On the Concept of the Museum of Contemporary Art in Ukraine: Svitlana Biedarieva in Conversation with Olya Balashova and Yuliia Hnat

For many years, Ukraine has experienced a growing need for a Museum of Contemporary Art that would function as the first state-run collection focused on acquiring and exhibiting the work of contemporary Ukrainian artists. The attempts to create such an institution began in the early 2000s, but thus far have been unsuccessful due to political and sociocultural factors. In 2020, a nonprofit association was created to work in an applied way on the development of theconcept of the museum, with the involvement of key experts in contemporary art and culture. In this interview, art historian and artist Svitlana Biedarieva speaks with Olya Balashova and Yuliia Hnat, representatives of the initiative group for the creation of the museum.

Svitlana Biedarieva: I would like to start by asking you to expand on the history of the creation of the first state-run museum of contemporary art in Ukraine. How did the concept develop?

Olya Balashova: This is a process that has been going on since, at least, 2004. During this time, six private museums emerged as a response to the public discussion on the creation of a contemporary art museum, such as the PinchukArtCentre in Kyiv, the Museum of Modern Art of Odesa, and the Korsaks’ Museum of Contemporary Ukrainian Art in Lutsk. But these private institutions do not benefit from any governmental programs. When we as a group began working on this question in 2017, we understood that a new museum would have to be a state institution, so that both the museum and its collection would become part of the state’s cultural policy. Then we tried to consolidate people around this idea within the existing National Art Museum of Ukraine. However, we realized that there were many obstacles to finding any consensus because the latter museum is not yet fully reformed. Its structure is inherited from an inert post-Soviet institution that, perhaps, would like to respond to the contemporary vision of museums’ function but doesn’t do so completely. So instead, we focused on developing the idea of a new type of institution.

Yuliia Hnat: What is most important is that in Ukraine the government should take responsibility for the display and collection of contemporary art in museums. We speak about the inherited research bias with its binary vision of official and unofficial practices, and about how the state cultural policy developed a controlling function of cultural processes [in the Soviet Union—SB]. There are also the postcolonial and post-totalitarian traumas to contend with, as well as the questions of how to lead the system’s de-communization and de-ideologization. So we need to focus on integrating contemporary art (an independent, liberated phenomenon) into the state apparatus in order to build an infrastructurefor culture and education. The support of this new art could be in line with the processes of separating culture from the haunting Soviet past.

SB: What do you propose for the development of the new museum of contemporary art? What has been done so far and what still needs to be done? Perhaps one of the most important achievements is that already an institutional structure exists, in the form of consultatory boards in which leading experts in art and culture have been involved.

OB: We have created a nonprofit organization called the Museum of Contemporary Art (MOCA NGO). Its main function is to perform the function of a forum, an agora, where specialists in contemporary art and culture can work together on the museum’s concept. The organization has three boards. The first is the Research Board, which focuses on creating a basis for the collection, the selection of potential works and artists, and the general framework for the acquisition and cataloging of artworks. Then, there is the Museum Board, which is concerned with more practical, spatial resolutions for the building of the museum, and the general organizational structure of the future institution. Finally, there is the Organizational-Legal Board, which addresses questions about copyrights, the legal framework for the new museum, and all the questions of the mediation between the government and the public.

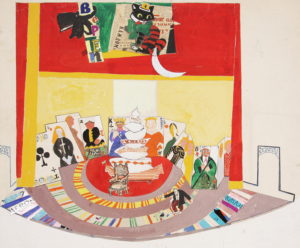

Alla Horska, That’s How Guska Died, 1962. Sketch of a theatre set.

The collection strategy focuses on works created from the 1950s to today. The selection of artists ranges from the works of official and dissident artists, shistdesyatnyky (the Sixtiers)(The Sixtiers were a generation of important Ukrainian artists, writers, and filmmakers distinguished by their anti-totalitarian dissident views.), such as Ada Rybachuk, Volodymyr Melnychenko, and Alla Horska, and contemporary artists working in a variety of media in the years following Ukraine’s independence in 1991.

YH: So far, we have worked closely with architects and urbanists, focusing on already existing buildings in downtown Kyiv, or alternatively, the development of a new project in the center of the city. The relevant negotiations are underway with the city administration. We’ve also organized several board meetings to crystallize the common vision of themuseum’s strategies. Currently, we are confirming the list of artists who have influenced cultural life in Ukraine and beyond its borders. The primary task now is to systematize the information we have and use it to build a Digital Archive of Ukrainian artists, and then later to organize the actual physical collection.

SB: Why is the Digital Archive of Ukrainian contemporary art necessary? Also, does creating such an extensive archive pose any challenges, such as securing all the necessary copyrights? How will you overcome these challenges?

OB: It’s difficult to imagine, even for specialists, what Ukrainian contemporary art looks like in its totality because everyone refers to some fragments that they saw in an exhibition or witnessed firsthand, but there is no representative museum collection. There are only two private collections—the Boris Grynyov and Victor Pinchuk collections—that are regularly on display. We started from the premise that in order to conceptualize a new museum we first needed to gather what it will contain, even if only virtually. We decided to create the Digital Archive as an instrument for our research. We want to bring together collections of contemporary Ukrainian art of any scale existing today and give the public access to them, to increase networking and collaboration.

We are currently creating the platform, buying program software, developing the interface, and confirming the copyright owners who will register their works on our platform, following the protocols of Europeana, a cultural heritage platform funded by the E.U. However, the task of copyrights is a complex one, and we are working with artists and collectors to obtain rights for our use of digital copies. The situation regarding intellectual property, especially in the art field, is currently very contentious in Ukraine. There is simply no legal way to ascertain the copyrights of many of the works that are on display and in collections now.

When the Digital Archive is complete, we will be able to survey the panorama of artistic practices in Ukraine since the 1950s. This database will be donated to the Museum of Contemporary Art, as soon as it is officially launched.

SB: Is now the right time to launch such an ambitious project as a Museum of Contemporary Art?

OB: Perhaps it is impossible for the current state apparatus in Ukraine to work on a project like this because the state itself is not sufficiently reformed to approach any project that is not linked to the Soviet vision. During the period of Ukrainian independence, cultural policy hasn’t evolved much from Soviet times. Even if we look at the budget of the Ministry of Culture, it is very rooted in these practices that were characteristic of Soviet times. For example, the Ministry supports folk collectives and circuses, and lavishly finances entertainment and propaganda-focused projects. On the other hand, contemporary art—with its open perspective, critical attitude, and out-of-the-box thinking—began to be supported by the government only recently, as in the case of the Festival of Young Ukrainian Artists.

Likewise, next year Ukraine will have the first participation at the Venice Biennale without a scandal. In every prior edition, there was some confrontation with the government, except for those years when the Ministry simply gave the pavilion to the PinchukArtCentre for their own projects.

YH: This is a sign that the machine is moving; little by little the cultural system is gaining the momentum to support contemporary art with all these small interventions that need be systematized. The creation of a new museum would be the culmination of this systematic process.

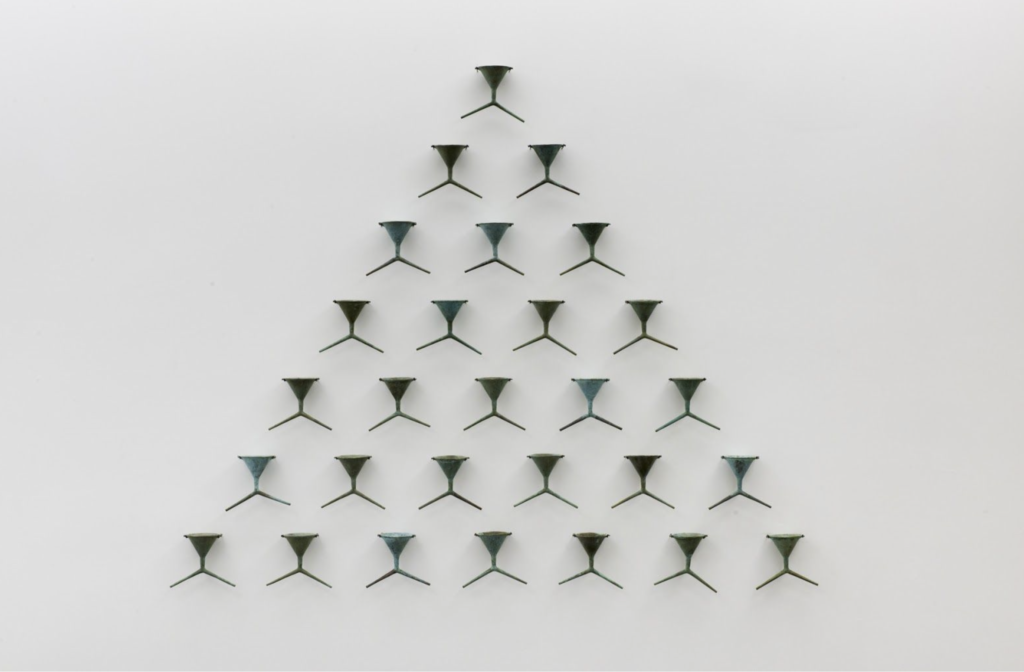

Pavlo Makov, The Fountain of Exhaustion, 2015.

SB: It would be interesting to know more about the Venice Biennial, and how it was possible to reach a negotiation after so many conflictive years.

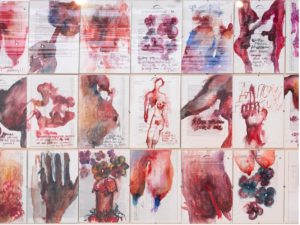

OB: The selection of the four finalists for the Biennial was very representative this year: the Foundation Izolyatsia; Maryna Shcherbenko with Maria Kulikovska; Tetiana Kochubynska; and Boris Filonenko, Liza German, and Maria Lanko with Pavlo Makov. All of the curators placed Ukraine in some broader context. The first proposal was rooted in representing Ukraine as part of Eastern Europe, but different from how the Russian media discusses it with its all-unifying perspective that even such liberal media as The Calvert Journal pursues. Another approach was to show Ukraine as aunique cultural space through Maria Kulikovska’s project The President of Crimea, which offered Ukrainians a distanced view of ourselves to show what is important for our social space and the problems we face. Lastly, Tetiana Kochubynska’s proposal situated Ukraine as part of the “global village.”

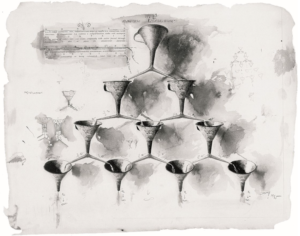

Pavlo Makov, The Fountain of Exhaustion, 2015. Technical drawing made in 1995.

Pavlo Makov won with his project The Fountain of Exhaustion. Curator Boris Filonenko emphasized that Makov is an artist working at an international level, and whose project clearly describes the condition of Venice and the world in general—the condition of uncertainty and vulnerability. The Fountain of Exhaustion talks about Venice as a disappearing city, vanishing under the water. It is not a fountain of the exuberance of life, but of its lack. The installation consists of funnels that filter water one into another until the last drop; when the water reaches the bottom, it practically disappears. The Venice project is not about Makov as a Ukrainian artist who represents Ukraine in some way, but about Makov as a Ukrainian artist who simply exists and deserves attention on his own terms.

YH: This project is finally about the act of being and not the desire to be.

SB: Makov’s project is a great metaphor for what’s going on both in the larger world and in Ukraine. We can observesimilar processes of exhaustion or a newly emerging “void,” but there is a hope that this void can be filled withsomething profoundly new or reconstructed from the past.

OB: We need to prove all the time—even to ourselves—that we can be interesting artistically because of the absence of a space where the history of art can unfold. This does not allow seeing ourselves, our own reflection, our identity. That is why a museum of contemporary art is important: it can stop this process of losing one’s image, where the reflection appears as a ghost for a short time then vanishes again.

YH: Because now successful projects appear in fragmentary ways, and then they only exist as memories.

Maria Kulikovska, Constitution of the Autonomous Republic Xena-Maria, 2020. From the project The President of Crimea.

SB: Taking up the question of identity and the necessity to respond to the global or regional placement of Ukrainian contemporary art, in the discussions by the museum’s Research Board, a proposal was made to start the chronology of the collection from the year 1954, beginning with the Thaw. Then the Board decided that it would be better to tie the beginning to when Ukraine acquired Crimea in that same year. This represents a moment when Ukraine became “complete” in its contemporary form, as recognized by the Ukrainian government. It also represents a conscious choice not to connect to the traumatic part. How does such a consideration impact the narrative this collection wants to establish?

OB: I think that in Ukraine’s reality, it is impossible to omit the traumatic part. And I understand why colleagues would like to get rid of the burden of the tragic events of the 20th century in these “bloodlands,” as Timothy Snyder calls them.(For the detailed analysis of the history of Ukraine as part of Eastern Europe between Communist and Nazi regimes see Timothy Snyder, Bloodlands: Europe Between Hitler and Stalin (New York: Basic Books, 2010).) We have only now started to understand the scale of this catastrophe, of the Holodomor and the Holocaust inBabyn Yar, the site of the massacre of Jewish people in Kyiv during World War 2. However, I also understand why some of the members of the board would like to start from a blank slate and continue this discussion elsewhere, leaving the Museum of Contemporary Art as a kind of neutral space, detached from the past.

I think that’s a utopian idea. Instead, this experience of the past should be worked through, it should be reconsidered, and bridges need to be built between the trauma and its contemporary interpretations. Even as an absence, thisexperience is still real today, for example, in the memories that my parents did not have, or that my grandmother partly had but never talked about. Several generations that survived the experience of repression, collectivization, hunger, industrialization, and the Holocaust, wouldn’t tell their children about this, trying to protect them. Therefore, subsequent generations could not transmit it either. And only now does this become part of our experience (due to the archives that, for instance, opened after the Maidan protests), not as the past but as part of the present.

All these things call for a certain distance, also because there is this very Soviet notion of “pure art” that is situated outside of any political dimension. And this prevents the cultural sphere from problematizing history or contemporaneity, prevents it from adopting a historically critical attitude on art, as we can see in many Ukrainian museums.

SB: This is like the difference between the postcolonial and anticolonial, where the anticolonial is against the past colonial experience, and the postcolonial takes some elements, digests them, and converts them into part of actual discourse. It sounds like you are aiming at balancing these approaches in some way.

YH: We are aiming to nurture a multiplicity of narratives, to make it possible not to build a single narrative but rather to explore various possibilities, from perspectives that might even exist in tension. And we need a safe space where these perspectives can be addressed critically.

Very often when people hear about this type of official project, of a state museum that we propose with colleagues, they question how it is possible to create an independent space with several perspectives as an official institution, to museify it, understanding that Ukrainian society has a strong demand for liberty and independence in all aspects. There is also the deep problem of institutionality here. Yevhen Hlibovytsky, a former journalist and long-term strategies expert, has described the difference between post-totalitarian and postcolonial spaces. In the first case, there were firm and strict rules that oppressed the life of society; in the second case, there was no right to establish rules at all, together with the fear to attempt to establish any rules. And these two mechanisms highlight the problem of institutionality in Ukraine.

OB: When we speak about the museum, we always need to discuss the more general problems of the institutional gap in the system. We have transparent borders between the levels of organization and thinking about the museum—the context that has to be created and discussed at the level of the Ministry of Culture impacts and is impacted by the creation of such a museum. The appearance of this museum project makes possible some processes, but at the same time the cultural processes that exist now, especially after 2014, also enable its development. These are mutually conditioned cases.

SB: I would like to emphasize the potential role of the museum in the formation of not only the institutional framework but also in the development of the field of art history in Ukraine. I understand that there are some problems with teaching art history and currently the production of research in the field is very narrow.

OB: Undoubtedly, the appearance of a state institution would be beneficial for teaching and research. We have good art historians of the Early Modern period, art before the 19th century, sacral art, and folk art. However, the tradition of teaching art history did not receive a thorough revision in the last thirty years—it still focuses on the formal school or on detailed theoretical analyses. But there are constantly discoveries in the sphere of art history, new findings are described and analyzed, so there has to be permanent construction.

Art history reconstructs itself with the help of archives, and in this aspect the discipline was largely mutilated in Soviet times—only its fragments were researched. Today, if we speak about 20th-century art, and especially, contemporary art of the current century, the numerous changes that affect the discipline globally are not revealed in the study programs in Ukraine today. This is hugely problematic since there is no self-reflection in these programs of study, no effort to take account of how new information must transform existing narratives.

The only way to break out of this hermetic bubble is for scholars to gather and create their own intellectual environment—this happened in art with the group R.E.P. (Revolutionary Experimental Space), for example, when the artists in the early 2000s gathered and exchanged ideas that broke with the habitual art academy’s schemes and went out to the international space. The same happens now with theoretical circles in the humanities. Their breakthroughs are based on mutual interests in the topic, but they aren’t grounded in any existing system. However, this intellectual cohort can’t provide a profound change until there is a solid institution through which the state supports all these achievements with relevant practice and methodology. Currently, the profession of the “curator” doesn’t even exist as a field that one could study in Ukraine.

R.E.P., We will R.E.P. you!, 2005. Street action.

There is one private institution that has been an important player in both local and international cultural spaces, and that is the PinchukArtCentre. It is important for the development of artistic processes: they raised numerous generations of curators and theorists who work with archives. It is a key institution that protects the memory of contemporary art—a task that is too complex for both the National Art Museum of Ukraine and any other private institution that works with contemporary art. At the same time, their contributions are easily ignored by state universities and museums. Students do not ignore them, because collaboration and participation are important for them, but on the level of university departments and professors, that work is ignored. To integrate their legacy into the educational process, theremust be a strong lobby from a state-funded institution dedicated solely to contemporary art.

R.E.P. Patriotism, The Fence, 2010.

SB: You touched upon a very important problem. How can the Museum of Contemporary Art be integrated into this ecosystem if it will be a public museum?

OB: First of all, as a public institution, the work it does becomes visible. If it is a state institution, it joins the Ministry’s programs. A professional institution would construct relationships that would link those holding power in government and the academy, and link them to researchers and artists. The academy would then be obliged to prepare specialists to work on the state’s commission for such a museum. This is a domino principle that receives the impulse from the state, with its proactive collaboration with all the stakeholders of this process. The precedent principle is very important here—state administration here has such a logic that if something has happened, it is impossible to change or to move backwards. If Ukraine has decided to participate in the Venice Biennial, for example, and the Ministry is responsible for this, then the schedule, workload, calendars, and so forth, emerge.

YH: There is the culture of sprinters and the culture of marathoners. Right now, because of all the turbulence and the radical changes in government, we have a well-developed culture of sprinters, oriented towards immediate results but without continuity. We have a more active, more dynamic civil society. Recent years show that the government also tries to react proactively, but without any attempt to make the results sustainable. What we aim for is to freeze the moment and to reach a stable outcome for our work. And now we need to resolve this paradox, to create a process that is at the same time sustainable and swift.

This interview was conducted in Kyiv in August 2021.