One on One Series: Kristina Benjocki, Ground Bindings (Nada, Gizela, Tereza) (2019)

The One on One series presents timely encounters between ARTMargins Online editors and contemporary artists, focused on one work.

Sven Spieker: Ground Bindings – could you comment on how this project came about, and also about its title?

Kristina Benjocki. Ground Bindings (Nada, Gizela, Tereza), 2019. Installation view at TENT gallery, Rotterdam. Photograph by Add Hoogendoorn. Image courtesy of the artist

Kristina Benjocki: Ground Bindings (Nada, Gizela, Tereza) is an installation with three handwoven textiles, 90×120 cm each, wallpaper, glass shelf and yarn labels. The work explores haptic memory and proposes understanding touch as an intimate way of bearing witness to personal and collective histories. The three textiles at the heart of the installation are handwoven, using the three basic binding systems. The phrase “ground binding” is a translation from the German word “Grundbindungen.” The term is used in weaving and it stands for the three basic binding systems: tabby, twill, and satin.

SS: Your project began with three skeins of wool you found at your mother’s house. All three were produced in different factories located in three former Yugoslav republics (Serbia, Croatia, Macedonia). How important is the memory and legacy of ex-Yugoslavia for your project?

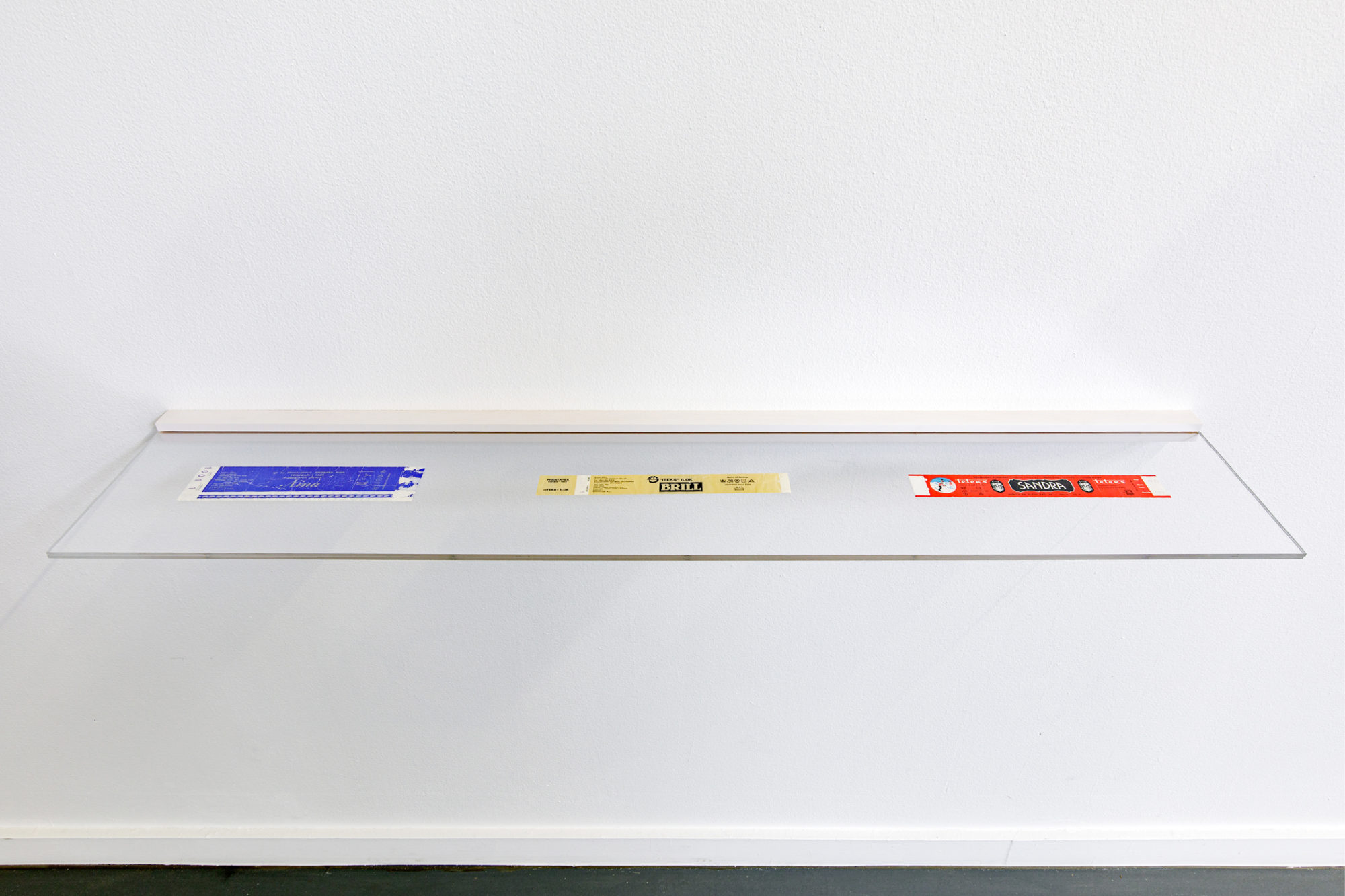

KB: Central to the work are these skeins and the history and memory they are part of. They belong to a larger yarn package I found at my mother’s apartment in the Serbian town of Zrenjanin where I grew up. I created a record for each skein, based on the year and location of its production, took note of its color, material, and weight. After getting an overview of what was there, I picked out three shades of white:

Yarn 1, name: Sandra; Volnarski Kombinat Teteks, Tetovo – Yugoslavia, present day Macedonia, produced in 1981

Yarn 2, name: Nina; Sloga, Zrenjanin – Yugoslavia, present day Serbia, produced in 1970

Yarn 3, name: Brill; Iteks, Ilok – Yugoslavia, present day Croatia, produced in 1969

This small collection of yarns had been kept in a dark and dry space for at least two decades. During that time, lots of things happened in the world and in Yugoslavia, the country where I was born and where I grew up in. As a result of privatization and the transition to a neo-liberal market economy, many factories closed down, and this was followed shortly after by the violent breakup of Yugoslavia during the 1990s .

By tracing the history of the yarns, I unpacked the larger story of my family history, as well as the history of my city and country. The narrative of three generations of women in my family who used these yarns, the narrative of women working in the factories that produced them, and the broader narrative of the rise and fall of the textile industry in Yugoslavia all helped me understand the broader context of the work.

SS: You purchased a loom to create the three pieces of cloth that are at the center of the work, and you learnt how to weave. Can you comment on the importance of this process for the project?

KB: I started to look deeper into the stories of textile making in Yugoslavia in order to see how these might resonate with the story of my own family. Zrenjanin was one of the largest textile-producing towns in the former Yugoslavia. I remember watching my mother make clothes back in the 1990’s. She picked up this craft while she was helping her own mother who in her turn had picked it up by helping her mother when they were both in a labor camp in Poland during the WWII.

The memories and histories that started to unravel in this way were the reason why I wanted to work with a loom. I wanted to bind all these loose threads and storylines together. As a result of this effort, the work Ground Bindings emerged. The three textiles are the very first textiles I ever made with a loom. You can tell by the tension that holds each of them in place. The textiles are 90 by 120 cm each, woven very loosely, which makes them soft, tender, and extremely vulnerable.

SS: Weaving has traditionally been associated with women, not least as a means to be self-sufficient and independent (think of Penelope who wove in order to fend off her suitors). You have written of the three women in your family who owned the three original skeins of yarn that appear on the wall. Is there something “defensive” about your purchase of a loom, whereby you now own not only the raw materials (the skeins/yarn) but also the means of production?

KB: Mythology is indeed permeated with references to textiles and weaving. Take, for example, the ancient Greek story of Fates. Here three sisters are believed to be in control of human destiny: Clotho used a spindle to spin the thread of life; Lachesis measured the thread, while Atropos cut it. The three women in my family also used yarn to maintain life, but also because it brought them joy and warmth. For me, working with the yarn they left behind comes from a desire to build on these stories and relations. Yet it is also a way to consider a specific type of labor: spinning, weaving, sewing, stitching, patching, embroidering, and binding are all linked to a very time-consuming, repetitive type of work process. As such it was long considered “women’s work”, and while weaving provided working women with a certain independence, it was also considered reproductive, hence not as valuable or authentic as men’s work.

Textile materials such as clothing, blankets, and carpets are more pivotal to human history and culture than we may think. However, this highly degradabe material is easily absorbed back into the soil, leaving no traces. As a result, the significance of the women who made these objects is also lost. In a sense, for me, textile making is a way of nourishing, protecting, preserving these different histories and narratives. Being in charge of the raw materials and the means of production is a way of resisting.

Kristina Benjocki. Ground Bindings (Nada, Gizela, Tereza), 2019. Installation view at TENT gallery, Rotterdam. Photograph by Add Hoogendoorn. Image courtesy of the artist

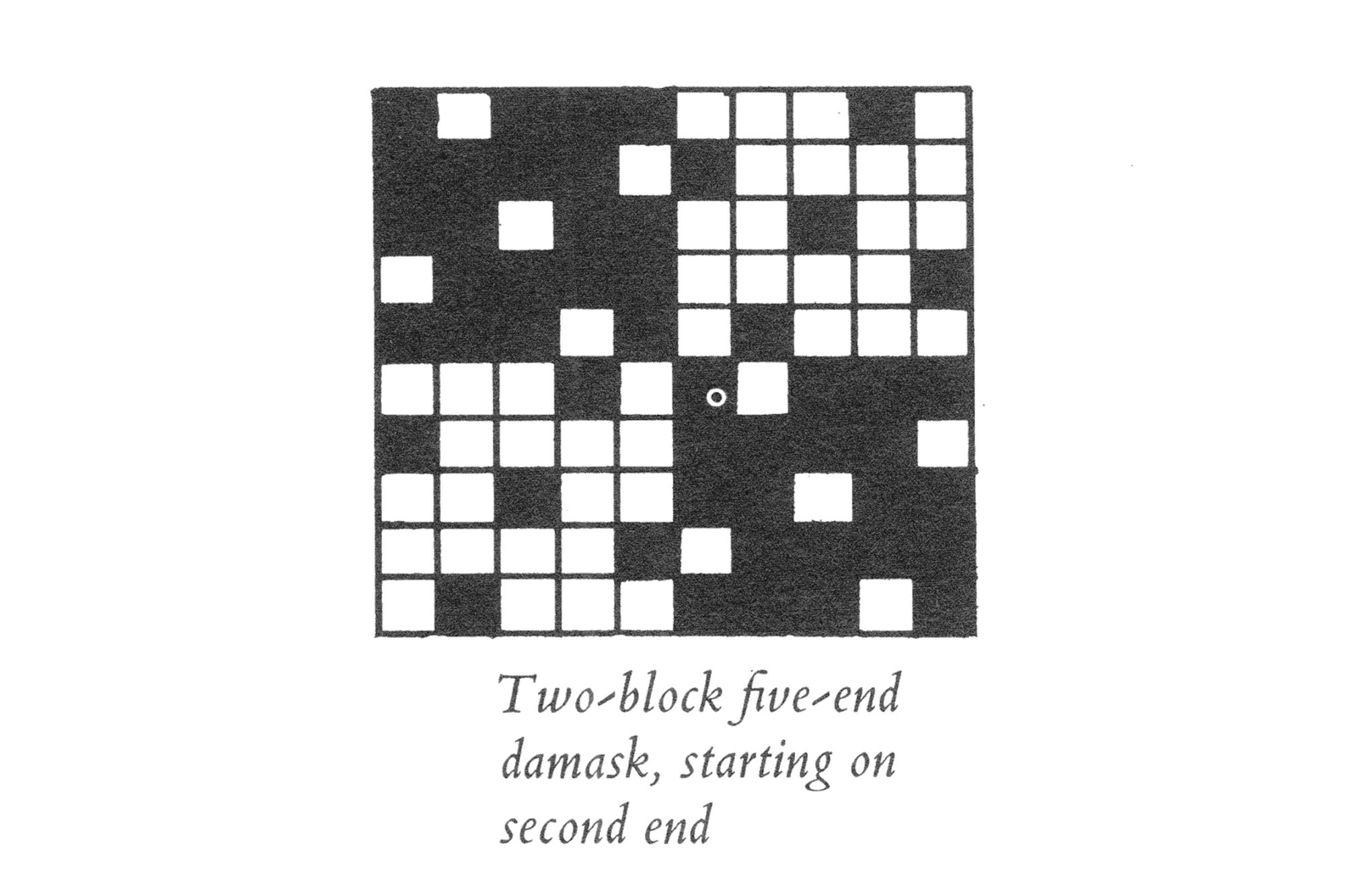

SS: One of the more fascinating aspects of your installation are the accompanying diagrams, the so-called “weaving drafts” that taught you how to weave. Can you explain the relationship between the images, drawings, and text in your installation?

KB: Indeed, I produced the three textiles by reading the weaving drafts that contain all necessary information about the treading, the loom tie-up, and the sequence of weaving operations. The drafts are written in a binary language and provide information about each of the three weaving patterns. In the installation, the skeins are enlarged and printed on the wallpaper. Next to them, a glass shelf shows three labels with information about each of the yarn skeins. Across from them, hanging freely inside the space, are the three woven textiles themselves. Together, the images, drawings, and texts illustrate each step of the weaving process, suggesting that this process can be repeated. Repetition is essential for establishing a pattern, both with regard to the material quality of the textile and to creating a tactile memory, which is central to learning a craft.

Kristina Benjocki. Ground Bindings (Nada, Gizela, Tereza), 2019. Installation view at TENT gallery, Rotterdam. Photograph by Add Hoogendoorn. Image courtesy of the artist

Kristina Benjocki. Ground Bindings (Nada, Gizela, Tereza), 2019. Installation view at TENT gallery, Rotterdam. Photograph by Add Hoogendoorn. Image courtesy of the artist

What emerged in the process of weaving Ground Bindings are three abstract pieces of cloth that arereminiscent of such everyday textiles as tea towels, blankets, curtains, tapestry, or clothing. The images, drawings, and texts in the installation make visible the invisible labor that provides the backbone of our cozy and comfortable domestic life.

SS: I’m interested in the binding drafts and the wool labels (you call them “recipes”) because, in a sense, they are like translations. In order to produce the textiles, you had to apply the drafts’ graphic language to the mechanical operation of the loom. Could it be that translation—ultimately a linguistic form of production—is another concern in your work?

KB: I do see writing and textile making as interrelated. Not only do the words “text” and “textile” share the same root (Latin texere, to weave); weaving as one of the earliest technologies also played an important role in the material history of the written word. Both paper (made from papyrus) and thread (made from flax or cotton plant) find their origin in the natural world. Because of the development and use of the binary language in the weaving drafts, and later in Jacquard’s punch cards, the loom is known to be the forerunner of computing. In my understanding, weaving and work on the loom are based on the translation process that occurs when the weaving draft is read, or rather interpreted. In the case of a hand-operated loom, this translation is never the same. Each new cloth includes glitches and irregularities that I see as an important aspect of the work, much like stories turn out slightly different each time they are being retold.

SS: Thank you!