Jugoslovenka as an Act of Resistance

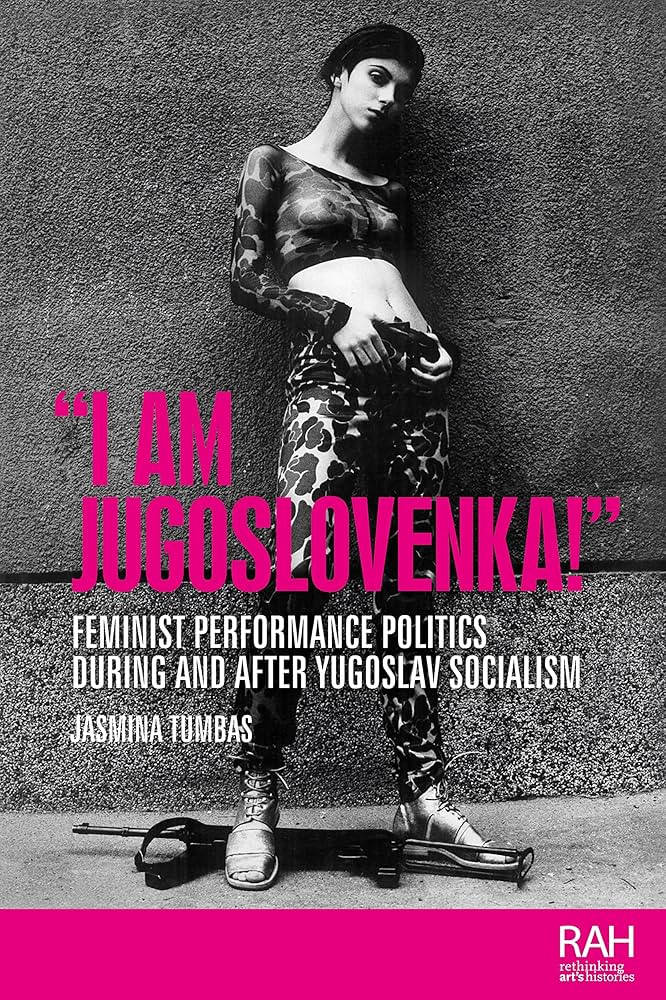

Jasmina Tumbas, I am Jugoslovenka! Feminist performance politics during and after Yugoslav Socialism (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2022), 344 pp.

Reading the first chapter of Jasmina Tumbas’ publication I am Jugoslovenka! made me smile and think of my mother. The author cites Bojana Pejić talking about wearing original Levi’s jeans. My mother grew up in socialist—explicitly not communist—Poland, and moved to the Netherlands in the 1980s, when she was in her twenties. When I bought my first pair of jeans, she told me she got her first pair from Yugoslavia, where Western commodities were so much easier to obtain. Through her stories, Yugoslavia seemed like a country of possibilities and freedom, even if it was situated on the other side of the Iron Curtain. In contrast to the other countries in the region, Yugoslavia had open borders allowing people to travel and trade outside the Iron Curtain. The country saw women and men as equals, gave them equal pay, the right to abortion, and paid maternity leave. One might almost ask: what did Yugoslav feminists possibly have to resist? A similar thought led “the male dominated Yugoslav communist elite to declare that it had reached its goal of the liberation of women and that feminism was thus obsolete.” (p. 1)

Through the figure of Jugoslovenka (Yugoslav woman), Jasmina Tumbas creates a conceptual framework to present how politics, female emancipation, and art were intertwined in Yugoslavia. Tumbas based the title of I am Jugoslovenka! on the hit song “Jugoslovenka” (1989) by the Yugoslav pop singer Lepa Brena. In the video, Brena presents an idealized version of Yugoslavia: a beautiful young blonde woman enjoying the vibrant summer running through the green mountains, the golden fields full of grain, or casually relaxing on a boat sitting next to the Yugoslav flag. Brena, as a Yugoslav symbol, represented the country’s multiculturalism, including the “primitive forces,” as Tumbas describes the local folk music influenced by the Middle East. At the same time, Brena symbolized Western values as a self-made woman, making her a personification of East and West. Tumbas chose this figure of Jugoslovenka to represent “multiple generations of women who lived under or were born during Yugoslav socialism” and are connected “through the prominence of their emancipatory performance politics within visual culture and avant-garde art, specifically 1980s pop music and underground lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer (LGBTQ) artistic practices and film, performance, and activist artworks from the 1990s to today.” (pp. 5-6)

Tumbas makes a case for feminism being historically linked to politics, starting with the partisan Yugoslav women. She states that “the fight for women’s rights is the fight against fascism.”(Jelena Petrović, Women’s Authorship in Interwar Yugoslavia: The Polities of Love and Struggle (London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2018), p. 43.) Tumbas continues this narrative after the dissolution of Yugoslavia. In five thematically arranged chapters, she touches upon the positions of many female and queer artists working with performing arts, whom she identifies as Jugoslovenkas. They were all fighting for women’s rights, but by no means were they a coherent or organized group of feminists. They were connected in the way they responded to the patriarchal society through their art and the shared focus of their works on the body.

Tumbas makes a case for feminism being historically linked to politics, starting with the partisan Yugoslav women. She states that “the fight for women’s rights is the fight against fascism.”(Jelena Petrović, Women’s Authorship in Interwar Yugoslavia: The Polities of Love and Struggle (London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2018), p. 43.) Tumbas continues this narrative after the dissolution of Yugoslavia. In five thematically arranged chapters, she touches upon the positions of many female and queer artists working with performing arts, whom she identifies as Jugoslovenkas. They were all fighting for women’s rights, but by no means were they a coherent or organized group of feminists. They were connected in the way they responded to the patriarchal society through their art and the shared focus of their works on the body.

In the first chapter, “Jugoslovenka’s Body under Patriarchal Socialism: Art and Feminist Performance Politics in Yugoslavia,” Tumbas introduces several artists and art workers, showing the broad spectrum of the Yugoslav cultural field of the time, ranging from artists to curators and museum directors. She focuses here on the “New Art Practice,” referring to a cluster of conceptual and performance artworks in 1960s-1980s Yugoslavia that mainly took place in urban areas in Serbia, Croatia and Slovenia. It would be an obvious choice to focus on well-known female Yugoslav artists like Marina Abramović and Katalin Ladik, but Tumbas decided on a different approach. Of course, these famous artists are also included in the book as they are part of this history, but so are many others.

In an attempt to give a complete overview, and certainly a more inclusive narrative, the women that Tumbas highlights in this publication operated in what could be considered high and low cultural fields. This diversity is clear in the second chapter, where Tumbas takes a closer look at three Yugoslav celebrities: performance artist Marina Abramović, pop singer Lepa Brena, and queen of Romani music Esma Redžepova. She chose these artists based on their prominence “within their field of culture: in the sphere of avant-garde visual and performance art, artist Abramović; and as performers and businesspeople in the popular music sphere, singers Brena and Redžepova. All three women were ‘firsts’ in their fields, achieving breakthroughs previously unattainable for women within the Yugoslav context.” (p. 114)

Supporting this diverse and inclusive history, Tumbas dedicates her third chapter to the queer Jugoslovenka, mainly situated in 1980s Ljubljana. The city allowed the underground scene to flourish, uniting punk, gay, and lesbian avant-garde art circles with performance art. However, members of this vibrant scene resisted the so-called equality propagated by the socialist state. Tumbas nuances this, arguing that “socialism’s complicated gender politics and general egalitarianism” created opportunities for gays and lesbians to be more visible. (p. 171) It was rather patriarchal domination that prevented the queer community from obtaining further equality.

In the fourth chapter, “Jugoslovenka in a Sea of Avant-garde Machismo: A Feminist Reading of NSK,” Tumbas substantiates her hypothesis that Ljubljana was a fruitful place for avant-garde art by examining the collective Neue Slowenische Kunst (NSK) from a feminist perspective. This group made politically radical and influential art and had a successful international career after the dissolution of Yugoslavia. Tumbas looks at the figure of Jugoslovenka in this male-centered group. Most of the female artists of the group remain unknown and only appear silent, unidentified, and naked. Tumbas presents several cases here, supported by images of the corresponding artworks, such as Anja Rupel, lead singer of the synth-pop music band Videosex, and Eda Čufer, dramaturg and the only female founder and member of NSK.

One of the male NSK-members acknowledged that Rupel was asked to be part of one of their projects because she had “all the sex appeal [they] were looking for in this song,” besides being a good singer. (p. 205) Tumbas explains that this “shows us that women in socialist countries just as in the West could often only gain recognition and ascend if deemed attractive enough, and then, only if supported by their much better-established male colleagues.” (p. 205) Even though a progressive queer scene was developing in the same area, one of the male members of NSK pointed out that they “were simply not aware we excluded women.” According to him, feminism was already very relevant in the West, but not yet introduced to everyday life in Yugoslavia. It was also seen as an import product from the West, says Tumbas.

It is interesting to mention Eda Čufer here, who is prominently discussed in this chapter. Given the important position she held as the sole female cofounder and member of this group, it is astonishing that her role remains underexposed. However, in several conversations with Tumbas, Čufer points out she never felt that—in the socialist system—girls and boys were treated differently, and that no one placed any restrictions on how she shaped her future. She enjoyed working with the male NSK members, whom she considered smart and talented. Tumbas concludes that Čufer did not have the urge to be present in the foreground of NSK. Interestingly, she interprets this as a different representation of Jugoslovenka; one that, contrary to Brena and Abramović, puts “the needs and integrity of the collective above her own.” (p. 225)

The specific situation of Yugoslavia, positioned between East and West, influenced the perceived image and position of Jugoslovenka. Throughout I am Jugoslovenka!, Tumbas shows how the appearance of Jugoslovenka has been a topic of discussion, both in the East and West. Western feminists criticized Jugoslovenkas for looking too feminine, wearing nail polish and make up, which didn’t correspond with the stereotypical image of the working socialist woman. Artists who used sexual liberation as a subject matter, such as Vlasta Delimar, divided the feminist circles both in Yugoslavia and in the West. It is interesting to read that Delimar never saw herself as a feminist—and neither did Abramović for that matter—although both of their art practices invite a feminist reading.

This perception or misconception of Jugoslovenka continued, and maybe even worsened, after the dissolution of Yugoslavia. The last chapter, “The Last Generation of Jugoslovenkas: Diverse Forms of Emancipatory Resistance and Performance Strategies,” looks at the continuation of Jugoslovenka—a valuable addition, as it reflects on the different positions of current Jugoslovenkas and the developments in the contemporary art scene since the 1990s. Here Tumbas discusses the practices of contemporary artists Lala Raščić, Tanja Ostojić, and Selma Selman, and analyzes how their work can be seen in the Jugoslovenka tradition. Tumbas’ approach, categorizing contemporary artists as Jugoslovenkas, could be seen as an act of resistance against the current nationalistic political climate.

The national wars and the dissolution of Yugoslavia divided its former population, and the feminist positions within Yugoslav society changed rapidly. Tumbas describes the collective of feminists, lesbians, and peace movements as fundamental for feminist activism against the wars. In the last chapter, she refers to the Women in Black activists who supported women of all former Yugoslav countries during the war. This kind of support quickly turned against them; they were seen as traitors and anti-nationalistic, propagating the Yugoslav idea. In this new nationalistic reality, there was no place for Jugoslovenkas as they represented the old system where equality was seen as ore important than religion or ethnicity. In this context, it would have been relevant for Tumbas to explore more about the current position of the former Jugoslovenkas, since some of them did continue their practice after the national wars. Did their art practice change? How do they relate now to the position of resistance, and do they advocate this position of resistance in the diaspora, given the current changing political climate in the West?

Besides the criticism of Jugoslovenkas in their home country, Tumbas describes the West’s scrutiny of Jugoslovenka’s appearance during the national wars. The images that were published in Western media often depicted young, well-dressed women amidst a war zone. These images prevailed over images of elderly women opposing soldiers during a protest. And it was not just images that were misleading; facts about the war also got twisted. One of the examples Tumbas gives concerns a female US lawyer who declared that “the Serbian government [manipulates] and [screens] hardcore pornographic films depicting the actual rape of Bosnian women by Serbian men on TV and in public spaces in Belgrade.” (p. 241) Feminists refuted this story as soon as it was published. Feminist and journalist Vesna Kesić wrote a sharp critique, stating this lawyer’s story would only stir up violence and revenge, which often manifests in violence against women.

I am Jugoslovenka! is enriched by numerous images of artworks by the aforementioned artists. Much like an archaeologist, Tumbas describes the works in detail, explaining the visual language and positioning them in their political context. Most of the art works depict self-assured, strong women. Tumbas narrates in detail how this art history is more complex and layered than one might think. These female artists had to navigate their way through a male-dominated art world. Some ended up taking on other positions to support their partners by becoming art historians or curators. Others became collaborative art partners, such as Marinela Koželj. Once an artist herself, Koželj became almost a prop in the performances of Raša Todosijević, her well-known husband.

Taking the figure of Jugoslovenka as a focal point is a unique and interesting approach, since the figure symbolizes many different aspects only applicable to Yugoslavia, including its distinctive position between East and West. The way this publication researches and brings together high and low culture without hierarchy, and focuses on minorities such as queer artists as well as Roma artists, makes it truly special. Tumbas makes unknown or untold stories visible, sometimes literally. One particularly fascinating example of this approach is her exploration of the sole female participant in one of Laibach’s projects. Laibach, the musical chapter of NSK, had their photographs taken at Karl Marx’s grave in Highgate Cemetery, London. Because one of their members could not be present, they asked a woman to dress like them in a button-up shirt and tie, with her hair tied back, and take on the same pose as the rest of the members. It took Tumbas weeks to find out who this woman was (the Laibach members couldn’t remember her name), only to discover that her first name Nicolle, and she was a member of an art collective in Amsterdam. (p. 205)

Since the 2010s, interest in Tumbas’ region of emphasis has grown, and more art historical research has been conducted. This is evident from the number of publications that touch on the subjects of performance art, gender, and politics within this region, but these generally have a broader approach. One could mention Performance Art in the Second Public Sphere (2018) by Katalin Cseh-Varga and Adam Czirak, Klara Kemp-Welch’s Antipolitics in Central European Art (2014) and Networking the Bloc (2018), or Amy Bryzgel’s Performance Art in Eastern Europe since 1960 (2017). In the introduction of her book, Tumbas discusses several publications on Yugoslavia, mainly focusing on the history of feminism and feminist organizing in the arts, and on performance, in the country. The exhibition and publication Gender Check: Femininity and Masculinity in the Art of Eastern Europe (2009) has clearly been of great value for I Am Jugoslovenka! According to the curator of that pioneering exhibition, Bojana Pejić, there were no publications at that time focusing on gender in socialist art.(Hedvig Turai, “Bojana Pejić on Gender and Feminism in Eastern European Art (interview),” in Katrin Kivimaa, ed., Working with Feminism: Curating and Exhibitions in Eastern Europe (Tallinn: Tallinn University Press, 2012), p. 192.) Still, Yugoslavia remains underrepresented in the Gender Check publication, a situation that I am Jugoslovenka! aims to remedy.

I am Jugoslovenka! is a much-needed addition to existing research, in which Tumbas looks critically at socialism from a feminist perspective, and at the significance of Yugoslav feminist performance politics. On this topic, the reader will also find Uroš Čvoro’s forthcoming publication Bosnian Girls: Contemporary Feminist Art in Bosnia and Herzegovina (2025) of interest. Čvoro’s book is expected to provide more insight into the contemporary developments of feminist art in the region, including the period after the wars, and might even include some of Tumbas’ Jugoslovenkas.

At the start of this review, I questioned what Yugoslav feminists could resist against. In conclusion, one might say that the female artist, Jugoslovenka, was in a constant struggle for her position. Jugoslovenkas needed to defend themselves abroad as well as at home. They were fighting a constant battle in a patriarchal system, and were often misunderstood. It was a struggle with, as Tumbas states, “Yugoslav socialism’s paradoxical relationship to gender equality: gender norms could be broken on surface level, but patriarchal power staunchly remained the operative visual regime.” (p. 206)

Coming back to Lepa Brena’s hit song “Jugoslovenka,” it is interesting to realize this song was released the same year that Slobodan Milošević became the President of Serbia. At that time, it was already clear that the Yugoslav society was crumbling under the pressure of nationalism. The song was made at a turning point, which gives the title of this publication an extra layer. In her last chapter, Tumbas discusses how the perception of Jugoslovenka in the European male imagination changed only five years after Brena’s song. She refers to a text written on one of the army barracks in Srebrenica, most probably by a Dutch soldier stationed there at the time: “No Teeth… ? A Mustache… ? Smell Like Shit… ? Bosnian Girl!”. Bosnian artist Šejla Kamerić used the text written on the army barracks for her powerful work Bosnian Girl (2003), covering her black-and-white self-portrait. It became one of the most well-known feminist artworks in the region. Seventeen years later, a collective of four Bosnian-Dutch women active in the Dutch cultural field that campaigns for an inclusive historiography and commemoration of the Srebrenica genocide in the Netherlands, took on the name of Kamerić’s work. Their Temporary Monument (2020) was exhibited in front of the Dutch Parliament. The collective presents an example of how Jugoslovenka continues to live on in the diaspora.

In a way, we can see I am Jugoslovenka! as a prelude to the research Tumbas is currently conducting on queer and feminist Yugoslavs in the diaspora. It will be interesting to see how their mentality and thoughts are influenced by their new social and political contexts—and perhaps how they advocate this position in the diaspora. Given the current changing political climate in the West, one would hope for some of Jugoslovenka’s idealistic perspective.