One on One: Pleurad Xhafa, 200 Million Euro (2020)

The “One on One” series presents timely encounters between ARTMargins Online editors and contemporary artists, usually focused on one recent work. Recently, artist Pleurad Xhafa was among the protesters occupying the National Theater in Tirana in May of this year. Along with the other occupiers, Xhafa was arrested by police, and although he was subsequently released, he is currently facing charges including resisting arrest and illegal gathering.

Raino Isto: 200 Million Euro was originally installed on the stage of the National Theater of Tirana earlier this year, but it was destroyed—physically—together with that building in the early hours of the morning on May 17, 2020, when the Albanian government demolished the theater in an act that has been widely condemned as illegal, both within Albania and abroad.(On the questionable legality of the destruction of the theater, and a summary of the political situation in Albania leading up to its destruction, see Valentina di Liscia, “Open Letter Condemns the ‘Artwashing’ of Albanian Prime Minister’s Politics,” Hyperallergic, May 19, 2020, https://hyperallergic.com/565114/open-letter-condemns-artwashing-albania/ (accessed July 8, 2020). For a full timeline of the developments surrounding the planned destruction of the National Theater, see the social media post by the Vetëvendosje (“Self-Determination”) Movement’s Albanian Office, on Facebook, May 16, 2020: https://www.facebook.com/LVVShqiperi/posts/555949528679836 (available in English here: https://docs.google.com/document/d/1OMEQh1g0fOQiaW6y_rlEYL-7MaZeW-GmkN6r9m8RW_Y/edit?usp=sharing).) Because the work is no longer present, can you describe it?

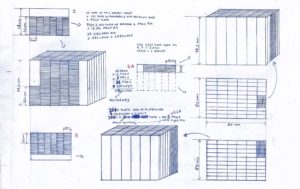

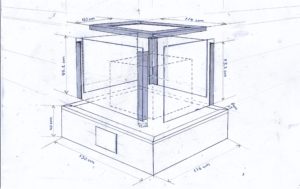

Pleurad Xhafa: 200 Million Euro is comprised of 500-Euro notes printed on A4-size office paper. These notes are protected by a glass cube, which is mounted atop a pedestal. The overall dimensions of the work (including the pedestal) are 139.1 by 130 by 116 centimeters [54.7 by 51 by 45.7 inches]. This dimension was the result of arranging the printed notes in roughly one cubic meter, divided into six columns. These six columns correspond to the six private towers that were initially slated to be built on the public land occupied by the historic theater, together with the new theater building.

Pleurad Xhafa, 200 Million Euro, 2020. Installation on the stage of the National Theater, Tirana, Albania. Created with the support of the Debatik Center for Contemporary Art.

RI: This work explores the theme of corruption, a phenomenon that you’ve examined several times in your previous work.

PXh: Yes, it is a continuation of several works I’ve created in recent years on the topic of corruption and the law in Albania. In fact, it is part of a trilogy that analyzes a cycle of criminal activities carried out in collaboration with the state itself. The shared element within this trilogy of works is the geometric form of the cube: in each phase of the cycle, the cube is composed of a different material (in this case, printed 500-euro notes).

RI: What is the significance of the work’s title?

PXh: The sum “200 million euro” is repeatedly cited in connection with various instances of corruption that have taken place—or are taking place—in Albania. Whenever this sum is mentioned, it immediately suggests associations with secret, illegal activities because it has been used so often to refer to such activities. It has become a kind of mythic sum: not a concrete fact, but a symbolic number. For example, in 2008, several of the diplomatic cables made public by WikiLeaks reported that the Minster of Transportation at the time Lulzim Basha (now head of the political opposition in Albania) had been accused by the Prosecutor General of financial abuses in the amount of 200 million euros. Later, in 2015, the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE) also mentioned the sum of 200 million euros in its confidential report titled “Corrupt Albanian MPs.”(On this report, see Gjergj Erebara, “Leaked OSCE Document Names ‘Corrupt’ Albanian MPs,” Balkan Insight, September 15, 2015, https://balkaninsight.com/2015/09/15/leaked-osce-report-on-albanian-politicians-crimes-makes-waves-09-14-2015/ (accessed July 8, 2020).) According to this report, the current Prime Minister of Albania, Edi Rama, possessed a secret offshore account containing 200 million euros. The report indicates that he was suspected of gathering this amount through bribes given in exchange for building permits during the period 2000–2011, during which time he was the mayor of the Tirana municipality. Finally, in 2018, a detailed calculation made by the local media in Albania asserted that 200 million euros was precisely the amount that the entities involved in the destruction of the National Theater stood to profit from the theater’s demolition, and from the construction of the new theater as well as six new privately owned towers on formerly public property.

Pleurad Xhafa, 200 Million Euro, 2020. Installation on the stage of the National Theater, Tirana, Albania. Created with the support of the Debatik Center for Contemporary Art.

This detail can’t simply be regarded as a coincidence, especially when we see it mentioned over and over again in classified reports by international diplomatic entities. Rather, I think the sum functions as a kind of cipher, a secret code of communication which demands its own method of decryption in order to understand the dynamics behind these events.

I began to think seriously about this code of communication on January 1, 2020, when Albania became the chair of OSCE and Rama, the prime minister, became the head of the organization.(See OSCE, “Implementing Political Commitments Together, Making a Difference on the Ground, Continuing to Strengthen Dialogue to Define Albania’s 2020 OSCE Chair,” press release, January 1, 2020, https://www.osce.org/chairmanship/443215 (accessed July 8, 2020).) In order to make the sum all the more tangible and present, I decided to materialize it in the form of a cube and place it on the stage in the National Theater. This physical space—the stage of the theater itself—would help fulfill the work’s transition from an idea to a concrete reality.

Pleurad Xhafa, 200 Million Euro, 2020. Installation on the stage of the National Theater, Tirana, Albania. Created with the support of the Debatik Center for Contemporary Art.

RI: The protest over the proposed destruction of the National Theater and the construction of a new theater (designed by the famous Bjarke Ingels Group, BIG), together with additional privatized housing and commercial real estate, have gone on now for years. Was this protest more about protecting a particular historic building, or more about rejecting the ongoing privatization of Tirana’s historic center?

PXh: During the eight years of Rama’s government, the historic center of Tirana—including the National Theater—has changed fundamentally. Among these changes have been several schemes suspected to involve the illegal privatization of public property and in the majority of cases there have been efforts to demolish buildings classified as cultural heritage. Of course, the two goals you mention were at the heart of the protest, but I believe it was more than just that. What happened over the course of these two years of continual protest and occupation was a strong challenge issued against the model of government in which a single person (such as the prime minister) can stand above the state and its laws, can steal public land and assert his own narrative upon space, erasing history through corrupt urban interventions. But above all, the protest over the theater, in its determination and longevity, brought to light the social and moral crisis in which Albania now finds itself.

Pleurad Xhafa, 200 Million Euro, 2020. Installation on the stage of the National Theater, Tirana, Albania. Created with the support of the Debatik Center for Contemporary Art.

RI: The demolition of the theater took place during a period of quarantine enacted in response to COVID-19. How had the situation with the theater changed in the weeks prior to its destruction, during the pandemic?

PXh: In the two months leading up to May 17, the situation surrounding the theater had changed considerably, with the matter of its destruction becoming a kind of test for Albania’s new justice system. Now, for example, the organization The Alliance for the Protection of the National Theater has put together a detailed dossier on the demolition and delivered it to the Special Anti-Corruption Prosecutor’s Office.(“Anti-Corruption Prosecution Launches Investigation Into Tirana Mayor Over National Theatre,” Exit News, May 15, 2020, https://exit.al/en/2020/05/15/anti-corruption-prosecution-launches-investigation-into-tirana-mayor-over-national-theatre/ (accessed July 9, 2020).)

COVID-19 was the perfect pretext that Rama needed to eliminate the theater. It allowed the government to sidestep the usual legal channels and act with impunity. What happened on May 17 was a despicable act, one that exploited the fears of the people in order to perpetrate a high crime. The violent protests that began after the destruction produced a chain reaction that has challenged not only the figure of Rama in particular as an artist-politician, but also those who have supported him and who helped create his narrative.

RI: What did the National Theater symbolize for artists, and for the population of Albania more broadly?

PXh: As elsewhere in the world, the theater serves as a space of representation, of imagination, of encounters and conflicts. That is, as a place where one learns to understand oneself more deeply, and to deepen one’s connection with the surrounding community. This is even more true when a theater is a historic building, like the National Theater. Built 80 years ago by the Italian fascists, it was the site of the founding of the Institute of Albanology and at the end of the Second World War, of show trials against dissidents against the Communist Party. The theater was an important part of historical memory and of individual spiritual values, a point of reference for the city of Tirana and for our past.

It’s not accidental that BIG’s design for the new theater introduces a shopping-center approach. This aims at entertainment and simple enjoyment, turning the institution into a product that can ultimately serve political propaganda.

RI: Was this work conceptualized as part of the “permanent collection” of the National Theater, as if the theater itself was a kind of museum?

PXh: There have frequently been popular arguments for the idea that the National Theater should not have been destroyed by the government (although of course now it has been), but should instead have been made into a museum. Personally, I have been against this idea, especially as the situation has developed over the course of the two years during which a protest has taken place to protect the theater.

The immediate protest over the originally planned demolition of the theater in 2018, and later the occupation of the theater—which turned out to be the only way to resist its destruction— not only demonstrated a significant consciousness of the importance of public, commonly-held space, but they also made possible the dismantling and exposure of the presumably corrupt machinations that the government had pinned on the project to build a new theater in the old one’s place. The continual pressure from prime minister Rama to destroy the theater at all costs also ended up creating the need to reflect critically on precisely the political realities of the present.

For more than two years, the occupied space of the theater gathered together citizens who found there the ability to publicly articulate their frustrations, their desires, and their disillusionment. This dynamic process brought the theater back as a concept—perhaps for the first time in Albania—to its origin as a public forum for debate. This is very different from a museum. In this context, placing 200 Million Euro inside the theater was an effort to reflect the urgency of the present moment. To enter into contact with the work, the viewer had to physically climb up on stage. For me, this displacement of the body of the viewer was very important because it broke the famous ‘fourth wall’ of the theater. But in this case the wall was not broken by the actor, as usually happens, but by the spectator.

Pleurad Xhafa, 200 Million Euro, 2020. Installation on the stage of the National Theater, Tirana, Albania. Created with the support of the Debatik Center for Contemporary Art.

RI: Was the work completely destroyed along with the theater?

PXh: Yes, physically, it was destroyed, but I don’t consider the work to be lost. The violent act that was carried out the morning of May 17 simply added a new dimension to the work’s possible meanings.

RI: You are a co-founder of the Debatik Center for Contemporary Art (DCCA),(See the group’s website, https://debatikcenter.net.) and when 200 Million Euro was installed in the theater, that group issued a call for other independent art spaces and organization to openly proclaim their stance against the demolition. Why was the solidarity of the artistic community in this case so important?

PXh: It must be said that—with the exception of a few artists and scholars—the long silence of the Albanian art scene brought to light two possible standpoints: either total indifference about what happened to the theater, or else agreement with its proposed destruction, in order to preserve interests tied closely to the government or the Tirana municipality. The government’s illegal activities during the period of COVID-19 made the issue of the National Theater a critical one, and the reaction needed to be swift and clear. Therefore, DCCA called on arts institutions in the country, and the reaction from many of these institutions was immediate—this was very interesting. This politically united stance brought together—perhaps for the first time—the majority of the visual arts organizations in the country, openly contradicting the claims of Edi Rama, the most celebrated politician in the global art world.

Pleurad Xhafa, 200 Million Euro, 2020. Installation on the stage of the National Theater, Tirana, Albania. Created with the support of the Debatik Center for Contemporary Art.

RI: What possibilities do you see for continued resistance to state power in Albania?

PXh: It is difficult to foresee how the protests over the theater will develop, or how other acts of resistance in the future will play out. But one thing is certain: the myth that Albania does not protest has been disproven, and this could be the beginning of a new kind of relationship between the public and political power. The theater’s example gives the public a good reason to continue resisting because during these years of protest over the building’s planned destruction, the government’s empty words were finally overcome by the truth, and the emperor was revealed to be without clothes.

This conversation was conducted in Albanian via email in May–July 2020. It has been translated and edited for clarity.