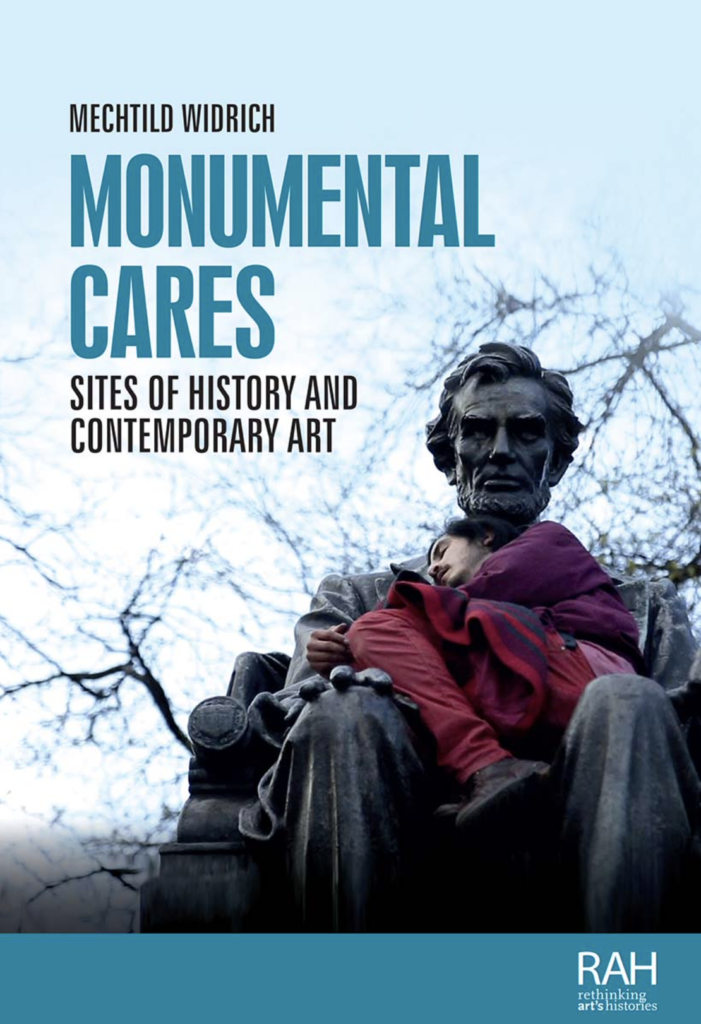

Monumental Cares: Sites of History and Contemporary Art

Mechtild Widrich, Monumental Cares: Sites of History and Contemporary Art (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2023), 256 pp.

The presence and absence of monuments, their authenticity and role in public discourse is the main topic of Mechtild Widrich’s new book, Monumental Cares. We live at a time when this issue has gained more than academic importance, as monuments are central to the politics of caring—caring for community, history, and justice. Being familiar with Widrich’s previous work, I have already utilized it in a critical situation. About a year ago, I participated in a public debate at Vancouver’s Urbanarium, a public hub for incubating ideas about the city. The debate was about the preservation of colonial markers in Vancouver, with two speakers arguing for keeping monuments and street names that celebrate of British colonizers and two advocating for their removal. The occasion was the toppling of the statue of John Deighton, a.k.a. Gassy Jack, a 19th-century bar owner in Vancouver’s city core who married (and raped) two Squamish women, one of whom was only twelve years old. Two local activists argued for the removal of the statue, whereas two academics, of which I was one, were assigned by the organizers to argue for its preservation. The argument we presented did not result in our victory but it did confuse our activist opponents, who expected that the architectural historians would defend the city as an “archive” of the colonial past. What we argued was that it was the performance of the (recorded) toppling of the statue that created a political statement and not the absence of the statue itself. We argued that actually preserving Gassy Jack and toppling or mutilating it on a regular basis would be more effective than just getting rid of it, and provided examples of memorial objects as sites of political performance.

By presenting this argument we partially cheated, and we were not particularly original. We borrowed our premise from Mechtild Widrich’s book Performative Monuments: The Rematerialization of Public Art (2014). In this volume, the author uses J.L. Austin’s notion of “performative” utterances—that is, of acts as statements—to re-examine performance art of the 1960s and 70s, and practices of performative commemoration from the 1980s and 90s. Here, Widrich offers an analysis of the Monument Against Fascism in Hamburg-Harburg designed in the 1980s by performance artists Johen Gertz and Ester Schalev-Gertz, an example we used to illustrate our point at the Urbanarium.

By presenting this argument we partially cheated, and we were not particularly original. We borrowed our premise from Mechtild Widrich’s book Performative Monuments: The Rematerialization of Public Art (2014). In this volume, the author uses J.L. Austin’s notion of “performative” utterances—that is, of acts as statements—to re-examine performance art of the 1960s and 70s, and practices of performative commemoration from the 1980s and 90s. Here, Widrich offers an analysis of the Monument Against Fascism in Hamburg-Harburg designed in the 1980s by performance artists Johen Gertz and Ester Schalev-Gertz, an example we used to illustrate our point at the Urbanarium.

Almost a decade after Performative Monuments, Widrich has published another important book on historical markers: Monumental Cares. The book is a provocative volume that is academically rigorous, and it will enrich the public debate on commemoration with its sophisticated reflections on notions of temporality and authenticity of historical markers, siting, and public participation, at a moment when monuments have been at the forefront of political activism. The title of Widrich’s book indicates two concerns. One is the “care” for, or engagement with, political causes. The other is concrete, physical “care” for the monument as a material, sited instrument of negotiating relationships of power, claims to collective memory, and dissemination of ideas about history. Widrich attempts to simultaneously discuss the materiality of the monument, rather than discursive history while at the same time resisting the erasure of human agency that resulted from the “material turn.” She does this by probing what authenticity of a site means in the age of digital dissemination. This is a significant task, especially having in mind Widrich’s understanding of monumentality as inclusive of ephemeral practices, performances as well as art embedded in political protest, such as the infamous “pussy hats.” She frames her discussion in terms of the notion of “multidirectionality” of the monument—the shifting and multiplicity of sites, audiences, political strategies, as well as the polyvalence of the material.

As an academic volume meant to bridge scholarship and public debate, Widrich’s book builds upon the momentum created by very recent activist volumes, such as Karen Cox’s book on confederate monuments, No Common Ground (2021), and Angelika Fitz’s and Elke Krasny’s Critical Care: Architecture and Urbanism for a Broken Planet (2019). What Widrich brings to the table is the problematization and expansion of the notion of care, as well as a successful attempt to bring into the activist fold recent texts that introduce human agency into radical materialism of the recent decades, Giuliana Bruno’s Surface: Matters of Aesthetics, Materiality and Media (2014), and Antoine Picon’s The Materiality of Architecture (2020). In the book, Widrich also relies on the theoretical framework established by Michael Rothberg’s Multidirectional Memory: Remembering the Holocaust in the Age of Decolonization (2009).

Widrich’s book is structured around six themes: site-specificity, shifting audiences for commemoration, geography, reversal of monumentality, transparency, and realism. The first chapter on site and site-specificity is about how sites figure not only as places where history happens but also as places that have history in themselves. She claims that mediation – the dissemination of sites and events by means of computers and phones – actually amplifies the authenticity of the site. As a case study, Widrich analyses the work of Alexandra Pirici: first, her re-enaction of the 1962 incident when a bricklayer was murdered trying to cross the Berlin wall, and then her work in front of the Bucarest “House of the People” turned into the Museum of Contemporary Art. In the first work, Widrich looks at what a performance means for audiences that might or might not remember what it recreates. Considering the second, she looks at Pirici’s postcards featuring her performance as commemorations of a commemoration, pointing out the endless chain of re-historicizing as a situated material practice. She also evaluates this condition in the work of Emilio Rojas The Grass is always Greener and/or Twice Stolen Land, performed in Vancouver in 2014, in which the artist unfolded a “snake” of grass leading from the University of Britich Columbia campus to the Musqueam Indian Reserve and filmed this 25-hour performance that refers to both colonial history and Musqueam oral tradition. Widrich asserts that a successful site-specific work of art is one that embraces parallel histories, multiple audiences, and the historicity of the site itself.

The idea about multiple audiences and their visibility is elaborated in the second chapter, focused on commemorating the Holocaust in Germany in an age when witnesses are gone and lived memory has died with them. She looks at how in Germany—as an immigrant society, populated by recent arrivals from eastern Europe, Turkey, and the Middle East—the Holocaust might acquire different meaning for different kinds of German citizens, and examines how citizenship is defined in terms of access to history and commemoration. Widrich focuses on Steinplatz in Berlin Charlottenburg, where a monument to the victims of National Socialism created in 1953 is placed next to the earlier monument to the victims of Stalinism, erected in 1951: the site in this case is used to relativize the Holocaust. The fact that the Holocaust can and is always re-contextualized and reinterpreted is a starting point for Widrich to ask what re-contextualization means today and for which publics. As an example of a piece that does not accept a homogenous understanding of the public, Widrich cites the installation on Steinplatz executed by the student artist/activist team mmtt, which added monuments to alternative histories, wrapped in plastic, to existing monuments, and Yael Bartana’s Orphan Carousel in Frankfurt commemorating the evacuation of Jewish children in the 1930s with a carousel inscribed with words of goodbye between children and parents, pointing out the power of this project to communicate, in a simple and unpretentious way, to multiple audiences.

In her third chapter, on geographies of art history and commemoration, the linking of different sites through commemorative intervention, Widrich discusses a wide array of projects, from Cary Young’s Body Techniques, the National Memorial for Peace and Justice in Montgomery, Louise Bourgeois’s and Peter Zumthor’s Steilneset Memorial in Norwah, Ai Weiwei’s F.Lotus in Vienna. She examines them through the lens of “radical geography” and Dolores Hayden’s understanding of sites as repositories of memory. For Widrich, history cannot be extricated from geography—and vice versa. The monument that would most closely correspond to the concept of radical geography and the historicization of landscape is Jonas Dahlberg’s July 22 Memorial—a surgical cut through a landscape overlooking the island of Utoyakaia where a massacre took place.

The fourth chapter, “Reversing Monumentality,” looks at commemoration in Romania after 1989 and its capacity to re-historicize the Communist past through subtle rather than colossal gestures. Widrich looks at the work of Dan Perjovschi, Historia/Hysteria, a photo performance in which a miner and “golan” (or hooligan, in Ceaușescu’s terminology) face each other for three hours a day in the street (not noticed by passersby) and are then photographed. Widrich claims that this performance is effective because it is quiet, and minimal, referencing the history of censorship, a context in which protest had to be unnoticeable, quiet. She also writes about Ana Lupaş ’s Rag Monument of heavy black cloth installed on racks in front the Intercontinental on University Square, symbolic of Romania’s flirtation in the West during the Cold War as well as its role as a site of surveying student protests in 1990. Widrich examines the possibility of using the site as historical material and the power of interventions that oppose monumentality of Communist and/or western architecture owned by the state such as the InterConti. She asks questions crucial specifically for an Eastern European monument, such as the “Hall of the People” and InterConti. Is InterConti Western? Is the Palace Romanian, despite Maoist and Stalinist influences? What does it mean for it to be Romanian in an age of tourists making “hee-hee-hee selfies with Ceaușescu”?(Dan Perjovchi, qtd. in Widrich, Monumental Cares, p. 131)

Widrich’s main concerns—the definition of public sphere, its homogeneity, and the power relationships that commemoration entails—are developed in the chapter that follows, “Reflections.” Widrich writes about the reproduction of modernist art tropes for new audiences, using the notion of transparency as a lens through which to explore this problem. She discusses Duchamp, Hannah Wilke, Walter Benjamin, and the fetish of transparency in modernism as both a political metaphor and in concrete terms, as in the case of the material transparency of glass. At the center of her discussion is Monica Bonvicini’s Don’t Miss a Sec’, a glass-clad public toilet encasing the visitor in a one-way looking glass that complicates the notion of asymmetrical visibility as power by creating an object in which the one inside is uncomfortable, and in which public and private spheres are reversed. Widrich stresses that it is the materiality of glass that puts the acts of seeing and social context of the gaze at the forefront. For her, the analogy of the glass surface is the photographic plane, the realist register of the 19th century, describing photographic commemoration as a window to the world outside that is most powerful when it renders this world strange.

The last chapter of Monumental Cares is devoted specifically to realism. She starts with a photograph of Ai Weiwei lying prostrate on a beach in Lesbos, where the Syrian toddler was found dead after an unsuccessful migrant sea crossing. She compares the photograph—taken by Rohit Chawla and exhibited at the India Art Fair in 2016—to Daumier’s famous Rue Transnonain, a lithograph depicting a massacre perpetuated by the French National Guard in 1843. She looks at the relationship between the form of a political work and the modes of its dissemination, under the circumstances where an intimate drama is widely distributed. Widrich’s analysis of this comparison has broad resonances today: she uses it to question whether the practice of using mass media—in 19th century and today—is a co-option of the commercial machine, whether it affects the reality of lived experience, and whether the detachment from the event through aesthetization is in fact a good thing, or a profound problem.

Ultimately, the most important arguments Widrich makes in Monumental Cares are those about the heterogeneity of audiences, the site as a historical object, and her constant probing of the relationship between materiality and agency. It is especially interesting to look at how these assertions are made in the context of non-Western histories. What, for example, does Steinplatz with its monuments mean to a person born in East Germany? Is Steinplatz as alien to them as it is to migrants from the Balkans and the Near East? Is the understanding of monumentality different on the other side of the Iron Curtain, where the erection of Stalinist skyscrapers (recently discussed so well in Katherine Zubovich’s Moscow Monumental (2020)) marked the beginning of the Cold War? What does modernity, with its myths of transparency and monumental strategies, mean in contexts that are not culturally pure, in which we have cross-cultural melanges, such as the mixing of the skyscraper form and Stalinist aesthetics or the mixing of democratic and state capitalism in hotels such as InterConti?

Widrich does not answer these questions, and they certainly warrant further exploration. But she does offer a possible direction in which this discussion can unfold. As her most provocative argument, she suggests that the gap between the monument and lived experience—in the midst of the destabilization of traditional understandings of “authenticity,” brought about by the passage of time, cultural hybridization, and digital dissemination—is not necessarily a bad thing. In her view, the inauthenticity of the site in terms of cultural and experiential purity actually offers the potential for reinterpretation and makes it possible to include new publics in the politics of commemoration. This in turn can give a voice to those who are not necessarily rooted in a place, or considered citizens. Widrich’s most salient assertion is this: as objects that make publics visible, monuments need to be multidirectional and polyvalent, in order to reflect those changing publics. As sites are remade, and they need care as part of the consistent remaking of the history they harbor.