Live Solidarity — Art Workers and Feminist Artistic Organizing in the Post-Yugoslav Region

Equating all types of work and workers in his writing, Edvard Kardelj, one of the main ideators of the Yugoslav workers’ self-management system, set the scene for the understanding of the role of artists in Yugoslav society.(Edvard Kardelj, Pravci razvoja političkog sistema socijalističkog samoupravljanja (Beograd: Komunist, 1978), p. 25.) The idea of class solidarity and the equal value of work—regardless of it being intellectual or physical—was embraced, and many initiatives followed this idea, such as the art program at the Ironworks complex in Sisak, in present-day Croatia, where workers assisted artists, and collaborated with them in the creation of sculptures, from 1971 to 1990. The program was enacted upon the conviction that art should be constantly present in industrial complexes, according to the socialist ideology that sought to bring artists and workers closer together in shaping the new social(ist) reality.(Artists’ involvement in the building of a new society was not a unique Yugoslav case but was also present, for example, in the Soviet Union, see: Iva Glisic, The Futurist Files: Avant-Garde, Politics, and Ideology in Russia, 1905–1930 (DeKalb, Il: Northern Illinois University Press, 2018).)

Following the period of conflict in the 1990s and the disintegration of Yugoslavia, the Yugoslav successor states introduced the neoliberal democratic paradigm, adapting their markets and shifting their economic and social policies to fit global (and more particularly EU) demands. This process, vested in the idea of progress and Europeanization, saw a gradual destruction of the welfare state, catering to global capital, the dispossession of workers, and re-traditionalization of women’s social roles. Following the same path, the art sector went through seismic changes as well, embracing a national cultural paradigm or else self-marginalizing, and developing a managerial approach and the profit motive as a new direction for the cultural sector and state-sponsored projects.(Branislav Dimitrijević, “Koraci i raskoraci: kratak pregled institucionalne koncepcije i izlagačke delatnosti Muzeja savremene umetnosti 2001–2007,” in Prilozi za istoriju Muzeja savremene umetnosti, ed. Dejan Sretenović (Belgrade: Museum of Contemporary Art, 2016), pp. 315–45.)

As Igor Štiks and Srećko Horvat describe in their 2015 book Welcome to the Desert of Post-Socialism, what happened during the so-called transition period was “general impoverishment, huge public and private indebtedness facilitated by a flow of foreign credit, widespread deindustrialization, social degradation, depopulation through diminished life expectancy and emigration, and general unemployment.”(Srećko Horvat and Igor Štiks, eds., Welcome to the Desert of Post-Socialism: Radical Politics After Yugoslavia (New York: Verso, 2015), p.2.) Criticizing the almost complete lack of scholarship critically examining the introduction of neoliberal capitalism in the region during and after the open hostilities were ended, the authors also note the importance of looking at and examining Yugoslav heritage, which could provide a model for thinking about alternatives to present political and economic regimes, in the region and beyond. While the promise of a better life after socialism had failed, and academia still seemed reluctant to look more closely at the Yugoslav past beyond the tropes of nostalgia, conflict, and nationalism, artists working in the post-Yugoslav region increasingly turned to Yugoslav heritage. In this past, they sought models for organizing, and ways to fight the national and nationalistic policies and memorialization practices that political elites adopted after the conflict in order to negate the heritage of Yugoslav socialism. In doing so, these artists not only revealed the injustices of the present system, but also emerged as political actors who did not shy away from reminding the public of the socialist past and the benefits that accompanied it, while remaining aware of its negative aspects. Rejecting any type of nostalgic reverence for the prosperous past long lost, several artists embarked on projects that adopted the ideas of class solidarity, workers’ rights, and gender equality to examine present conditions in the post-Yugoslav region, casting the shortcomings of the newly established neoliberalism in a sharp light.

This article turns to three works—Rena Rädle and Vladan Jeremić’s Ironworks ABC, Tanja Ostojić’s The Lexicon of Tanjas Ostojić, and Andreja Dugandžić and Adela Jušić’s Labor of Love—that examine the heritage of the past in the present and establish a dialogical link between the present social order and the Yugoslav past. These works address several aspects of society most directly and visibly impacted by neoliberal capitalism, including workers’ organizing, labor conditions, and gender roles, in order to promote greater class and gender solidarity in the region that is currently lacking. By revealing the shortcomings of the currently established social and economic relations, these artists also put forward the idea of collective organizing, a strategy that is reflective of the self-management system, as a possible course of action.

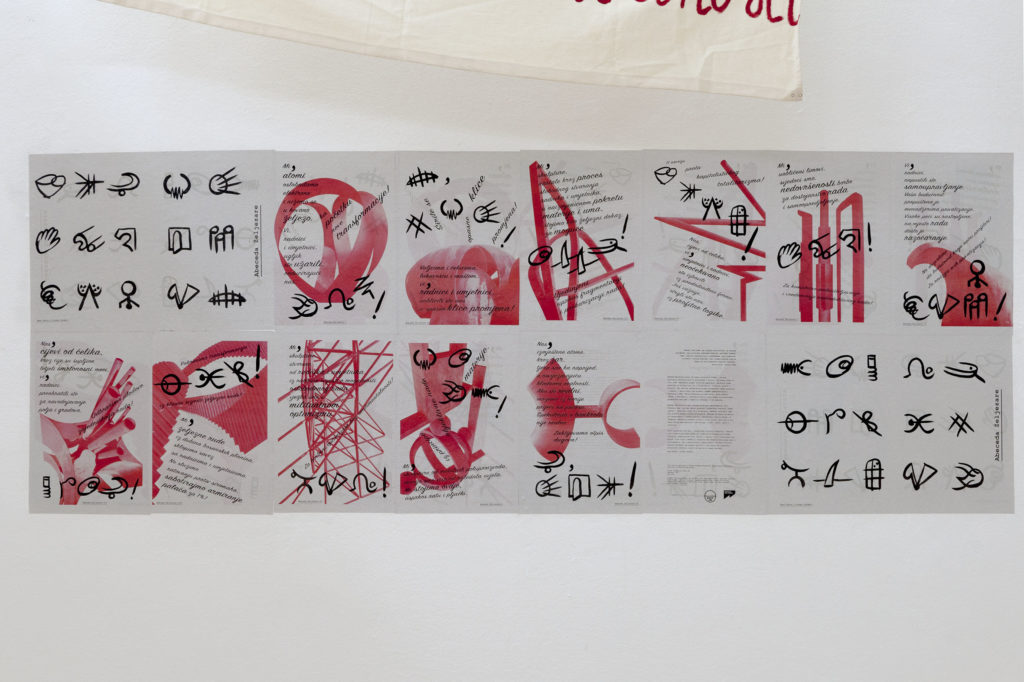

Rena Rädle and Vladan Jeremić, Ironworks ABC. Newspaper wall installation, SIZ, Rijeka, 2015. Photo by Rena Rädle

Writing about solidarity, philosopher Arto Laitinen explains that in political solidarity, which could be called “a response to moral deficits” but also a “struggle for more particular goals,” there is a network of agents and a class of agents “whose claims and interests the network represents and stands in solidarity with.”(Arto Laitinen, “From Recognition to Solidarity: Universal Respect, Mutual Support, and Social Unity,” in Solidarity: Theory and Practice, Arto Laitinen and Anne Birgitta Pessi, eds. (Lexington Books, 2014), p. 141.) The artists and works discussed here, which address the living and working conditions of workers and specifically women in the post-Yugoslav region, do not exercise solidarity as a form of direct political action that would immediately affect the lives of those involved (although the work of Tanja Ostojić achieves this to some extent), nor do they take the position of advocates for these groups. Instead, they create solidary performative actions that foreground knowledge about the past as a place for reflection from which solidarity networks could be reactivated while recognizing their own precarious social status (as artists) within new social and economic parameters as well. Knowledge about the positive aspects of the Yugoslav past was obliterated from public discourse with the advent of nationalism, and the fragmentation of the formerly unified workforce and women as a particular class in Yugoslav society followed, with devastating consequences. The destruction of the welfare state and the (re)introduction of traditional gender roles and organizing, also charted along the lines of ethnic divisions, further disintegrated the social base, which was rendered unable to act collectively.

The works examined here draw attention to what has been lost, but they also serve as a starting point for new transformations. In that sense, these artists are agents that stand in solidarity with disadvantaged classes and “actualize worthwhile goals” with the hope that they will turn into “(normal) social and institutional reality sustained by bonds of social solidarity.”(Laitinen, p.141.) In doing so, they cross the boundaries of states, regions, gender, and class to create works that address collective interest, and which establish a creative depository of activist and artistic gestures that can be reactivated across time and meridians. The possibility of reactivation becomes crucial as the aspects of the created solidarity networks also speak to global circumstances characterized by increasing precarity and racial and social injustices, and offer a productive way of thinking and performing art in the circumstances of global crisis.

Rena Rädle and Vladan Jeremić: Ironworks ABC

In recent years, Rena Rädle and Vladan Jeremić, an artistic duo from Belgrade, have staged performances in several cities around Europe, including Oslo (Rolling Classroom, 2019), Levanger (Red Winter, 2014), Tirana (Paris Commune Revisited, 2019), Bor (Workers’ Collective, 2013), Belgrade and Graz (Fragile Presence, 2016, 2018), Bucharest and Trondheim (Didactic Drawings, 2013, 2015), Rijeka (Potentials for Militant Creativity, 2017), Palermo and Bitola (Deaf Shoes, 2018), Sisak (Ironworks ABC, 2015), and Tallinn (Real Struggle, Fake Estates, 2016). These works address local political and social issues, including the prevalence of rampant capitalist accumulation and dispossession, uneven distribution of profit, class struggles, the dismantling of the welfare state, and center–periphery relations in Europe mapped out over West/East and capitalist/former-socialist geographies.

Rena Rädle and Vladan Jeremić, Ironworks ABC. Banner, Sisak (Caprag), 2015. Photo by Rena Rädle

Ironworks ABC (Abeceda Željezare) deals with the now-defunct Ironworks complex in Sisak, Croatia, and the sculpture park Caprag in the workers’ neighborhood. Once employing over 14,000 workers, the complex was also a vibrant place of artistic production, unique in its approach to art creation. Between 1971 and 1990, workers and the invited artists collaborated on sculptures—a unique event bridging the class and social division of labor—which are now preserved in the park in the workers’ neighborhood Caprag. Writing about the initiative, historian Zlatko Čepo notes that the direct contacts between workers and the painters and sculptors working in the Ironworks colony broke the artificially created gap between industrial workers and those engaged in cultural production, and opened the processes of integration on a more humane basis.(Zlatko Čepo, Željezara Sisak 1968–1973 (Sisak, 1973), p. 160.) Other authors, such as Vladimir Maleković, also addressed the importance of bringing artists and workers together. Maleković explains that the idea for the colony came from the notion that certain contradictions between artistic and industrial work should be surpassed and that material and spiritual production should be more integrated, which would, as painter Hajrudin Kujundžić concludes, lead to a more “harmonious socialist society.”(Kolonija Likovnih Umjetnika Željezare Sisak 1971–1990. Povijesni Pregled. Izložba Gradskog Muzeja Sisak (Sisak, 2012), pp. 8, 18, 53.) The sculptures from the Sisak Ironworks Artists’ Colony, as the initiative was named, were equally attributed to artists and workers, and they evidence a significant move towards this goal.

Rädle and Jeremić used the sculptures still in place in the park as a starting point in their investigation of present-day precarious working conditions, opportunities available to workers and artists, and fraught privatization in the post-Yugoslav region. They stylized the sculptures’ forms to create a sign language, and printed these characters in the Ironworks ABC newspaper and on textile banners that they then hung in the park. The work also includes poetic texts, the so-called ‘speech of the sculptures,’ written by the artists, and contemporary slogans of social movements in Croatia, which address the processes of privatization and their consequences. One such speech by a sculpture reads:

“You,

workers,

abandoned self-management.

Your future is left to the managers of privatization.

The furnaces have melted, disappointment flowed to the workplace.

We are not allowing the future to be woven by war profiteers!

For the audit of every privatization!”(Maja Ćirić, Rena Rädle, and Corina L. Apostol, Transformatorium (Novi Sad: Museum of Contemporary Art Vojvodina, 2021), p. 167.)

Ironworks ABC foregrounds the story of workers’ engagement in the cultural life of Yugoslavia as a background for the examination of current conditions and the defunct smelting industry in the region. It showcases the differences between the status of workers and artists now and then, including their position not only in industry but also in the broader cultural life of the country. The work also reintroduces class struggle as a field of exploration and political engagement, lost to the nationalist discourses explored in research from the 1990s onward. The precarity characterizing the present-day lives of workers in former Yugoslavia, and the ways they are precluded from actively engaging in working conditions and other aspects pertinent to their labor, are evoked through both the texts and the new alphabet developed from sculptures. The link with the past is established not through nostalgic reminiscence, but through using creative engagement that transforms the remnants of this past into a new activist language that, deployed in the present, seeks to activate solidarity networks between workers as a basis for a collective class engagement.(The artists are equal partners to workers in this endeavor; in several of their other artworks, Rädle and Jeremić also emphasized the similarities in position between artists and workers within the neoliberal context, proposing a unifying front of all workers against the injustices of the new social and economic regime.)

The solidarity with workers takes the form of acknowledgement of their difficult social and economic position (in which artists equally partake) often ignored by political elites, support of their “worthwhile goals” in the conditions of neoliberal capitalism on the periphery, and through providing a model for possible future organizing between artists and workers.

“We,

sculptures,

formed through the process of emancipated labor

of workers and artists,

in the alternating motion of matter and mind,

we stand as iron-wrought evidence, of the possible.”(Ćirić, Rädle, and Apostol, p.167.)

Direct aesthetic recollections bring the memory of the past model back in the present while the “speech of the sculptures” voices the grievances and calls for a unifying front and a joint action of all workers.

Tanja Ostojić, Lexicon of Tanjas Ostojić, 2012-18. Colaborative art project. Workshop, Goethe-Institut Belgrad, January 2017. Photo: Marija Piroški. Courtesy/ copyright: Tanja Ostojić

Tanja Ostojić: The Lexicon of Tanjas Ostojić

Tanja Ostojić has been a strong presence in the regional art scene since 1994. Her art, based in performative and participatory practices, explores the issues of labor, migration, economy, and gender politics in Europe. Produced over a period of six years, The Lexicon of Tanjas Ostojić (2011-2017) is a piece of feminist research into social and cultural biographies of women bearing the same first and last name as the artist. As Ostojić explains, she was interested in exploring how different social conditions for women have changed after the Yugoslav disintegration: “I had the impression that the new national states, new religious identity, wars, transition, and poverty in the region were a huge step backwards for what were, in large part, emancipated Yugoslav women.”(Tanja Ostojić, “Transformative Encounters: From the Author’s Perspective,” in The Lexicon of Tanjas Ostojić (Live Art Development Agency, 2018), p. 9.) The project also goes against the trend of “erasing all traces of Yugoslavian tradition and history” and it particularly resurfaces the labor conditions of the artist’s name-sisters.(Ostojić, pp. 9-10.)

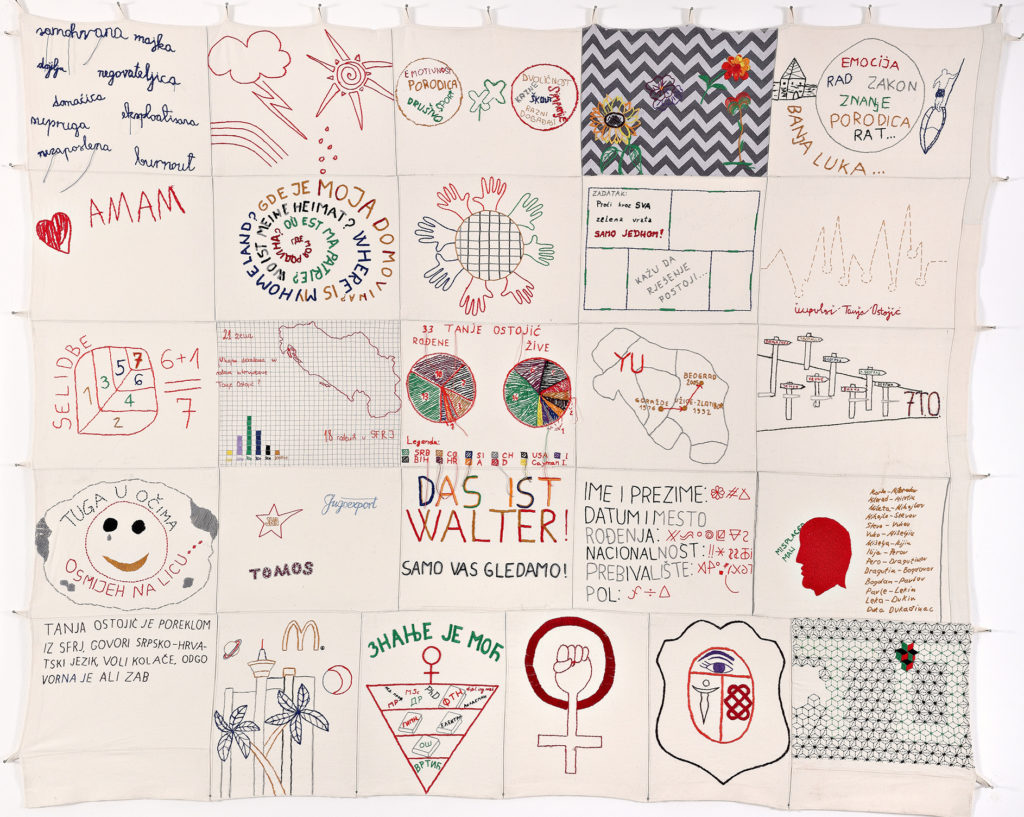

Embroidered Lexicon of Tanjas Ostojić, 2017. Documentary Embroidery/embroidary on Cotton, 200 X 160 cm. Coauthors: Jelena Dinić, Tanja Ostojić (Banja Luka), Tanja Ostojić (Berlin), Tanja Ostojić (Trn), Tanja Ostojić (Udine), Tanja Ostojić-Guteša, Tanja Ostojić-Petrović, Tanja Petar Ostojić, Tatjana Tanja Ostojić, Tatjana Ostojić (Alabama), Sunčica Šido i Vahida Ramujkić. Workshops facilitators: Tanja Ostojić (Berlin) and Vahida Ramujkić. Photo: Nikola Radić Lucati. Courtesy/copyright: Tanja Ostojić

Ostojić takes multiple positions in this work—as an artist, researcher, and collaborator who dives into various phenomena that affect the lives of persons who share her birth name. The work consists of several parts, creating “a complex psycho-geographical map of relations between proper name, identity, subjectivity, and belonging,” comprising photos, exhibitions, embroidery workshops resulting in a large-scale tapestry, various objects created during or after the workshops, video recordings of collective actions, maps tracing the movement of Tanjas across the world, and a book containing these Tanjas’ testimonies and other texts.(Suzana Milevska, “The Potency and Potentiality of Transindividuality in the Lexicon of Tanja Ostojić,” in The Lexicon of Tanjas Ostojić (Live Art Development Agency, 2018), p. 141.) The Lexicon is also an investigation into transindividuality and a form of relational mapping, as curator and theorist Suzana Milevska explains, where the life trajectories of Ostojić and her collaborators are brought together and intertwined in the creation of a collective identity that opposes “the society of control.”(Milevska, p. 144.) Interested in the commonalities between Tanjas Ostojić, the artist engages with these individuals’ cultural, social, and political backgrounds, proposing a different way of thinking about and presenting individual destinies. Autobiographies narrated by each Tanja are brought together into an archive of personal destinies where similar language, the post-Yugoslav experience of migration and work, and gender roles create an image of a Tanja and Tanjas where what is shared is also what defines each of them individually. Strict division between individuals is replaced by a multitude, as a site through which a new, collective form of agency can be forged.

Tanja Ostojić: Lexicon of Tanjas Ostojić: Migration map of 30 Tanjas Ostojić, 2013. Drawing in pencil on aquarelle paper, 254 x 138 cm. Photo: Nikola Radić Lucati. Courtesy/copyright: Tanja Ostojić

The mixture of individual stories in The Lexicon and the visual responses create a unique archive of the marginalized women in the restructuring of post-Yugoslav societies, which also works as a place for regaining agency. Following the idea of collective action as an empowering site, and grounded in the Yugoslav practices of collective organizing, The Lexicon of Tanjas Ostojić examines the changes women born in the Yugoslav region have endured in the last few decades with a focus on labor conditions, providing a space for thinking about these changes that thus far was lacking, for mapping them, and for creating an alternative, empowering community that can act together. The act of solidarity thus establishes itself in this work in the form of direct collective organizing and acting as a group, where individual experiences are shared, and a supportive environment is created for future actions. Being part of a solidary community that shares similar experiences allowed each individual to forge their own strategies for acting, which, in several cases, have brought a profound change.(Ostojić, p. 23.) Many Tanjas testified that having been a part of this project and talking about themselves helped them cope with personal problems and pushed them to change their conditions by leaving an unhappy relationship or abusive employer, seeking education, or escaping their prescribed role within a traditional family structure. Similar to the other works examined here, The Lexicon supports the goals of those who experienced negative effects of wars and new regimes through the form of a “collaborative work that counters the alienated, removed, and violent work demanded by the new conditions of labor.”(Bojana Videkanic, “Lexicon of Tanjas Ostojić and Feminism in Transition,” Sociologija 60, no. 1 (2018): p. 156.)

Andreja Dugandžić and Adela Jušić: Labor of Love

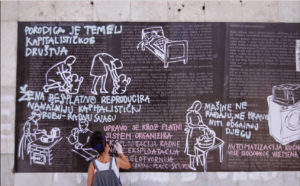

Adela Jušić and Andreja Dugandžić, Labor of Love. Digital collage and graffiti in public space. Produced for group exhibition: “My house is your house, too”, Sarajevo, Historical Museum of Bosnia and Herzegovina, 2014. Photo: Courtesy of the artists

The final artwork of interest here is Labor of Love (Rad ljubavi), a collaborative performance by Andreja Dugandžić and Adela Jušić that reflects on the idea of love and labor in socialist and post-socialist times. The work was first performed for the Historical Museum of Bosnia and Herzegovina in 2014, for the festival My House is Your House, Too, and was later also repeated in Maribor (2014), Saint Petersburg (2015), and Ljubljana (2016). Inspired by the co-founders of the Wages for Housework Movement—Selma James, Mariarosa Dalla Costa, and Silvia Federici—the artists addressed the issue of the unpaid labor that women do at home, and reflected on emancipatory events from the Yugoslav past.(Jelena Petrović, “Labor of Love and Other Stories: Post-Yugoslav Feminist Narratives and Artbased Practices,” in Narrative Counterpublics of Gender and Sexuality, ed. Silvia Schultermandl et al. (Bielefeld: transcript Verlag, 2022), pp. 101–18.) The link between love and labor has been made in the past, especially in relation to the capitalist order, where women are expected to raise and love a workforce that will then be exploited by the capitalist machinery. The first critiques of such a treatment of women came during the socialist revolutions in Europe, when these social conditions were questioned and more egalitarian social relations proposed. However, as Jelena Petrović notes, this was not enough to overturn the material conditions of social reproduction, leaving women still locked in the nuclear family as the main providers of care and reproductive and domestic labor.(Petrović.) The question of love and unpaid women’s labor, although tackled by socialist feminists, has remained unresolved, and has become a point of interest for feminist artists in the post-Yugoslav region.

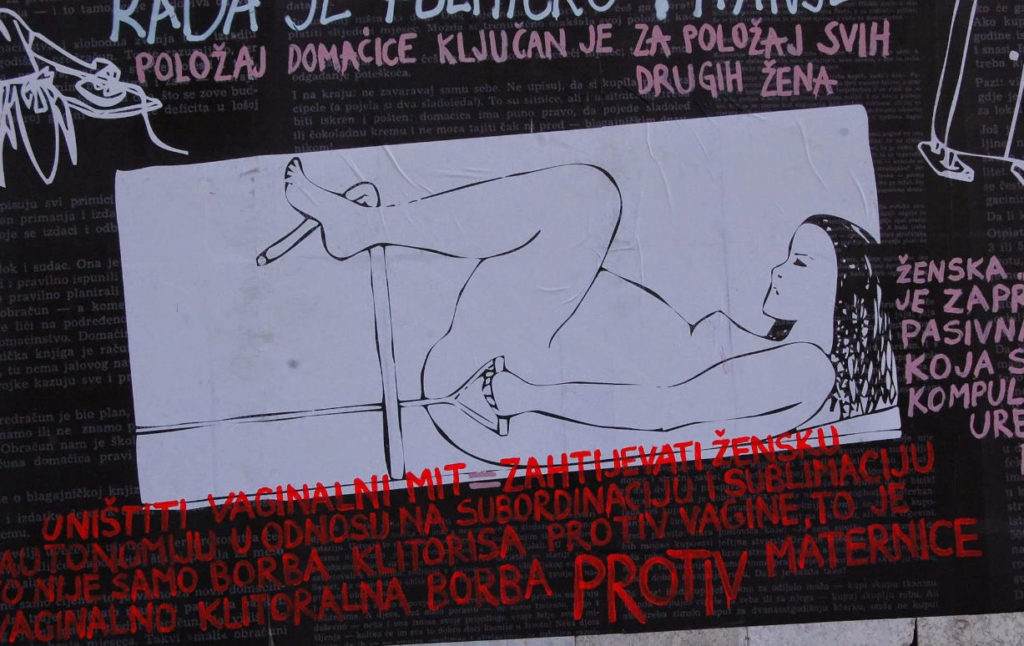

Adela Jušić and Andreja Dugandžić, Labor of Love. Digital collage and graffiti in public space. Produced for group exhibition: “My house is your house, too”, Sarajevo, Historical Museum of Bosnia and Herzegovina, 2014. Photo: Courtesy of the artists

The socialist revolution in Yugoslavia provided a blueprint for a more equal society where women’s emancipation followed economic and social emancipation from capitalist models of production. However, with the Yugoslav disintegration, the women’s question (as happened with many other aspects of social organizing) went through a process of “re-traditionalization, instrumentalization and naturalization of women’s identities, their social roles, and symbolic representations.”(Žarana Papić, “Europe after 1989: Ethnic Wars, the Fascisation of Social Life and Body Politics in Serbia,” Filozofski Vestnik 23, no. 2 (2002): p. 194.) Within new social conditions, the ideas propagated by the Women’s Antifascist Front (AFŽ, established in 1942 as part of the resistance to occupation during the Second World War) and the front’s involvement in questioning women’s unpaid domestic labor in Yugoslavia gained new currency. Andreja Dugandžić and Adela Jušić engaged in collecting and archiving documents and artworks related to the AFŽ, which revealed that although women’s emancipation was propagated, the patriarchal tendencies remained strong within the Yugoslav Communist Party, and the socialist promise of women’s emancipation failed to be achieved in full. Following the changes from the 1990s, the situation worsened with the normalization of “heteropatriarchal notions of sexuality and love.”(Petrović, p. 110.) Drawing from previous times, Dugandžić and Jušić designed the performance Labor of Love, using public space as a soundboard to bring widespread attention to ideas drawn from the Marxist feminist statements regarding women’s emancipation and labor articulated in the 1970s. Pointing to the regression taking place with the transition to a neoliberal order, the artists used acrylic colors and spray paint to paint the wall outside the Historical Museum of Bosnia and Herzegovina in Sarajevo with slogans and images reflecting women’s position within this new order. “Family is the very pillar of the capitalist society”; “Free of charge, a woman reproduces the vital capitalist good – labor force”; “The struggle for denaturalization of housework is a political struggle. The position of housewives and the struggle for their liberation is determinant for the position of all other women”—the artists painted these phrases on the wall, emphasizing the need for joint solidary actions on the part of all women if the current condition is to be changed.(Andreja Dugandžić and Adela Jušić, “Labor of Love.”)

Adela Jušić and Andreja Dugandžić, Labor of Love. Digital collage and graffiti in public space. Produced for group exhibition: “My house is your house, too”, Sarajevo, Historical Museum of Bosnia and Herzegovina, 2014. Photo: Courtesy of the artists

Conclusion

All three of the works explored here address different themes that are, at the same time, rooted in the new capitalist order of the post-Yugoslav reality: the exploitation of workers and how this exploitation is intertwined with questions of gender and identity. While the post-socialist space of the former Yugoslav republics joined the open market system, the modes and modalities of capitalist exploitation remain similar and reflective of the practices at work in the period prior to the Second-World-War, when the Yugoslav economy developed on the periphery of the global market in relations of semi-coloniality and dependency.(Sergije Dimitrijević, Strani Kapital u Privredi Bivše Jugoslavije (Beograd: Grafičko preduzeće Vuk Karadžić, 1952).) The advent of post-socialist neoliberalism brought with it shifts in social and cultural organization as well, moving the entire art sector into a position of dependence on market structures. As the selected works demonstrate, the struggles for equality, solidarity, labor rights, and emancipation—the markers of the socialist period—return in practices that examine the failures of the neoliberal system. Yugoslav heritage, negated and expunged from the public discourse by political elites, thus gets reactivated through art in the present moment.

In the current conditions of global crisis, this looking back performed by artists could at the same time be a look into the future, where—as dissatisfaction with the neoliberal system grows—new modalities of social structuring need to be imagined and exercised, based on class solidarity and collective organizing. Besides the artworks selected here, other artists, organizations, and art groups (including KURS collective, Igor Grubić, and the Association for Culture and Art—CRVENA) developed their practices along similar lines of interest and aesthetic choices. Together, they are creating a depository of ideas, aesthetic approaches, and actions that lead the way to a new redistribution of knowledge about the past and the present that can form a basis for action.

The aesthetic aspects of the selected works, borrowing from other forms of social activism and avant-garde movements of the 20th century as well as the official art of the Yugoslav period—in the form of public engagements, street art performances, participatory projects, the printing of zines, and public sculptures—accentuates the critical potential of these works towards current conditions. The references to the Yugoslav past and affirmation of the past regimes’ ideals and aesthetics establishes itself as a form of a critique of the present moment, while at the same time the past is used as a possible guiding post for future organizing.(Igor Štiks, “Activist Aesthetics in the Post-Socialist Balkans,” Third Text 34, no. 4–5 (2020): pp. 461–79.) While social movements and activism can spill over and travel across borders in activating similar organizing elsewhere, the potential of these and similar art practices in provoking broader action is yet to be evaluated. However, while the circumstances of the post-Yugoslav region may seem singular, the examination of social conditions reveals similarities with global tendencies in the last few decades. The struggle for a more just world continues, with art offering a place for political (re)creation, and an armory for action.

The title of this paper is borrowed from the Association for Culture and Art—CRVENA’s initiative Živi solidarnost! (Live Solidarity!) initiated on March 8, 2010.

This article is part of the Special Issue on Art and Solidarity. You can read the other articles included in the issue: