Kultura Dva in Digital Space: A Virtual Museum of the USSR

Preface to the Museum of the USSR

— Vladimir Paperny (Los Angeles)

A quarter of a century ago, I started looking at the shapes of the Soviet architecture, trying to “read” them as cultural utterances. The results were published in Russian under the title Kul’tura dva (Culture Two) first by Ardis Publishers (1985) then by Moscow journal Novoe literaturnoe obozrenie (1996). The English translation will be released by Cambridge University Press next year.

A few years ago, a young Russian architectural student at the University of Utah, Olga Filippova, started thinking in the opposite direction. She took the basic concept of “Culture Two,” namely the existence of two conflicting cultural mechanisms in Soviet culture-the one based on movement, horizontal axis, futurism and equality, the other, on stability, vertical axis, past and hierarchy-and tried to turn them back into architectural shapes. The results are presented below as The Museum of the USSR.

|

Preface to the Museum of the USSR

— Vladimir Paperny (Los Angeles)

A quarter of a century ago, I started looking at the shapes of the Soviet architecture, trying to “read” them as cultural utterances. The results were published in Russian under the title Kul’tura dva (Culture Two) first by Ardis Publishers (1985) then by Moscow journal Novoe literaturnoe obozrenie (1996). The English translation will be released by Cambridge University Press next year.

A few years ago, a young Russian architectural student at the University of Utah, Olga Filippova, started thinking in the opposite direction. She took the basic concept of “Culture Two,” namely the existence of two conflicting cultural mechanisms in Soviet culture-the one based on movement, horizontal axis, futurism and equality, the other, on stability, vertical axis, past and hierarchy-and tried to turn them back into architectural shapes. The results are presented below as The Museum of the USSR.

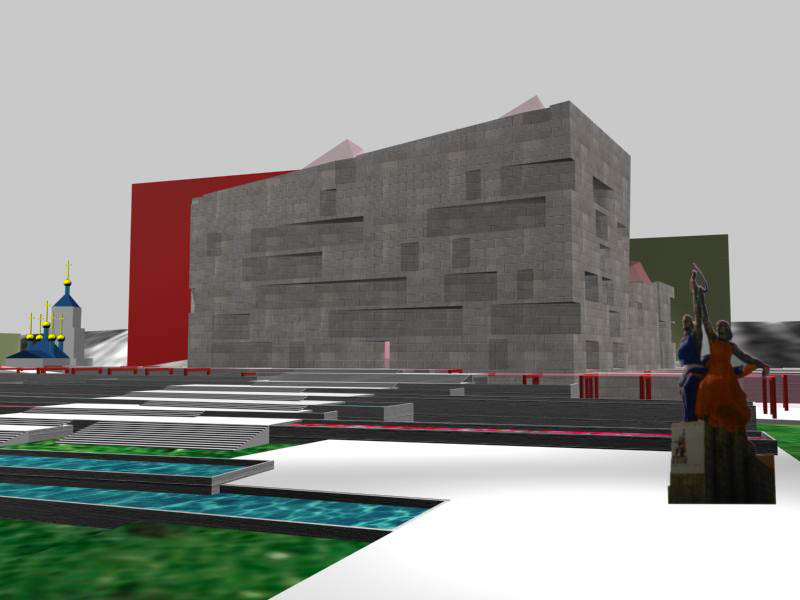

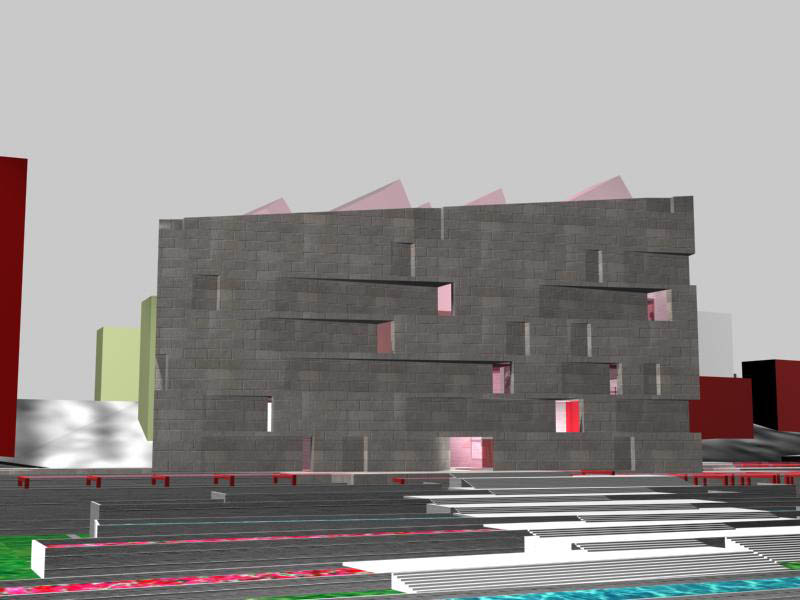

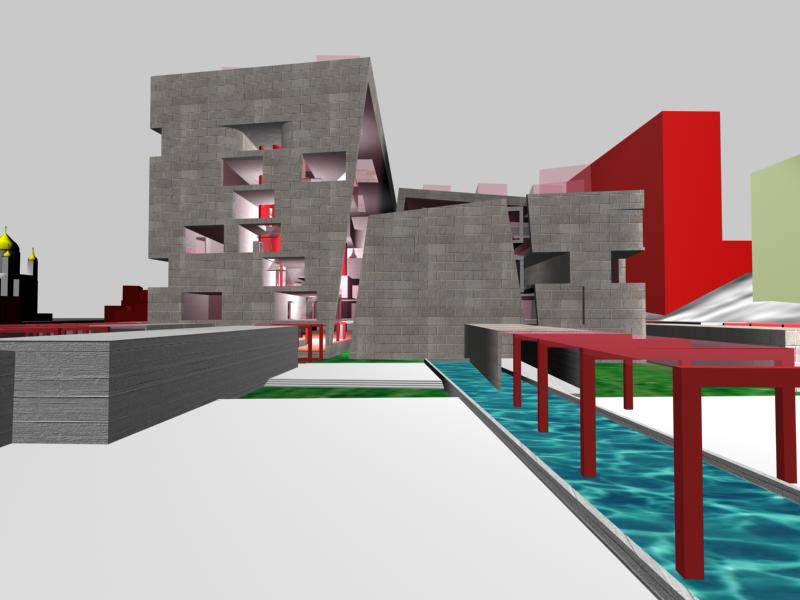

The question that immediately arises is that of the legitimacy of her procedure. The shapes corresponding to the concept of cultures One and Two already exist in pre-Stalinist and Stalinist architecture. Is there a need to revive them? Filippova’s answer is that she is trying not to revive Soviet architectural shapes but rather to offer a post-post-modern view of the post-Stalinist analysis of these shapes. The shapes she is using in her design are surprisingly close to the Russian avant-garde itself. Even the oppressive monolith representing Culture Two looks very cheerful, being pierced by the streaming bars of Culture One. Filippovas optimism, not unlike Frank Gehry’s, is based on technology. The whole project is created and rendered in 3D Studio Max (one of the most sophisticated 3D modeling programs), while interactive animated tours are created using VRML language. None of this would have been possible five years ago.

Olga Filippova belongs to the Russian generation that doesn’t have any first-hand experience of Stalinism. To her, both Culture One and Two are amusing and exciting cultural forces that are great fun to play with. The enthusiasm of the Russian avant-garde was to a large degree based on electricity. “Since electricity,” wrote Mayakovsky in 1922, “I completely lost interest in nature. An imperfect thing.” The enthusiasm of the new generation of American architects (and Filippova partly belongs to it as well) is based on computer technology. Olga’s sketchbook consists of (in addition to pencil drawings) video clips, PDF files, VRML files, MAX files, etc.

When I asked her if there was a chance to have the museum built, she said: “perhaps on the Internet.” Maybe it’s already more important to have a museum built in the Internet than on Prechistenskaya Embankment?

Project for a Museum of the Former USSR

— Olga Filippova (Salt Lake City)

The Museum of the USSR is an architectural project designed for the city of Moscow. Using the means of architecture, the museum models the principles, nature and experience of Soviet reality, its culture and society. Before translating them into the language of architecture, I identified the basic social and cultural foundations of life in the former Soviet Union. For example, one might say about the United States that it is a country of “equal opportunities”. About Soviet society one might say that it was “hierarchically structured”. I see culture as a complex structure governing all aspects of human endeavor. I had to study the entire spectrum of social and cultural activities in the former Soviet Union in order to understand its specific culture. Further, since each of these activities (such as architecture, to give but one example) comments on, reflects, and represents the larger culture of which it is a part, it was necessary to analyze Soviet culture like a language, finding in the process the connections between its disparate elements. These cultural explorations led to an understanding of the architectural forms necessary to construct The Museum of the USSR.

Apart from The Andrei Sakharov Museum and Public Center, the greatest influence to my museum project was Vladimir Paperny’s well-known study, Kul’tura dva, where the legal, political, literary, and, especially, architectural codes of Soviet reality and history are arranged on a matrix defined by two cyclical cultures (Culture One vs. Culture Two). Culture One covers the period of the historical avant-garde in Russia, beginning with the revolutions of 1917. Culture Two comprises Socialist Realism as the negation of the aspirations of the historical avant-garde and the imperative that all art follow but one goal, a.k.a., the representation of the happy future of mankind under communism. Paperny views Culture One and Culture Two as purely functional, cognitive principles without universal applicability. In other words, the opposition between the two concepts is not designed to model the entire spectrum of Soviet cultural activity. Paperny’s idea is that changes in architecture as well as in other areas orient themselves towards a more general dynamic process, “culture”. Culture is generated not by individual subjects but by the dynamic process of culture itself that induces individuals to act upon their interests or aspirations. At one point, Paperny writes: “All developments in Soviet architecture from the end of the 1920s to the beginning of the 1930s may be viewed as an expression of more general cultural changes, the most important being the victory of Culture Two over Culture One […]. Certain processes in Russian history, specifically in the history of architecture, are cyclic and may be viewed in terms of the alteration between Culture One and Culture Two.”

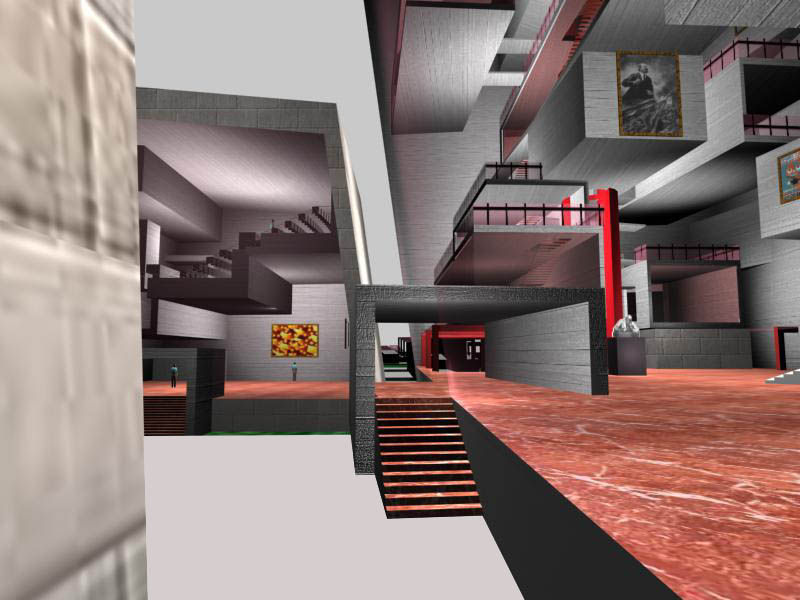

The historical avant-garde was fixated on the future to a point where it repressed all tradition, postulating that “the future is now.” As the poet Vladimir Mayakovsky put it, “I want the future today”. Culture Two views the future as infinity. Since the future is so far away, Culture Two turns its gaze to the past, finally viewing itself as the culmination of all historical development. This culmination was to have found architectural expression in the never-to-be-built Palace of the Soviets; but, since no one building could possibly do justice to the Stalinist era as the culmination of history, seven skyscrapers were built instead. Whereas the architects of Culture One thought horizontally, using plans and maps, in Culture Two, the very idea of planning is viewed as negative. Culture One is a culture of movement where houses are designed to rotate as if they were on wheels. The avant-garde aimed to de-urbanize the cities, creating a uniform space without hierarchical order where any space-the sky, the earth, the oceans-are to become habitable. Culture One cultivates a rational functionalism with an emphasis on practical values, while Culture Two has a mythological consciousness that leads to symbolic art. Culture One subscribes to architecture as a universal language that transcends national cultural boundaries. The ideas of Karl Marx are the same in Soviet Russia or in any other country. This kind of “horizontal” thinking was opposed by the more vertically oriented Culture Two with its sharp distinctions between proletarian and bourgeois, good and evil, categories that Culture Two transformed from social into spatial categories. These boundaries could not be crossed without such a crossing being noticed. In architecture, this found expression in socialist realism’s emphasis on enormous entrance areas, sometimes featuring arches up to seven stories high. (Witness also the lavish entrances to the subway stations).

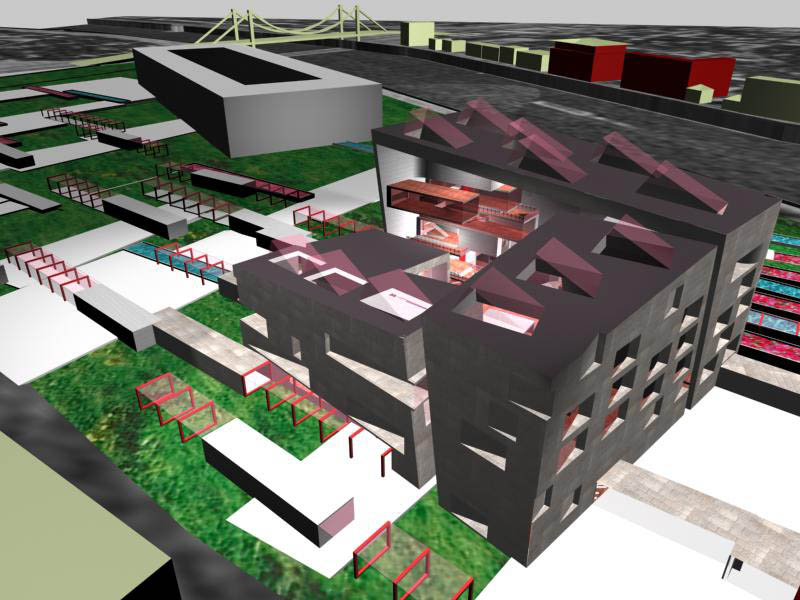

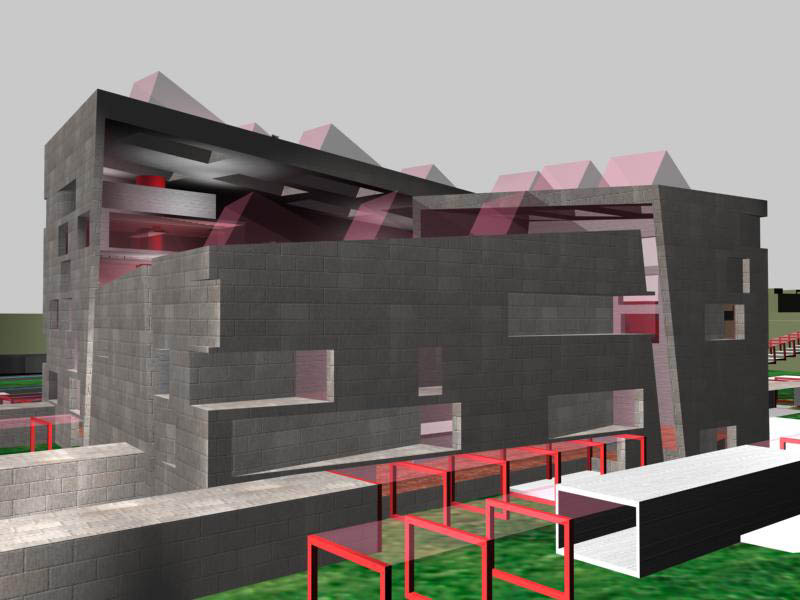

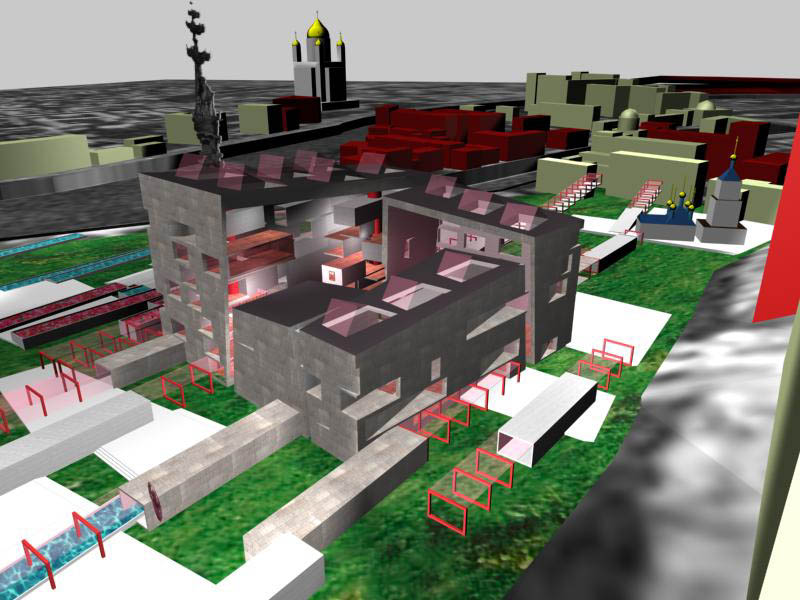

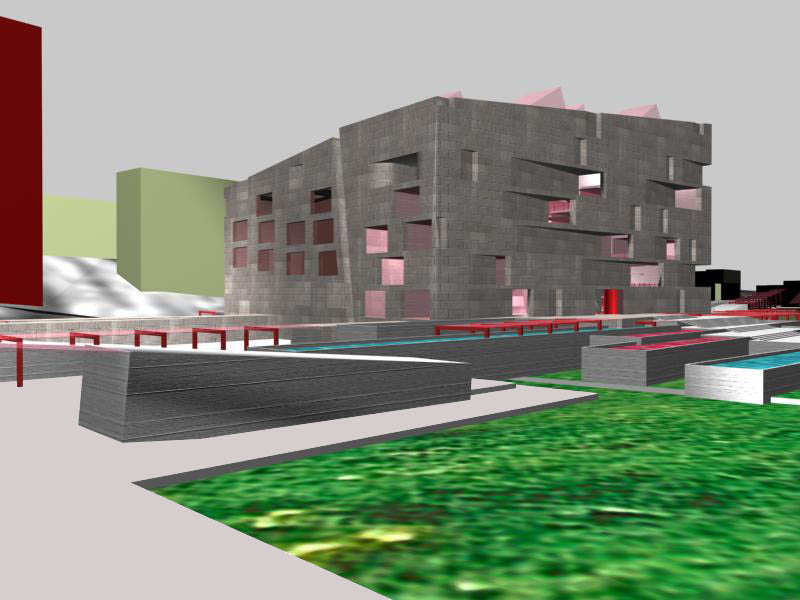

My design for The Museum of the USSR had to take account of the complexities of the struggle between Culture One and Culture Two. I felt strongly that the museum building itself had to be as important as the exhibitions it was going to hold. The only way to deal architecturally with the complexities of Soviet life without being illustrative and literal was to have the museum building visualize the struggle between Culture One and Culture Two. The Museum of the USSR visualizes the conflict between two systems: Culture One is progressive, Culture Two dominates; Culture One is movement, Culture Two is stability; Culture One is horizontal, Culture Two is “centered”; Culture One suggests the free flow of individuals in a stream that creates mass movement. It is the hope implicit in the Bolshevik revolution; Culture Two is the rock in the middle of the stream, stemming the flow and repressing everything in it. Culture Two is the USSR as a closed system, a machine with which the first system is in constant conflict. However, the stream is nevertheless not blocked by the rock, more than that: it destroys the rocks solidity by creating an open, transparent structure inside it. The stream existed already 100 years ago and is still flowing, leaving its marks on the Soviet Union that has now itself become a museum. My museum contains the traces left by the individuals that passed through it.

Description of the museum

The Museum of the USSR is located in the center of Moscow, inside the Garden Ring, within a historical ensemble of buildings. The museum is visible from the Moskva river embankments on both sides, as well as from Krymsky Bridge and from the Garden Ring. It is visually connected with the across the river; Central Gorky Park across the Garden Ring; the Kremlin; Embankment House, and October Square. The museum is accessible from the river as well as from the Garden Ring. The spot that I chose for the museum is now occupied by the Sculpture Garden, an exhibition of sculptures and monuments dedicated to Soviet party leaders and other famous Soviet people. The large garden (approximately 1,500,000 sq.ft.) provides plenty of space for the new museum.

The traces of the individuals that passed through the USSR are the gaps or holes left on the walls of The Museum of the USSR. The museum consists of a cube broken up into four galleries.A courtyard is located in between the four individual buildings. The museum’s main gallery faces the river. It is itself composed of smaller galleries, a.k.a., the pieces of the past that became part of the system, as if the individuals who were moving through its space were all of a sudden trapped inside. Culture One invades Culture Two and is now resting at its very center. The smaller galleries are stacked on top of one other along the northern and the southern walls of the main gallery, with an open space in between each gallery. The individual floors are completely separated, which leaves open the possibility of exhibiting large objects. The smaller galleries are designed to house various types of expositions. They also accommodate the cafe (top floor), a videotheque, an information room, and the cloakroom (first floor). The galleries can be accessed directly by the elevator, or they can be observed by going up or down the stairs that connect one gallery with the next.

An ongoing stream of individuals is represented by the one-story buildings that “flow” through the sculpture garden from south to north. These buildings support the day-to-day operations of the museum by providing storage space for archives, administrative offices, and artist studios. From the Garden Ring they lead the visitors to the south entry of the museum on the Moskva embankment. This entry utilizes the same sequence of one-story buildings, resembling a log damming up a flowing stream. The buildings also provide shelter for the hundreds of art dealers who crowd the embankment and the Sculpture Garden, trying to sell their goods from camping tables.

The second building (to the north) is the library. The same principles govern this space that applied to the main gallery. Once again, the fragments of Culture One (the free flow of individuals) is held captive inside, this time in the form of balconies holding bookshelves. The first floor is left open so one can feel the heavy weight of history above one’s head. On the ground level are classrooms and auditoriums that are attached to the library. These buildings are part of the flowing stream. Two more buildings complete the cube, the sports galleries to the east (sport being a very significant part of Soviet culture), and the theater (facing south). With its 200 seats, this is the smallest of the buildings that compose The Museum of the USSR.