I Menstruate, So Should I Stay at Home?

This Month I Menstruate, Gallery Art Factory, Wenceslas Square, Prague, March 3 – March 19, 2004

Exhibiting artists: Barbora Baronova – Pavlina Binkova – Veronika Bromova – Stanislav Divis – Roman Franta – Lenka Fritschova – Adela Havelkova – Milova Havrankova – Tereza Hendlova – Veronika Hubkova – Tereza Janeckova – Peter Javorik – Lenka Klodova – Gabriela Kontra – Iveta Kratochvilova – Katerina Mala – Rita Marhaug – Stepanka Matuskova – Eva Meisnerrova – Osamu Okamura – Pipi Modra Puncocha – Jiri Pliestik – Jana Stepanova – Petra Valentova – Jirina Zachova – Jitka Zabkova

In 1972, a group of young women artists organized in a residential district of LA with an exhibition simply entitled “Womanhouse.”

This exhibition can be considered a key point for the feminist movement in the U.S. For one month, an old, abandoned house was filled with installations that commented on various aspects of women’s lives.

There could have been no better or no more authentic a place for such a project than a suburban house where many American wives were spending most of their time.

One of the works that caused the most emotional debates was the installation by Judy Chicago “Menstruation Bathroom”.

The artist painted the entire bathroom with a bright white color, and stowed piles of sanitary napkins on the shelves above the toilet and washbowl.

The only element that interfered with the whiteness of the room was a litter-basket full of bloody towels and tampons – one of them was lying, provokingly, on the floor.

Although Chicago was facing criticism that accused her of distaste, exhibitionism, and immorality, the collective project of “Womanhouse” was a dismissal of the systematic motif in women’s lives, mainly in the residential suburbs: children, kitchen, and Sunday masses (Kinder, Küche, Kirche).

In the 1970s, the American society was still marked by conservatism from the McCarthey era, and to speak publicly about intimate life was taboo.

Just a month ago, in February 2004 (more than thirty years after the Californian project), the Prague-based Gallery Art Factory opened a show called This Month I Menstruate, which was initiated by the Center for Gender Studies in Prague, and accompanied by a few lectures and film-screenings.

|  |

On the Wenceslas Square, in the middle of the city, the visitors of the gallery (and random passersby) were invited to the show by an orange banner that announced a happening of a “controversial” project.

In the Czech art scene, the theme of the show is unusual, and a straight-forward title printed on a banner attracted even those who most likely would hardly ever go to see contemporary art.

As expressed by sociologist and co-founder of the CGS, Jirina Siklova, in the morning interview on the Czech broadcasting of the BBC, one of the aims of the show was to provoke the public in thinking about issues that are rarely discussed in Czech society.

However, to declare the show as “controversial” before the opening, when it was impossible to anticipate what reactions it would cause, seemed to be misleading and calculating.

The inscription on the banner manifested more a skillful marketing strategy of the gallery than the actual content of the show – after all, who would not go to see provoking art, especially when it promises the spectacle of the most intimate folds of a woman’s body and life?

Many examples of contemporary art show that the strategy of shock, provocation, and controversy can be smartly used for promoting both artists and those whose central interest is to sell the art; one could rightly say that negative advertising is the best of all.

Certainly, there is nothing necessarily wrong about these strategies but one should keep in mind that so-called “controversial” art easily looses its critical edge when faced with the skillful promotion of gallery dealers, just because the art itself becomes a tool for miscellaneous institutional and power interests.

Let us put the complicated relationship between art and gallery business aside. It is necessary to underline, however, that challenging art marketing and artists’ promotion should remain crucial for all feminism-oriented projects. Let us then focus on the concept of the show itself.

Let us concentrate on how – and if at all – it is possible to use the strategies of the second wave of feminism at the beginning of the 21st century in an environment that is fundamentally, culturally, socially, as well as politically, different from the U.S. some thirty years ago.

Let us ask how the exhibiting artists (both women and men, even though the first group significantly predominated) dealt with the problems of social and cultural differences between genders that were claimed to be key for the show.

We should also ask, is menstruation even the right theme for challenging these, undoubtedly, burning issues at all?

The organizers from the CGS wrote in a catalogue,

[they] wanted to make easier the understanding of gender and to mediate it to the wide public. The gender issues, the politics of equal rights and other aspects were till now discussed […] only on the academic and occasionally political level. However, the social discussion openly avoids undermining social stereotypes and taboos that are embedded in the roles assigned to women and men. It is just this empty space of discussion that the exhibition wants to fill. Mainly, the show is to mediate starting and expanding the discussion on gender among people of different views, ages or social status.

If the discussion on or about gender is to the same extent about women and men –how the meaning of femininity and masculinity are formed in society and how both genders are expected to behave according to those norms – then it should be emphasized that this dimension of gender issues was totally missing from the show.

|  |

The fact that the works on display related exclusively to the women’s procreative power – be it through a direct reference to the menstrual cycle or to vaginal aesthetics – the cultural, historical and psychological meaning of men’s fertility (which, in contrast to the women’s period, was – and still is – ostentatiously paraded, and even considered as a motor of history) was omitted.

From Aristotle to Freud, the male sperm was assigned activity and thus guaranteed men’s supreme social position, while menstruation in the Western, Judeo-Christian culture, was seen as taboo, as being dirty and inappropriate.

Unfortunately, the absence of masculinity and lack of dialogue between the two sides of the gender discourse paralyzed the potential of the show to contribute to a better understanding in how gender functions and to see more critically unequal roles of men and women in Czech society. Massage salon Harmony erotic massage

As was already mentioned, there were a few men among the exhibiting artists, but not even their work pulled the show from the monotonous repetition of an iconographic “triangle” of sanitary napkin – tampon – blood.

The most interesting and challenging works were those whose authors detached themselves from literalness and descriptiveness, and conceived menstruation on a symbolic level, such Rita Marhaug.

Her series of color photographs of a pubescent girl laying in a dark-red dress on a green meadow expressed much more about both desires and pains of a growing woman’s body than, for instance, the installation of seven cotton panties (from Monday till Sunday) accompanied by seven snow-white napkins that its author, Veronika Hubkova, quite banally entitled “Where Should I Slip It?”

Among those few projects that used humor and reached the social dimension of the theme (as opposed to emphasizing the bodily/biological aspects of a period, or aestheticizing menstrual hygiene through embroidery or collages of decorative patterns) belonged a fictive pro-natal campaign by Lenka Klodova.

Her small-scale photo installation “Say NO to Menstruation!” ironically turned the key theme of the show upside down, while showing a mass of women demonstrating against the decrease of the Czech population.

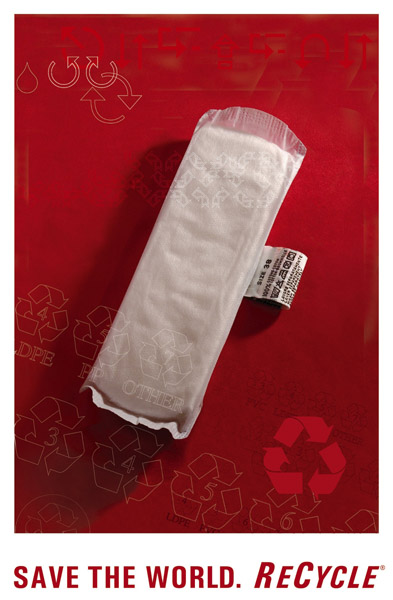

In “Save the World: Do Recycle”, a parodic video-loop and poster, Jana Stepanova and Iveta Kratochvilova launched a virtual campaign for recyclable sanitary napkins, in which they touched upon both dull TV-commercials sponsored by multinational medical and cosmetic companies with high profits and the unecological life of contemporary consumer society.

Unfortunately, there were only a very few such projects on display. While the show accentuated the physical functions and body-related hygienic proprieties (either naturalistically stained with blood, or aestheticized into “nice” compositions and patterns), it repressed the political and ideological frame of gender differences: i.e. something that Czech society, outside academic circles pays only a little attention but is actually crucial for the formation of social relations between women and men.

Celebrating the female body and female sexual desire played an important role in the development of feminist art in the U.S. thirty years ago, and one might assume that the same strategy could be similarly effective and become a turning point in Czech society that has been, until recently, very reserved and often suspicious about feminism.

However, Czech society has never been as prudish and puritan as American society, and sexuality was not considered taboo even during the worst moments of the totalitarian era; According to statistics the Czech Republic is the most secular country in Europe.

Moreover, it should not be forgotten that most surviving taboos related to intimacy and sexuality were radically challenged by women artists who entered the Czech art scene more than ten years ago, and who exposed many, until then, unthinkable parts and processes of the female body.

After seeing in various contexts closed or wide-open vaginas, pregnant bellies, embryos, lactating breasts, growing or shaved pubic hair, or lesbian and gay love, a Czech gallery goer can hardly be shocked by bodily images of any kind.

In order to sink more deeply into the critical reflection of gender stereotypes, it is necessary to search for other, less descriptive art forms, which would show female and male sexuality and gender differently than a biological given.

Certainly, the body is part of a public discourse; after all, “the private is political” became a motto for feminists fighting for women’s equality in the 1970s.

The social system we live in has an immediate impact on relations between men and women and thus even on our intimate life.

However, if one wants to unveil the complex context of these relations, one has to do more than – metaphorically speaking – to let flow gallons of blood.

Otherwise, it is difficult to get rid of an urgent feeling that the show in the GAF depicted (and maintained) women in their role of victims, and, moreover, flattened the meaning of menstruation as such.

Besides apparent and visible consequences, the monthly period also carries less tangible meanings related to cultural-historical specifications and to the social sphere.

How strongly this biological function of the woman’s body is linked to, or rather limited by, social habits was manifested in the experience of one of my female students during our class excursion to the show.

As she said quite shamelessly, she got her period just that day and when she asked the gallery co-owner if she could use the bathroom, she was recommended to go to the nearby McDonald’s.

If most exhibiting artists would have not taken the title of the show literally, and conceived menstruation not only as a problem of the “private” body but also of the “public” body, then, perhaps, the social stereotypes about women (and men as well) could have been truly undermined.

If public institutions (such as the GAF that even charges money for a visit) accommodate this little to basic human needs, then women might be forced, once again, to stop going to see art during their periods and to stay – as dirty and unwanted – at home.