Avant-Garde Book Revised by Emerging Artists at the 2024 Pavilion of Georgia in Venice

The Pavilion of Georgia at the 2024 Venice Biennial brought together three new commissions by Grigol Nodia, Nika Koplatadze, and the duo of Juliette George and Rodrigue de Ferluc, all placed in dialogue with the story of the long-forgotten German astronomer Ernst Wilhelm Tempel. On view at the Palazzo Palumbo Fossati in the San Maurizio area, this exhibition of rare daintiness and wit is a collaborative project of these emerging French and Georgian artists that revisits Tempel’s 19th-century drawings alongside 65 Maximiliana ou l’exercice illégal de l’astronomie (65 Maximiliana or the Illegal Practice of Astronomy), a 1964 artist’s book by Surrealist artist Max Ernst and modernist Georgian-born book maker Iliazd (Ilia Zdanevich) dedicated to Tempel. Entitled The Art of Seeing — States of Astronomy and curated by Julia Marchand in collaboration with Davit Koroshinadze, the show was a multidisciplinary survey stemming from the narrative and formal qualities of this exceptional example of avant-garde book art, merging images and text, and tracing their echoes in more recent practices.

The Art of Seeing echoed the title of Adriano Pedrosa’s 2024 Venice Biennial, Stranieri ovunque (“Strangers Everywhere”), with its rediscovery of lesser-known characters in the panorama of the global modernist movement. At the same time, the show was one of the rare cases at the Biennale in which a national pavilion opted for a mix of historical and contemporary artists. The team of French and Georgian artists and curators successfully created an ensemble where artists of different generations and even eras dialogued around the questions of history, oblivion, artistic media, and identity. Interestingly, all three historical characters upon whom the exhibition shed light (Iliazd, Ernst, and Tempel) were emigrants: Tempel fled from France to Italy on the outbreak of the Franco-Prussian war; Ernst fled from Europe to the United States in World War II, and Iliazd fled from the turmoil of the Russian Empire’s civil war in the early 1920s, first to Constantinople and then finally to France.

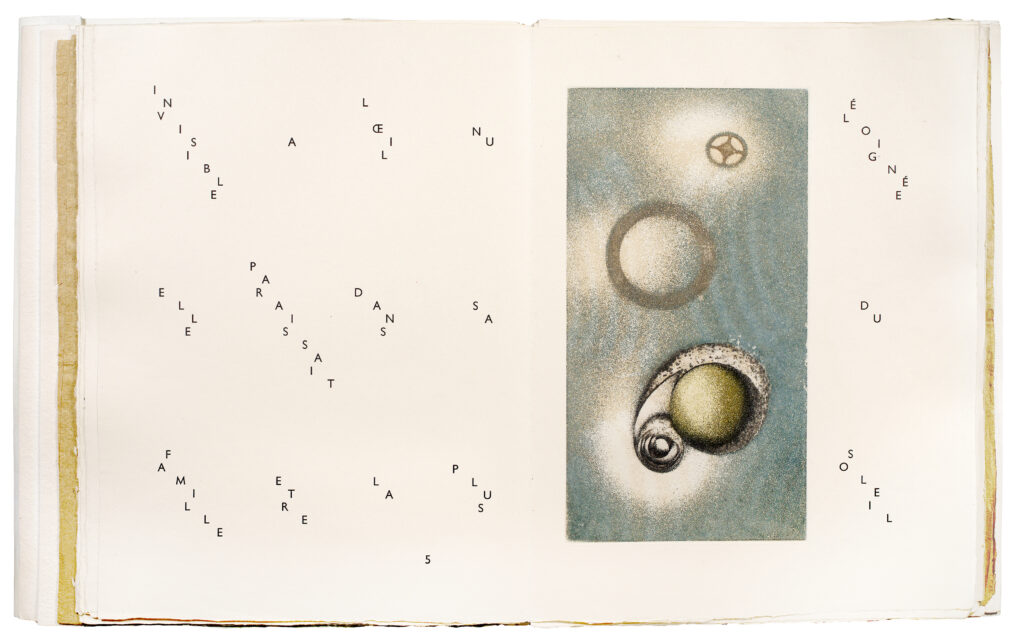

Iliazd, with Max Ernst, and Ernst Wilhelm Tempel, 65 Maximiliana or the Illegal Practice of Astronomy (65 Maximiliana ou l’exercice illégal de l’astronomie), 1964. Illustrated book with twenty-eight engravings (nine with aquatint) and six aquatints. Limited edition of 65. Courtesy of Galerie Chave. Photo credit: Michel Graniou.

The conceptual core of the exhibition was 65 Maximiliana, which poetically tells the story of Ernst Wilhelm Tempel’s discovery of a planetoid he named after the Bavarian King Maximilian II in 1861. The astronomer often abstained from the use of optical instruments, a gesture that seems utterly paradoxical from today’s perspective. In 1878, he wrote, “Memory is exercised and cultivated less than before given the mass of printed matter accumulated over the centuries and the art of seeing is being lost with the invention of all kinds of optical instruments,”(The Art of Seeing — States of Astronomy, curated by Julia Marchand, exhibition brochure, Venice 2024.) using the phrase that gave its title to both the 2024 exhibition and the Iliazd’s 1964 booklet containing a biographical essay, “L’Art de voir de Guillaume Tempel,” also illustrated by Ernst. .

Iliazd and Max Ernst were friends who had numerous interests in common. Having first met in the 1920s Parisian art milieu, they spent several holidays together, and prior to the publication of 65 Maximiliana they worked closely on it for over six months when Ernst lived in suburban Paris.(Iliazd, XX vek Il’i Zdanevicha, ed. Boris Fridman [Exhibition catalogue] (Moscow: ROST Media, 2015).) Their collaboration reflects their shared interest in language and mark making, but also in the dynamics of metamorphosis and transformation. The book combines Iliazd’s fascination with Tempel and Ernst’s interest in cosmic imageries by juxtaposing the biomorphic aquatints and enigmatical writing by the latter with Iliazd’s innovative typography . Iliazd was a highly versatile artist, whose work ranges from poetry and performance to typography, from textile design to historical and architectural research, and ultimately to epistolary and oral auto-fiction . Examples of the latter range from his early Futurist lecture-performances to the later phase, in which he recounted his earlier life, and in particular the ways he created myths about his illustrated books.(Johanna Drucker, Iliazd: A Meta-Biography of a Modernist (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2020), p. 183.) Born in Tbilisi into a middle-class family of Polish ancestry, Zdanevich, who began referring to himself as Iliazd in 1923, studied law in St. Petersburg, and in his youth witnessed and participated in the experiments of the Russian Futurists.(Research into Iliazd’s work has lately experienced a visible increase, resulting in retrospective exhibitions, scholarly papers, and most recently a biography written by Johanna Drucker, cited in the previous footnote.) Among his collaborators were many major European modernists, including Ernst, Pablo Picasso, Alberto Giacometti, and Joan Miró. Intellectually and formally rigorous, he was preoccupied with elaborating a coherent visual system that would link typography and illustrations.

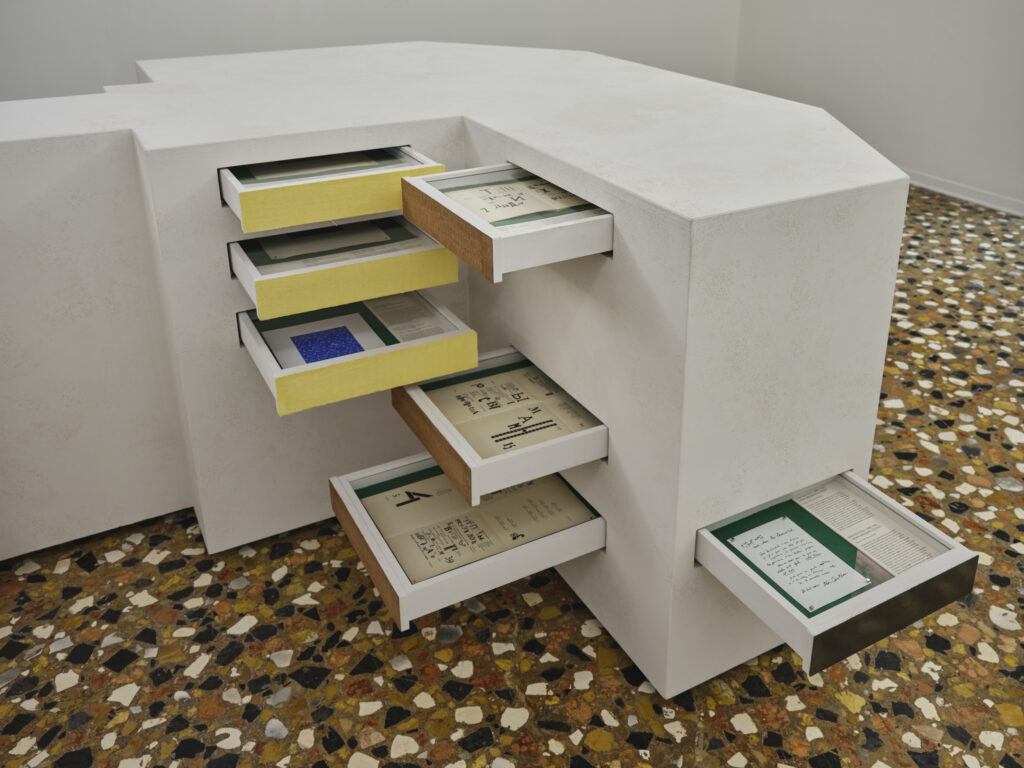

Juliette George and Rodrigue de Ferluc, Typographic furniture for archives, 2024, preparatory drawing, 21×29.7 cm. Courtesy of the artists.

A desire to rediscover unknown or long forgotten cultural figures generally distinguishes Iliazd’s activity as an intellectual, and 65 Maximiliana ou l’exercice illégal de l’astronomie highlights his deep “sympathy for the margins of culture.”(“Ilia Zdanevich (ILIAZD) (1894-1975)” [biographical entry], The Art of Seeing, exhibition brochure, n.p.) Like almost all of Iliazd’s editions, this artist book was published in a limited series, realized on precious paper, and printed manually. 65 Maximiliana’s typography challenges reading habits and transforms written language into an ornament. For example, book’s entire text is printed without punctuation marks, in a nod to aesthetic purity and the integrity of the overall composition. Archival materials from the Iliazd Archive, such as several volumes in the field of astronomy, are also displayed in the show, bearing witness to the thoroughness of Iliazd’s approach. As emphasized by the curator in her introductory text,(Ibid.) the way lettering fills the pages in Iliazd’s volume resembles the movement or even a dance of the stars, as if to parallel the constellations observed by Tempel. Iliazd’s typographic thinking, which explores the distribution of volumes and the relation between text and image, can be clearly seen in his preparatory studies, which intertwine witty word plays and Ernst’s arabesque-like visual contributions.

In the exhibition, extracts from Iliazd’s research log are laid out in a careful choreography, to allude to the book’s typography and design, which equally highlights the artistic efforts of both Ernst and Iliazd. Abstract elements of the engravings prepared by Ernst seem to be inspired by a selection of Tempel’s texts presented in three different languages. Ernst’s knowledge about 65 Maximiliana and possibly about Tempel might go back to at least the early 1930s, but most of the archival research about the astronomer for the book was done by Iliazd throughout period of over two years.

The sensory dimension of the book resonates with the interests of both artists: it echoes Iliazd’s fascination with language in his early radical poetry, and Ernst’s surrealist repertoire. Additionally, many of the lithographs in 65 Maximiliana, with constellation-like and hieroglyphic patterns, bear traces of Ernst’s innovative frottage method. As was often the case with both artists’ work, the edition is filled with symbolism, highlighting every coincidence that surrounded its conception.

65 Maximiliana recounts the story of Tempel’s discovery that he made largely in Venice. Iliazd undertook a pilgrimage to the city, and the pavilion’s curator Julia Marchand tries to connect Iliazd and Venice through both this artwork and the figure of Wilhelm Tempel. Tempel dedicated many years to night observations, but remained treated as an amateur during his lifetime—hence the subtitle of Ernst and Iliazd’s publication, “illegal exercises in astronomy”. For the curators, another essential side of Iliazd’s approach was his desire not only to narrate Tempel’s story and his talent and present it visually, but also to position his intuitions in an official scientific context.

Juliette George and Rodrigue de Ferluc, Typographic furniture for archives, 2024, preparatory drawing, 21×29.7 cm. Courtesy of the artists.

The core element of the exhibition at the Biennial was a display unit for 65 Maximiliana designed by Juliette George and Rodrigue de Ferluc, a duo of emerging artists based in France whose work is marked by their interest in the transformation of apparently practical objects, such as furniture, into interactive artworks. Juliette George’s installations, in particular, tend to aestheticize the mundane, sometimes challenging normative practices of experiencing art by incorporating elements of ergonomics and the idea of care.

In the Georgian pavilion, George and de Ferluc presented 65 Maximiliana in a very unconventional way. Iliazd rarely bound the folios of his editions and preferred to assemble them into folders or boxes, so in order to present this rare edition, George and de Ferluc developed an “archival cabinet” with numerous drawers that allowed visitors to grasp the book’s compositional dynamism, deriving from Iliazd’s editorial and poetic experiments. Thanks to George and de Ferluc’s research in the Iliazd Archive, a collection of documents originally kept by Iliazd’s widow Hélène in Paris was available to the visitors. Thus, the display of the spreads from 65 Maximiliana provided a solution to the challenge of presenting a book composed of separate folios and at the same time helps to contextualize this artwork. The twenty-four drawers of the “archival cabinet” are grouped by color, each color representing a different type of document presented. The materials collected within illustrate Iliazd’s and Ernst’s creative process, and include correspondence, private photographs, reproductions, and preparatory studies that reveal the “hidden structures” of Ilazd’s typographic compositions.

From George and de Ferluc’s display, it is possible to understand how deeply the artists—and in particular Iliazd—related to the story of Tempel and this project. Moreover, through the movement of opening the drawers, George and de Ferluc aimed to reenact the sensation of discovery that marks Iliazd’s legacy, while also echoing ideas of interactivity and modularity that were prevalent in early 20th-century exhibition design.

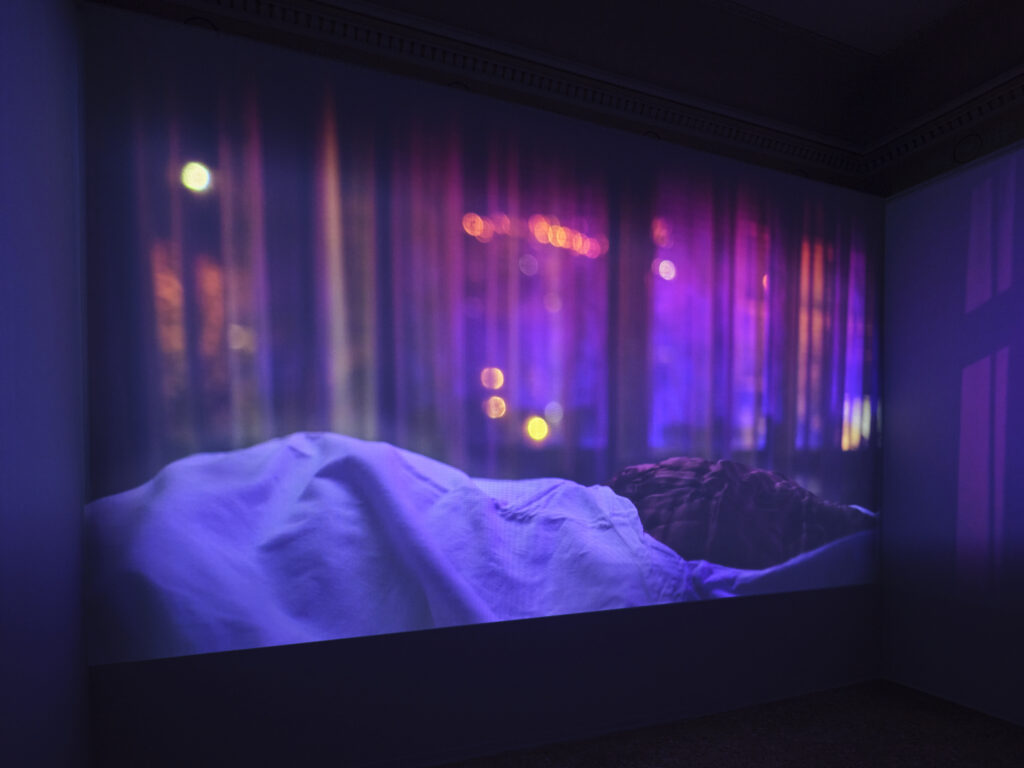

Grigol Nodia, In Between, video installation in looped projection with sound, 2024.

In the next two rooms of the pavilion, there were two interventions by Grigol Nodia and Nika Koplatadze, contemporary Georgian artists who let themselves be inspired by 65 Maximiliana. In a dark room, Nodia presented an intimate multi-channel video installation entitled In-between that explores the liminal state of sleep, taking the visitor on a journey where the visual and the tactile merge. In-between is an immersive oneiric piece that offers a space where visions fracture and are reassembled. Every time the light of the night from the outdoors crosses the room in the film, a grotesque dreamscape of shadows turns up , making phantoms emerge on the walls and the curtains.

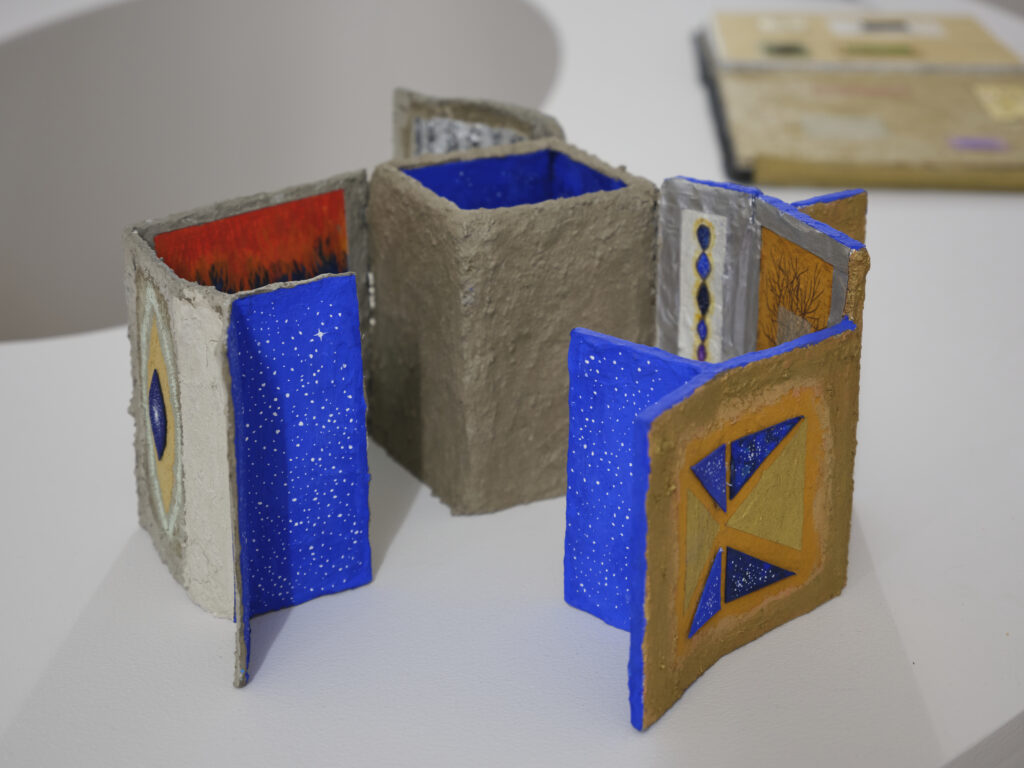

The other young artist in the exhibition was Nika Koplatadze, who responded to the commission with a sculptural investigation of book art defined by playfulness, naiveté, and lyricism. Based in Tbilisi, Koplatadze has long been exploring different cosmologies and alchemy in his practice. Since he is particularly interested in the materiality of books, Koplatadze addresses this medium as a limitless space for experiment and alternative forms of knowledge production. In the works on display in The Art of Seeing, Koplatadze explored the formalism of Iliazd’s modernist livre d’artiste by presenting three-dimensional compositions realized in aluminum foil, canvas, and cardboard together with multiple color drawings and collages using natural pigments and shimmering acrylic paint. The pedestal hosting his book-assemblages was shaped like a cosmic nebula, while multiple other astronomic forms appeared on the pages of Koplatadze’s hand-drawn works.

While Koplatadze’s pieces were directly in dialogue with 65 Maximiliana through the forms of books he chose for these sculptures, as well as the constellations most of them featured on their pages, Nodia’s installation was only ephemerally connected to Ernst’s and Iliazd’s book through the themes of night, sleep, and dreaming. Indeed, the exhibition would have benefited from a much clearer articulation of the connection between the contemporary artists and the grounds on which they interrogated 65 Maximiliana.

Nikoloz Koplatadze, Conjunction, 2021. Canvas on cement and sand background, pigment, metallic paper, metallic paint, collage 28 x 32.5 x 4.5 inches, © Nikoloz Koplatadze. Courtesy the artist. Photo credit George Shioshvili

The fourth room of Georgian pavilion was an austere space that presented a series of original drawings and studies by Wilhelm Tempel from the 1860s. These were presented on movable plexiglass supports fixed to the walls, allowing viewers to see both sides of each sheet. Documenting the paths of comets and planets’ trajectories, Temple’s papers are a testimony to his observations made with the naked eye throughout his career.

As an exploration of the world of astronomy and cosmology, The Art of Seeing connected with endeavors that absorbed many avant-garde artists of the 20th century. That fascination was complemented by the idea that the art of seeing is an art of care and attention, patience, and an eagerness to devoting one’s time to humble observation, investigating phenomena that cannot be immediately consumed. As Wilhelm Tempel said, “It is not the great telescopes that make the great astronomers.”(The Art of Seeing, exhibition brochure, p. 25.) Since mastery of the “art of seeing” might lead to something never seen before, Tempel’s gesture of giving names to his stars could be read within this exhibition as a metaphor for the very gesture of creation.

The pavilion stood out for the ways that it addressed relatively niche topics from 20th-century art history in an interactive and experimental way. Its rethinking of 65 Maximiliana through both Georgian and French artists’ interpretation of its legacy offered stimulating interpretations of this milestone editorial collaboration between Iliazd and Max Ernst. The manifold structure of the exhibition, the heterogeneous selection of artworks, and the diversity of ways in which they all related to one another might to some extent appear challenging for the audience. However, those already familiar with Iliazd’s work could find particular delight in the way his legacy was finely presented here, and how his unique book art has found a new life in the works of contemporary practitioners.

Finally, at a more conceptual level, the Georgian pavilion embraced the idea of foreigners and outsiders that triumphed at this edition of Biennale Arte. In particular, the pavilion answered Adriano Pedrosa’s call to challenge the historiography of modern art and the narratives of art history in general, rather than simply offering a social or political perspective on the theme (as several major national participations did, especially in Giardini main venue). In this sense as well, the Pavilion of Georgia represented a thoughtful exploration of the work that such historical recovery projects can really do, and the new horizons they can inspire.