. Students of architecture Vilen Künnapu, Ülevi Eljand, Avo-Himm Looveer, Toomas Pakri, and others, were also involved in the group’s activities. SOUP initiated several activities that were later written into art history as examples of early Estonian performance art.

At the opening of the exhibition in the Art Hall a reenactment of the group’s happening Trio for Piano from 1969 – or rather a reinterpretation of this happening – was performed by the artists Lapin, Keskküla and Eljand. The fourth participant of the exhibition, Andres Tolts, did not take part in the reenactment as he was not actively involved in the initial event performed at the Estonian State Art Institute. Two other performers from 1969, architects Künnapu and Looveer, did not participate in the 1990 exhibition.

The aim of this article is to look at the dynamics and functions of this reenactment, its prehistory and afterlife, against the backdrop of the historical and cultural context of the late 1980s and early 1990s.I will first describe SOUP’s initial happening in 1969, then survey how performance art was introduced in Estonia through the articles written by SOUP member Lapin in the mid-1980s, and how it became more broadly visible through the activities of a younger generation of artists in the late 1980s. I will then analyze the reenactment performed in Tallinn Art Hall in 1990, describing how and why it was both similar and different from the initial event, while examining how it interacted with the Estonian art scene around 1990 and spawned a reevaluation of Estonian art history of the Soviet era.

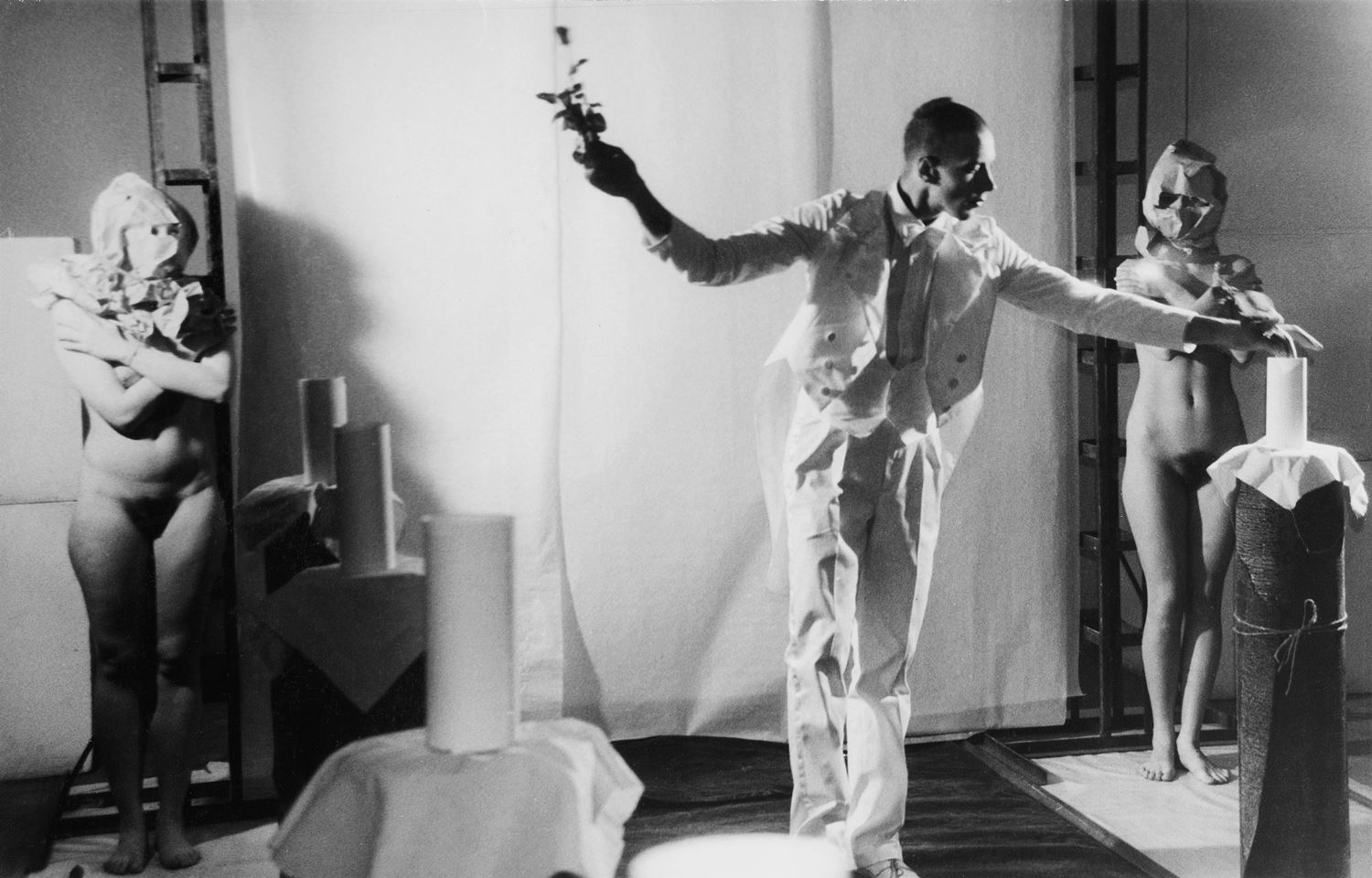

Toomas Pakri, Vilen Künnapu, Leonhard Lapin, “Papers in the Air,” 1969, happening on Pirita beach, Tallinn. Image courtesy of the archives of Leonhard Lapin.

It was stated in 1990, and restated later, that the artist group SOUP never really existed, at least not as a self-conscious and concrete circle of artists.(Cf. Sirje Helme, Popkunst Forever: Eesti popkunst 1960. ja 1970. aastate vahetusel / Estonian Pop Art at the Turn of the 1960s and 1970s (Tallinn: Art Museum of Estonia, 2010), p. 98 ff.) It was a loose group of students who studied together at the Estonian State Art Institute in Tallinn in the late 1960s and early 1970s (they mostly studied architecture or design), and organized different events and exhibitions on the peripheries of the art world. Their most significant contribution to Estonian art at thetime was the rethinking of the functions of artistic activity: they saw the artist as a conceptualizer rather than someone who virtuously produces objects and pictures (even if SOUP did this too, using different media and readymade materials), and performed interventions into the everyday environment.(Cf. Mari Laanemets, “Happening’id ja disain – visioon kunsti ja elu terviklikkusest” in Kunstiteaduslikke Uurimusi / Studies on Art and Architecture, 1–2 (19), 2010, pp. 7–34.)

One of the most well-known events organized by SOUP was the happening Trio for Piano, held on International Women’s Day on March 8, 1969, in the main hall of the State Art Institute. This event wasn’t called Trio for Piano initially (the name was given retrospectively by Lapin), nor was it – at least not unambiguously – understood as a “happening” at the time. There are no recordings of this event, only the memories of the participants and the audience, according to which this happening can be, cautiously, described as follows (keeping in mind that memories are rather fluid).

As the Art Institute had recently acquired a new piano, the old piano was donated to students who had requested it.(Video interview with the artist Leonhard Lapin at the travelling exhibition “Fluxus East: Fluxus-Netzwerke in Mittelosteuropa / Fluxus Networks in Central East Europe” (2007, curated by Petra Stegmann, produced by Künstlerhaus Bethanien). Recording in the archives of the Art Museum of Estonia: EKMa 12.1-8/27.) According to Lapin, they had heard that pianos were being destroyed by young and radical artists all over Europe.(Ibid.) The students were generally familiar with the phenomena of happenings and they had organized some similar events at the Art Institute and elsewhere.(The first one of these happenings (organised in cooperation with the students of Tallinn Conservatoire) took place on 1.12.1966 in the Secondary School no. 21 in Tallinn; a wave of happenings lasted from the late 1960s until the early 1970s.) International Women’s Day was celebrated all over the country with performances, lectures, and other events, and the art students made their own contribution to this celebration. In front of an audience of other students, they put the piano at the center of their activities and played on it and with it in every possible way. For example, Künnapu played the piano while reading an architectural drawing as a “score;” others painted smiling lips on the instrument and “made love” to the piano before moving it to one side and breaking it into small pieces, which were thrown to the audience to take away as souvenirs.(Video interview with the artist Leonhard Lapin.) During the event the artists also considered whether the piano should be thrown out of the window onto the street crossing next to the art school, which was known as a dangerous place where a lot of accidents happened; however in the end, this idea was abandoned.(Ibid.) The audience was excited and reacted to all of the activities energetically; the event was remembered many years later as a legendary disturbance, but it had no serious consequences for the organizers.(Ibid.)

The piano had a double role in this event. On the one hand, it was stated by the participants that they saw and perceived the piano – similarly to the organizers of happenings in other placesover the world – as a symbol of bourgeois culture and of elitist tradition that had to be attacked and destroyed.(Ibid.) On the other hand, they treated the piano as a woman – both because of the shape of the instrument, and the occasion of the event, Women’s Day – and handled it very carefully, even tenderly, before destroying it. It was probably the combination of the sexual connotations and the act of destruction (and the ambivalent meanings of this combination) that caused the audience to respond with such enthusiasm. It was later stated by Lapin that every kind of destruction felt “creative” in the turbulent late 1960s and under the circumstances of late Soviet society.(Leonhard Lapin, “Avangardi kuldsed kuuekümnendad” in: Leonhard Lapin, Avangard. Tartu Ülikooli filosoofiateaduskonna vabade kunstide professori Leonhard Lapini loengud 2001. aastal, (Tartu: Tartu Ülikooli Kirjastus, 2003), p. 193.) However, even if Trio for Piano was the only event by SOUP that included explicit erotic motives, several rather aggressive “plays” with female mannequins (used in the formal training of artists), reveal a certain pattern in the scenarios of the groups’ happenings – a pattern that leads to the destruction of a symbolic female figure. Of course, in the de-sexualized Soviet society every kind of (implicit or explicit) expression of sexuality was a radical act in itself. Still, one can’t overlook the fact that SOUP had only male members and the whole discourse of the neo-avant-garde in Estonia was dominated and defined by strong male leaders while only a few female artists established themselves as equals to them. Women were background figures, followers, and muses rather than active participants at these events.

The piano had a double role in this event. On the one hand, it was stated by the participants that they saw and perceived the piano – similarly to the organizers of happenings in other placesover the world – as a symbol of bourgeois culture and of elitist tradition that had to be attacked and destroyed.(Ibid.) On the other hand, they treated the piano as a woman – both because of the shape of the instrument, and the occasion of the event, Women’s Day – and handled it very carefully, even tenderly, before destroying it. It was probably the combination of the sexual connotations and the act of destruction (and the ambivalent meanings of this combination) that caused the audience to respond with such enthusiasm. It was later stated by Lapin that every kind of destruction felt “creative” in the turbulent late 1960s and under the circumstances of late Soviet society.(Leonhard Lapin, “Avangardi kuldsed kuuekümnendad” in: Leonhard Lapin, Avangard. Tartu Ülikooli filosoofiateaduskonna vabade kunstide professori Leonhard Lapini loengud 2001. aastal, (Tartu: Tartu Ülikooli Kirjastus, 2003), p. 193.) However, even if Trio for Piano was the only event by SOUP that included explicit erotic motives, several rather aggressive “plays” with female mannequins (used in the formal training of artists), reveal a certain pattern in the scenarios of the groups’ happenings – a pattern that leads to the destruction of a symbolic female figure. Of course, in the de-sexualized Soviet society every kind of (implicit or explicit) expression of sexuality was a radical act in itself. Still, one can’t overlook the fact that SOUP had only male members and the whole discourse of the neo-avant-garde in Estonia was dominated and defined by strong male leaders while only a few female artists established themselves as equals to them. Women were background figures, followers, and muses rather than active participants at these events.

Trio for Piano is considered to be one of the exemplary events in the early history of happenings in Soviet Estonia, as it related to both the world culture of the time and to the specific context where it occurred. However, this event was not only an activity that can be described as a “happening” in an art historical context; it was equally – or even more so – a product of the ambiguous social atmosphere of the late 1960s that had created specific ways of relating to the environment, especially among students and within youth culture more generally. The State Art Institute was one of the few places that provided a slightly more liberal space for experimenting with art and behavioral norms, along with the summer camps hosted by the magazine Noorus (Youth) and the café of Tartu University. The art students later said that they were often “living within the happening” (or “living as a happening”).(Interview with Leonhard Lapin by Mari Laanemets, March 2003 (transcription), Interview with Vilen Künnapu by Krista Kodres in: Maja 3, 2001, pp. 55–56.) They looked and found impulses in everyday life that allowed them to create small performances, to intensify the absurdity of life, sometimes to shock the “Soviet bourgeoisie” on the streets. Moreover, it was not only art students who lived this way, but also many other young people too – especially those who belonged to the cultural intelligentsia or to hippie communities and other subcultural groups. There is some documentation of similar events that took place outside of the art world and probably dozens, maybe hundreds, of forgotten performances. These performances were not reflected in any writings about art or society at this time, even though theword “happening”was sometimes usedby theater critics (to refer to the experimental theater of the 1960s); it also occurred in one published text by Lapin, who first described happenings as social activities (along with the discussions, sport games and parties that took place in the summer camp organized by Noorus), not artistic ones.(Leonhard Lapin, “Metsa ääres, mere veeres … Nooruse IV laager 1969” in Noorus 8, 1969, p. 53.)

These performances were not reflected in any writings about art or society at this time, even though theword “happening”was sometimes usedby theater critics (to refer to the experimental theater of the 1960s); it also occurred in one published text by Lapin, who first described happenings as social activities (along with the discussions, sport games and parties that took place in the summer camp organized by Noorus), not artistic ones.(Leonhard Lapin, “Metsa ääres, mere veeres … Nooruse IV laager 1969” in Noorus 8, 1969, p. 53.)

In 1986, at the time of perestroika (when hidden parts of the art life in the Soviet Union were gradually revealed), Lapin first introduced the activities of the student group he called SOUP in the art magazine Kunst (Art); among other things, he described the “happenings” they created back in the 1960s.(Leonhard Lapin, “Startinud kuuekümnendatel. Mälestusi ja mõtteid” in Kunst 1, 1986, pp. 16–23.) This article was followed by Lapin’s more structured overview of early Estonian performance art in the magazine Teater. Muusika. Kino (Theater. Music. Cinema) the following year.(Leonhard Lapin, “Mängides happening’i” in: Teater. Muusika. Kino 5, 1987, pp. 78–91.) Here, Lapin not only wrote about SOUP, but also mentioned other similar activities, most importantly those organized by young musicians (Arvo Pärt, Kuldar Sink, Toomas Velmet) in the late 1960s. Both texts presented a survey of Western performance art from the Futurists to the 1960s, then turned to the Estonian happenings that were described according to the unpublished article “Happening in Estonia,” Lapin had allegedly written in 1970.(This text has been published in: Leonhard Lapin, Valimik artikleid ja ettekandeid kunstist. 1967–1977, Tallinn: author’s publication, 1977; see also Leonhard Lapin, “Avangardi kuldsed kuuekümnendad”, pp. 193.)

One of the most cited and possibly most significant parts of this text deals with the term “happening”:

One of the most cited and possibly most significant parts of this text deals with the term “happening”:

“In our mother tongue, the unpleasant-sounding ‘happening’ […] could be replaced simply with the word ‘play’ [in Estonian ‘mäng’]. Yes, this is the play typical of small girls and boys. Take a number of unimportant things, functionless objects, insignificant events and circumstances, a little air, sun, water, everyday voices and festive sounds and create a new fantastic world where powerless parts of reality are turned into effective, growing power that shows the values of the real world as trivial, opening up their absurdity. The artists are like children playing themselves out of this reality – so dangerous for illusionists and mystifiers – and living a high-valued, unreal life…”(Quoted from: Leonhard Lapin, “Avangardi kuldsed kuuekümnendad,” p. 193.)

Lapin constantly projected the events created by art students and young musicians in Soviet Estonia of the 1960s onto the history of Western performance art and, not always quite adequately, asserted their cohesiveness. He also wanted, as stated in the quotation above, to “purify” the phenomenon of the happening, to find an archetype (i.e. play) for the events he and his friends had initiated in the 1960s, and to distance these events from similar activities made elsewhere in the world. The most coherent idea behind this construction is the assumption that Estonian happenings were independent on the practical level, but were related to world culture on a certain “spiritual” level. In other words, artists in Soviet Estonia did the same things as artists in the Western world (or elsewhere) not because they wanted to imitate them, but because they intuitively (and despite of the isolation of a totalitarian state) knew as much as artists in the free world.

Around the time Lapin wrote these texts that became the basis for the early history of performance art in Estonia, the first public performances were made in Tallinn by a younger generation of artists, which included Siim-Tanel Annus, Jaak Arro, Raoul Kurvitz and Rühm T. Later, in 1989 and 1990, the first exhibition of Estonian art organized by Western curators, Structure/Metaphysics, travelled to Finland, Sweden and Germany, presenting both constructive and symbolist tendencies in Estonian art of the twentieth century.(Cf. Marketta Seppälä (ed.), Struktuur/Metafüüsika. Vaatenurk eesti nüüdiskunsti / Struktuuri/Metafysiikka. Näkökulma virolaiseen nykytaiteeseen / Struktur/Metaphysik. Perspektiven der estnischen Gegenwartskunst, Pori: Porin Taidemuseo, 1989.) Following their performances at the openings of Structure/Metaphysics and elsewhere in the Nordic countries, Kurvitz and Annus suddenly became well-known performance artists – Annus was assigned the position of the performance king of Estonia in the Scandinavian media.(Vappu Vabar, “Siim-Tanel Annus” in: Johannes Saar (ed.), Eesti kunstnikud I (Tallinn: Soros Center for Contemporary Arts, 1998), p. 11.) Surprisingly (or perhaps not) it turned out that performance art was often much more easily understood and more exciting for Western audiences than the art that was considered important in Estonia. In his performances, Annus usually appeared as a king dressed in white carrying out ritual-like activities; Kurvitz took the role of a decadent dandy assisted by naked girls while creating situations that were elegant, slightly shocking and sometimes brought the artist to the border of physical danger. The highly symbolic, sublime, and decadent activities by Annus and Kurvitz allowed them to represent both the suspenseful political atmosphere of the late 1980s and the wild energy that was expected to burst out from the liberated cultural world of the Soviet Union.

Around the time Lapin wrote these texts that became the basis for the early history of performance art in Estonia, the first public performances were made in Tallinn by a younger generation of artists, which included Siim-Tanel Annus, Jaak Arro, Raoul Kurvitz and Rühm T. Later, in 1989 and 1990, the first exhibition of Estonian art organized by Western curators, Structure/Metaphysics, travelled to Finland, Sweden and Germany, presenting both constructive and symbolist tendencies in Estonian art of the twentieth century.(Cf. Marketta Seppälä (ed.), Struktuur/Metafüüsika. Vaatenurk eesti nüüdiskunsti / Struktuuri/Metafysiikka. Näkökulma virolaiseen nykytaiteeseen / Struktur/Metaphysik. Perspektiven der estnischen Gegenwartskunst, Pori: Porin Taidemuseo, 1989.) Following their performances at the openings of Structure/Metaphysics and elsewhere in the Nordic countries, Kurvitz and Annus suddenly became well-known performance artists – Annus was assigned the position of the performance king of Estonia in the Scandinavian media.(Vappu Vabar, “Siim-Tanel Annus” in: Johannes Saar (ed.), Eesti kunstnikud I (Tallinn: Soros Center for Contemporary Arts, 1998), p. 11.) Surprisingly (or perhaps not) it turned out that performance art was often much more easily understood and more exciting for Western audiences than the art that was considered important in Estonia. In his performances, Annus usually appeared as a king dressed in white carrying out ritual-like activities; Kurvitz took the role of a decadent dandy assisted by naked girls while creating situations that were elegant, slightly shocking and sometimes brought the artist to the border of physical danger. The highly symbolic, sublime, and decadent activities by Annus and Kurvitz allowed them to represent both the suspenseful political atmosphere of the late 1980s and the wild energy that was expected to burst out from the liberated cultural world of the Soviet Union.

On this background, one can assume that SOUP’s reenactment of Trio for Piano was inspired both by the wish to revisit the group’s past and by contemporary developments on the Estonian art scene. During the opening of the SOUP’s retrospective at Tallinn Art Hall, the basic scenario of Trio for Piano was the same as in 1969: three men played on and with the piano before destroying it. However, there were also some notable changes. First, the three men were not young students any more, but established artists in their forties wearing suits and presenting themselves as classics of the hidden Soviet avant-garde. Secondly, in addition to the initial sexual connotations (making love with the piano), a stripper carrying the flag of the Estonian SSR was brought onto the stage during the happening. (Similarly to performance art, striptease was a newly discovered phenomenon in Estonia during the late 1980s and early 1990s; some of the strippers became media stars and striptease performances were held on every possible occasion.) According to Lapin, theself-ironical approach that revealed changes both in the environment and in the artists’ positions (in comparison with 1969) was intentional, especially as the retrospective was first planned for 1989 and the reenactment was supposed to take place on the twentieth anniversary of the initial event.(Conversation with the artist Leonhard Lapin on 22 May, 2017.)

On this background, one can assume that SOUP’s reenactment of Trio for Piano was inspired both by the wish to revisit the group’s past and by contemporary developments on the Estonian art scene. During the opening of the SOUP’s retrospective at Tallinn Art Hall, the basic scenario of Trio for Piano was the same as in 1969: three men played on and with the piano before destroying it. However, there were also some notable changes. First, the three men were not young students any more, but established artists in their forties wearing suits and presenting themselves as classics of the hidden Soviet avant-garde. Secondly, in addition to the initial sexual connotations (making love with the piano), a stripper carrying the flag of the Estonian SSR was brought onto the stage during the happening. (Similarly to performance art, striptease was a newly discovered phenomenon in Estonia during the late 1980s and early 1990s; some of the strippers became media stars and striptease performances were held on every possible occasion.) According to Lapin, theself-ironical approach that revealed changes both in the environment and in the artists’ positions (in comparison with 1969) was intentional, especially as the retrospective was first planned for 1989 and the reenactment was supposed to take place on the twentieth anniversary of the initial event.(Conversation with the artist Leonhard Lapin on 22 May, 2017.)  The cautious sexual connotations of the happening in 1969 were replaced by the most explicit ones (engaging a stripper) to emphasize the sudden transition from de-sexualized Soviet society to the over-sexualized post-Soviet world. Additionally, the now well-known performances by Kurvitz and Rühm T presumably influenced SOUP’s decision to involve a naked woman.

The cautious sexual connotations of the happening in 1969 were replaced by the most explicit ones (engaging a stripper) to emphasize the sudden transition from de-sexualized Soviet society to the over-sexualized post-Soviet world. Additionally, the now well-known performances by Kurvitz and Rühm T presumably influenced SOUP’s decision to involve a naked woman.

There are some photographs of the 1990 reenactment at Art Hall, but it is still difficult to describe the actual event and its atmosphere adequately, so I am once again dependent on the memories of the participants and of the viewers. It has been said that the atmosphere of the event was frantic and nostalgic,(Eha Komissarov, “SOUP ’69 – kakskümmend aastat hiljem” in: Kunst 1, 1992, p. 17.) but also that the happening was mainly a parody carried out by the artists, without real interest or engagement, an ironic presentation of a protest from the past.(Sirje Helme, “Ah, Andy!” in Reede, 23.02.1990, p. 8.) As for the audience, the stripper definitely got more attention and was more exciting than the destruction of the piano. The art critic Sirje Helme, who has followed SOUP since the late 1960s, wrote after the opening of their retrospective that the group was mainly characterized by action: by doing something, by showing, by acting out (and less by creating self-contained pictures and objects).(Ibid.) Helme suggests that maybe one day the reenactment of Trio for Piano would be seen as the funeral of Estonian avant-garde: a destroyed piano in the 1960s was a symbol of an outdated cultural model, but in the 1990s it had become a symbol of another tradition (the avant-garde) that belonged to the past and had to be dismissed.(Ibid. Estonian art world of the late 1980s and early 1990s was very much engaged with the discussions on “trans-avant-gardes.” Ando Keskküla, Eha Komissarov,”Avangardi idee jälgedes” in Kunst 2, 1989, p. 16.)

The opening of the SOUP retrospective in 1990 has not, in fact, become known as the funeral of the Estonian avant-garde, but the photographs of the reenactment have been often reproduced, less to document Estonian art in the early 1990s than to reconstruct what happened in the late 1960s. Thus these photographs serve as a certain window into two different pasts: that of the 1960s and the 1990s.

The opening of the SOUP retrospective in 1990 has not, in fact, become known as the funeral of the Estonian avant-garde, but the photographs of the reenactment have been often reproduced, less to document Estonian art in the early 1990s than to reconstruct what happened in the late 1960s. Thus these photographs serve as a certain window into two different pasts: that of the 1960s and the 1990s.

The reenactment of Trio for Piano in 1990 served as a tool for the artists of SOUP to look back at their own history. The fact that the event from 1969 was repeated shows that it was considered to be something significant; the fact that the event was turned into a parody also shows a certain skepticism towards it. My assumption is that this reenactment reflects the ambivalence and uncertainty in rethinking the models that determined the cultural self-perception of artists in Estonia during and after the fall of the Soviet Union. However, this uncertainty shouldn’t be seen as something that had to be overcome, but rather as a state of mind or form of action that had a productive rather than subversive potential. Furthermore, this ambivalence and uncertainty characterized not only the reenactment of the happening, but also the initial event in 1969. The significance of this event in the late 1960s was not only due to the fact that it was similar to other events elsewhere or that it was unique to specific circumstances, but rather due to its playful handling of different contextual determinations, of different levels and sources of knowledge and imagination. When this event was repeated and interpreted in 1990, not only were the movements and gestures of the initial event revived, but, more importantly, the “inbetweenness” of a certain cultural moment in history was restored.

This article is part of the Special Issue on Reenactment in Eastern Europe. Articles in the issue include:

[su_menu name=”Reenactment”]

Anu Allas is an art historian and a curator in the Kumu Art Museum in Tallinn, Estonia. Her main research interests include post-war art in socialist Eastern Europe and neo-avant-garde artistic practices from late 1950s onwards. She received her PhD from Free University Berlin in 2013 for a dissertation on experimental practices in Estonian art and theater of the 1960s. She has published articles on Estonian and Eastern European art of the socialist era and on contemporary art, and has curated exhibitions on post-war art, among others, the permanent exhibition Conflicts and Adaptations: Estonian Art of the Soviet Era (1940–1991) at the Kumu Art Museum in 2016.

Anu Allas is an art historian and a curator in the Kumu Art Museum in Tallinn, Estonia. Her main research interests include post-war art in socialist Eastern Europe and neo-avant-garde artistic practices from late 1950s onwards. She received her PhD from Free University Berlin in 2013 for a dissertation on experimental practices in Estonian art and theater of the 1960s. She has published articles on Estonian and Eastern European art of the socialist era and on contemporary art, and has curated exhibitions on post-war art, among others, the permanent exhibition Conflicts and Adaptations: Estonian Art of the Soviet Era (1940–1991) at the Kumu Art Museum in 2016.