Exotic Cosmopolitanism: Magdalena Abakanowicz at Tate Modern

Magdalena Abakanowicz: Every Tangle Of Thread And Rope, Tate Modern, November 17, 2022—May 21, 2023

Between autumn 2022 and spring 2023, the Blavatnik Building at Tate Modern hosted Every Tangle of Thread and Rope, a solo exhibition of textile works by Polish sculptor Magdalena Abakanowicz. Polish critic Piotr Sarzynski called the exhibition “a celebration of Polish art”—and rightfully so, as Tate’s presentation is one of the most prominent exhibitions of Abakanowicz’s work ever curated—and a unique chance for the international audience to become familiar with the sculptor and the narratives surrounding her work.(Piotr Sarzynski, “Las abakanów w Tate Modern. Wielkie święto polskiej sztuki,” Polityka, December 3, 2022, https://www.polityka.pl/tygodnikpolityka/kultura/2191086,1,las-abakanow-w-tate-modern-wielkie-swieto-polskiej-sztuki.read.) The exhibition aligned with Tate’s curatorial plan for 2020-2025, which aims to represent women artists and practices from regions less explored by the institution in their programming up to this point, including Latin America and Eastern Europe.(“Tate Vision 2020-2025,” https://www.tate.org.uk/documents/1559/tate_vision_2020_25.pdf.)

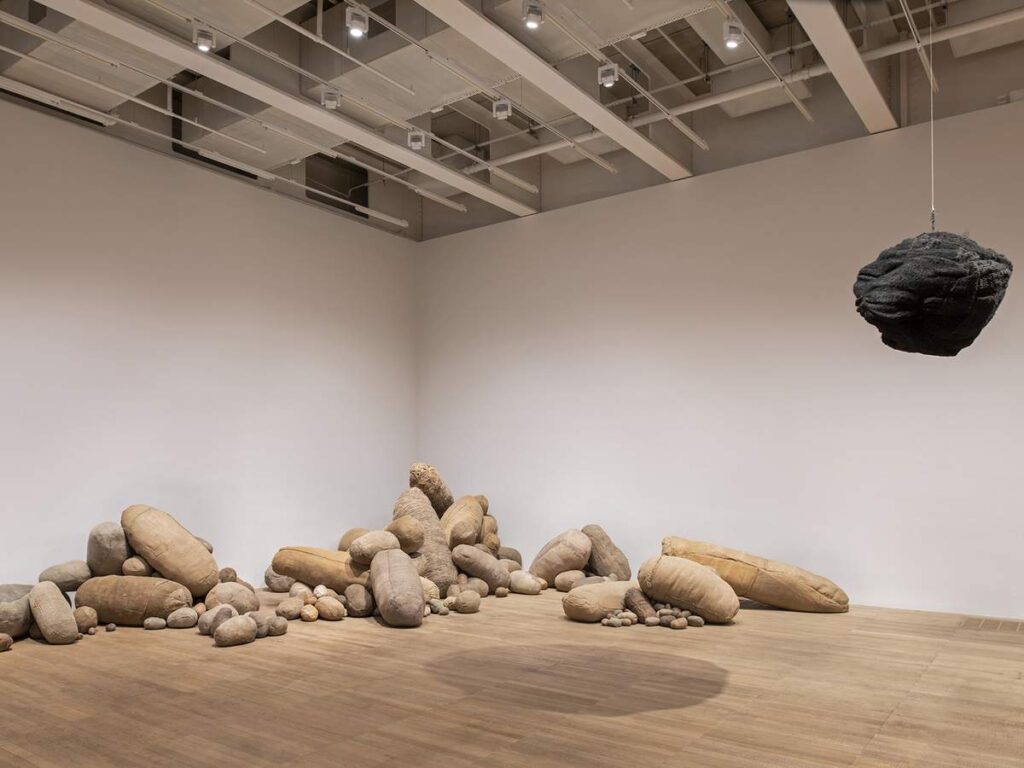

Exhibition view, Magdalena Abakanowicz: Every Tangle of Thread and Rope, 2022-2023, Tate Modern. Photo by Joe Humphrys.

The exhibition’s curators Mary Jane Jacob and Ann Coxton focused on the 1960s and 1970s, which was a transformative period for Abakanowicz’s practice, when she formulated the concept of Abakans (large-scale woven sculptures, commonly associated with the artist) and questioned the status of textiles as an unacknowledged and unrecognized medium in contemporary art discourse of the second half of the 20th century. The curators cleverly integrated Abakanowicz’s work into the contemporary discourse on environmental sustainability, by presenting the artist’s holistic relationship with nature, her creative inspirations stemming from biological processes in nature, and her usage of sustainable and ecological materials such as sisal, wool, and horsehair.

Magdalena Abakanowicz’s sculptural works developed in communist Poland gained international recognition in 1980s, due to their dynamic, visually striking, and powerful form. Her spacious woven sculptures called Abakans and her burlap figural compositions have been analyzed and discussed in contexts such as the human condition and spirituality after World War 2, representations of the body, and the relationship between humans and nature. These works have been praised due to their originality and unprecedented and unique form. Between 1950 and 2017, Abakanowicz worked with fiber, metal, and wood, and exhibited across Europe, America, and Asia. She has also been recognized as a quite controversial and ambivalent figure; as Joanna Inglot explains in her book The Figurative Sculpture of Magdalena Abakanowicz: Bodies, Environments and Myths, what made Abakanowicz controversial was her apolitical stance during the time of the communist regime, which stood in contrast to the art community around her, which was very often politically involved, striving for freedom in times of censorship and creative limitations.(Joanna Inglot, The Figurative Sculpture of Magdalena Abakanowicz: Bodies, Environments and Myths (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2004), p. 118.) Adding to this controversy is Abakanowicz’s conscious effort to control the narratives of her work, which has contributed to the limitation of the range of scholarly or curatorial readings on her art.(Inglot, The Figurative Sculpture of Magdalena Abakanowicz, p. 6.) Abakanowicz’s self-created myth, which she codified in the autobiographical essay Portrait x20, establishes the narrative of a loner, a romantic artist, free of any local, global, historical, or geographical influences. This myth was matched by a universalist interpretative narrative that she created for her work, and that relied on categories such as spirituality, mystery, powers of nature, and intuition. Inglot argues that this myth of an isolated genius from mysterious Eastern Europe helped Abakanowicz to become a recognized name beyond Polish borders.

Exhibition view, Magdalena Abakanowicz: Every Tangle of Thread and Rope, 2022-2023, Tate Modern. Photo by Marta Marsicka.

Because of Abakanowicz’s global recognition, her ambitions to sustain the tale of individual, genius artist, and the precarious position of East-Central European art globally, I was very curious about how the curators of Every Tangle of Thread and Rope would approach the artist’s work. After seeing the show, I was disappointed to find that the exhibition fortified Abakanowicz’s myth, and did very little to uncover unprecedented or fresh readings of her art.

Every Tangle of Thread and Rope followed a chronological path through the artist’s body of work, beginning with the presentation of her early paintings inspired by informel art and geometric abstraction. These rarely exhibited works from 1955–1965 feature organic animal and plant iconography that is crucial to the artist’s subsequent artistic development.

The selection of works demonstrated the transition between the flatness of rectangular canvases and irregular relief-like texture, anticipating the creation of the Abakans. Beginnings was the only exhibition room where any art-historical influences—such as Polish informel or constructivism—were mentioned in the wall texts, and similarly the only place where the wall texts addressed the historical context of post-Stalinist Poland. The wall commentary in the neighboring room, called Organic World, was fully dedicated to Abakanowicz’s inspirations stemming from environment, organic matter, and powerful natural energies. It was also accompanied by two quotes from the artist—wherein she mentions strange powers lurking in Polish forests—and the collection of exotic objects from artist’s studio, such as shells, animal horns or cocoons.

The disproportion between the very brief political and historical background given for Abakanowicz’s art, and the generous paragraphs focused on the artist’s intimate relationship with nature, along with the presentation of objects suggesting her cosmopolitan ambitions, conformed to the curatorial tendency to prioritize Abakanowicz-approved sources of inspiration, such as childhood memories and a spiritual relationship with nature. I wish the curators had approached this a bit more courageously, and critically, shedding light on rarely presented sources of inspiration for Abakanowicz’s art, such as works by Polish constructivist artists, the informel and matter painting initiated by Tadeusz Kantor, or experimental practices from Foksal Gallery in Warsaw. Those inspirations are explicitly mentioned by Magdalena Moskalewicz in a text in the exhibition catalogue, where she contextualizes Abakanowicz’s practice with the specific ground that conditioned the development of her art, namely the Polish post-war cultural landscape.(Magdalena Moskalewicz, “Knots: Abakanowicz and the Polish Art Scene in the 1960s,” in Ann Coxon and Mary Jane Jacob, eds., Magdalena Abakanowicz (London: Tate Modern, 2022).) I only wish those inspirations had been incorporated into the physical exhibition as well, for example through the presentation of archival materials.

Exhibition view, Magdalena Abakanowicz: Every Tangle of Thread and Rope, 2022-2023, Tate Modern. Photo by Marta Marsicka.

The Fibrous Forest room is spatially split between the artist’s transitional pieces, such as rope compositions, and the Abakans. Abakanowicz referred to her works with rope as situations and environments, which reflected her site-specific thinking about each piece, arranged differently depending on the space where it was exhibited. They may seem a bit visually underwhelming compared to the Abakans, but they function as an accurate curatorial choice aimed to show Abakanowicz’s conceptual understanding of the relationship between the object and the surrounding space.

Finally, the culmination of the exhibition journey was the Abakans themselves: textile sculptures suspended in a way that—thanks to impressive lighting techniques and dark-colored walls—brilliantly reflected their complex nature. They are organic, openly displaying their intricate internal spaces, sensual and personal, appearing as both textile and sculptural works. The selection of the works was striking, and it highlighted the diverse range of Abakans by presenting works ranging widely in color, shape, and textural characteristics.

Exhibition view, Magdalena Abakanowicz: Every Tangle of Thread and Rope, 2022-2023, Tate Modern. Photo by Joe Humphrys.

This room extended deeper into the gallery space, where colorful Abakans and works from the Embryology series were arranged under brighter, more neutral light. Several round egg cocoons were somewhat awkwardly placed against the wall and accompanied by curatorial commentary on the various interpretations of the works, often associated by critics and curators with female energy, the cycle of life, and fertility. In the wall text, the curators also mentioned Abakanowicz’s stern and openly declared distance from the feminist movement and feminist art. Whilst it is true that the artist took a strong stance against any gender-related readings of her art, I wish that the commentary had expanded a bit more about the context of and reasons for this distance. The history of gender politics in Eastern Bloc countries is very complex, and this declared distance from feminism was quite common amongst women artists. In her recent book Art and Women’s Emancipation in Socialist Poland: The Case of Maria Pinińska-Bereś, Agata Jakubowska explains that while it is true that there was not an organized feminist movement in communist Poland and that women artists did mistrust the Western feminist movement (probably due to the communist paradigm of gender equality), nonetheless the topics, themes, and creative strategies explored by women artists are equally important signs of women’s emancipation and self-agency. Therefore, they should be taken into consideration in studies on the expanded field of feminism.(Agata Jakubowska, Sztuka i emancypacja kobiet w socjalistycznej Polsce: Przypadek Marii Pinińskiej-Bereś (Warsaw: Wydawnictwa Uniwersytetu Warszawskiego, 2022).) As much as I understand that feminism was not the exhibition’s methodological framework, I wish more background on the topic was provided—I imagine that for an international viewer it may come across as quite bizarre that an artist who explored vaginal imagery and topics of fertility did not want to call herself a feminist, without any further contextualization.

The exhibition concluded with the wooden-metal installation Anasta 1989, and with a collection of archival materials that linearly narrated the artist’s life and the development of her practice after 1970. During these years, Abakanowicz dedicated herself to work in wood and metal, in her pursuit of becoming an internationally recognized sculptor.

Exhibition view, Magdalena Abakanowicz: Every Tangle of Thread and Rope, 2022-2023, Tate Modern. Photo by Marta Marsicka.

While the exhibition wonderfully highlighted the splendor and unique visual identity of the artist’s works, it did very little to question safe and well-established readings of Abakanowicz’s art, favoring the myth of Abakanowicz as a romantic, individualistic shaman from behind the Iron Curtain. This was particularly disappointing since the curators do explicitly recognize the necessity for a much-needed revision of Abakanowicz’s art and its meanings, as they stress in the exhibition catalogue.(Ann Coxon and Mary Jane Jacob, eds., Magdalena Abakanowicz (London: Tate Modern, 2022).) In the exhibition space, however, Abakanowicz still controls the narrative, even speaking to the audience directly, in the form of quotes sprinkled thoughout the wall texts.

I find this individualistic framing problematic in the context of the representation, curation, and reception of Polish art beyond the nation’s borders. The absence of detailed contextual background for Abakanowicz’s art within the post-war Polish art landscape suggests that there were not any local, relevant, exciting, or important visual sources for her work, which in turn feeds into the narrative of East-Central Europe as backward and creatively inferior to the West. Her practice comes across as an isolated phenomenon, which managed to rise above the grey, uninspired reality of communism.

Exhibition view, Magdalena Abakanowicz: Every Tangle of Thread and Rope, 2022-2023, Tate Modern. Photo by Marta Marsicka.

I also wish curators had tapped more directly into the ambiguity of Abakanowicz as a figure, and her practice. Why not explore the tensions inherent in the artist’s apolitical stance at a very political time in Poland? Why not expand on gender politics, feminist iconography, and Abakanowicz’s dismissal of gender’s influence on her art? Why not explore the paradox of her pursuit to become a globally recognized metal and wood sculptor, whilst it was precisely her inconspicuous textiles that ensured her international career development and ultimately established her position at the forefront of global art?

Tate’s reluctance to delve deeper into complexities between the artist’s practice, local politics, and gender was not limited to the Abakanowicz exhibition. During Every Tangle of Thread and Rope, Tate hosted exhibitions of two other women artists: Slovakian Mária Bartuszová, and Cecilia Vicuña from Chile. The temporary exhibition program thus presented the works of three women artists from three countries that have not been obvious reference points in the development of the Western contemporary art canon. However, neither themes of peripherality nor gender issues functioned as a contextual basis for the narratives presented in these three exhibitions. Tate has begun to represent women’s art from geographic peripheries, but these exhibitions do not seem to offer a platform to really develop difficult conversations about the relationship between art and power, the precarious socio-economic situations of those countries, or local struggles for gender equality.

Exhibition view, Magdalena Abakanowicz: Every Tangle of Thread and Rope, 2022-2023, Tate Modern. Photo by Joe Humphrys.

Lastly, Tate Lates—a public program that took place on February 24, 2023, accompanying Abakanowicz’s show—was disappointing not only in terms of its rather shallow exploration of themes present in Abakanowicz’s art, but also in its lack of engagement with the wide range of practicing Polish curators, scholars, and artists. The whole-day event included sculpting workshops, a Polish folk-art workshop for children, two discussions on shamanism, a panel on Polish theatre in the context of Jerzy Grotowski’s work, and a panel on Abakanowicz’s legacy in contemporary art. This panel was the only event out of six at which Polish speakers or creatives were invited to take part, with Tosia Leniarska (an independent curator), Wojciech Rusin (an audiovisual artist), and Anna Jaskiewicz (a cultural producer) participating in the discussion on Abakanowicz’s influence on their creative practices. It was discouraging to see that the public program did very little to platform Polish curatorial, educational, and artistic voices to help contextualize the public’s experience of the exhibition. This kind of contextualization was reserved for a private seminar which took place on May 12–13, 2023, where specialists on art from this region such as Agata Jakubowska, Joanna Inglot, Anna Markowska, and others were invited to share their thoughts on new perspectives on Abakanowicz’s art.

Impressive presentations of Polish art, such as Abakanowicz’s exhibition and its accompanying program, are rare opportunities to question the stereotype of the obsolete nature of East-Central European art. By showcasing contemporary Polish artists, curators, and scholars; providing an open platform for issues still not explored in Abakanowicz’s art; and highlighting the vibrant historical context behind the artist’s work, the exhibition could have been a profound step towards democratizing the discourse and history of Central and Eastern European art in the UK. Instead, Tate fortified the narrative of an individual who transcended the identity of a Polish artist to became a global one. I wonder, why cannot one be seen as both?