Gerard Kwiatkowski: Embodying Historical Complexities in Postwar Polish “Recovered Territories”

The following text initiates “Artist Files,” a new series devoted to forgotten, understudied, or otherwise marginalized artists from the former Eastern Europe. The artists whose work we want to introduce have eluded recognition not only abroad–a fate that’s common enough for artists from the region–but also in their own countries, and for a broad variety of reasons. This essay devoted to Gerard Kwiatkowski focuses on the work of this important Polish-German artist, whose role as a curator and founder of EL Gallery often overshadowed his artistic practice.

Polish artist Gerard Jürgen Blum-Kwiatkowski is mostly known as the founder of the EL Gallery in Elbląg (1961), and as the organizer and curator of the five editions of the seminal Biennial of Spatial Forms (1965–1973), an open-air sculpture exhibition that included contributions by some of the most important Polish artists, among them Zbigniew Dłubak, Edward Krasiński, Henryk Stażewki and Magdalena Abakanowicz. Most scholars consider Kwiatkowski’s artistic practice tangential to his activities as an organizer. However, his works deserve critical attention as they mark an important attempt in Poland to combine the language of art with political and social issues. Specifically, they constitute a unique reflection in postwar Polish art history about the displacement of the German population from the former East Prussia region between 1944 and 1956, and the emergence in their place of a new Polish working class – a topic that remains politically debated and scarcely researched in Poland.(Following World War II, the region’s name was changed from East Prussia to Warmia and Masuria.) This essay highlights these issues by focusing on three works by Kwiatkowski and his initiatives from different decades: a series of early untitled matter paintings (1957–1961), the reconstruction of St. Mary’s Protestant church in Elbląg (1961–1962), and the project Multiples (1975–1976) created after the artist left Poland for Germany.

Kwiatkowski’s identity was complex from the very beginning. The artist was born as Jürgen Blum in 1930 in Faulen to a family with Polish-German roots.(J. Denisiuk, ed. Gerard Kwiatkowski/Jürgen Blum. Założyciel Galerii EL w Elblągu (Elbląg: Galeria EL, 2014), p. 9.) Prior to World War II, the town was located in former East Prussia, a German province annexed from Poland in 1773. After the war, the region was incorporated back to Poland – as part of the so-called “Recovered Territories”(The “Recovered Territories,” today more neutrally called “Western Territories,” included the regions of East Prussia (together with the city of Danzig), Warmia, Masuria and Silesia. They were pre-war German territories annexed to Poland following World War II. The great majority of the German inhabitants (an estimated 8 million) either fled or were expelled by the Polish Communist government. See T.D. Curp, A Clean Sweep?: The Politics of Ethnic Cleansing in Western Poland, 1945-1960 (Rochester: University of Rochester Press, 2006).) – and the city’s name was changed to Ulnowo. Following the defeat of Nazi Germany, the artist chose to stay in Poland, adopted the name Gerard Kwiatkowski and settled down in Elbląg.(His name appears in the Polish press in two versions: Kwiatkowski and Blum–Kwiatkowski.) Kwiatkowski’s choice was exceptional in many aspects: after the war a vast majority of the German population fled or were forced to leave the region.(A. Beevor, Berlin: The Downfall 1945 (London: Penguin Books, 2002), pp. 115–36.) The artist’s decision to remain in Poland might have been partly motivated by his leftist worldview. However, Kwiatkowski’s relationship to Communism – as this text will aim to elucidate – was also a complex one. On one hand, in the 1950s and 1960s he made a broad contribution to the social and political life of People’s Poland as a worker, activist and town councilor.(J. Denisiuk, ed. Gerard Kwiatkowski/Jürgen Blum. Założyciel Galerii EL w Elblągu, pp. 9-25.) On the other hand, he was acutely aware of the destruction wrought by the Soviets that resulted in an almost complete annihilation of German material heritage in the former East Prussia region and in the displacement of hundreds of thousands of people.

In 1953, Kwiatkowski started working at the ZAMECH factory (Polish abbreviation for Industrial Complex) in Elbląg, one of the largest and most technologically advanced industrial plants in Poland, as a decorator in charge of the design of halls and events, such as May Day.(J. Sobolewski, “Mecenas,” Dziennik Ludowy Warszawa, no. 64 15 as of March 16, 1964.) He was a self-taught artist, yet he quickly gained some recognition: his paintings were shown for the first time in 1961 at exhibitions in Toruń and Gdańsk.(”Wystawa elbląskich plastyków w Toruniu,” Głos Elbląga, no. 137 as of June 9, 1961.) It is noteworthy that from the very beginning Kwiatkowski took interest in combining the language of avant-garde art with industrial materials associated with working-class identity. This can be seen in his early work Composition from 1958: an abstract geometrical painting created using paint mixed with concrete.(J. Denisiuk, ed. Gerard Kwiatkowski/Jürgen Blum. Założyciel Galerii EL w Elblągu, p. 133.) Due to the use of mortar, after drying, the surface of the painting acquired an uncommonly rough quality. The concrete dimmed the color of the canvas, making it seem as if it was covered with a thick layer of dust.

Between 1958 and 1961, Kwiatkowski created five untitled paintings that mark his most significant attempt to combine the language of matter painting with political and social insights.(J. Denisiuk, ed. Gerard Kwiatkowski/Jürgen Blum. Założyciel Galerii EL w Elblągu, pp. 135–38. The series comprises five untitled works: four of them belong to the collection of the EL Gallery; one is in the private collection of the artist’s son.) For this series of works, Kwiatkowski used the worn-out outfits of his fellow workers from the ZAMECH factory which he cut into rectangles and then glued onto the canvas. The pieces of fabric employed by the artist still bore traces of oil, tar and other kinds of body fluids and factory grease. Artist Józef Robakowski, who participated in the fifth edition of the Biennial of Spatial Forms in Elbląg in 1973, described them as follows:

“There is also an entire cycle of “the grey ones”– grey paintings, which are sewn and then glued on the canvas. These are sharply cut-out knees of outfits of workers-painters, who painted meshes and Gerard used those knee areas to create large collage surfaces. […] I remember that series, it was very interesting because paint in those places formed layers in a very random way.” (J. Robakowski, “W Niemczech ci burmistrze to o Niego walczyli…” in: Gerard Kwiatkowski/Jürgen Blum. Założyciel Galerii EL w Elblągu, pp. 71–72.)

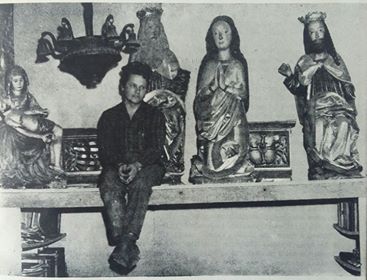

In two of the works, the canvasses were embedded in historic wooden frames that the artist most probably found in local devastated German estates.(Interview with Jarosław Denisiuk conducted on April 29, 2017. Denisiuk is the current director of EL Gallery in Elbląg and was the curator of Gerard Kwiatkowski’s exhibition Gerard Kwiatkowski. A Retrospective in 2014.) After 1945, he started to collect remnants of local dilapidated houses and estates of the German middle class and landed gentry, whose owners were forced to flee after the defeat of the Nazi army on the Eastern Front.(Interview with Jarosław Denisiuk. See also A. Beevor, Berlin: The Downfall 1945 (London: Penguin Books, 2002).) Many of their abandoned residences were first sacked by the advancing Soviet army and later nationalized by the Stalinist government in post-war Poland.(M. Jackiewicz-Garniec, Pałace i dwory dawnych Prus Wschodnich (Olsztyn: Wydawnictwo Arta, 2001), pp. 25.) At that time, Kwiatkowski became the owner of, amongst other objects, the main altar from the chapel at the Malbork Castle, which he later donated to a regional museum.(Interview with Jarosław Denisiuk.) The reasons behind the artist’s activities as a collector are difficult to reconstruct. Most probably, he was motivated both by an authentic need to rescue the material heritage of those territories and by financial reasons (he later sold several of the most valuable pieces to finance some of his art projects).(Ibid.)

In two of the works, the canvasses were embedded in historic wooden frames that the artist most probably found in local devastated German estates.(Interview with Jarosław Denisiuk conducted on April 29, 2017. Denisiuk is the current director of EL Gallery in Elbląg and was the curator of Gerard Kwiatkowski’s exhibition Gerard Kwiatkowski. A Retrospective in 2014.) After 1945, he started to collect remnants of local dilapidated houses and estates of the German middle class and landed gentry, whose owners were forced to flee after the defeat of the Nazi army on the Eastern Front.(Interview with Jarosław Denisiuk. See also A. Beevor, Berlin: The Downfall 1945 (London: Penguin Books, 2002).) Many of their abandoned residences were first sacked by the advancing Soviet army and later nationalized by the Stalinist government in post-war Poland.(M. Jackiewicz-Garniec, Pałace i dwory dawnych Prus Wschodnich (Olsztyn: Wydawnictwo Arta, 2001), pp. 25.) At that time, Kwiatkowski became the owner of, amongst other objects, the main altar from the chapel at the Malbork Castle, which he later donated to a regional museum.(Interview with Jarosław Denisiuk.) The reasons behind the artist’s activities as a collector are difficult to reconstruct. Most probably, he was motivated both by an authentic need to rescue the material heritage of those territories and by financial reasons (he later sold several of the most valuable pieces to finance some of his art projects).(Ibid.)

This juxtaposition of devastated gilded frames and worn-out workers’ outfits can be interpreted as a reflection on the sociopolitical change that occurred in former East Prussia between 1939 and 1956.(A. Leder, Prześniona rewolucja. Ćwiczenia z logiki historycznej, pp. 7-26.) After the war, the German material heritage was mostly either destroyed by the Red Army or seized by the new Polish government.(Ibid. pp. 26-48.) At the same time, a series of social and economic reforms carried out by the Communist Party ushered in an unparalleled emancipation of Polish workers and peasants in those regions. As recently noted by academic historians, the emergence of this new working class was partly made possible by the seizure of private property and its successive redistribution.(Ibid. pp. 96-150.) The new class system in post-war Poland was therefore built on the material and economic destruction of the previous one. Kwiatkowski’s matter paintings created between 1958 and 1961 reflect both those processes: the destruction of the German landed gentry and the rise in their place of a new working class.

The year 1961 marks an important moment in the artist’s biography. Following an agreement with the city council, Kwiatkowski transformed part of the ruined St. Mary’s Protestant Church from the 13th century into a contemporary art gallery. The first exhibition – a show by Kwiatkowski and Janusz Hankowski – was opened in spring 1962 and inaugurated the activity of the EL Gallery, which is still active today.(G. Kwiatkowski, “Jesteśmy optymistami,” Polska, 1965, 11/135.) The gallery, like other pioneering independent Polish art spaces opened in the late 1950s and early 1960s, such as the Krzysztofory Gallery in Cracow and the odNOWA Gallery in Poznań – enjoyed significant political freedom and support from the city council. Following its opening, the gallery organized solo shows by local artists, including Janusz Hankowski and Kiejsut Bereźnicki, as well as the consecutive editions of the Biennial of Spatial Forms between 1965 and 1973.(Centrum Sztuki Galeria EL. http://culture.pl/pl/miejsce/centrum-sztuki-galeria-el. Accessed August 25, 2017.) Especially thanks to the latter initiative, the gallery gained a fundamental role in the field of Polish art of the 1960s and early 1970s. The five editions of the Biennale mark several important turning points in Polish art history, specifically the passage from object based art (the first two editions of the Biennale, 1965 and 1976) to conceptual practices (the third, fourth and fifth editions, 1969, 1971 and 1973).(K. Dzieweczyńska, W obliczu Jubileuszu 50-lecia I Biennale Form Przestrzennych w Elblągu, (Elbląg: Galeria EL, 2015), pp. 5-35.)

The year 1961 marks an important moment in the artist’s biography. Following an agreement with the city council, Kwiatkowski transformed part of the ruined St. Mary’s Protestant Church from the 13th century into a contemporary art gallery. The first exhibition – a show by Kwiatkowski and Janusz Hankowski – was opened in spring 1962 and inaugurated the activity of the EL Gallery, which is still active today.(G. Kwiatkowski, “Jesteśmy optymistami,” Polska, 1965, 11/135.) The gallery, like other pioneering independent Polish art spaces opened in the late 1950s and early 1960s, such as the Krzysztofory Gallery in Cracow and the odNOWA Gallery in Poznań – enjoyed significant political freedom and support from the city council. Following its opening, the gallery organized solo shows by local artists, including Janusz Hankowski and Kiejsut Bereźnicki, as well as the consecutive editions of the Biennial of Spatial Forms between 1965 and 1973.(Centrum Sztuki Galeria EL. http://culture.pl/pl/miejsce/centrum-sztuki-galeria-el. Accessed August 25, 2017.) Especially thanks to the latter initiative, the gallery gained a fundamental role in the field of Polish art of the 1960s and early 1970s. The five editions of the Biennale mark several important turning points in Polish art history, specifically the passage from object based art (the first two editions of the Biennale, 1965 and 1976) to conceptual practices (the third, fourth and fifth editions, 1969, 1971 and 1973).(K. Dzieweczyńska, W obliczu Jubileuszu 50-lecia I Biennale Form Przestrzennych w Elblągu, (Elbląg: Galeria EL, 2015), pp. 5-35.)

However the importance of EL Gallery, wasn’t linked only to the exhibitions and biennales that took place there but also to the act of reconstruction itself – a fact whose symbolic meaning has been so far overlooked by Polish art historians. To fully appreciate Kwiatkowski’s efforts invested in rebuilding St. Mary’ Church, we need to note that the scale of destruction suffered by Elbląg during the war between 1939 and 1944 was indeed considerable. Extensive damage was also caused by the postwar policies of the Communist authorities: in the effort to “reclaim” the city’s Polish identity many historic German buildings were destroyed.(K. Czarnocki, Z dziejów Elbląga: praca zbiorowa, (Warsaw: Wydawnictwo Książka), pp. 23–45.) The entire Old Town was demolished and the bricks were used in the reconstruction of Warsaw.(Ibid. p. 28.) The Protestant church was left in ruins for almost two decades. Therefore, Kwiatkowski’s conservation efforts had an immense – also symbolic – meaning as an attempt to rescue the artistic culture of those territories. Indeed, the artist’s gesture can be also interpreted as a political act of defiance in the face of the government’s policy of erasing the German heritage in former East Prussia. By restoring the Protestant Church, Kwiatkowski was attempting to preserve what was left of that material culture and identity – an identity that was also his own. However, the artist never addressed those issues in any interview or text. Indeed, it would have been impossible for him to publicly and officially state his intentions in postwar Poland, a country dominated by rampant anti-German sentiments.

However the importance of EL Gallery, wasn’t linked only to the exhibitions and biennales that took place there but also to the act of reconstruction itself – a fact whose symbolic meaning has been so far overlooked by Polish art historians. To fully appreciate Kwiatkowski’s efforts invested in rebuilding St. Mary’ Church, we need to note that the scale of destruction suffered by Elbląg during the war between 1939 and 1944 was indeed considerable. Extensive damage was also caused by the postwar policies of the Communist authorities: in the effort to “reclaim” the city’s Polish identity many historic German buildings were destroyed.(K. Czarnocki, Z dziejów Elbląga: praca zbiorowa, (Warsaw: Wydawnictwo Książka), pp. 23–45.) The entire Old Town was demolished and the bricks were used in the reconstruction of Warsaw.(Ibid. p. 28.) The Protestant church was left in ruins for almost two decades. Therefore, Kwiatkowski’s conservation efforts had an immense – also symbolic – meaning as an attempt to rescue the artistic culture of those territories. Indeed, the artist’s gesture can be also interpreted as a political act of defiance in the face of the government’s policy of erasing the German heritage in former East Prussia. By restoring the Protestant Church, Kwiatkowski was attempting to preserve what was left of that material culture and identity – an identity that was also his own. However, the artist never addressed those issues in any interview or text. Indeed, it would have been impossible for him to publicly and officially state his intentions in postwar Poland, a country dominated by rampant anti-German sentiments.

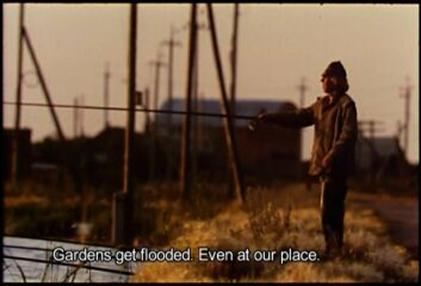

An archival film shot in 1961 by Stefan Mula, a documentary filmmaker from Elbląg who recorded many events organized by the EL Gallery between 1960 and 1980s– shows the slow and exhausting process of reconstructing the devastated church.(Stefan Mula’s film can be watched online on the web page of the Museum of Modern Art in Warsaw: http://artmuseum.pl/en/filmoteka/praca/mula-stefan-materialy-archiwalne-dotyczace-galerii-el) In one of the sequences, a team of workers is refilling the ruined walls of the church and laying new tiles on the floor. Importantly, the film also features a poster – lost today – designed by Kwiatkowski with the phrase Cześć Przodownikom Sztuki (“Glory To The Art Workers”). The poster can be considered as one of the first articulations of the concept of the “art worker” within the context of Polish postwar avant-garde art. The term was coined by Kwiatkowski as early as in 1961 when he began renovating St. Mary’s Church – a project that often required him to engage in physical manual labor. In fact, several archival photos show the artist working alongside befriended workers from the ZAMECH factory transporting concrete in a wheelbarrow and filling the brick walls of the church from a scaffolding. In the following years, Kwiatkowski will further articulate the concept of the “art worker” during the first and second Bienniale of Spatial Forms in Elbląg (1965–1967) and within the five issues of the art magazine Notatnik Robotnika Sztuki (Art Worker’s Notebook), published in 1972-1973. However, it is important to highlight that the first articulation of the concept is linked to restoration of the church in Elbląg in the early 1960s.

An archival film shot in 1961 by Stefan Mula, a documentary filmmaker from Elbląg who recorded many events organized by the EL Gallery between 1960 and 1980s– shows the slow and exhausting process of reconstructing the devastated church.(Stefan Mula’s film can be watched online on the web page of the Museum of Modern Art in Warsaw: http://artmuseum.pl/en/filmoteka/praca/mula-stefan-materialy-archiwalne-dotyczace-galerii-el) In one of the sequences, a team of workers is refilling the ruined walls of the church and laying new tiles on the floor. Importantly, the film also features a poster – lost today – designed by Kwiatkowski with the phrase Cześć Przodownikom Sztuki (“Glory To The Art Workers”). The poster can be considered as one of the first articulations of the concept of the “art worker” within the context of Polish postwar avant-garde art. The term was coined by Kwiatkowski as early as in 1961 when he began renovating St. Mary’s Church – a project that often required him to engage in physical manual labor. In fact, several archival photos show the artist working alongside befriended workers from the ZAMECH factory transporting concrete in a wheelbarrow and filling the brick walls of the church from a scaffolding. In the following years, Kwiatkowski will further articulate the concept of the “art worker” during the first and second Bienniale of Spatial Forms in Elbląg (1965–1967) and within the five issues of the art magazine Notatnik Robotnika Sztuki (Art Worker’s Notebook), published in 1972-1973. However, it is important to highlight that the first articulation of the concept is linked to restoration of the church in Elbląg in the early 1960s.

Kwiatkowski’s decision to reconstruct the church and transform it into an art space can be interpreted as a complex gesture that encapsulates multiple meanings: it was an act of rescuing the past and, at the same time, building a new space for the future. Indeed, the artist’s endeavor embodied his complex identity as a politically active art worker engaged in the development of People’s Poland and as a half-German who was confronted every day with the ruins of the German heritage in East Prussia. Interestingly, at the beginning of the 1970s, Kwiatkowski’s efforts to create this new art space were recognized by Anastazy Wiśniewski, a Polish Conceptual artist and performer with close links to the EL Gallery, as an autonomous work of art. In 1971, Wiśniewski designed a leaflet titled Gerard’s Activity. Objet d’Art, which featured photographs from the reconstruction of the former Protestant church.(Notatnik Robotnika Sztuki 1972–1973, (Elbląg: Galeria EL, 2008), p. 72.) According to Wiśniewski’s, Kwiatkowski’s activities – including those traditionally excluded from the field of art, such as mixing concrete, clearing debris and rebuilding a wooden ceiling – are actions pursued by an artist. Wiśniewski’s leaflet can be perceived as an homage to his friend; in fact, the arrangement of the photographs on the page closely resembles an altarpiece structure, both documenting and glorifying Kwiatkowski’s endeavor.

Kwiatkowski’s decision to reconstruct the church and transform it into an art space can be interpreted as a complex gesture that encapsulates multiple meanings: it was an act of rescuing the past and, at the same time, building a new space for the future. Indeed, the artist’s endeavor embodied his complex identity as a politically active art worker engaged in the development of People’s Poland and as a half-German who was confronted every day with the ruins of the German heritage in East Prussia. Interestingly, at the beginning of the 1970s, Kwiatkowski’s efforts to create this new art space were recognized by Anastazy Wiśniewski, a Polish Conceptual artist and performer with close links to the EL Gallery, as an autonomous work of art. In 1971, Wiśniewski designed a leaflet titled Gerard’s Activity. Objet d’Art, which featured photographs from the reconstruction of the former Protestant church.(Notatnik Robotnika Sztuki 1972–1973, (Elbląg: Galeria EL, 2008), p. 72.) According to Wiśniewski’s, Kwiatkowski’s activities – including those traditionally excluded from the field of art, such as mixing concrete, clearing debris and rebuilding a wooden ceiling – are actions pursued by an artist. Wiśniewski’s leaflet can be perceived as an homage to his friend; in fact, the arrangement of the photographs on the page closely resembles an altarpiece structure, both documenting and glorifying Kwiatkowski’s endeavor.

In 1974, during a visit to his family in Germany, Kwiatkowski was seriously injured in a car accident and had to undergo long-term rehabilitation.(Gerard Kwiatkowski. Niedoceniony Robotnik Sztuki. Documentary film produced by the Arton Fundation in Poland in 2017.) As a result, he decided to stay in Germany and return to the name Jurgen Blüm. His decision came as a shock to many of his friends and colleagues in Poland. However, as his close friend and art historian Lech Lechowicz explains in an interview, Kwiatkowski was increasingly conflicted with Elbląg’s authorities and felt his projects were underappreciated and not sufficiently supported.(Ibid.) The artist’s departure form Elbląg marks not only a break in his biography but also the end of the most experimental phase of EL Gallery with the last, fifth Biennale of Spatial Forms taking place in the same year.(http://www.galeria-el.pl/historia-galerii-el.html. Accessed November 19, 2017.)

In 1974, during a visit to his family in Germany, Kwiatkowski was seriously injured in a car accident and had to undergo long-term rehabilitation.(Gerard Kwiatkowski. Niedoceniony Robotnik Sztuki. Documentary film produced by the Arton Fundation in Poland in 2017.) As a result, he decided to stay in Germany and return to the name Jurgen Blüm. His decision came as a shock to many of his friends and colleagues in Poland. However, as his close friend and art historian Lech Lechowicz explains in an interview, Kwiatkowski was increasingly conflicted with Elbląg’s authorities and felt his projects were underappreciated and not sufficiently supported.(Ibid.) The artist’s departure form Elbląg marks not only a break in his biography but also the end of the most experimental phase of EL Gallery with the last, fifth Biennale of Spatial Forms taking place in the same year.(http://www.galeria-el.pl/historia-galerii-el.html. Accessed November 19, 2017.)

Some months after his rehabilitation, Kwiatkowski settled in Cornberg, a city in northeastern Germany, where he lived for the next few years, organizing several art projects for local residents and eventually creating a small art center.(J. Denisiuk, ed. Gerard Kwiatkowski/Jürgen Blum. Założyciel Galerii EL w Elblągu, pp. 17. Over the years spent in Germany, Kwiatkowski created several small art centres (he called them “art stations”) in different towns in central Germany, such as Cornberg, Fulda and Hünfeld.) In the following years, he mostly focused on curatorial activities, rarely exhibiting his new works. However, among the few pieces he created at that time was a series of works that marks his most outspoken reflection on the fate of German families after the war. Entitled Multiples (1975-76), this series consists of photographs of wealthy Germans taken before the war mounted on black panels.The photographs are fixed to the panels by spilling tar around their edges;(Ibid., pp. 154-55.) the tar’s black, thick mass seems to erase the people in the photos, symbolizing the violent onslaught of war and subsequent Communist rule. In Multiples, Kwiatkowski directly addresses the destruction of a social group with its identity, material culture and heritage. Significantly, the pieces were created after the artist moved to Germany, where such issues were easier to articulate. Although the pieces themselves are rather illustrative, they nevertheless constitute a unique attempt within Polish art to articulate the postwar experience of the German population, a topic that was seldom raised in Poland after WWII. The pieces were never shown during the artist’s life: they were exhibited for the first time – alongside many others previously unknown works – during Kwiatkowski’s first retrospective at EL Gallery in 2014.

After he left in 1974, Kwiatkowski never went back to live permanently to Poland. He remained in Germany, eventually moving to Hünfeld, where he continued his activities as an artist and organizer until his death in 2014.(Ibid.) It was only in the 2000s that he went back to Elbląg upon an invitation from the new director of the EL Gallery.(http://www.galeria-el.pl/gerard-juergen-blum-kwiatkowski-1930-2015.html. Accessed August 24, 2017.) During his stay, he donated a significant part of his art collection to the gallery and was awarded the title of “honorary citizen of Elbląg” by the municipality.

After he left in 1974, Kwiatkowski never went back to live permanently to Poland. He remained in Germany, eventually moving to Hünfeld, where he continued his activities as an artist and organizer until his death in 2014.(Ibid.) It was only in the 2000s that he went back to Elbląg upon an invitation from the new director of the EL Gallery.(http://www.galeria-el.pl/gerard-juergen-blum-kwiatkowski-1930-2015.html. Accessed August 24, 2017.) During his stay, he donated a significant part of his art collection to the gallery and was awarded the title of “honorary citizen of Elbląg” by the municipality.

Kwiatkowski’s works and initiatives reflect the artist’s complex identity split between different nationalities and postwar ideologies. Indeed, several of his projects – spanning from early matter paintings to conceptual pieces from the 1970s – encapsulate seemingly contradictory elements: an acute awareness of the past and a strong commitment to the future. Kwiatkowski realized the scale of ruination suffered by Germans in East Prussia due to the war and the Communist rule yet he decided to fully engage in the new artistic, social and political reality of People’s Poland and in the working-class ethos that it promoted. All those aspects coexist in several of his works, casting light not only on Kwiatkowski’s artistic practice but on the whole of former East Prussia’s contentious postwar history and identity. Importantly, his pieces – for decades deemed secondary to his curatorial activities and rarely exhibited – are now being to be reappraised by curators and art scholars. This process was initiated by Kwiatkowski’s first retrospective at the EL Gallery organized in 2014 – the most complete overview of his artistic practice so far. Recently, in 2016, his untitled matter paintings from the 1950s created with workers’ uniforms were included in the show Bread and Roses. Artists and the Class Divide at the Museum of Modern Art in Warsaw.(The exhibition was curated by Łukasz Ronduda and Natalia Sielewicz. An online English catalogue of the show can be found at: http://breadandroses.artmuseum.pl/.) The exhibition aimed to map class conflicts in Poland from both a historic and a contemporary perspective and Kwiatkowski’s work was included as an example of the changing class structure in post-war Poland. The show marked the first attempt to position the artist’s practice within a critical framework, in strict references to the country’s historical processes. However, as this text aimed to highlight, Kwiatkowski’s works embody multiple issues linked not only to class conflicts but also to national identities and post-war relations between Poland and Germany, making them highly relevant for further research.

Kwiatkowski’s works and initiatives reflect the artist’s complex identity split between different nationalities and postwar ideologies. Indeed, several of his projects – spanning from early matter paintings to conceptual pieces from the 1970s – encapsulate seemingly contradictory elements: an acute awareness of the past and a strong commitment to the future. Kwiatkowski realized the scale of ruination suffered by Germans in East Prussia due to the war and the Communist rule yet he decided to fully engage in the new artistic, social and political reality of People’s Poland and in the working-class ethos that it promoted. All those aspects coexist in several of his works, casting light not only on Kwiatkowski’s artistic practice but on the whole of former East Prussia’s contentious postwar history and identity. Importantly, his pieces – for decades deemed secondary to his curatorial activities and rarely exhibited – are now being to be reappraised by curators and art scholars. This process was initiated by Kwiatkowski’s first retrospective at the EL Gallery organized in 2014 – the most complete overview of his artistic practice so far. Recently, in 2016, his untitled matter paintings from the 1950s created with workers’ uniforms were included in the show Bread and Roses. Artists and the Class Divide at the Museum of Modern Art in Warsaw.(The exhibition was curated by Łukasz Ronduda and Natalia Sielewicz. An online English catalogue of the show can be found at: http://breadandroses.artmuseum.pl/.) The exhibition aimed to map class conflicts in Poland from both a historic and a contemporary perspective and Kwiatkowski’s work was included as an example of the changing class structure in post-war Poland. The show marked the first attempt to position the artist’s practice within a critical framework, in strict references to the country’s historical processes. However, as this text aimed to highlight, Kwiatkowski’s works embody multiple issues linked not only to class conflicts but also to national identities and post-war relations between Poland and Germany, making them highly relevant for further research.

Dorota Michalska is a freelance curator and art historian based in Warsaw and London. She holds a BA in Art History from the Warsaw University and an MA in Art History from The Courtauld Institute of Art in London. She was an Assistant Researcher at the Museum of Modern Art in Warsaw from 2012 to 2014. Her texts have been published in several Polish peer-reviewed art magazines. She is the recipient of the Garfield Weston Scholarship (2016) and the Young Poland Scholarship (2017).

Dorota Michalska is a freelance curator and art historian based in Warsaw and London. She holds a BA in Art History from the Warsaw University and an MA in Art History from The Courtauld Institute of Art in London. She was an Assistant Researcher at the Museum of Modern Art in Warsaw from 2012 to 2014. Her texts have been published in several Polish peer-reviewed art magazines. She is the recipient of the Garfield Weston Scholarship (2016) and the Young Poland Scholarship (2017).